"Art is not somewhere else; it is in life, and absolutely continuous with it." |

Ray Carney |

"To the real poet the front of the Bank of England may be as excellent a site for the

appearance of poetry as the depths of the sea . . . 'Coincidences' have the infinite

freedom of appearing anywhere, anytime, to anyone . . . probably least to petty

seekers after mystery and poetry on deserted sea-shores and in misty junk-shops." |

Humphrey Jennings |

In his 1954 Sight & Sound article, Only Connect, Lindsay Anderson famously wrote: "It might reasonably be contended that Humphrey Jennings is the only real poet the British Cinema has yet produced." Anderson's bold claim, repeated with increasing frequency of late, derives special authority from his own singular position as the missing link connecting British filmmaking and British film criticism. That Anderson made that characteristically combative comment at the expense of Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger and Carol Reed merely increased its polemical force; that he made it, too, at the expense of John Grierson, Paul Rotha, Harry Watt and Basil Wright, emphasises the stylistic distance between Jennings, the Cavalier, and his Puritan colleagues within the British documentary movement of the '30s. It is ironic that although John Grierson described documentary as "the creative treatment of actuality" and Paul Rotha, his great rival, called it "the dramatisation of fact," it was in the work of Humphrey Jennings that those phrases came to life. Jennings rarely saw eye-to-eye with those founding fathers of documentary film culture. Lindsay Anderson reminds us, elsewhere, of John Grierson's insistence that the documentary movement began "not so much in affection for film per se as in affection for national education." Anderson adds, "In other words, Grierson was suggesting that the group was inspired, not by the fiction and the romance of the movies, but by the romance of social advance, community and the technological society." Jennings shared his documentary colleagues' sense of social purpose but, as he fell in love with cinema and developed his craft in the '30s, drawing on his passion for painting and poetry to develop the lyrical voice that would move audiences to tears in the war years, his distinctive collagist style increasingly diverged from theirs.

Critic Geoffrey Nowell-Smith has rightly argued that Jennings' work, like that of his mentor and producer at the GPO Film Unit Alberto Cavalcanti, sits more comfortably within the tradition of European avant-garde and modernist experiment than that of the British documentary movement. Filmmakers as diverse as Karel Riesz and Martin Scorsese have noted that his work prefigured Italian neo-realism, particularly in his use of non-professional actors and his deployment of dramatic re-enactment. Meanwhile, online, Tomas Leach has even gone so far as to make a daring, and not completely outlandish connection between "Jennings the propaganda master" and the Third Cinema movement. Jennings' unique, comparatively flamboyant approach to documentary was certainly at odds with the more pragmatic approach of those he referred to, sardonically, as 'Grierson's boys'. Nevertheless he had no shortage of admirers, even among those of his peers who accused him, with some justification, of aestheticism.

Basil Wright, considered Jennings "a genius," while Ian 'Dal' Dalrymple, producer of many of his early GPO films, felt he "had the artist's gift for . . . the angle juste." The poet Kathleen Raine, his contemporary at Cambridge (from which he graduated with a Starred First in English), called him "one of the most remarkable imaginative intelligences of his generation." Jennings made an equally lasting impression on successive generations of British filmmakers. The Free Cinema and New Wave directors of the late '50s and early '60s acknowledged their debt to him; so, too, did the Wednesday Play/Play for Today directors of the '60s and '70s. His influence not only ran like a thread through what John Hill called the "unbroken tradition of British Realism" – influencing the likes of Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, it also permeated the work of latter-day poets of British Cinema such as Terence Davies, Derek Jarman and Patrick Keiller.

