Whiskey River take my mind,

Don't let her mem'ry torture me.

Whiskey River don't run dry,

You're all I've got, take care of me. |

| Whiskey River – Willie Nelson |

Regular visitors to this site will know by now that we tend to put ourselves into our reviews and approach the films we cover from a subjective viewpoint. Often this involves recalling our first exposure to, or long-standing relationship with, a particular film, director, actor, or composer, but sometimes it’s seen us draw on our own experiences as they relate to the subject of the film in question. Back in 2012, when my fellow reviewer Camus reviewed Billy Wilder’s superb study of the destructive effects of alcoholism, The Lost Weekend (1945), he began by laying out his own relationship with the demon drink to a boldly honest and self-reflective degree. Now, tasked as I am with reviewing the little discussed 1970 British film A Day at the Beach, I guess it’s my turn.

I had my alcoholic beverage somewhat later than most of my friends, who began drinking long before they were legally permitted to do so. It happened when I was 17 years old, at a party thrown by one of the older students on the two-year art course on which I was enrolled, where another of the mature students convinced me to try a Cinzano and lemonade. It doesn’t really taste like an alcoholic drink at all, he claimed. Turns out he was right. Frankly, it’s a drink I wouldn’t piss into now, but that’s beside the point. A moderately sweet cider came next and hey, I thought, I rather like this. Can I have another? By the end of the evening I was complete rat-arsed, but from that moment on there was no turning back.

Things really moved into high gear when I enrolled in film school and met the man who would become the Withnail to my Marwood, a relationship that I’ve already outlined in my review of the film that this character comparison is drawn from. You can read it by clicking here and scrolling down past the screen grab of Withnail and Marwood at the dinner table with Uncle Monty. To say that my Withnail liked to drink would be like claiming that cows are partial to the odd bit of grass. We quickly became close friends, and I found myself accompanying him on his sometimes nightly benders, heroic pub crawls that left me so drunk that I struggled to make my way back to my lodgings, where I kept a saucepan by the bed for the late night vomiting that would sometimes ensue. After I left film school, I continued to drink socially, if sometimes carelessly. Despite the distance that a relocation on my part had put between us, my friendship with Withnail remained as strong as ever, and when we did intermittently meet up in London, I’d usually end the day in a dizzying alcoholic daze. Like the Withnail of Bruce Robinson’s film, my friend would lose all inhibitions and act on foolish instinct when plastered, which more than once landed us in all sorts of trouble, and on one occasion saw us forcibly and angrily ejected from the London head office of a then well-known record label.

Occasionally, I was every bit as thoughtless as my friend. When a work colleague and I went for a beer one evening, we stayed in the pub and got so drunk that he ended crashing out at my place instead of going home. The next day, I felt the full force of the wrath of his entire family, who had spent the evening worriedly making calls to find out what had happened to him. Unlike Camus, I have had my share of sometimes spectacular hangovers, but that never seriously slowed me down, and the main reason that I restrict myself to a few glasses of wine on a Saturday evening these days is because at my age my body just won’t tolerate more. I no longer get drunk (except for a couple of times when visiting Japan, but that’s a whole different story for another day), and seem to have finally got the balance about right. Yet I still remember with crystal clarity what it was like to be almost a slave to booze and to be pissed enough to be completely irresponsible in my thinking and behaviour. So why this lengthy opening confessional? Ah, well, hopefully all will soon become clear.

A Day at the Beach may read like the most innocuous and family-friendly title, but I have little doubt that this was a deliberately ironic choice on the part of Dutch author Heere Heeresma, on whose novel – via the English translation by James Brockway – the screenplay by Roman Polanski was based. Yes, that Roman Polanski, the one who just two years previously had scored an international movie home run as the writer (from Ira Levin’s novel) and director of the urban horror masterpiece, Rosemary’s Baby. Having approached the film knowing little about its content, and thus unaware of the points of recognition that would later emerge, I was nonetheless hooked by the unforced economy of its title sequence and opening scene. It embraces the film mantra of show, don’t tell, and while there are snippets of spoken exposition, they are dropped so casually into conversation that I only recognised them as such sometime after the fact. Having started watching a particular poor low-budget horror flick the previous evening (one whose title I can’t even remember now) in which the whole plot is lazily laid out in the opening scene by the female protagonist babbling her thoughts into a digital recorder, this proved especially refreshing.

