|

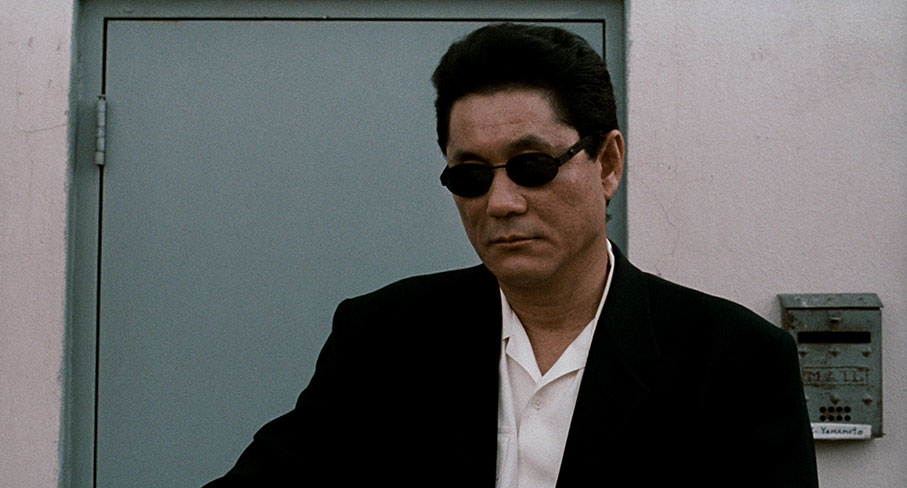

If you're a fan of the early films of Japanese manzai comic and TV personality turned filmmaker Kitano Takeshi, there's something both comfortingly familiar and simultaneously unusual about the opening images of his ninth feature, Brother. It begins with a mid-shot of Kitano himself, dressed in an open-necked shirt and dark suit jacket, his face betraying no hint of emotion and his eyes hidden behind a pair of dark sunglasses, the same image with which his masterful 1997 Hana-bi begins. It's when the film cuts to a Dutch-angled wide establishing shot that we get our first indication that we're literally in new territory here, with the distant Kitano dwarfed by an airport exterior, one whose signage the sharp eyed will realise is in English rather than the expected Japanese. The shot then smoothly straightens up, much as it would if the cameraman had suddenly realised that the tripod head had slipped and wanted to correct it as unobtrusively as possible, a visual representation of the character overcoming his initial disorientation with his surroundings perhaps. In the next shot, we're back on Kitano's icily stoic face, as he sits in the back of a taxi whose American driver is attempting conversation but getting no response, prompting him to mutter contemptuously, "The asshole doesn't even speak English." The "asshole" in question is Yamamoto, and if you know you're twentieth century history, that name may ring a bell of recognition that it turns out is relevant to the subtext of the film. In the film, however, he is primarily referred to as Aniki, despite this not being his actual given name. I'll get to the specifics of why in a minute.

Installed in his Los Angeles hotel, Aniki silently communicates with the bellboy (Alan Garcia) by giving him an overly generous tip. Half a cigarette later, he walks down to the lobby and hands the eager bellboy a piece of paper which contains an address we do not see, one the bellboy then hands to the driver of a taxi parked outside. The written destination is a sushi bar at which Aniki is under the impression that his younger half-brother Ken (Claude Maki) is working. On arriving, he is told by the Japanese American owner (Don Sato) that while Ken did indeed used to work there, he was fired after landing himself in trouble. As Aniki departs, he is approached by a young employee (Kimura Hideo), who tells him where Ken lives and warns that he is "into some bad business with some black guys." As Aniki heads towards the indicated address, he inadvertently bumps into streetwise local boy Denny (Omar Epps), a minor collision that sends the bottle of wine Denny was carrying smashing to the ground. The angry Denny confronts, insults, and tries to extort the stoically unmoved Aniki, who responds by picking up the broken wine bottle and stabbing Denny in the eye, then punching him so hard in the stomach that he collapses onto the pavement. The unflustered Aniki then resumes his journey to the run-down address to which he has been pointed and finds nobody home, so hangs around outside and looks back at the events that brought him to America in the first place.