Widespread recognition has, unfortunately, lagged behind that afforded Jennings by his contemporaries and a steady stream of filmmakers subsequently. Fortunately, that has begun to change within the past decade. The broadcast of Kevin MacDougal's BBC documentary Humphrey Jennings: The Man Who Listened to Britain (2001) alerted many to Jennings' work for the first time. More recently, three important books on Jennings – Kevin Jackson's excellent authorised biography Humphrey Jennings (2004), Keith Beattie's perceptive study Humphrey Jennings (2010), and Philip C. Logan's definitive survey Humphrey Jennings and the British Documentary Film: A Re-assessment – have helped deepen understanding of Jennings' work and spread awareness of his cultural importance (and that despite Beattie's book being priced at £50 and Logan's at £70!). Logan's declared objective in re-assessing Jennings' work was "to rescue Jennings' reputation from the condition he referred to as the 'sleep of selectivity'; in other words the failure of the imagination to make connections," – connections, that is, between his interlinked work as observer of working class life, painter, poet, surrealist and documentary filmmaker. Now, over half a century after Jennings' untimely death in 1950, the British Film Institute's welcome, if belated release of The Complete Humphrey Jennings arrives to cement his standing among the greats of world cinema, and to help us appreciate his work in all its variety and complexity.

There are dangers lurking here: monumental reputations are often set in stone at the expense of vivacious critical engagement, and particularly brilliant films by sanctified directors are often singled out to the detriment of their wider work. We might call this process "Citizen Kane syndrome." In Anderson's case, the reputation was built around If.... (1968); in Jennings' case the film is Fires Were Started (1943). Where Jennings is concerned, matters are further complicated by the difficulty of separating his reputation from its fixed base in Britain's "finest hour" and assessing his role in the creation of national myth. Many of his more interesting achievements remain in the shadows due to the dazzling brilliance of his wartime films London Can Take It (1940) – two versions of which are included in this volume, Words for Battle (1941), Listen to Britain (1942), Fires Were Started (1943), and Diary for Timothy (1945).

The 15 films in this initial volume offer us an opportunity to track Jennings' steady development, from his first awkward efforts through to the accomplished finesse of his early wartime films. Those familiar with Jennings' work will have felt a quickening of the pulse when they learned of the BFI's plans to gather all his films together in one extraordinary three-volume, dual-format collection. Others, less familiar with his work, may be disappointed by what they find in Volume One: The First Days; for, while it contains much magnificent material, it also includes films of such startling mediocrity that they would surely have remained in the archive vaults were Jennings' name not attached to them. The films here are all fascinating in their own right, though, even the worst of them, as markers in Jennings' development, but also as important social documents.

As Cervantes said, "There is no book so bad that there is not some good in it." That dictum has equal application to films, so I shall treat all those assembled in this volume on their own merits. It is impossible to understand Jennings without considering notions of national identity and representations of war, the politics of documentary and class politics, but I shall keep my powder dry for the impatiently awaited second and third volumes in the collection, due out next year. I will restrict myself here to précis of certain important ideas contained in the work of Jackson, Beattie and Logan, and offer a few thoughts on baffling imperfections within Jennings' wonderful work.

A gifted art critic, set designer, painter, photographer and poet, Jennings joined John Grierson's team at the GPO in 1934, as a raw recruit, without either experience or any great love of film. He entered film partly motivated by the need for money after the birth of his first daughter and arrived at the GPO hot foot from Paris after an unsuccessful attempt to establish himself as a painter. Jennings learned his filmmaking craft on the job; creating his own rules, learning from his own mistakes, inventing and experimenting as he found his métier and mastered his medium. As his films became progressively more polished throughout the '30's, his style was increasingly informed by his politics and his passion for painting and poetry. By the time the war arrived Jennings was ready to meet his destiny: to create films that spoke of and to a people at its most embattled and best, films that showed the nation to itself while, to some degree, shaping the nation's sense of itself.