The film begins with what proves retrospectively to be a metaphoric image of a shoed foot stepping into a puddle on a rain-soaked Copenhagen street. The foot belongs to Bernie (Mark Burns), whom the camera then follows as he walks along the footpath and stops briefly to glance down at the rainwater running down a drain that he then spits into. Symbolic? Oh yes. He continues on and stops outside an apartment block, where he pauses to give a car parked outside the once over, then enters the building and leans casually on one of the doorbells. The door is answered by Melissa (Fiona Lewis), whose dressing gown, half-closed eyes and unkempt hair tell us instantly that she has just got out of bed, while her groan of “Oh no, Bernie, oh dear, no,” makes it clear that the two are not exactly bosom buddies. Bernie has a dig at her early morning appearance and mockingly claims that Carl spends too much money on her, confirming that these two are not in a relationship and that Carl is likely the name of her boyfriend or husband. Yet as Melissa wanders off to get dressed, Bernie confidently walks straight to the kitchen and opens the fridge in a move that confirms that he is no stranger to this place. As he does so, Melissa calls out from the nearby bathroom, “You’re not drunk, are you, Bernie?” The very fact that she asks this at what is clearly an early hour of the day is revealing, as is the brief pause and weary tilt of the head that Bernie gives before grabbing and swigging from a bottle of milk. He talks of an arrangement made for today that Carl is apparently aware of and that he suspects that Melissa has forgotten about, then makes his way into the dimly lit living room, where for the first time since he entered the apartment he shows signs of discomfort, emphasised by the thriller-inflected repeating rhythmic notes of Mort Shuman’s score. He sits down on the sofa, hunched forward and anxiously rubbing his knees before pushing back the objects on what is revealed to be the chairside drinks cabinet. He quickly pours out two small glasses of vodka, which he holds in his hands for a few pensive seconds before downing them both, then leaning back and reacting like an drug addict who has just scored a much needed hit, which in a sense is exactly what he is. He then replaces the glasses, closes the cabinet, rearranges the objects on its surface, and moves to a nearby chair, where the effects of his addiction are reflected in his body language and expression.

So who are Bernie and Melissa to each other? Well, that’s where things get speculatively interesting. Just as the effects of the alcohol are washing over Bernie, in runs ebullient young Winnie (Beatrice Edney), who is clearly overjoyed to see him. “Hello, Uncle Bernie!” she chirps enthusiastically, “Have you called to take me out for the day?” Bernie instantly snaps out of his malaise, swooping Winnie up into his arms and cheerfully affirming that he is. They’re then joined by the cheerless Melissa, who is now fully clothed and ready to leave. Before doing so, she dispassionately asks Bernie to finish dressing Winnie, then reminds him to shut the front door when they leave. He affirms that that he will and shoos her on her way, then intriguingly adds, “I’m glad you feel you can trust me nowadays with your table silver.” It’s a comment that prompts the departing Melissa’s gaze to momentarily falter, and us to add a few more pertinent details to their backstory. At this point the relationship may seem obvious – Bernie and Melissa are brother and sister, and despite the uneasy relationship between them, Bernie has come round to take Winnie out for the day because both of her parents are busy. After all, he’s Uncle Bernie, right? And despite his drinking problem, Uncle Bernie has agreed to take Winnie out for the day for no other reason that he enjoys spending time with his niece.

Yet what happens next seems to kick a hole in that theory. After Bernie sends Winnie off to find some trousers to cover the squeaky leg calliper that we only now have discovered that she is wearing, he ambles into Melissa’s bedroom and lies down on the bed to lovingly stroke and smell her sheets, only to then worry that it might be the side of the bed that Carl sleeps on. A new scenario thus presents itself, one in which Carl is Bernie’s brother and he married a woman that Bernie really had the hots for, or perhaps even once dated himself. But there’s also a third possibility, that Bernie and Melissa were once indeed a couple and that Winnie is the product of that union. In this scenario, their relationship ended shortly after or perhaps even before Winnie was born, and Winnie was told by Melissa that Carl is her father and that Bernie is her uncle, and in exchange for agreeing to this Bernie has been granted visitation rights. Could their breakup be what drove Bernie to drink, or was his drinking the cause of their separation? I don’t think it's dropping a serious spoiler to reveal that the film never confirms which of these scenarios is correct.

