| “A truly wacked-out work of art.” |

| Critic John Beifuss on Corruption |

Sir John Rowan (Peter Cushing) appears to have it all. A brilliant and successful cosmetic surgeon who is respected by his peers, he is soon to marry Lynn Nolan (Sue Lloyd), an attractive and successful photographic model who is a good twenty years his junior and adores him. One evening, John is relaxing at home after a tiring day when Lynn phones to remind him that they’re expected at the sort of groovy late-1960s party that probably only ever existed in movies. It’s one that the polite and conservatively dressed John feels just a little out of place at, but the lively Lynn is right at home and soon dancing and posing for photographer Mike Orme (Anthony Booth), who’s probably her ex-boyfriend and one of those 60s movie snappers who calls everyone ‘baby’ and fires off his camera at anything that moves, whatever the light levels. When Lynn cheerfully responds to Mike’s encouragement to get sexy and loosen up her dress, John intervenes, and in the resulting scuffle with Mike, a scalding hot floodlight is knocked over and falls directly onto the unfortunate Lynn’s face.

Emergency treatment is administered by John’s humourless colleague, Dr. Steve Harris (Noel Trevarthen), but despite his best efforts, Lynn is left with a large and disfiguring facial burn. The news leaves Lynn distraught, something the arrival of her caring sister Val (Kate O'Mara) does little to ease. Tortured by guilt, John desperately starts searching through all manner of texts for a procedure that might help him restore his wife’s former beauty. His hard work and dedication eventually pay off when he develops a new technique that involves extracting material from a human pituitary gland, which John plans to use to manipulate Lynn’s endocrine system and promote new tissue growth. I’ll be honest, I’ve typed that up from what I heard John tell Steve, but I don’t understand it or even know if it has any basis in real-world science. But like the surgical techniques outlined in early David Cronenberg body horror movies, it sounds convincing enough so it serves its narrative purpose.

To procure a fresh pituitary gland, John visits the hospital morgue and bluffs his way into performing an autopsy on a recently deceased woman, a procedure that Dr. Steve was due to do that afternoon. When he arrives, he gets all kinds of outraged. “You’ve broken every known rule of ethics!” he barks angrily at his colleague. Really? All of them? Hardly seems likely, and since John also determined the unfortunate woman’s true cause of death, Steve should be grateful that John saved him a job. Then, using the extracted fluid and a medical laser that has Chekhov’s Gun written all over it and assisted by the untrained hands of the anxious Val, John sets to work. When Steve visits for dinner a couple of days later, he’s astonished to see that Lynn’s face has been completely restored, which effectively shuts down his previous angry babbling about ethics. The now delighted John and Lynn decide to take a cruise to unwind from the stress of it all, which gives Steve time to get friendly with Val, something the film thankfully wastes little screen time on. All seems to be going well until Steve receives a postcard from John informing him that he and Lynn are cutting their holiday short and heading back home. What could be the problem? Unsurprisingly for us horror fans, John’s miraculous regeneration process has proven to be only a temporary solution, and Lynn’s previous facial disfigurement has returned. A further operation is clearly needed, but what John needs this time is an altogether fresher pituitary gland, and there’s only one sure way to procure that…

If any of this has a familiar ring, it’s because the central conceit has been influenced, adapted, borrowed, pinched – pick your own verb – from Georges Franju’s hugely influential 1960 masterpiece, Eyes Without a Face. It certainly wasn’t the first film to drink from the Franju well, with previous takes on the story including Anton Giulio Majano’s Atom Age Vampire [Seddok, l'erede di Satana] (1960) and Jesús Franco’s The Awful Dr. Orloff [Gritos en la noche] (1962). But it’s worth remembering that Franju’s film didn’t achieve cult classic status or even attract that much positive critical reaction until its 1986 re-release, and the hostile review of Corruption by Penelope Mortimer for The Observer that is twice quoted in the special features here is grimly similar in tone to one written by Isabel Quigly for The Spectator when reviewing Eyes Without a Face. Time, it seems, did not heal the response to extreme facial wounds and their unorthodox treatment.