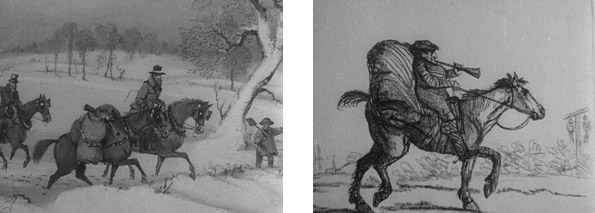

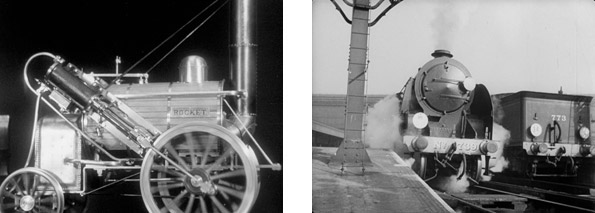

Jennings' lack of formal training is all too evident in his rough-edged early work. The first three films in this volume were all made in 1934, the year John Grierson and Stephen Tallents founded the GPO Film Unit, the phoenix that arose from the ashes of the Empire Marketing Board. Post Haste, Locomotives and The Story of the Wheel (1935) are rudimentary, unimpressive educational films made by the GPO for screening in schools. Basic though they are, these films do educate. Do you know how the wheel was invented? Or that trains began in mines? Or how the Post Office grew? They fulfil their pedagogical purpose admirably, despite, or, bearing in mind their intended audience, because of their primitive appearance. There is also more to them stylistically than initially meets the eye. Even in the first of these films, Post Haste, a history of the Post Office and the Royal Mail, there are signs of invention. As a Postal service courier trumpets the arrival of a great filmmaking talent, the camera pans across visual materials gleaned from the British Museum and the Postal Museum, to the accompaniment of a serviceable commentary. As Katy McGahan says in her liner notes on the film, the use of two-dimensional materials in documentary, something we now take for granted, was innovative for its day. Post Haste may seem slight and simple by contemporary standards but it was among the first films to use still images this way. The use of film for educational purposes was equally groundbreaking.

As The Story of the Wheel opens, we are informed that: "Many of the beautiful pictures, models and dioramas used in this film can be seen in the British Museum, the London Museum and the Science Museum." Some of the models used in this film and Locomotives strike contemporary eyes as comically basic and will raise a smile. They may also take those of a certain age back to children's TV programme such as Blue Peter ("Here's one I made earlier"), Camberwick Green, Trumpton, or, more pertinently, to Postman Pat and his black and white cat. It would be easy to scoff, but Jennings did what he could with his sponsors' briefs, with the raw material at his disposal and his own technical limitations.

In looking at the films in Jennings' learning period, it is important to bear in mind that the GPO Film Unit worked collaboratively; sharing resources, discussing ongoing projects and trading ideas. We have to look hard, therefore, to see Jennings' hand at work. His insatiable curiosity is apparent even here though, most obviously in the marked references to trains that occur in Post Haste and Locomotives, and the brief appearances of them in The Story of the Wheel and Penny Journey (1938). Jennings' also reflected on trains in his prose poem The Iron Horse (1938), a work that formed the basis for his literary magnum opus Pandæmonium: The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers. Published by Picador in 1985, in an edition edited by Jennings' daughter, Mary-Lou Jennings, and his friend, Charles Madge, Pandæmonium is a sweeping meditation on industrialisation. It is similar in form to Walter Benjamin's The Arcades Project, and just as Benjamin's masterpiece was an unfinished lifetime's project, so, too, was Pandæmonium for Jennings.

The Industrial Revolution, the benefits and negative consequences of technological innovation, and the advent of the railways were themes that fascinated Jennings, themes that fortuitously squared with the GPO's desire to promote the increased speed with which post was being delivered. Jennings was a modernist in a country that largely rejected Modernism and the train was a symbol of modernity and industrialisation for him, as it was for much of the avant-garde in the '20s and '30s. Trains are present in many of his early films; in the three discussed above, in Farewell Topsails (1937), and in Penny Journey (1938). But Jennings was ambivalent about technology. At times he celebrates it. In The Story of the Wheel it is an unmitigated good; in Locomotives, with its fetishistic close-ups of pistons and wheels, it is the harbinger of efficiency; in Spring Offensive (1940) a belching, heaving gyro-tiller saves the day; in Speaking of America (1938) it provides new means of communication; and, in his last film, Family Portrait (1950), it is the motor of history and change. Elsewhere, Jennings strikes a Luddite note as he rues the consequences of technology. In Farewell Topsails (1937) "steam and motor craft" edge out ocean-going schooners like the Jane Banks and The Waterwitch, which lie rotting on the mudflats, "finished"; in The Farm (1938), the age of mechanisation results in "Phyllis the milkmaid" being similarly rendered redundant, in this case by an automatic metal milking device; and in Diary of Timothy (1945) technological change has damaged social and political life.