The problems start for Bernie even before he and Winnie board their train to the seaside, when he is unexpectedly confronted by burly loan shark Louis (Bertil Lauring), to whom he owes money and to whom he pleads poverty and is only able to hand a few paltry coins. One violent smack around the head later, he’s warned of the consequences if he doesn’t cough up the full amount next week. This is all witnessed by the alarmed Winnie, who loudly berates the Louis as he departs, something that loan shark pays no heed to. We soon discover that Bernie was lying to Louis and has at least some of the borrowed money on him, and the fact that he would rather take a beating than give up the funds he needs to buy more booze tells its own story.

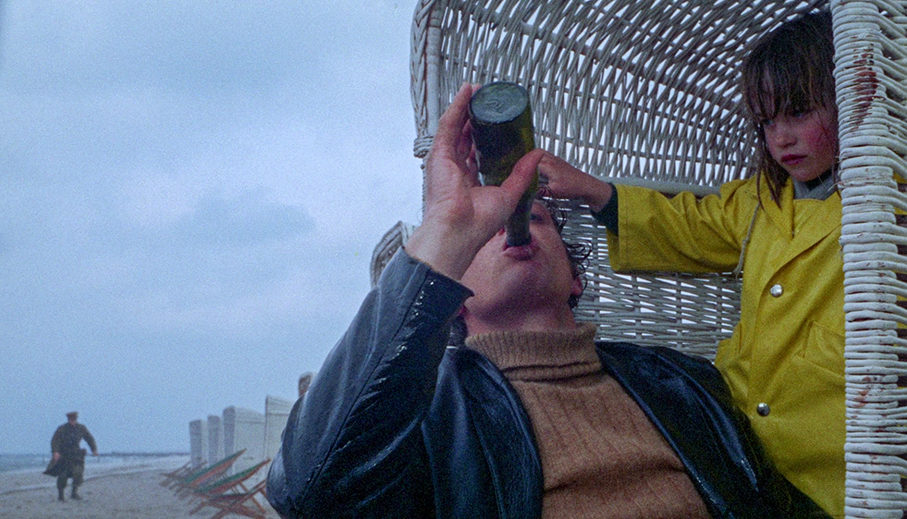

When Bernie and Winnie arrive at their seaside destination, it rains relentlessly and the beaches are empty of people, save for a pair of middle-aged gay stallholders, an overly officious seaside chair attendant (played by character actor favourite Jack MacGowran), and a mother and daughter team who run an empty seaside café (Eva Dahlbeck and Sisse Reingaard respectively). Let’s pause a second here to give those stallholders a special mention. Going into the film knowing little about it as I did, I did a serious double-take at this point, and if you want to do likewise, I’d skip to the next paragraph bypass my coverage of this disc’s special features, and avoid reading anything more about the film. One of the actors in question – Graham Stark – is named in the opening credits, but the other one isn’t, and I’d love to know the full story behind how the filmmakers managed to bag this particular actor for a small supporting role and why he elected not to use his real name in the end credits. The actor in question is none other than Peter Sellers, who by this point in his career was a well-established and celebrated comedic star. The flamboyant flirty effeminacy of Graham Stark’s character and the “A. Queen” pseudonym adopted by Sellers do date the film a little, but there are still small signs of a more progressive attitude to characters that were still being mocked in the cinema of the day. In the closing credits the two men are listed as ‘The Partners’, a term that could be applied equally to their business and their private lives, and although both come on heavily to Bernie when he tries to buy some beers for himself and a seashell for Winnie, instead of reacting with revulsion as was too often the case, he instead calmly berates Stark’s character Pipi for overplaying his gayness in a way that is upsetting his friend. Bernie’s put-downs amuse the hell out of Sellers but ultimately come across as sincerely delivered advice designed to help patch up Pipi’s fractured relationship with his partner.

The sole dramatic feature from director Simon Hesera (whose only other IMDb credit is the 1972 documentary, Ben Gurion Remembers), A Day at the Beach is less interested in traditional narrative storytelling than painting a picture of an alcoholic in the latter stages of potentially terminal decline over the course of a single day and night. For some, just that short synopsis will boot it from their watchlist, but having done my share of excessive drinking with no thought to the short or long-term consequences, more than once here I experienced real pangs of recognition. This particularly hits home when Bernie bumps into his poet friend Nicolas (Maurice Roëves), whom he steals away from his long-suffering wife Tonie (Joanna Dunham) and their young son to go on a two-man bender that Bernie easily persuades the gainfully employed Nicolas to pay for, continuing to order endless drinks for them both even after Nicholas has slipped drunkenly into unconsciousness. I can’t tell you how many times I played Nicolas to my late friend’s Bernie, and even Bernie’s reciprocated come-on to Tonie while Nicolas is unconscious or just out of sight feels uncomfortably true to form. What makes this scene all the more relatable for me is the truthful nature of Mark Burns’ performance, which captures the essence of manipulative and morality-free drunkenness with the sort of unnerving accuracy that transported me back to days that I know that I enjoyed but that I have distinctly mixed feelings about today. It’s Burns who creates the necessary connection between the audience and a central character whose self-centred thoughtless and neglectful behaviour would normally make him impossible to relate to. For some it likely will. The fact that he also appears to be a frustrated poet whose every line of dialogue has the wording and delivery of a carefully composed theatrical prose should also theoretically prove a barrier to engagement, but for some reason (I’m crediting Burns again here as strongly as Polanski’s script) this just makes him all the more fascinating to watch and listen to. Thus, under different circumstances, I’d find myself torn when it came to how to react to Bernie’s behaviour. Under different circumstances…

