|

For something like the first 20 years or so of my life – or at least the ones in which I became aware of the pleasures of cinema – I associated the title The Cat at the Canary exclusively with Bob Hope and Paulette Godard. That 1939 feature, helmed by director Elliot Nugent, was one of the first films that made a serious impression on me as a kid, scaring me silly but making me laugh in equal measure. It was only later, when I started researching the genre I subsequently fell in love with, that I became aware that it was a remake of a 1927 silent feature, the first adaptation of the successful stage play of the same name by John Willard. Back in the pre-internet days, actually seeing the 1927 film was no easy feat, and much to my shame, in the years that followed I just never got around to hunting it out, so all hail Eureka for releasing it on Blu-ray in a new restoration and with some spanking special features. So viewed retrospectively, does it sit in the shadow of the beloved remake, or does it hold its own as a stylish and witty original?

Given that both films are adaptations of the same source material, the basic setup and key narrative beats in Leni’s film are unsurprisingly close to those in Nugent’s remake. As millionaire Cyrus West is on his deathbed in his reclusive castle mansion, he is all-too aware that the members of his avaricious family are itching to get their hands on his wealth when he dies, gathering round him “like cats around a canary” and driving him to the brink of madness. He responds by drawing up a will that he stipulates cannot be read until the twentieth anniversary of his death and has the document secured in a safe until then by his trusted lawyer, Roger Crosby (Tully Marshall). 20 years later, as the night of the will-reading draws in, the safe is opened by an unidentified and bestial hand, and a second envelope is added – supposedly also from Cyrus West – with the instruction that it should never be opened unless the conditions contained within the will in the first envelope are not met. When Crosby arrives and opens the safe, however, the discovery of a live moth inside it alerts him to the fact that it was opened recently by an unknown other. That’s a really nice touch. As it happens, there are a lot of nice touches in the opening scenes, but I’ll get to those in a minute.

The caretaker of the house, a cheerless woman with the iffy name of Mammy Pleasant (Martha Mattox),* pleads ignorance, despite the fact that we also saw her trying to open the safe just before Crosby’s arrival. No-one has been in this house for 20 years, she assures the lawyer, except for her and the ghost of Cyrus West. The first of the invited family members soon start arriving, and it’s clear that there’s no love lost between West’s nephews Harry Blythe (Arthur Edmund Carewe) and Charlie Wilder (Forrest Stanley), with Harry coming across as sinister and surly and Charlie as more personable and seemingly more willing to bury whatever hatchet has cleaved such a resentful gap between them. The prissy Aunt Susan (Flora Finch) and her niece Cecily Young (Gertrude Astor) get a taste of scares to come when their cab driver (an uncredited Billy Engle) refuses to take them right up to the house because he’s scared of ghosts, and the building’s gloomy gothic interior does little to calm their nerves. Perennially nervous nephew Paul Jones (Creighton Hale) has elected to drive to the house himself, but screeches to a sudden halt just outside to avoid running over film history’s most inanimate black cat. When one of the rear tyres on his vehicle unexpectedly bursts, he mistakes the resulting bang for a gunshot, a story of perceived peril that he repeatedly attempts to trade on once inside. Last to appear is Cyrus’s beautiful niece Annabelle West (Laura La Plante), a childhood friend of Paul’s whom he is obviously a little sweet on, which sets up a potential romance for later. Best to ignore the fact that they are cousins for now.

In accordance with Cyrus’s instructions, the will is read by Crosby at midnight, and while everyone present seems hopeful that they will be a beneficiary, the entire estate is bequeathed to a genuinely surprised Annabelle as the only family member with the surname West. The others react with a mixture of congratulation, disappointment and annoyance, but Crosby then reveals that the inheritance comes with a condition. He informs Annabelle that the beneficiary must be examined by the physician named in the will in order to establish his or her sanity, and if they are judged to be mentally unfit, the estate will go instead to a family member named in the second envelope that Crosby now has in his pocket. No problem there, as Annabelle is clearly in full command of her faculties, despite the bitchy Aunt Susan’s claim to Cicely that she’s probably as crazy as her uncle. This all changes when Crosby has a private chat with Annabelle in the library and warns her that the person who is named in the second envelope is aware of its contents and thus may plan to do her harm. Just as he’s about to reveal the name of this understudy heir, a secret door behind a bookcase opens and a monstrous hand drags him into the dark passage behind it. This goes unseen by Annabelle, who understandably freaks out when she turns around and discovers that Crosby has mysteriously vanished. The others come running, but are soon starting to wonder if maybe, just maybe, Annabelle might be starting to lose her marbles after all.