This take on the story’s ace-in-the-hole, as it was with so many British horror works of the period, is the casting of Peter Cushing in the role of John Rowan. Cushing may have been one of the film’s later dissenters, but he’s at his formidable best here, something often evident in the smallest of looks or changes of expression, which tell all you need to know about what John is feeling without the need for expository dialogue. A particular early highlight comes when he elects to kill a sex worker in her room – his awkwardness at being there and his tortured reluctance to commit his first murder gives way to a frenzied despair as he cuts off the poor girl’s head. It’s a tough scene to watch in either version of the scene (see below for more on this). The UK cut in particular flips the opening sequence of Peeping Tom by making the victim rather likeable and her assailant the most reluctant of murderers. I also have to give props to actor Jan Waters here, who as the unnamed sex worker puts on a posh voice for this distinguished-looking client, then switches to her regular East End accent when he fails to react, asking a mere five pounds for her services. Prices, I hear, have risen considerably since.

This focussing on the suffering of the victim continues after John and Lynn move to their idyllic seaside cottage in Seaford to get away from the city. Here, the treatment once again shows signs of reversing, so John attacks a woman on one of those compartment trains that were phased out in part because of all the attacks on women. Concerned about from the moment she lays eyes on the nervous John, the girl fights him for all she’s worth in a scene that will likely have audience loyalties in a complete turmoil. By this point, the self-centred and increasingly unstable Lynn is emerging as the film’s true monster, angrily demanding that her husband procure the glands required for treatment, orders that the blindly devoted John feels obliged to follow. Thus, when Lynn spies lone young hitchhiker Terry (Wendy Varnals) on the beach below, she is almost salivating at the prospect of getting at her pituitary gland and sends John down to invite her to the house for dinner. But all, it turns out, is not what it seems…

While Cushing’s performance is justification enough to spend time with Corruption, there are other reasons to recommend it, at least to the more adventurous and tolerant genre fan. It’s worth noting that it was made at the tail end of a decade in which art, society and politics were turned on their head by a rebellious counterculture generation for whom sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll were lifestyle watchwords. With this in mind, while watching its second half, I began to suspect that there had been a calculated decision on Indicator’s part to release this Blu-ray alongside the 1970 drama, The People Next Door. That film was about a young girl addicted to LSD, while this one plays at times like it was made by someone under the influence of the very same drug. But before I expand on this, I’ve been advised by my legal representative to warn you that there are spoilers for newcomers in the following paragraph, so I’d skip ahead one if you wat to go into the film cold.