In The Birth of the Robot (1936), which the BFI has, thankfully, included in the extras to this release, technology is again a positive force – as well it might be, for the film was sponsored by the oil company Shell-Mex. The piper calls the tune. Made in collaboration with his friend Len Lye, this animated film was also made to promote Gasparcolor, for whom Jennings worked in the year of the film's production. A smiling motorist and his grinning car cruise the Egyptian pyramids before, inexplicably, heading off into the dessert. After they are, unsurprisingly, caught in a sandstorm, the driver dies and rots away to his bare bones. Venus sprinkles a few drops of Shell-Mex oil from the heavens and the skeleton is revitalised, as a Shell-Mex robot. This inventive, lively film offers early proof of Jennings' willingness to experiment and to collaborate with others.

That slightly surreal oddity within Jennings' oeuvre was the first in a series of films that he made to promote newly developed three-colour film processes. Four followed in the period during which Jennings worked as freelance film director: Farewell Topsails, Design for Spring (1938), and two versions of the same film – The Farm (1938) and English Harvest (1939). These films were made using, not Gasparcolor, but Dufaycolor (the colour process of a rival company, Dufay-Chromex), which had first been road-tested in 1931. Earlier three-colour reproduction processes, such as those pioneered by Gaumont, had relied on triple-lens cameras – which filmed through red, green and blue filters – combined with three lens projectors. No matter how skilled the projectionist responsible for setting the coloured lenses, this process always resulted in a blurring of colours, known as 'colour fringing'. The British Gasparcolor and Dufaycolor 'additive' processes sought to rectify this problem by adding coloured filters to the film base itself, which were then coated in emulsion and exposed within the camera. Although these colour filters blocked most of the light from the projector, darkening the projected image, the colour reproduction quality was pretty decent, even when viewed through spoilt contemporary eyes.

Given that Jennings made Farewell Topsails, The Farm and English Harvest as a freelance director, it seems safe to assume that he had more freedom to decide upon his subject matter than he did either while working with Len Lye, on the Shell-Mex film, or for Grierson and Cavalcanti on GPO films. These later films, like Jennings first three films, reflect his ongoing interest in the effects of industrialisation and his ambiguous feelings about technology. They contrast the peace of rural England with the noise of machinery, the ancient with the modern. They are neatly composed and possess a lyrical lilt that hints at what is to come from Jennings. The mournful, melancholic respect for the past that underpins these records of the passing of tall ships and country ways tugs at the heart strings. Here are sure signs of Jennings' capacity to connect with and move an audience. These are lovely, fascinating and well-crafted films. Each records a way of life that has since vanished so they also stand as vital social documents. Watching these films, knowing as we do that the war is just around the corner, and that Fires Were Started was just 10 years down the line, one is struck both by their delightful innocence and by how far and how fast Jennings came. It is noticeable that in these films Jennings now shows himself to be far more interested in people than things. He displays an empathy for his human subjects absent from his first films. It is as if Jennings' humanity and his politics were improving in parallel with his filmmaking skills, or so it would seem if it were not for the last in this group of Dufaycolor films, Design for Spring, aka Making Fashion.