Those with a fondness for the 1949 remake will be comforted to see that many of the later film’s key features and plot points are also present here, and presumably had their origins in John Willard’s play. Thus, immediately after the will has been read, Mammy hands an envelope to Annabelle from Cyrus to be opened in her room, one that the others speculate could reveal the location of the famous West diamonds. In common with Wally Campbell in the remake, Paul pledges to be there for Annabelle if she needs him, but when a bad omen – here when a portrait of Cyrus falls from the wall – prompts Mammy to predict that something awful will happen, he immediately starts making excuses to leave. Things are then further complicated when a guard (George Siegmann) from a nearby asylum shows up to warn the family that a madman has escaped and is believed to be either in the grounds or the house itself. And the sequence that so terrified me as a kid, where a bestial hand emerges from a secret panel in the headboard of the bed on which Annabelle is sleeping and slowly reaches down towards her neck, is even creepier here than in the later film.

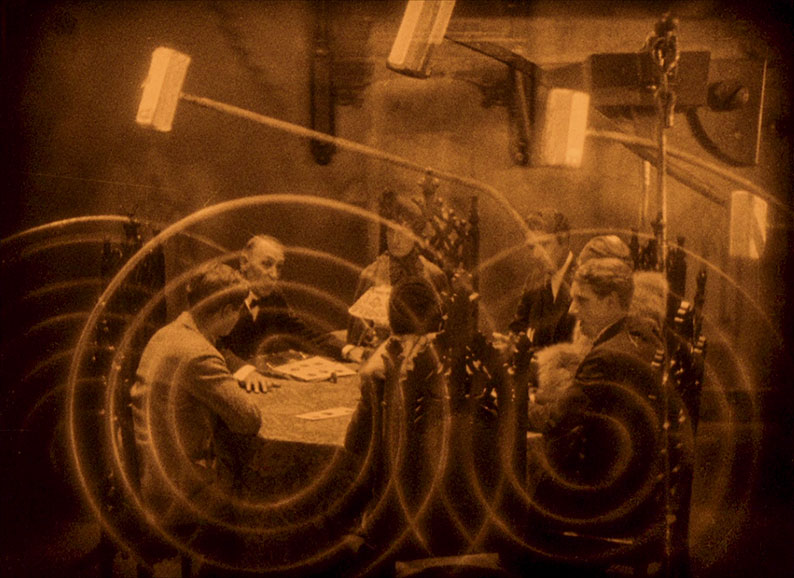

The foundations were clearly all laid in Willard’s smartly structured play, but in his first American film, German director Paul Leni – he of Waxworks (Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, 1924) and The Man Who Laughs (1928) – brings an expressionistic flare to this adaptation that transforms it from a filmed stage production into a vibrant cinematic experience. Leni’s expressionistic experimentation is on show from the opening scene, as the gothic exterior of West’s castle home dissolves into a similarly shaped arrangement of medicine bottles, seemingly imprisoned in which is the comparatively tiny figure of the dying Cyrus, who is then surrounded by towering black cats, a visual representation of the title and a complex piece of optical image layering for its day. But Leni is just getting started here. As the hour of the will reading approaches, shots of the family gathering around the table are overlaid with the interior workings of the clock chiming midnight, and as the will is read, the camera glides steadily towards Crosby’s face and right up to a massive close-up of his misaligned teeth. Elsewhere, Leni and his cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton move the camera with a purpose that feels positively modern, drifting down a corridor as curtains billow in an eerie suggestion of invisible ghosts, and disguising the identity of the villain by shooting his approach to the safe with a handheld camera from his point-of-view. Occasionally, the sheer speed of a dolly shot will take you by surprise, as when the camera races up to Crosby as he examines the second will, and later flies into Annabelle’s mouth as she screams for help.