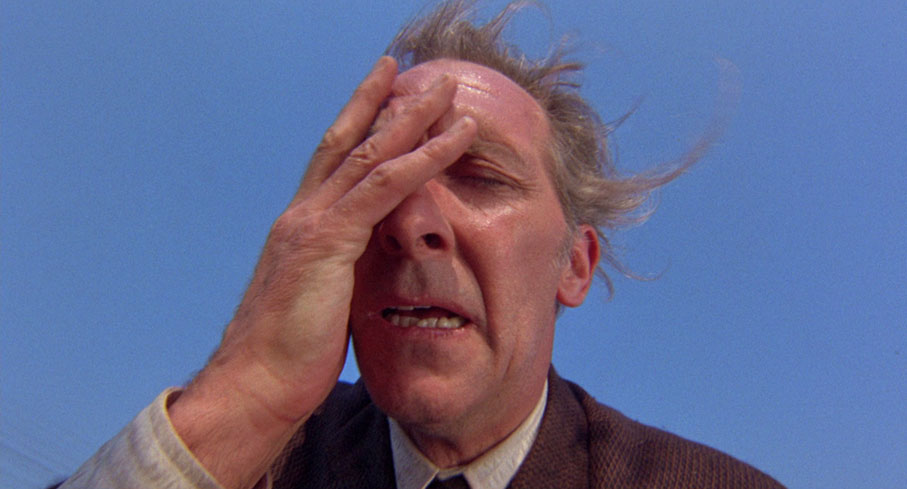

The early signs of where director Robert Hartford-Davis would be taking the film later come at the tail end of the first murder, when John is observed through a fish-eye lens from what looks like the point-of-view of the head he is removing. This distorts his face and emphasises his sweaty anxiety in what was likely intended as an expressionistic representation of his inner torment. It won’t be the last time Hartford Davis employs this technique, but he’s just getting started here. A chase across the bay below the Seaford cottage is riddled with perspective-emphasising wide-angle shots and urgent hand-held camerawork, and it’s given a slightly surrealistic feel by the decision to slightly speed up the action, a move that should provoke giggles but only seems to add to the sense of wild panic the runs through this scene. But it’s when the cottage is invaded by the gang of hoodlums that the film seems to lose any grip it had on sanity. It’s a turn of events that prompted more than one double-take on my part, coming out of nowhere and with quartet of malefactors who are neatly described by actor Billy Murray (who plays one of them, Terry’s boyfriend, Rik) in the extras as caricatures of what the filmmakers imagined gangs of the period were like. They’re led by the hip-looking, Carnaby Street-dressed Georgie (Phillip Manikum), and include in their number the aforementioned Rik, the hard-nosed Sandy (Alexandra Dane – I rather liked her) and a character you’ll have to see the film to believe. His name – I kid you not – is Groper, and he’s played by an almost unrecognisable David Lodge. Groper is a mentally challenged and constantly gurning goon who wears bottle lens glasses that distort his eyes, eats apples by crushing them with his hands and slurping the pulp through demented giggles, and follows every order dished out by Georgie with madly chuckling gusto. I’m not even going to get into his dress sense here. Groper is a cartoon in human form, but in one of the increasingly mad sequences that follow, he forces Lynn to reveal what has happened to Terry by violently jamming the rim of a brandy glass against her mouth. The very idea that this glass might shatter and slice her face to pieces had me genuinely tensed up, and given Lynn’s psychosis about facial disfigurement, it’s no wonder she blurts out what her husband is still risking bodily injury to deny. It all builds to a climax that I’ll stop short of revealing, but know that I sat watching with my eyes wide in disbelief, convinced that Hartford-Davis had by this point either taken leave of his senses or swallowed the wrong pills with his morning coffee.

So what to make of Corruption? It’s nuts, no question about it, but in what I would argue is a purposeful way. There’s just a whiff of sublimely out-of-control Ken Russell about some of the handling, from the use of distorting wide-angle lenses to a growing sense of madness that tips over into climactic hysteria to deliver as destructive a finale as you’ll find anywhere in late 60s British horror. The core story may have become a bit of a horror stalwart, but by making their murderer a reluctant pawn of his increasingly demented wife and making sure the suffering of his victims registers, Hartford-Davis and screenwriters Donald and Derek Ford give the tale a distinctive edge. For my money, you can keep Bill McGuffie’s inappropriate and distracting jazz score, and Lynn’s facial burn makeup never really convinces, but Cushing is magnificent, the supporting players are fun, the violence is still jarring, and cinematographer Peter Newbrook was clearly game to go wherever his director and production company partner was unafraid to wildly leap. Seriously, how could I dislike this film? Be warned, if you watch it while on drugs, your head might explode, though you’ll likely be brought back down to Earth by an ending that runs the risk of casting all that went before as, well… no, I think I’ll leave that one for you all to ponder on yourselves.

Included on this Blu-ray are three alternative cuts of the film. When you select Play Film from the main menu, you’re presented with four options:

- Play UK Theatrical Cut (92 mins)

- Play US Theatrical Cut (92 mins)

- Play Continental Version (91 mins)

- Play Isolated Music and Effects Track

Given my feelings about the music score, I opted to give that last one a miss, but if you like it, enjoy! Anyway, sitting below these options is a textual overview of the differences between the three versions. One bit of advice. If you’re new to the film, DON’T READ IT YET, as it contains a couple of major spoilers.