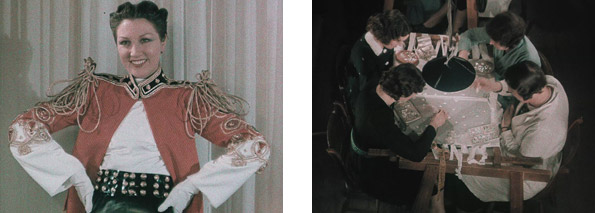

Design for Spring will be the film of the collection for those interested in fashion and frocks, as it is essentially an ad for Noman Hartnell – the doyen of haute couture, designer of dresses for duchesses, dowagers and royals. Those less interested in dresses, perhaps especially those made of monkey fur or encrusted in pearls and diamonds, might find the film dull. It shows nothing much beyond dresses, emaciated mannequins and conspicuous consumption. The pin-ups of the day – Bing Crosby, Robert Taylor, Spencer Tracey – look on as the seamstresses toil in their workroom to create the outrageously expensive garments others will wear. Dorothy Parker famously said that the only 'ism that Hollywood truly believed in was plagiarism; Design for Spring raises questions about the depth of Jennings' professed commitment to socialism and the New Jerusalem. At the very least, Jennings showed a lack of restraint and empathy when he chose to make this film, with mass unemployment and the Means Test still destroying people's peace of mind and fascism on the march across Europe. Worse things happen at sea than insensitivity of course and we are in no position to judge Jennings from any kind of moral high ground. Ours is, after all, an era characterised by shabby compromise and over-consumption, millions still walk to work at dawn weighed down by worry while others sleep on soundly in feather beds, and we can all name contemporary artists who have sold themselves and their art short for financial gain. Besides, it will be argued, Jennings had a family to support and a mortgage to pay, just as many of those unemployed in his day did. An argument countered in Jason Reltman's satire Thank You for Smoking (2006) when spivvy Nick Taylor says: "Everyone has a mortgage to the pay," while thinking, "The Yuppie Nuremberg Defence." The past informs the present, so we do judge our forebears, according to our politics, while bearing in mind human imperfection. The point here, though, is not the act but its implications.

Jennings' injudicious decision to make this film may betoken a lack of sensitivity and political sincerity, but it also highlights the distance between him and his subjects, and throws interesting light on his work. This business of Design for Spring is all the more baffling and disappointing because awareness of inequality was brought into sharp focus for Jennings himself during his stay, in 1937, in the home of an unemployed spinner in Bolton. It was a visit that changed Jennings' life, political perspective and filmmaking practise for good. I mention Design for Spring, an isolated episode in Jennings' career, not just because it ruffles my feathers but also because Jennings' recognition of the contradictions inherent in his class position, and those within his own personality, produced a significant improvement in his work. Jennings was a mass of observable contradictions: he was a highbrow intellectual who respected popular culture, a socialist with a stake in the status quo, a modernist with a strong sense of his country's past, and a republican who felt the monarchy bound the nation. Those contradictions are part of the reason why Jennings so enthusiastically embraced radical ambiguity, a choice that took him far further than awareness of the ambiguities inherent in technological progress noted above.

At Cambridge he produced the journal Experiment with William Epsom, author of Seven Types of Ambiguity – a landmark work of critical theory that foregrounds complexity and coincidence. Jennings' heightened sense of ambiguity informed, and was shaped by his attraction to Surrealism. He helped establish the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936 – with the Anarchist Herbert Reed, the Pacifist Roland Penrose and the Communist Louis Aragon. Jennings' own Surrealist paintings were shown there beside work by Salvidor Dalí and Max Ernst. The influence of Surrealism is apparent in his willingness to experiment and in the technique of collage and juxtaposition, which increasingly defined his work. As Keith Beattie says: "Ambiguity . . . is the most cogent definition of the 'poetry' in his documentaries. Ambiguity is a structural principle within Jennings' films and is central to the forms through which Jennings represented content . . . (reflecting) the complexities inherent in everyday experience, what the theorist of film realism, André Bazin, was to refer to as the 'imminent ambiguity of reality'."

Jennings' predilection for collage first announces itself in Spare Time (1939), a magnificent film marked by his involvement with the Mass Observation movement. Founded by Jennings, Tom Harrisson and Charles Madge in 1936 with the declared intention to create "an anthropology of ourselves," Mass Observation implicitly attempted to understand and record the experience of the working classes, 'themselves'. In order to make Mass Observation a reality, Jennings secured the support of many of his muckers from Cambridge, including Charles Madge, William Epsom, and Kathleen Raine. The project was initiated at a time when metropolitan intellectuals were "going native" and venturing into the Industrial North Country, a foreign land to them, to witness at first hand social conditions of which they had little direct experience. The best known such sortie resulted in George's Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). In his forward to the Left Book Club edition of that book, publisher Victor Gollancz described its aim as to being to record working class life in Wigan and reveal a "terrible record of evil conditions, foul housing, wretched pay, hopeless unemployment and the villainies of the Means Test." Jennings, incidentally, admired, and was hugely influenced by Orwell. It is remarkable that two of the great figures of British culture of the 30s and 40s grew up a short walk away from one another on the Suffolk coast, in Walberswick and Southwold respectively. Mary-Lou Jennings has even unearthed a 1919 photograph that shows the two together as boys. They can be productively compared and I will return to Orwell below, and to his 1941 essay The Lion and the Unicorn when I review volumes two and three.