What gave my empathy a sharp kick in the nuts, and the person who is quickly established as the film’s unassuming moral compass is Winnie, and take it from me, you don’t have to be a parent to feel for her as Bernie becomes so wrapped up in his drinking he seems to forget she’s even in his charge, in part because he’s at his most indulgent when she is out of his sight. The performance of the then seven-year-old Beatrice Edney (the daughter of actress Sylvia Syms) is crucial here. Winningly natural, never annoyingly precocious, and most crucially of all, never judgemental, she clearly loves Bernie, and while fully aware of his problem with alcohol, she never lectures him on the damaging effect even she is aware that it is having. Although negatively impacted by the consequences of his behaviour, she nonetheless seems to accept it as an uncomfortable but inevitable aspect of their relationship, and always takes his side when he is chastised by others. Yet it’s precisely that devotion that made me want to step into the screen and smack some responsibility into Bernie. The passing of time has made his negligence feel even more reckless, as Winnie becomes tangled in fishing nets while he ploughs through beers at the beachfront café, and is left with Nicolas and Tonie’s young son in the couple’s small car for hours unattended while the two men get plastered in a nearby bar. This negligence hits a peak late in the evening when the drunken Bernie agrees to take the understandably tired Winnie home, but suggests he first call her mother to tell them that they’re on their way (frankly I’d think she’d be tearing her hair out with worry by this point). As ever, Winnie agrees, so Bernie asks her to wait where she is while he goes off to make the call, leaving her alone in the dark by a churchyard gate and heading straight to another bar to morosely continue his drinking until he is chastised by concerned locals whose flustered attention has caused Winnie even more distress.

All of this must make A Day at the Beach sound like a serious downer, and I’m not going to pretend for a second that it isn’t, but as I hope I’ve at least hinted above, it also makes for compelling, penetrating and socially conscious drama. Speaking from personal experience, its portrayal of the emotionally damaging effects of alcoholism is absolutely spot on, and I’d argue that Bernie is the very definition of the notion that character doesn’t have to be likeable to be interesting. Many, I’m sure, will find it increasingly hard to emphasise with him on any level, and I do understand and appreciate that, and that most will find his negligence in regard to Winnie infuriating or genuinely upsetting. Polanski’s complex and literate script is thoughtfully interpreted by director Simon Hesera, and he’s aided immeasurably by the downbeat mise-en-scène and Gilbert Taylor’s naturalistic but richly atmospheric cinematography. It just won’t work for some and will prove too dark for others, but some weeks after I first watched it,* I still can’t get the damned thing out of my head, and I mean that in the best of ways.

Also included alongside the restored 82 minute cut of the film discussed above is a version that has been sourced from a standard definition master that includes two minutes of additional footage. I’ll admit to not having had the time to meticulously compare the two cuts on a shot-by-shot basis, but it’s clear that the main difference occurs immediately after the opening title sequence.

In the 82-minute version, Bernie walks down a rainy street, looks over a car outside the apartment building, then enters and rings the doorbell of Melissa’s apartment. Once he is in inside and helping himself to milk from the fridge, Melissa asks from the adjacent room if he saw Carl on the way up, and Bernie tells her that he did and that he spoke to him. As we did not see this happen, and it so becomes evident learn that Bernie’s word cannot always be relied on, my assumption was that he was lying to Melissa, not only about having spoken to Carl, but also, by implication, about the arrangement he claims to have made with him to take Winnie out for the day.