The biggest difference between the versions lies in the handling of the first murder, and we’re not just talking about the snipping of a few shots here. In the UK and USA cuts, the sex worker is played by Jan Waters, who initially greets John in a faux-friendly manner, takes a call from a friend, then approaches John dressed in a bathrobe and underwear. She offers him gentle words of encouragement, then gives him a hug. In the film’s first (though not its most extreme) hallucinatory sequence, the visibly sweating and borderline traumatised John hears the anguished screams of his wife in his head as the editing of close-ups builds effectively in pace (some really nice work by editor Don Deacon here). John then lets a hidden knife slide out of his sleeve, with which stabs the woman as she holds on to him. Deeply shocked, she slides to the floor and dies. Midway though this sequence is an intriguing close-up of the back of the woman’s neck, observed by John as he contemplates what he has to do.

The same moment from the UK/USA version (above) and the Continental version (below)

In the Continental version, the woman is played instead by Marian Collins, who greets John in a more brusquely matter-of-fact manner, then strips to her waist and approaches him. There’s no phone call from a friend here. As she reaches John, she spots the knife in his Gladstone bag, which she grabs and uses to confronts him. A struggle breaks out in which the furious woman fights so gamely that she comes close to defeating the panicky John. The whole thing is shot with the same kinetic energy that runs throughout the second half of the film, all wide-angle lenses and handheld camera, more clearly signposting where the film will later head. The first stage of the decapitation is also shown, and while lacking the grisly realism of modern prosthetics, it’s still pretty darned bloody.

As to which version is the best, well, that’s a tough call. For me, the UK release is more classily staged, shot and edited, and it works all the better for having no musical accompaniment until the moment that the woman is stabbed. Conversely, I do like the fact that the woman fights back so effectively against John in the Continental version, and that their wrestling lasts long enough to suggest that John is physically ill-equipped to be a murderer. It’s also a sequence that reverberates in the similarly shot and staged killing in the train compartment once John and Lyn move to Seaford. More annoyingly, this take on the scene is accompanied by that bloody jazz score, which makes it feel more like a dance than a fight to the death. And silly though this may sound, but so gentlemanly is Cushing as an actor that the sight of him wrestling on the floor with a half-naked woman feels a little peculiar.

The British Board of Film Censors also required changes to reels four and five to lessen the violence of two murders on the UK version, with the excised shots replaced with cut-away inserts. These scenes are intact on the US version.

An excellent 1.85:1 transfer from a 2K Sony restoration, supervised by James Owsley. The picture is sharp and detailed and has a contrast range that gets the black levels right but doesn’t batter the picture information in darker areas on screen in the process. While some of the scenes in the London-set first half have a dour, earthy look to the colour palette, it repeatedly intermittently pops to life in the shape of brightly coloured props, costumes and sets, often when Lynn is on the screen and in a positive mood (the early party scene is a good example). As soon as John and Lynn reach Seaford, however, the screen is awash with vibrant colours wherever you look, from the vivid blue of summer skies to the luminous red of a top John would probably have never have worn in the city but in which he looks perfectly happy as he joins the equally radiant Lyn in their superbly located Seaford cottage garden. The picture is clean of dust and damage and a fine film grain is visible. There are a couple of wide shots – one just before the train compartment assault – that are soft enough to almost suggest focus issues at the time of filming, but these are brief and do not impact on the scene in any significant way.

The soundtrack is DTS-HD 1.0 mono and is also in robust shape, at least within the restrictions expected for a low budget film of this age. Dialogue, effects and music are all clear and there’s no background hiss – just don’t go expecting any thunderous bass punch or glass-shattering trebles.

Those handy optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired can be activated either through the main menu or via your player’s remote control.