These opening eight minutes are pure Kitano in the stripped-down minimalism both of his performance and direction. Although we can assume that he has spoken to at least one reception staff member at the hotel and asked after the whereabout of Ken at the sushi bar, none of this is shown, and we are presented instead with a taciturn character who listens but does not reply or react to the words of others. The nearest he gets to interpersonal communication is when the sushi bar employee runs out to tell him about Ken, to which Aniki offers a small nod of appreciation. This pared-down approach is mirrored in Kitano's own editing, which strips whole sequences down to the bare essentials. Thus, when Aniki visits the sushi bar, we do not see him enter, with the scene beginning after as the owner is responding to Aniki's unheard question, which is then misleadingly translated ("He quit") by the Japanese waitress (Otani Yayoi). Aniki reacts to this information by not reacting at all, standing like a statue as if waiting for a different answer until we cut to the outside of the shop after he has made his exit. His violent encounter with Denny is also handled in signature Kitano fashion: an indistinct close-up of Aniki's coat as it obscures the camera and turns the screen black; the sound of glass smashing; a static image of a broken wine bottle on the pavement; Aniki's POV of Denny as he balls Aniki out and tries to fleece him out of $200; Denny's POV as Aniki stares at him unflinchingly through his dark sunglasses then leans down to grab the broken bottle and thrust it straight into camera; Denny throwing his head back whilst holding his bleeding face in pain; a brief close-up of Aniki's twitching fist; a mid-shot as Akini punches Denny and gazes at him as he falls. Total run time, just 30 seconds.

It's in the flashback that follows that we learn a little more about Aniki's background and his true reason for leaving Japan for America. In Japan, Aniki was a high-level enforcer in a yakuza family during a time of gang warfare. When his boss is assassinated, the corrupt Police Chief (Ohtake Makoto) advises Aniki and his fellow enforcer Harada (Kitano regular Osugi Ren) to disband their family and tells them that rival yakuza boss Hisamatsu (Musaka Naomasa) has agreed to take them into his organisation if they swear new allegiance. Much to Aniki's initial fury, Harada and ten of his men agree to do so in order to protect their loved ones and help to keep the peace. When the newly inducted Harada, in a test of loyalty to his new boss, is ordered to kill the troublesome Aniki, he instead secretly offers him a way out that involves faking his death and supplying him with the forged documents he needs to quietly leave the country.

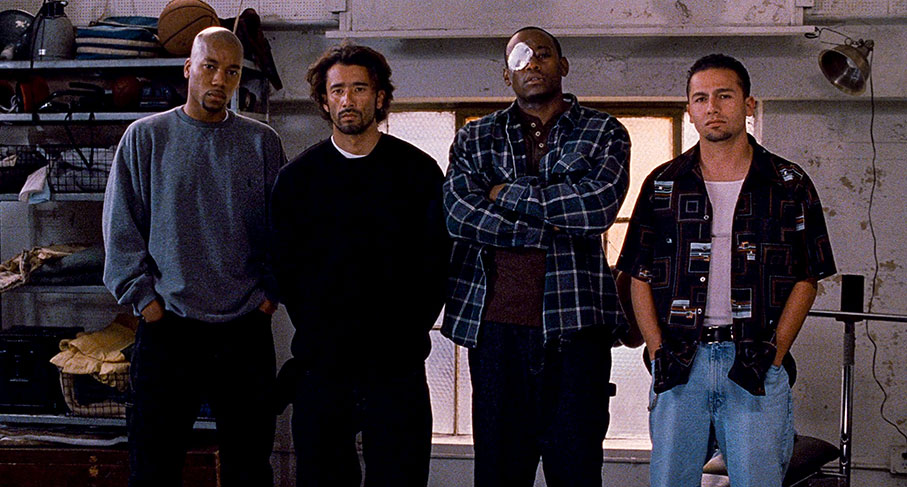

Back in the present day, Ken finally returns home accompanied by his friends and partners in crime, Jay (Royale Watkins) and Mo (Lombardo Boyar), and it's here that we first hear Aniki referred to by that name. Although originally used within families by younger siblings when addressing an older brother, it is also employed as of term of respect when speaking to a senior figure in the workplace or amongst your peers. It's the name with which Ken logically greets his older brother, and while it's safe to assume that his associates initially also refer to him as Aniki because they assume it is his name, as the story progresses it becomes an appropriate term of respect for his position and authority within their group.