There are obvious similarities of purpose behind Mass Observation, Orwell's book, and the Left Book Club, which was also founded in 1936, to make books of political importance available cheaply "so that the people might know and no longer be deceived." Their approaches, though, were very different: while Orwell relied on facts, and the same acute observation and scalpel-sharp descriptive prose he had deployed in Down and Out in Paris and London, Mass Observation eschewed straight reportage and the accumulation of statistics in favour of an impressionistic approach, one that build up a picture of working life through the coincidences and granular detail of everyday life – happenings, hobbies and habits, but also "beards, armpits, eyebrows." From its inception there were differences of opinion in how Mass Observation should operate, and Jennings became increasingly impatient with his associates, as they opted to replicate the methodologies of conventional anthropology and sociology. But although he had all but withdrawn from the project before he made Spare Time, the lessons he learned through his involvement had a powerful influence on his work. Surrealism shaped his approach to the Mass Observation project, which in turn opened his eyes to the possibilities of a collagist approach to documentary.

Spare Time, made as part of the British contribution to the New York World Fair, marked a radical and influential departure from the more nuts-and-bolts, matter-of-fact style of the British documentary movement as a whole. The Free Cinema filmmakers regarded the film as an exemplary model of documentary cinema, and favoured Jennings over Grierson. The film builds on Jennings' experience with the Mass Observation project, "Worktown," which considered aspects of life in Bolton, and is shaped by his politicising stay there. Jennings' film ventured where few British films had done before, and where he himself had only recently gone, into working class communities. Spare Time considers the leisure time of those employed in three industries: Coal (Pontypridd), Cotton (Bolton and Manchester) and Steel (Sheffield). The film's ebullient atmosphere reflects the excitement Jennings felt upon encountering the vivacity and variety of working class culture for the first time. His wartime films are stamped with the respect he immediately came to feel for the ordinary citizen. It is stamped too with respect for that self-generating culture of self-improvement, mutual aid and resistance described by Jonathan Rose in The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, and, later, in its dying moments, by Richard Hoggart in The Uses of Literacy. After the Dufaycolor commissions and the aberration of Design for Spring, perhaps as a result of it, Jennings returned to the GPO in 1938, with a heightened sense of social purpose. As Philip C. Logan notes: "His personal and artistic concerns about the relationship between poetry and life had now been overlain and informed by a sharper social and political awareness. It was an awareness matched by a continued search for appropriate techniques of communication, by which the general public . . . could find relevance in the messages coming from the artist-poet to their everyday lives."

Jennings' subject matter and radical use of collage in Spare Time makes it the founding film of Poetic Realism. It is also one of the most important films produced by the British documentary movement. Good ideas spread like wildfire and many of those developed by Jennings were subsequently taken on board by filmmakers working for the organisations that superseded the GPO Film Unit: the Crown Film Unit (1940-52), the Ministry of Information (1940-45), and the Central Office of Information (1946- 2012)* As I noted in my recent review of the BFI's fifth collection of COI films, Portrait of a People, the 1949 COI film Come Saturday was clearly modelled on Spare Time. Like Jennings' film it presents images of the English at play and mythologizes rural England. It also reflects Jennings' suspicion of heavy-handed "voice of God" narration. Ralph Richardson introduces the film and winds it down, but, otherwise, there is no commentary.