Audio Commentary with David Miller and Jonathan Rigby

Here, English Gothic author Jonathan Rigby teams up with Peter Cushing biographer David Miller to comment on a film that Rigby regards as an unsung classic, and while Miller tends to agree with him on many points, I did get the feeling that he’s not quite big a fan as his companion. It’s certainly described up front as a film that a lot of Cushing fans wish did not exist, and is one of two (the other was the same year’s The Blood Beast Terror) that Cushing himself later described as the worst films he was involved with. This was apparently more due the extremity of the violence than the story, which is what attracted him to the project in the first place. There’s information on the actors, the production company, the release, and the sometimes hostile critical reception, and there’s plenty of analysis of individual scenes, characters and the thrust of the narrative, all of which makes for intriguing listening. Comparisons are made to the novel, which was based on the first draft of the screenplay and thus differs in some surprisingly substantial ways to the film. It’s described by Rigby in no uncertain terms as “bloody awful,” though it does help to clarify a few of the small dangling plot threads and expand on character detail. The links to both Eyes Without a Face and Macbeth are highlighted, as is the influence of the Jack the Ripper murders, and Rigby notes that the character of Terry is “the catalyst for an already mad film to go absolutely bonkers.” A really useful an enjoyable companion to the film.

It’s worth noting that when you select this commentary on the special features menu, you’re offered the option to play it with the UK version of the film or the Continental one. For the most part, you get the same commentary on both, but during the scene that is significantly different on each – the murder of the sex worker – the commentary is specific to that version. I really admire and appreciate this attention to detail.

The Guardian Interview with Peter Cushing (71:34)

Conducted by David Castell at the National Film Theatre in London on 25 March 1986, this interview with Cushing was recorded for archival purposes and comes with the usual warning about quality, which does go up and down. But oh, the content… Although 72 years of age and claiming he is 95, Cushing has the energy and wit of a particularly entertaining 30-year-old, and at times completely throws Castell off by responding to questions in the manner of a well-rehearsed comedy routine. He’s also sharp as a tack. When Castell asks him in all seriousness, “How did you manage to get to America? Because you didn’t have much money at the period. It must have been an immense problem,” Cushing immediately comes back with a deadpan, “I swam.” Later, when questions are invited from the audience, one man begins politely with, “Excuse me, Mr. Cushing,” which prompts Cushing to give him directions to the lavatory. In between the comic moments we also get some fascinating tales about the actor’s early career, his work on stage and television (he regards his role as Winston Smith in the BBC production of 1984 as a particular highlight) and his move into features. That he still looks back at his time with Hammer with affection warmed my heart, and he even responds positively to the idea of appearing in another Hammer production should the opportunity arise. I did find myself wondering how long Indicator have been sitting on this absolute gem, presumably waiting for the right title to pair it with.

The BEHP Interview with Peter Newbrook (91:06)

Another of the exhaustively detailed interviews with filmmakers recorded as part of the British Entertainment History Project, this time with Corruption producer and cinematographer, Peter Newbrook, and conducted by Alan Lawson and Roy Fowler in February, April and May of 1995. Newbrook covers his whole career, from his early work as assistant cameraman at Warner and Ealing studios and his wartime duties, to his subsequent projects as director of photography. He has a low opinion of Michael Powell, whom he describes as very rude and opinionated, but clearly liked John Houseman, who he regarded as an excellent producer, and David Lean, with whom he worked on and off for 11 years. We get plenty of information on the formation of Titan International Films and the projects made under that company banner (Corruption doesn’t get much coverage, but Newbrook does acknowledge its financial success), and there are a few stories about the drinking culture that was so much part of the British film industry of the day. These include an interesting bit of insider info about how Osmond Borradaile, the original cinematographer on Scott of the Antarctic, fell out with director Charles Friend and ended up leaving the picture after a fist fight between them. Splendid stuff, as ever.

The following four interviews are in a sub-menu accessed by selecting Cast Interviews on the special features menu.

Phillip Manikum: The Reluctant Beatnik (14:37)

Phillip Manikum looks back at how he became a professional actor and landed his first film job in Corruption playing Georgie, a character whose role in the story I can’t discuss without another spoiler warning. He talks about being costumed and wigged for the role, working at the speed of a television crew in a tiny Isleworth studio, getting useful advice from Peter Cushing on how to play a scene, and a good deal more. His recollections about how David Lodge shaped the character of Groper offers a personal take on a story told in the commentary, particularly when he suggests that any shot featuring them both was effectively stolen by Lodge’s gurning.