After getting over his surprise at seeing his brother and nipping off to attend to some unspecified business, Ken and his companions take Aniki out to get some food, where we learn that Ken and Aniki were both abandoned as kids, that Aniki funded Ken's emigration to the USA in order for him to get an education there, and that for reasons unknown Ken ended up pushing drugs instead. At one point, Ken wonders what has happened to the as yet unspecified fourth member of their little gang, who rolls in the next day with a patch over his right eye and tells of being cut up by "some Jap motherfucker." It's Denny, of course, and as soon as he and Aniki lock eyes there's an instant moment of recognition on both of their parts. It's a key moment in the film's opening act, as while Aniki knows full well that Denny is the man that he assaulted, the fact that he is introduced as Ken's brother triggers a moment of uncertainty in Denny that allows Ken to exploit the casual racism of "we all look alike" to convince him that he has the wrong guy, despite Aniki's affirmative nods when questioned on the incident. Only later, when Aniki dons his sunglasses again, does Denny realise for sure that he was right after all.

With Denny not at full strength, his companions leave him in Aniki's company while they nip off to buy their next consignment of drugs, leaving the two men to find trivial ways to pass the time. Meanwhile, the drug buying trip hits a hiccup when hard-ass Mexican gangster Victor (Amaury Nolasco) demands far more money for the goods than Ken and his companions were expecting to pay. When Ken protests, Victor bellows angrily and slaps him, and that's when Aniki emerges from the shadows and beats Victor into bloody unconsciousness with just a couple of blows. Back at the apartment, Ken warns his brother that Rossi's men will be out to get him, and despite arming himself with one of Ken's small stash of old guns, Aniki is grabbed by Victor's men and bundled into a car for a drive that is cut short when almost instinctive swift action on Aniki's part results in the violent death of all three men. Aniki, accompanied by his three new companions, then walks calmly into Victor's headquarters, and shoots all of Victor's lieutenants dead, leaving Ken, Jay and Mo almost as startled as the wide-eyed Victor. Aniki then offers Denny $10 if he kills Victor with a single shot, and when he understandably declines, Aniki laughs and puts a bullet through Victor's forehead. Tellingly, this is the first time that Aniki has expressed real emotion since he landed on American soil.

Such is the basis for what proves to be a stylistically distinctive and culturally unusual take on a familiar story, that of a low-level criminal who moves to new territory, where, though a combination of ruthless determination and violence, he builds an ever-expanding criminal enterprise until he risks being brought down by his own hubris and/or an even greater and more dangerous opponent. Scarface, anyone? The difference here is that Aniki was already on one of the highest rungs of an organised crime family when he was forced to relocate, and he thus does not so much develop a capacity for extreme violence as bring it with him from his homeland like an amoral carry-on bag, one he opens and unleashes on a criminal community for whom such extreme action would normally be seen as a final resort. It shakes the young trio of drug dealers that he has effectively recruited to his new cause, but they quickly learn his ways, and in seemingly no time they have taken control of the entire Mexican drug operation. With an eye to expand further, they then set their sights on an alliance with Shirase (Kato Masaya), the criminal boss of the Los Angeles Little Tōkyō district, but as they continue to aggressively expand their turf, their activities bring them into conflict with an altogether different foe in the shape of the Italian Mafia.

Although techgnically an international co-production, Kitano's distinctive directorial style ensures that it always feels distinctly Japanese in pace and tone in spite of its Los Angeles location and multicultural cast. The emphasis on character ensures that it plays more like a yakuza drama than a traditional crime thriller – there are no set-piece action scenes here, just sudden, short and often bloody explosions of violence, moments of calm that are jarringly disrupted and quickly moved on from. In common with Kitano's previous yakuza films, there's also an overriding air of melancholia that you can't help think springs from the state of mind of the story's central character, a man who has lost everything he worked for and is now trying to rebuild his past with people with whom he has no natural cultural affinity. He's a stranger in what for him is a strange land, albeit one he quickly learns how to exploit for ends that he eventually starts to lose interest in, leaving the running of operations to others to spend more time with his Japanese American girlfriend Marina (Joy Nakagawa) or simply contemplate the long-term unviability of his current situation. Increasingly, there's a sense that Aniki is focussed not on profit but how he will ultimately end his days, and when the group oversteps the mark with the Mafia, Aniki tells them, "It's over. We'll all die," a statement he delivers with an amused laugh.