Jennings' attitude towards commentary was complex, and it sometimes feels as if there is a tug of war taking place between his painterly sense of the visual and his poet's love of language. Jennings generally struck a perfect balance between images and words but, occasionally, words threaten to overwhelm the images, as they do in his later film Words for Battle (1941). As its title suggests, this film deployed a chorus of poetic echoes from the English past in order to rally the nation; words from Blake, Browning, Churchill, Milton and Kipling. Once again, Jennings' innovations were later adapted at the COI. In the title film of the above-mentioned COI collection, Anthony Pelissier's Portrait of a People (1970), words, including Churchill's again, are used in identical fashion, to rouse and bind the nation. As Keith Beattie points out, Words for Battle was the first wartime film to press the past into service as means of promoting national unity. This ideological use of the past later became central to representations of national identity, and is now locked into place, in bastardised form, in Heritage cinema. That is an argument to which I will return when I consider Jennings later wartime films, those contained in volumes two and three of the collection.

In a Time and Tide film review of 1941, Orwell complained about the commentaries in documentaries. Attacking the MOI's Unholy War (1941) and Jennings' Crown Film Unit film The Heart of Britain (1941), he said: "Since films of this kind need a spoken commentary, why cannot the MOI choose someone who speaks the English language as it is spoken in the street? Some day perhaps it will be realized that that dreadful BBC voice, with its blurred vowels, antagonizes the whole English-speaking world except for a small area in southern England, and is more valuable to Hitler than a dozen new submarines." Orwell, whose nasal Old Etonian accent we will never hear, was right to complain but unfair on Jennings. It is clear that Jennings was aware of the problems presented by commentary. The grating cut-glass accents of Jennings early films gradually made way, as war approached, for gentler, more democratic voices, and he increasingly cut back commentary, to allow the images to breath. English Harvest (1939), an alternative version of The Farm (1938), is instructive in this respect. As Michael Brooke comments in his liner notes, these are two very different films and, in editing the later film, Jennings reduced the word count from several hundred to a couple of hundred. He also replaced the chummy, jolly-hockey-sticks commentator of the earlier film with popular writer and broadcaster A G Street, whose rural burr is much easier on the ear. Street also provided the commentary for Jennings' Spring Offensive (1940). In Spare Time the commentary is provided by International Brigade volunteer Laurie Lee; for Welfare of the Workers (1940) Jennings called upon Scottish socialist, sociologist and popular science writer Ritchie Calder; and in London Can Take It! he uses the wonderfully warm, fireside-chat tones of American journalist Quentin Reynolds.

When he wrote Only Connect, Lindsay Anderson was as unfamiliar with Jennings' early work as most of us will have been before this essential BFI release. He suggests that Jennings began directing films in 1939, with Spare Time. Dismissing The Birth of the Robot as "an insignificant experiment," and Speaking from American as impersonal, Anderson says: "The date is significant, for it was the war that fertilised his talent and created the conditions in which his best work was produced." It is hard to disagree. Jennings' work becomes ever more moving and urgent as war approaches. Watching the films in this collection chronologically is to experience a growing sense of tension at the darkness slowly engulfing Europe as the lights went out all over, all over again. The BFI's inclusion among the extras of Cargoes (1940), a later, alternative version of SS Ionian (1939), is, again, instructive. In its first incarnation the film is a fascinating, if anodyne account of the voyage of a merchant vessel; in its second version we hear the ominous, unmistakable sound of war drums. We are now told that the merchant marine is supplying the Navy with men as well as the nation with food, while the Navy protects the merchant fleet against enemy attack.

The loud, clear message is repeated from here on: "OK, it's here folks, we're all in this together, keep your chins up, we'll win smiling." That same message is there in The First Days (1939), an impressionistic poetic report upon the "Phoney War" period of patient preparation for an invasion that didn't immediately materialise; in Spring Offensive, which reflects upon the battle to increase food production and reclaim derelict rural land; and in Welfare of the Workers, a story of sacrifice, in which organised labour voluntarily relinquishes hard-won workplace rights after being asked "to give up by choice what Hitler takes by force." Finally, as the collection ends and the bombing begins, we are treated to the best film in this volume, a masterpiece of moving public poetry and effective propaganda, London Can Take It!