All of that changed when I saw alternative cut. Here, Bernie does not head straight to Melissa’s flat after looking over the car, but instead hangs around outside the building until Carl emerges, then strides over to pester him in a way that Carl clearly regards as annoying and a little intimidating. It soon becomes evident that Bernie’s prime purpose here is to pressure the financially secure Carl for money with which to entertain Winnie for the day, something Carl initially resists but eventually gives into in order to get Bernie off his car. Carl’s dress sense and accent alone are sly indicators of his social status and financial position, and we now know why Bernie stopped to look at what turns out to have been Carl’s car before entering the apartment building, and where he got the money he keeps hidden from Louis. Despite his ever-so English accent, Carl is played by Danish actor Jørgen Kiil, whose name appears in the opening credits of both cuts of the film, despite only being mentioned by name in the 82 minute version. I don’t currently have an explanation for why this scene was cut, as it definitely adds to the film and clearly belongs there.

Teasingly, it is revealed on the disc that the version originally premiered at Cannes ran for 92 minutes before being later cut down to that 82 minute version by director Simon Hesera. While I’d love to see the longer edit, it sadly seems likely that it has lost to history.

To quote the accompanying booklet:

A Day at the Beach was scanned in 4K, restored and colour corrected at Filmfinity, London, using the original 35mm negative. Phoenix image-processing tools were used to remove many thousands of instances of dirt, eliminate scratches and other imperfections, as well as repair damaged frames. No grain management, edge enhancement or sharpening tools were employed to artificially alter the image in any way.

The naturalistic visuals and glum, rain-drenched seafronts could theoretically present quite a challenge for any film-to-digital transfer, yet as shot by master cinematographer Gilbert Taylor – who would go on to lens Frenzy for Alfred Hitchcock the following year, horror hit The Omen in 1976, and a little space opera you may have heard of called Star Wars in 1977 – the detail remains clear, the sometimes intentionally dour colour has an often attractive pastel leaning, and the contrast is expertly graded without ever compromising the film’s realist aesthetic. This is handsomely reproduced by the restoration and transfer on Indicator’s Blu-ray, particularly in the grading of the colour and contrast and the crisp definition of the image detail. There’s something about the look of the film here that I really appreciated, not least how clearly and atmospherically the rainfall is captured without resorting to the usual trick of heavy backlighting. The film grain is visible and consistent throughout and the framing is a slightly unusual 1.75:1.

The mono soundtrack is rendered here as Linear PCM 1.0. The dialogue and music are always clear, though the tonal restrictions and treble bias do result in a very slight hiss to the delivery of words containing a prominent use of the letter S. There are otherwise no signs of damage or serious wear.

The 84 minute cut was supplied to Indicator in standard definition and framed 1.33:1, which not only heavily crops the picture on both sides, but also makes small trims to the top and bottom of the frame as well. The image has been upscaled to HD for this disc, and though it inevitably falls well short of the restored 82 minute cut, it’s in far better condition than its SD origins might lead you to expect. The soundtrack is also Linear PCM 1.0 mono and subject to the same restrictions and positives as its restored companion.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available for both cuts.

Fiona Lewis: A Country Girl (6:03)

A new interview with actress Fiona Lewis, who recalls sharing a Belgravia bedsit with Jaqueline Bisset during their modelling days, and landing a bit part in the all-star 1967 comedic take on Casino Royale. She reveals that it was through Bisset that she met Roman Polanski, who cast her as Magda the Maid in his 1967 horror semi-spoof, The Fearless Vampire Killers, and suggests that he had originally planned to direct A Day at the Beach. She describes the film’s lead Mark Burns as a fun and talented guy, and director Simon Hesera as quiet and methodical, though doesn’t touch on the fact that this would be the only dramatic feature that he ever helmed.

Dancing Before the Enemy: How a Teenage Boy Fooled the Nazis and Lived (2015) (63:57)