The links to Kitano's earlier films are evident throughout, from the self-reflective and taciturn nature of his character and the increasing sense that things will not ultimately work out well for his character, to the sharp and brutal explosions of violence and the quiet serenity of contemplative moments between. This link to his past work is further cemented by a moody score by Kitano regular Joe Hisaishi, and the casting of favourite actor Terajima Susumo as Aniki's loyal friend and yakuza comrade Kato, who follows him to America and is prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice to convince Shirase to align himself with Aniki. Perhaps the most signature Kitano moments are the light-hearted ones that focus on the between-job down time for the gangsters, as they throw a football on Kitano's beloved seashore setting or deliberately wind up the overeager Kato by refusing to pass the ball to him in a game of indoor basketball. The most telling of these scenes are the ones involving Aniki and Denny, as they act as intermittent barometers of the growing friendship between the two men, with Aniki's cheating on their gambling games initially irritating Denny but amusing the hell out of him later when they bet on the gender of pedestrians passing by the hideout in the street below. The bond between them solidifies in the film's final act, when they join forces to mentally torture Mafia boss Geppetti (John Aprea) with an elaborate but potentially deadly game that they appear to be playing solely for their own amusement, giggling like schoolkids at their actions and the effect they are having on their prey.

On its initial release, Brother had a lukewarm reception even from critics who had praised Kitano's previous work, and I kind of get why, as while the component parts are all there, as a whole the film doesn't quite click as sublimely as it has in so many of Kitano's earlier features. Perhaps it's the result of him moving out of his comfort zone and into literally alien territory, or the cuts that he later regretted having to make, but for me it lacks the poetry of Sonatine (1993), the emotional wallop of Hana-bi or A Scene at the Sea (Ano natsu, ichiban shizukana umi, 1993), or the autobiographical tenderness and wit of Kids Return (1996). The sharpness and viciousness of the violence also drew some critical flack, and there's no question that it's strong and frequently dished out here. But it's swiftly delivered and never dwelt on, and in the case of a couple of the nastiest moments – the broken chopsticks inserted into the nose of a would-be assassin and rammed into his brain is a prime example – you're convinced by the editing that you saw more than you actually did (I still wince every time I watch that sequence, however). I was also a couple of viewings in before I twigged the significance of Aniki and Ken's family name, one they share with Yamamoto Isoroku, the Japanese naval commander-in-chief during World War II and the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbour, an event whose subtextual relevance becomes clearer in the film's later stages.

I remember being initially disappointed by Brother, particularly after the sublime trio of Kids Return, Hana-bi and Kikujiro (1999), but I've found myself warming to it considerably over the years, perhaps less for how it plays as a whole than for its many fine-tooled component parts. There's an understated exploration of American racial attitudes bubbling beneath the surface, with gangs that have long been segregated along racial lines successfully challenged by one that is truly multicultural, and the friendship that develops between Aniki and Denny is blind to race and colour, being defined instead by a shared experience of childhood hardship and poverty. Kitano's decision to compress the gang's rise to power into a few key scenes does create the impression that we're watching alternate scenes from an originally longer film (according to Kitano the first rough cut ran for three and a half hours, so in a sense we are), with the result that this friendship seems to develop in sudden hops. Yet by focussing less on the scenes of confrontation and more on the moments between, this becomes a story about the bond that grows between the two main characters, as Aniki's cool stoicism and Denny's streetwise irritation both soften to move them into a convincingly shared middle ground. A tad ironically, the key turning point in this process comes when two rival gangsters are holding Aniki at gunpoint (in typically offbeat Kitano fashion, it's something we hear rather than see), and a desperate Denny opens fire on them both and accidentally wounds Aniki, who a few days later is in recovery and using the injury to make a friendly joke at Denny's expense, one that by this point Denny is also able to laugh at. It's via this unlikely friendship that the film's one-word title completes the circle of meanings that it takes on over the course of the story, ultimately demonstrating that true brotherhood is not defined by blood, by race, or even by nationality, but a sometimes accidental but meaningful meeting of minds and souls.