This expressionistic creativity extends to Walter Anthony’s animated intertitles, which shiver with terror when the words “GHOSTS!” or “HELP!” are fearfully spoken, and slide down the screen a word at a time as Aunt Susan nervously says to Cecile, “Gosh what a spooky house!” But my favourite occurs during a scene in which the film moves briefly into the realms of screwball comedy, where Paul finds himself hiding under the bed that a frightened Aunt Susan and Cecily have elected to share for the night. As they casually undress, an embarrassed Paul is unable to move because his trousers are caught on a wayward bedspring. Quaintly amusing and even a little risqué for its day, it’s when Paul is discovered that things get really interesting, being seen first by a startled Susan only as a bright pair of eyes in a pool of darkness, then fully visible to a seemingly delighted Cecile. When Paul awkwardly emerges, a furious Susan lets rip with what the explosion of animated characters and shapes of the intertitle suggests was a seriously sweary outburst.

All of which might seem like I’m making a case for The Cat and the Canary purely on the basis of its adventurous use of cinematic trickery, which would be doing the film a serious disservice, as while Leni may be using every weapon in his filmmaking armoury, it’s always in service of the narrative and characters. Repeatedly his camera placement is used to enhance the storytelling, as when Crosby assures Annabelle that she is now also like a canary surrounded by cats, and she is framed through the back of a dining chair whose bars resemble those of a particularly secure cage. When Aunt Susan learn she that the entire estate has gone to Annabelle, her mental state is externalised by distorting her image, and when Cyrus’s portrait falls from the wall, there is a brief shot of the family from the painting’s viewpoint, subtly suggesting the presence of Cyrus’s ghost.

A top-flight cast is peppered with particular delights. Creighton Hale makes for an engagingly atypical hero as Paul, decked out in Harold Lloyd glasses and reacting with surprise or terror to just about everything, at least until his desire to protect Annabelle awakens his inner bravery. I adored Martha Mattox as unwaveringly stern Mammy Pleasant, something gliding along as if riding on a skateboard like the vampire in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, and at one point sidling up to Crosby in a way that is simultaneously sinister, accusatory, and uproariously funny. Forrest Stanley as Charlie really shines in a scene I can’t discuss without delivering a spoiler for newcomers, and I really liked Gertrude Astor as Cicely, who despite seemingly rather fancying Paul, has to watch while he all but ignores her in his pursuit of Annabelle, who although easily likeable is nowhere near as much fun. Most outrageous of all is Lucien Littlefield, who as Dr. Ira Lazar, the psychiatrist assigned to assess Annabelle’s sanity, is clearly modelled on Werner Krauss in Robert Wiene’s expressionist flag-waver, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and who frankly seems way madder than Annabelle could ever become.

As someone coming to this first film adaptation of The Cat and the Canary with a very personal love for the 1939 remake, I secretly expected it to play as an engaging silent prototype on which the later film was able to build. Far from it. Much (though not all) of what made the remake so creepy was lifted unmolested from Leni’s original, and even some of the key comic moments in the later film are pulled off with similar aplomb here. It’s hard to underestimate just how much the casting of Bob Hope and Paulette Godard and the quips of Walter de Leon and Lynn Starling’s screenplay bring to the 1939 movie, but artistically, the sheer inventiveness of the filmmaking here has the remake beat. It’s also every bit as entertaining as its beloved successor, a delightful comedy-horror romp that has just about everything you could want from such a work – despite being a silent film, it even has its share of amusing, albeit intertitle-based verbal gags. It also set the template for a subgenre that it effectively gave birth to, and as such proved as influential a work as any of the sound era Universal horrors that were soon to follow, and which the success of this film effectively paved the way for.