What Ever Happened to Wendy Varnals? (16:09)

Former actor Wendy Varnals, who plays second-half character, Terry, looks back at how she slid into acting (her words), found fame as a youth TV presenter, and how this eventually led to what proved to be her final acting role in Corruption before she chucked it all in and moved to America. Her journey to this point is peppered with interesting titbits I would have been happy to hear more about – working for an improv group run by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, sharing a dressing room with a young Glenda Jackson – but we also get welcome info about her work on the film. She joins me in suspecting that the chase scene has been sped up, qualifying her statement with, “I couldn’t have run that fast.”

Interview with Billy Murray (13:38)

Actor Billy Murray, a now familiar face from a wide range of films and TV from Performance to EastEnders, looks back at his work on a film he would not watch by choice because he dislikes the sight of blood and is easily scared by horror movies. He talks about the direction he received from Robert Hartford-Davis, his admiration for Peter Cushing, and opines that, as mentioned above, the gang members were caricatures of what the filmmakers imagined gangs were like at the time. He recalls the accident mentioned by Phillip Manikum in his interview above, but contradicts his account by revealing that it was a staged tussle with Cushing that led to the injury, which was to his left cheek rather than the eyebrow that Manikum remembers. I genuinely winced at the news that it required 17 stitches inside his cheek and 15 outside to repair.

Interview with Jan Waters (9:08)

A 2012 interview with actor Jan Waters, who plays John’s first victim in the UK and American version of the film. She recalls being presented with what was effectively a whole new script as she was already in make-up getting ready to shoot the scene and being convinced that she couldn’t learn it all in time (prompt cards were used for the bits she didn’t have time to memorise), as well as wanting her character to die with her eyes open. She also admits to never having seen the whole film, but does recall it had rather a good story.

Stephen Laws Introduces ‘Corruption’ (7:02)

Horror novelist, Peter Cushing fan and Indicator regular, Stephen Laws, provides a largely spoiler-free overview of the film. He discusses how it came to be via the evolution of what evolved into Titan International Films, the fact that it so starkly divided opinion, and the links to Eyes Without a Face and the other films that, shall we say, took inspiration from the French classic. The novelisation gets a mention, and Laws also tells the story of how David Lodge was cast as Groper and shaped the character so similarly to how it was related in the commentary that I have to suspect it was drawn from the same reference source.

‘Laser Killer’ Opening Titles (2:42)

‘Laser Killer’? Do me a favour. Framed 4:3 and drawn from what looks like a second-generation VHS original, this is still of interest and adds to this disc’s completist feel. The new title is slapped on a black bar to obscure the original, and the fact that this was a version prepared for release in France is signalled by the added credit for ‘sous-titres’ and the French subtitled first line of dialogue.

Trailer and TV/Radio Spots

If you like trailers then you’ve definitely come to the right place, as there are plenty of them here, all of which can be played individually or sequentially with the Play All option. The quoted timings of the TV spots include the leaders – the TV spots themselves are either 60, 20 or 10 seconds long. We’re just sticklers for detail here. Original UK Trailer (1:49) likes the word ‘SHOCK!’ and it’s the first of many times you’ll hear a warning for women not to come alone to see the film. It’s madly edited, and in that sense does capture something of the film’s later insanity, and includes lots of action, including bits from the climax. Original US Trailer (2:06) favours “No woman will dare go home after seeing Corruption” and a couple of other seriously spoken gems (see the Edgar Wright trailer commentary below) and has the sound of a heartbeat running throughout. TV Spot A (1:05) assures us that “Corruption is not a woman’s picture” but is otherwise a cut-down version of the US trailer. TV Spot B (1:05) is along the same lines and just as daffy. TV Spot #1 (0:25) compresses the above into a tight 20 seconds. TV Spot #2 (0:25) is similar, but a tad more unsettling for some reason, and its second shot would count as a massive spoiler if you were given time to work out just what you were looking at. TV Spot #X (0s15) crams it all down to 10 seconds and flies by so fast you’ll barely have time to register anything you’ve seen. Radio Spot #1 (0:54) bangs on about this not being a woman’s picture and reminds us that the film is in colour. Radio Spot #2 (0:30) does roughly the same thing in half the time.