Brother is presented here on Blu-ray for the first time in the UK in 1080p in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, and was supplied to the BFI, and I quote, "in high definition by Channel Four," and I thus presume it's Channel Four that was ultimately responsible for the transfer we have here. On the plus side, the image is sharp with clearly defined detail, and is clean and free of damage, and in that respect is far superior to the SD transfer on the previously released and now out of print VCI/Film Four DVD. The problem, at least for this viewer, is how the picture brightness and contrast have been graded, especially when compared to the close to spot-on grade on the DVD. There's no getting around it, the image here is overly dark, with the result that it sucks picture detail into the often solidly black shadows, and even partially obscures the faces of characters in some scenes. While some might argue that this is intentional, being a visual representation of the film's noir sensibilities, I'm not buying it. We screened this film at the cinema-based film society I used to co-run, and the transfer on the previous DVD was as close as dammit to how the film looked on the big screen. Even without that comparison, however, the grading of the transfer on this Blu-ray just feels off, as the film is clearly not lit to be graded as darkly as it is on this disc. That said, there are a small number of late film daytime exterior shots that look fine here, but there are a lot of sometimes dimly lit interior scenes in this film where I struggled to see detail that is plainly visible on the DVD transfer, even when I seriously cranked up the brightness settings on my TV. It's certainly watchable but compared to the exemplary transfers on the BFI's Takeshi Kitano Collection this is a real disappointment, and all the more curious given that the film was produced by Film Four, the feature production arm of the company that supplied this very HD transfer.

Comparison frame grabs from the Film Four DVD (left) and the BFI Blu-ray (right)

The soundtrack is presented both in Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround, and the good news is that both are in excellent shape, being crystal clear and boasting a strong tonal and dynamic range that keeps dialogue audible even when quietly muttered and the gunshots loud and impactful. There is clear frontal separation on the stereo track, and pleasingly, the surround track has also been properly mixed and not just recoded in 5.1 – in one scene, gunshots fired from both behind and in front of the camera ring out from the appropriate speakers, placing us in the position of the characters in frame.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default for the Japanese dialogue, but a second optional English subtitle track for the hearing impaired that covers all dialogue and sound effects is also available.

It's worth noting that the first five special features listed here were also all on the previous Film Four DVD but have been upscaled to HD and look all the better for it. As ever, these should not be watched before seeing the film as there are a fair few spoilers contained within.

Featurette (2:16)

A short EPK in which brief interviews with a few of the actors and producer Jeremy Thomas are intercut with behind-the-scenes footage. Think of this as a taster for the special features detailed below.

Cast and Crew Interviews (15:05)

A collection of interviews with director/actor Kitano Takeshi, producers Masayuki Mori and Jeremy Thomas, and actor Omar Epps, the last of which at least was clearly shot for the Scenes by the Sea documentary. Kitano talks about the origin of the story, the decision to shoot in Los Angeles, his on-screen character, his surprise at the efficiency of the American crew, his economical filmmaking style, and the recurring role played by the seashore in his films. Masayuki explains why the film took five years to get off the ground and ponders on the possibility of working outside of Japan again, while Thomas recalls first meeting Kitano at the London Film Festival, and reflects on his quick and busy approach to directing and the importance of reaching a wider audience with this film. Epps, in what looks like a break from shooting, outlines what attracted him to the project and what he has learned from watching Kitano at work, picks his favourite scene, and equates the experience of Kitano's swift working style and minimal takes to acting for the stage.

Behind the Scenes Footage (4:01)

A (too) brief but still most welcome collection of behind-the-scenes footage of the shoot of Brother, valuable for the glimpse it offers of Kitano the director at work, framed 4:3 and shot on DV video.

Original Theatrical Trailer (1:54)

A snappily assembled and seductive American trailer that plays on Kitano's reputation as a director and showcases the film's more violent elements. Technically, there are a couple of spoilers here, but their relevance to the story is effectively disguised by the brisk pace of the editing.

Scenes by the Sea: The Life and Cinema of 'Beat' Takeshi Kitano (48:46)