The result of a 4K restoration from the original negatives supplied by the Museum of Modern (MoMA), the 1080p presentation of the film on Eureka’s Blu-ray, framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, is every bit as glorious as was claimed by the press release for this disc. Yes, there are still plenty of traces of damage and wear throughout, but it’s so low-key here that it will largely go unnoticed, and given that this film is almost a century old, the work done to restore it to this quality is downright heroic. The original tinting has been faithfully reproduced, with night exteriors having a steely blue wash and the interiors given a warm golden hue, and while this does inevitable impact the contrast range – there are no pure whites or blacks as a result – the resulting image is still vibrant and detailed, and those small traces of wear aside, is free of damage. Given the film’s age, I couldn’t have hoped for better.

The accompanying score is by Robert Israel, and was compiled, synchronised and edited by Gillian B. Anderson, and based on music cue sheets compiled and issued for the original 1927 release. Presented here as a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, it’s a rich, tonally lively and crystal clear track that complements the film and feels period-appropriate – how I wish all silent films could be released on Blu-ray with a score drawn from the one that accompanied it on its original release. Occasional sound effects have also been added such as hands knocking on doors, which apparently is also consistent with how the film would have played in its day. Bravo all round.

Being a silent film with on-screen intertitles, there are no subtitle options.

Commentary by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman

When it comes to Eureka Blu-ray releases of horror titles, we horror fans always hope for a commentary by one of the label’s two favourite horror specialist duos, but here we’re really spoilt with separate commentaries by both of them. The first features novelist and critic Kim Newman and writer and editor Stephen Jones, who engage in a typically lively and information-packed conversation about a film they describe a hugely entertaining work that stands up incredibly well, despite being only a few years shy of being a century old. They discuss the cast, the characters, John Willard’s original stage play and his novelisation of the film (this was new to me), Paul Leni’s creative direction, this film’s influence on later works, the risqué aspect of the scene where Paul is hiding under the Aunt Susan’s bed, and a good deal more. Jones expresses enthusiasm for the idea of Kenneth Branagh directing an all-star modern remake, and they praise the music score, the creative use of depth-of-field, and the framing and character blocking. They also question why one character would go to the trouble of making up their hand for a specific scene, a query that I believe I have a logical explanation for. As this would count as a spoiler for newcomers to the story, I’ll stick it in a small font as a footnote at the bottom of the page for later reading.**

Commentary by Kevin Lyons & Jonathan Rigby

Every bit as welcome as the Jones and Newman commentary is this second one featuring the regular pairing of English Gothic author Jonathan Rigby and Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Films and Television website editor Kevin Lyons. While there is some inevitable minor crossover with the above, for the most part this compliments it handsomely, with more detailed information on the actors, director Paul Leni, screenwriters Robert F. Hill and Alfred A. Cohn, and cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton, plus quotes from reviews of both the play and the film, and even from a column by a young Ed Sullivan paying tribute to actor Creighton Hale. They praise the economy of the dialogue, the comedy of the bedroom scene, the opening prototype Universal globe and end-of-film cast listing, and a late film portrayal of madness that I can’t be specific about without delivering yet another spoiler. There’s plenty more, all of it entertaining.

Mysteries Mean Dark Corners (29:02)

A new video essay by David Cairns and Fiona Watson that explores the history of what they describe as the Spooky House Melodrama film, from its earliest incarnations right up to the 1979 remake of The Cat and the Canary. Appropriately, the film here gets specific attention, with the inventive opening scene nicely deconstructed, and there is some detailed information on the production and on Leni himself. Filmmaker quotes are read out by actors pretending to be them (complete with added crackle for a couple of the Leni ones), and in a moment that genuinely made me laugh out loud, Watson describes Creighton Hale’s portrayal of Paul Jones as someone who “looks like a digestive biscuit that’s had all the chocolate licked off it.” I almost hate to take the edge off such a brilliant observation by pointing out, in the manner of Bernard Woolley from Yes, Minister, that digestive biscuits do not have chocolate on them, only chocolate digestives do. I’m sure that’s what Watson meant.