A 2015 documentary about the wartime experiences of A Day at the Beach producer Gene Gutowski, aka Witold Bardach. It’s directed by his son, Adam Bardach, who reveals up front that his father only really opened up about his past after the cathartic experience of producing The Pianist for his friend, Roman Polanski. There’s something captivating about the understated way that Gutowski tells his frankly extraordinary story, growing up as a young Jew in Nazi occupied Poland, where he repeatedly escaped death by the skin of his teeth, at one point even having to separate from his family to stand a chance of survival. Things didn’t improve much when the Russians invaded, but as Gutowski notes, life was not pleasant or comfortable under the Soviets but it was at least not life-threatening. When the Germans returned and Jews were forced to wear armbands, Gutowski refused, getting away with it because he didn’t look Jewish and was fluent in German. The deception crashed and burned when he was turned in by a “Ukrainian son-of-a-bitch,” which landed him in the Bełżec death camp, where he narrowly escaped execution thanks to his extraordinary self-confidence and bravado. There’s so much more to what Gutowski and his family went through than what I’ve hinted at here, but that really should be for Gutowski himself to relate. His son wisely takes a back seat here, providing an aural introduction and accompanying his father to the Bełzec Death Camp Museum, where he again allows Gutowski to do the talking. The interview is illustrated with archive footage and animated photos, and there are brief interviews with Robert Kuwalek, the director of the Bełżec Museum, and Dr. Wojiech Rewerski, the son of Dr. Zenona Rewerska, who became a surrogate mother to Butowski in dangerous times. Testimonies such as this are hugely important, particularly as those who lived through these horrific events age and pass on. That said, in these increasingly disturbing times, it seems clear that too many seem to have learned nothing from history.

Michael Brooke: The Word of an Alcoholic (14:59)

The title may make this featurette sound like a confessional on the part of Eastern European cinema expert Michael Brooke, but instead he presents a fascinating and – for me, at least – educational video essay on Polish author and friend of Roman Polanski, Marek Hłasko. This includes an examination of the 1958 film The Noose [Petla], which was written by Hłasko and directed by Wojciech Has, and whose portrait of an alcoholic in decline was admired by Polanski very likely and influence on A Day at the Beach.

Behind the Camera: Gil Taylor (12:56)

Photographed, produced and directed by Richard Blanshard in 1999 for the BBC, this is a relatively brief but still worthwhile portrait of A Day at the Beach cinematographer Gilbert Taylor, who recounts some interesting technical details and anecdotes from some of the key films that he photographed. He reveals how he was able to fill in shadows in harsh desert sunlight for Ice Cold in Alex (1958), admits that despite learning a lot, it was sometimes hard to get the exact lighting he wanted on Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) due to director Stanley Kubrick questioning every aspect of his work, and tells an engaging story about being interviewed by Alfred Hitchcock for Frenzy (1972). The main focus, however, is his exemplary work on Roman Polanski’s 1965 Repulsion, about which Polanski is also interviewed and The English Patient (1996) director Anthony Minghella has some positive words to say.

Booklet

Opening with full credits for the film, this 36-page booklet then moves on to an essay on A Day at the Beach by screenwriter and lecturer Michał Oleszczyk, who traces the origins of the “poet-drunk” back to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and outlines how the story plays out in Heere Heeresma’s source novel, before turning his attention to this film adaptation. He credits much of the its success to screenwriter Polanski, and praises Mark Burns’ central performance, though I have to take serious issue with his claim that seven-year-old Beatie Edney was badly directed and doesn’t really register as Winnie. Next up is a collection of extracts from various publications reporting on the shooting of the film, one of which does provide a partial (though far from full) explanation for Peter Sellers’ cameo appearance. This is followed by articles from 1993 editions of the Los Angeles Times and the Montreal Gazette that shed some welcome light on why the film disappeared from public view for 23 years, as well as detailing director Simon Hesera’s quest to recover it. Due to the film’s limited release in France after it’s out-of-competition screening at Cannes, contemporary reviews are unsurprisingly rare, but three of them are quoted here nonetheless. Enthusiasm for anything except Polanski’s contribution is in short supply in dismissive reviews from Variety and the Chicago Tribune, but there’s praise for the performances and the film as a whole from the Edmonton Journal.

As an aside, I’ll just add that I adore the impressionistic minimalism of the poster artwork featuring the two main characters that is reproduced on the cover of Indicator’s Blu-ray. I want that on my living room wall.

From a film history perspective alone, A Day at the Beach is a fascinating rediscovery. It premiered at Cannes, had only a limited release in France, and was then shelved by distributor Paramount and remained buried in film vaults for 23 years before being hunted out by its director, whose only theatrical film this was. It has a script by Roman Polanski, whose intention to direct fell by the wayside following the murder of his wife – actress Sharon Tate – by the Charles Manson ‘family’, and it features cameos from the likes of Peter Sellers, Graham Stark and Jack MacGowran. The result is a film that I was consistently compelled by, and while I’m sure there are others who will have a similar view, I have little doubt that as many will find it a depressing slog. It’s exactly the type of film that I love to see resurrected and restored by the likes of Indicator, and if the film works as well for you as it does for me, then this disc is a must-have.

|