Edgar Wright Trailer Commentary (2:24)

Filmmaker Edgar Wright, in what looks like his younger days, delivers an immensely entertaining commentary for Trailers From Hell, which he kicks off with the proclamation, “I’m not going to say that Corruption is one of the greatest thrillers of all time, because it isn’t, but this is a pretty great trailer.” He reveals that it influenced the Don’t parody trailer he created for Grindhouse, is amused as hell (as I was) by the narrator wondering, “Where will the bodies turn up next? In a valise?” and reacts to the film’s sexist tagline, which warns that ’No woman will be admitted alone to see Corruption,’ by proclaiming, “What they haven’t thought about is that would any woman on their own want to see fucking Corruption?!”

There are three Image Galleries. Production Stills has a whopping 122 screens of production photos, most of which are black-and-white or colour images of scenes as they were played, but there are a couple of posed pics and a small number of behind-the-scenes shots. Promotional Materials features 63 screens of British and German lobby cards and press book pages, the front and back cover of Peter Saxon’s novelisation, what looks like a magazine article on the film titled Britain’s Monsters Must Also Be Gentlemen, plus a collection of international VHS covers and film posters. Director’s Shooting Script has 82 screens (plus an introductory title screen) of just that, complete with Robert Hartford-Davis’s handwritten annotations, the striking out of scenes and lines of dialogue that he had elected to cut, and even additional dialogue that was presumably concocted at some haste. I found this very interesting.

Booklet

An even beefier than usual Indicator booklet opens with the Corruption credits, then kicks into high gear with a smart and thoughtful essay titled Corruption, Body Parts, Nausea, and Swinging London by Laura Mayne. The Rise and Fall of Titan International Films is told through unattributed text and illustrated with a profile from the Independent Film Journal and a rather testy letter written by Robert Hartford-Davis and Peter Newbrook to The Tatler bemoaning the stagnation of the British Film Industry, the blame for which they lay on just about everyone else. An interview with Peter Newbrook, conducted by Michael Ahmed for a PhD on the films of Robert Hartford-Davis, delivers more information about the release of Corruption than its making, and goes some way to confirming my worst suspicions about how I was expected to interpret that ending. The Cast of Corruption has extracts from the US press book about the actors, but the black text on red background is something my partial colour blindness prevents me from reading. I’m sure it’s of interest. I approached Bill McGuffie and the Music of Corruption a little tentatively, given how annoying I found the score, but it’s still worth a look. More fun is Corruption is Not a Woman’s Picture!, which looks at the film’s gender-dopey marketing campaign, one that ends with the reassuring information that “there are no records of cinemas carrying out any of these stunts, or of unaccompanied women being denied admission.” As I started reading Corruption: The Novelisation, I couldn’t get the sound of Jonathan Rigby saying, “I have to tell you the novelisation was bloody awful” out of my head. Handily, several extracts are provided to allow you to judge for yourselves. I’m saying nothing. Five contemporary critical reviews have been quoted from, including the spectacularly hostile one by Penelope Mortimer for the Observer that is quoted in the commentary. It’s styled as a letter to chief censor John Trevelyan with Ms. Mortimer hoping that “the film sinks into the unpublicised oblivion that it deserves.” Ouch. The booklet is well illustrated with stills and posters.

Reviled on its released, later dismissed by its star, Corruption is the sort of film around which cult followings deserve to grow, but it also has what it takes to thoroughly irritate and even distance a portion of a modern audience. On my first viewing, my jaw kept dropping as the film progressed until I was almost tripping over it. The second time around, I thought it was a blast. This is a brilliant disc, with a boffo transfer accompanied by a barrowload of excellent special features, including a most substantial booklet. I have the review disc, but I’ll be buying the commercial release in order to own what is very much a special edition. Highly recommended, except perhaps to those above-mentioned women who wouldn’t want to go alone to see fucking Corruption in the first place.

|