Pamela Hutchinson Interview (13:04)

Writer and film critic Pamela Hutchinson cheerfully enthuses about a film she describes as “a complete and utter hoot” and “the funniest and creepiest version of this story.” She takes detailed look at the career of director Paul Leni, selects many of the actors for individual praise, salutes the work of art director Charles D. Hall, and comments on the film’s mix of Hollywood style and slapstick with European artistic sensibilities.

Phuong Le Interview(9:11)

Film critic Phuong Le also briefly covers the early career of Paul Leni, but her primary focus is The Cat and the Canary, its lighting, its set design, its style, and its atmosphere. She highlights the screwball comedy elements of the bedroom scene, how the animated intertitles become part of the scenery and plot, and notes the film’s cinematic fracturing of bodies and focus on hands, something also discussed by Jonathan Rigby and Kevin Lyons in their commentary.

There are two newly recorded extracts from John Willard’s original play, both directed by David Cairns and presented as audio performances and illustrated by scene-appropriate stills from the film, whose graphical style is also nicely aped by the credits here. The first, A Very Eccentric Man (3:11) covers the reading of Cyrus West’s will, and usefully elaborates on why the potential beneficiaries had to wait twenty years to hear who inherits his fortune. The second, Yeah a Cat (2:15), covers the scene in which Hendricks enters the house to warn that a dangerous man has escaped from the local psychiatric hospital. Not quite sure why this scene was picked, and I have to confess that I prefer how it’s performed in the film adaptation(s).

The final on-disc special feature is titled Lucky Strike (0:55), and consists of a newspaper ad in which director Paul Leni extols the positive virtues of Lucky Strike cigarettes. The graphical elements of the ad are animated to sequentially appear as an actor reads Leni’s words in an appropriately heavy German accent.

Booklet

The booklet here consists primarily of three excellent essays, the first of which is a perceptive examination of The Cat and the Canary by film writer Imogen Sara Smith, one that highlights the influence of German Expressionism on Leni’s direction. This is followed by an even more in-depth look at the film, its influence, and its place in the Spooky House subgenre by film scholar, writer and research Craig Ian Mann, and a third, equally fascinating piece – brilliantly titled Un Chat Andalou – by film critic and historian Richard Combs. These three essays really complement each other, and provide a comprehensive and thoughtful examination of the film, its production, and its many qualities, and together make for a rewarding and enjoyable read. Credits for the film and viewing notes have also been included, and the booklet is attractively illustrated with production and promotional imagery.

A lively and hugely entertaining horror comedy that is lifted to a higher level by director Paul Leni’s wonderfully creatively expressionistic direction. The gorgeous restoration is handsomely showcased on Eureka’s Masters of Cinema Blu-ray and supported by a strong collection of special features. Pleasingly for this fan, the film takes nothing away from Elliot Nugent’s equally delightful 1939 remake, and since both are available on Eureka Blu-ray, it’s now possible own and appreciate them equally at optimum quality. Get your hands on both and enjoy a great double-bill of delicious spooky fun. Highly recommended.

Spoiler warning – see the film first before reading what follows.

** What seems to confuse Newman and Jones is why the villain would go to the trouble of making up his hand to look monstrous when he grabs hold of lawyer Crosby and pulls him into a hidden passage in the library. They ultimately conclude it’s because he was mad, but I’d suggest there is a more logical explanation. When the villain opens the secret passage to grab Crosby, the only part of him that emerges from the darkness of the passage is that made-up hand. As he is otherwise in hiding, he would be unable to see that Laura has her back to Crosby, and could not be sure that she would not turn around before Crosby could be pulled into the hidden passageway. Similarly, when he reaches through the panel in the headboard of Annabelle’s bed to steal the necklace from her neck while she is sleeping, there was always a strong possibility that she would wake and see what he was doing. The monstrously made-up hand was thus likely for her benefit, to scare her silly and ensure that even if she did see Crosby yanked into the passageway or the attempt to steal the necklace, her claim to the others that she the deeds were committed by some sort of monster would sound like the wild ramblings of a mad woman. This would make it more likely that she would be judged insane and thus be ineligible for West’s fortune, which of course would work in the villain’s favour. Hope this helps.

|