Made in 2000 and first broadcast on Channel Four, this documentary by director Louis Heaton was filmed primarily on location with the production of Brother but expands beyond being a documentary on the making of the film to explore the life and cinema of Kitano Takeshi. Japanese voices are dubbed over in English rather than subtitled, a practice I'll admit to not being at all fond off, but that small gripe aside, this is an excellent introduction to Kitano and his body of work in a variety of media, from his early manzai comedy and TV shows to his unexpected move into dramatic roles, and his promotion to director on Violent Cop (Sono otoko, kyōbō ni tsuki, 1989), which kicked off a stage of his career that peaked with the international critical and festival success of his 1997 Hana-bi. Narrated by Bernard Hill, the documentary features interviews with Kitano, Brother producers Mori Masayuki and Jeremy Thomas, actors Omar Epps and Tatyana Ali, Kitano's regular score composer Hisaishi Joe, Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence director Oshima Nagisa and the film's lead actor Tom Conti, executive producer on Violent Cop Okuyama Kazayoshi, film critic John Powers, and author of The Encyclopaedia of Japanese Pop Culture Mark Schilling (whom I swear Mark Ruffalo would play in a movie based on his life). Art critic Fujiwara Erimi is even on hand to comment on Kitano's paintings. It's a busy and comprehensive portrait of the director blended with an always interesting peak behind the scenes of the production of Brother. While there may be no surprises here for long-standing admirers of Kitano's work, it's still most entertainingly presented, and if you're relatively new to his filmography and know little about the man and his extraordinary career, you should consider this essential viewing.

The Green Flash (25:25)

A short film from 1988 by writer Bob Gaydos and first-time director Adam Davis that marked the film debut of a then fourteen-year-old Omar Epps, who shines here as a young runaway named Charlie, who lives under the pier at Coney Island and gets by however he can. On the boardwalk above are small-time New York gangsters Ben (Pete Onorati) and Joey (Tony Caso), who are looking to make a drug deal with a nameless supplier (Jeffrey Bingham), despite Ben's reservations about this new direction in their criminal dealings. When the deal goes bad, a seriously wounded Ben takes refuge under the pier, where an initially frosty exchange with Charlie begins to mellow when Ben is forced to ask for his help and Charlie starts to realise how much trouble Ben is in. A simple tale, but rather eloquently told, and while this may have been the result of restrictions in budget, there's a link to Kitano's cinema in the decision not to show the gunfight that leaves Ben injured, only its build-up and its aftermath. This was shot on film, but if the scan lines on the credits are anything to go by, the print here was sourced from a video copy, and the image is a tad soft and a little glum looking, but this is a valuable and welcome inclusion, nonetheless.

Booklet

Leading the way in this 34-page booklet is an excellent essay by Jennifer Coates, professor of Japanese studies at the School of East Asian Studies in the University of Sheffield, who reveals the origin of the term 'yakuza' and traces the rise in popularity of the yakuza film in Japan, before turning her attention to Brother and the character of Aniki. She also explores the post-war American audience interest in Japan and how Hollywood responded in the 'Cool Japan' era, and how Kitano's film attempted to reset the narrative tropes of the resulting films. Up next is an enthralling and perceptive deconstruction of the characters, structure and themes of Brother, one that acknowledges the validity of the lukewarm initial response to the film before diving into why there is far more going on beneath the surface than initial impressions might suggest. The third essay, by James-Masaki Ryan, a Japan-based film critic for Rewind DVDCompare, explores the importance of brotherhood in Kitano's life and career, which proves a fascinating read that, despite my long-standing love of Kitano's cinema, I learned a surprising amount from. This is followed by a reprint of a conversation between Kitano and eastern cinema guru Tony Rayns from the April 2001 issue of Sight and Sound. Unsurprisingly, Rayns asks the sort of questions that prompt revealing answers, which include discussion of a scene in Brother that Kitano opted not to shoot because he wasn't sure how it would go down with the American cast and crew, the fact that the first cut was three and a half hours long, confirmation of the Pearl Harbour parallels, and more. The full credits for Brother (except the running time) are spread over four busy pages, after which we have credits for the special features, which include a hugely welcome and informative piece on The Green Flash by its director, Adam Davis. What I said at the start of this section about steering clear of the special features until after you've seen the film at least once also applies to this booklet, as there's a photo used to illustrate the James-Masaki Ryan essay that I'd consider a massive spoiler for newcomers.

While I still don't regard Brother as one of Kitano's finest achievements (then again, the bar is insanely high), I have grown to really appreciate it over the years, albeit more for its signature directorial elements and the effectiveness of individual scenes than as a whole, although the more times I watch it, the more I come to appreciate what Kitano was aiming to achieve. As for the disc, well, this is where I let out a small sigh, as despite the excellence of both the imported and new special features, the grading of the image makes it hard for me to enthusiastically recommend it. Kitano fans should probably get their hands on it anyway, and the inclusion of The Green Flash is a major bonus.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review except where they have adopted a western given name.

|