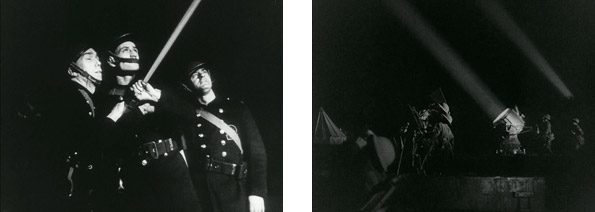

Made on the hoof by Jennings, Pat Jackson and Harry Watt, London Can Take It! tells the story of a day in London's life during the Blitz. It is propaganda certainly, but propaganda raised to the level of high art and it is, most definitely, poetry of the highest order. Not for nothing has Kevin Jackson referred to Jennings as our "Whitman of the Blitz." London Can Take It! moves us just as deeply as it did those who first watched it in the factories and barracks of embattled Britain and rose as one to cheer it. Perhaps we feel the film's force with particular intensity today, because its images pulse with the power of defining national myth, because we feel a surge of pride in ourselves as a people by identifying with ourselves as that people. Made in a fortnight, in the aftermath of the Battle of Britain, the film opens with an iconic image of St Paul's cathedral before showing people, "part of the greatest civilian army the world has ever seen," walking home from work to face another night of aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe. Big Ben strikes. The air raid sirens scream. The House of Commons and anti-aircraft batteries are silhouetted against the deepening dusk. London waits. "Here they come." The distant drone grows louder as the Nazis draws closer. "The searchlight points long, white inquisitive fingers into the dark night." The city is pounded but defiantly rises again to fight another day. The compositional beauty of the black and white images is matched by that of the language used, but they are as nothing to the beauty of the human courage described.

For one last time in this volume the BFI do us the great service of offering clues as to how the film works its magic, in the form of two versions of the 'same' film. The shorter version presented to the Home Front public, and to us among the extras, was titled Britain Can Take It! out of respect for those undergoing blitzes in Belfast, Bristol, Coventry, Hull, Glasgow, Liverpool and elsewhere. It is a powerful film, but London Can Take It!, the version destined for the USA and watched appreciatively by Roosevelt in the White House, is yet more so. The nation's cry for help is more measured, as is Quentin Reynolds' magnificently modulated delivery of a scintillating script that humanises London. One moment "she" is a woman in danger: "London raises her head, shakes the debris of the night from her hair, and takes stock of the damage done. London has been hurt in the night." Next moment, "he" is a courageous boxer: "The sign of a great fighter in the ring is, can he get up from the floor after being knocked down. London does this every night." Women and men are fighting the People's War side by side: "The People's Army of volunteers is ready. They are the ones who are really fighting this war – the Firemen, the air raid wardens, the ambulance drivers."

We might raise our modern eyes to our ceilings at the occasional dollop of overblown Churchillian rhetoric, but the general air of gravity is leavened with a lightness of touch and seasoned with sardonic humour, so, as Reynolds presents his perfectly pitched plea from the war-torn heart of "the free world," we lean in to listen, mesmerised. As Lindsay Anderson suggests, Jennings was the right man in the right place in the war, at a time when "people become important" and observation of them was more readily accepted as a reasonable subject for film. Jennings had come to admire ordinary men and women and so was ready to produce his hymns to their extraordinary heroism. Anderson – no more an uncritical, flag-waving patriot than Jennings or Orwell – put it beautifully when speaking of Jennings at his wartime best: "It needed the hot blast of war to warm him to passion, to quicken his symbols to emotional as well as intellectual significance . . . His wartime films stand alone; and they are sufficient achievement. They will last because they were true to their time, and because the depth of feeing in them can never fail to communicate itself. They will speak for us to posterity, saying: 'This is what it was like. This is what we were like – the best of us'." Looking back, as we now do, from posterity, perhaps with a sense of sadness at what we've become, we can only thank Humphrey Jennings and the BFI for reminding us of that moment.

*In an act of comprehensive cultural vandalism, the Cabinet Office recently announced that the Central Office of Information is to be closed on 1 April 2012. No, this is not the prank of a mischievous office junior; unelected public servants in Whitehall have decided to end over 60 years of public information filmmaking, thus breaking the proud tradition of which Alberto Cavalcanti, John Grierson, Paul Rotha, Humphrey Jennings, Harry Watt, et al were an important part, a tradition stretching back across a century to the Ministry of Information's formation in the First World War.

Part 2: The Films and the disc >>

|