|

DISC 2

| The Hallelujah Handshake (1970) |

Camus |

|

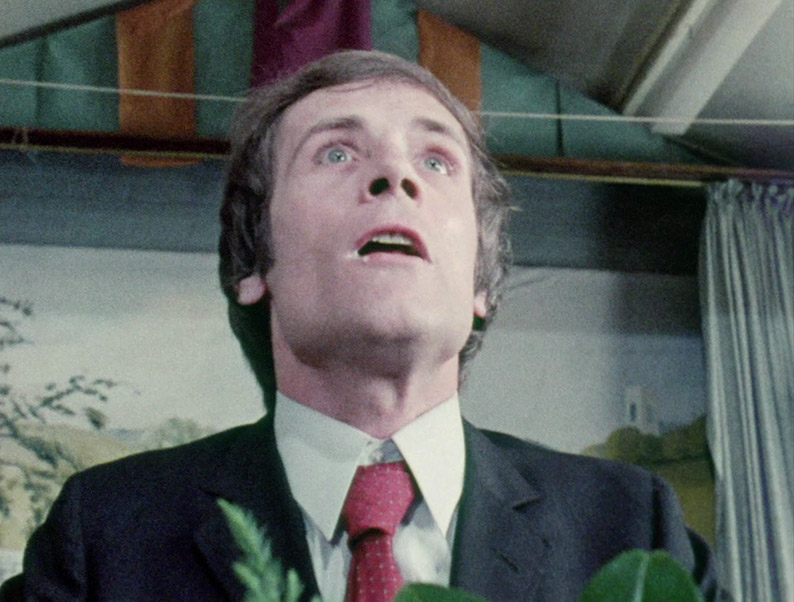

You've probably met a few 'Henry Jones's but may not have twigged; initially anonymous individuals who push loneliness away and carve out acceptance with an awkward deception built on lies and exaggeration. Some of you may have seen right through Henry and resented the attention he gets from others. Only very few will want the best for a man who's regarded as calculating, distant and possible web bait for Operation Yewtree. It's 1970 and Jimmy Saville was just getting started. Along comes Henry Jones volunteering to his local church and ingratiating himself with youth clubs and boy scouts to the degree that seems a gnat's hair from indecent. But writer Colin Welland (probably most famous for his screenplay to Chariots of Fire and his performance in Kes) is interested in getting under Henry's skin and director Clarke wants to keep us there.

With a bravura performance from Tony Calvin as Henry, The Hallelujah Handshake is a film that invites us to see the misfit in a slightly different way. He's close enough for our discomfort but not crossing a line that most would be repelled by. His 'crime' that gets him into trouble is an act of generosity and kindness seen Rashomon-style but we also sympathise with the apparent victims of his deceit, the ordinary parishioners who are, to a fault, 'nice, normal' human beings. Clarke evokes an audio trick of having the characters voice their thoughts while they are supposed to be praying or singing hymns. It's a radical departure stylistically from what seems like a standard 'Play For Today' but for all its dated aspects, it's terrifically entertaining and does not outstay its welcome at all.

| To Encourage the Others (1972) |

Slarek |

|

If the name Derek Bentley means nothing to you then it's perhaps unsurprising – it belongs to a different and, one would like to think, less enlightened age where state sanctioned execution was still the ultimate punishment for those found guilty of what society deemed to be the more heinous crimes. One of the principal problems with this ultimate penalty is that if you execute the wrong person on the basis of a poorly argued defence, a biased judge or jury, vindictive or dishonest witnesses, or any number of other legal quirks, there's no going back and putting things right later. And mistakes did happen. Posthumous pardons are all very well, but unless science finds a way of reviving the dead and repairing the bones or organs damaged in the process, the state is ultimately guilty of the very crime the victim was wrongly executed for, and given the mental torture they and their families and friends will have suffered up to and during their execution, a good deal worse. If you take an innocent life, we were told, you should be prepared to pay the ultimate price, but when the state does likewise, who is put on trial and executed for their killing? Then again, who should be? The judge? The prosecuting council? A randomly selected member of the jury? Mistakes do unfortunately get made, we are told, but how strongly would you cling to that suspect slice of reassurance if it were your son or daughter facing execution for a crime they did not commit?

In November of 1952, 19-year-old Derek Bentley was charged with the murder of a policeman during a botched robbery attempt with his friend, the 16-year-old Christopher Craig. Certain facts are beyond dispute. Police constable Sidney Miles was killed and Bentley was definitely at the scene. But Bentley was under arrest when the fatal shot was fired and at no point during the robbery did he fire or even carry a gun. The weapons that he did have were given to him by Craig, and he claims not to have even realised that Craig was carrying a gun until he showed it to him that night. But here's the thing. Being just sixteen years old, Craig was too young to be sentenced to death, and thus due to a quirk in English law at the time, Bentley was effectively executed in his place.

Being primarily a studio-bound courtroom drama, with locational recreations of the shooting and its build-up employed to support or call into question witness statements (a technique later refined to perfection by Errol Morris in The Thin Blue Line, another example of the wrong man being sentenced to death for the murder of a policeman), this may seem a stylistically atypical Clarke work. But by subtly siding with the underdog, directly challenging the establishment view of events and effectively accusing senior authority figures of bias, deception and wrongful death at a time when TV didn't tend to do that, To Encourage the Others is every inch an Alan Clarke film.

From a screenplay born from writer David Yallop's anger at what had happened to Bentley, the film never sensationalises or sermonises, instead presenting facts and witness statements in an even-handed manner that allows them, as well as what we can draw from either, to speak for themselves. The more troublesome aspects of the handling of the case are outlined in sober, Peter Watkins-style voice-over, and Clarke allows the prosecution witnesses to present their case without openly calling their credibility into question. Only the sometimes obstructive words and actions of Lord Chief Justice Godard are openly called into question by how they play out on screen, but since these are a matter of record and the film itself was checked by several lawyers before transmission, we can presume there is a degree of accuracy to this portrayal.

There is, I should note, one surprising omission here. One of the key arguments of the case centred around Bentley's call to Craig to "Let him have it" just before the shooting of constable Miles. The prosecution claimed Bentley was urging Craig to shoot the policeman, whereas the defence claimed he was trying to persuade Craig to hand over the gun following Detective Sergeant Frederick Fairfax's attempts to convince him to give himself up. This disputed phrase even became the title of Peter Medak's 1991 feature film interpretation of the same story. Here there is a clear inference in the recreations of the lead-up to the shooting that Bentley was cooperating with Fairfax in trying to convince Craig to quit firing the gun and hand himself in – immediately previous to the contentious call, Fairfax had asked Craig to "Hand over the gun, lad" – but in the courtroom scenes here this argument gets no coverage.

But the story still makes for riveting and ultimately saddening viewing. Both Charles Bolton and Billy Hamon – previous best known for supporting roles in school-set TV comedy series Please Sir! – impress as Bentley and Craig, and the supporting cast are universally strong, with Roland Culver's portrayal of the pompously biased Lord Goddard an appropriately infuriating highlight. Yallop's thoughtfully structured screenplay, coupled with Clarke's matter-of-fact handling of the courtroom scenes and small but effective flourishes in the recreation of the crime, allow the contradictions that cast serious doubt on notion idea that justice has been in any way served to get under your skin and build to a point where a blend of disbelief and outrage is the only logical response.

The Hallelujah Handshake was shot on 16mm film, and has a similar look and feel to Sovereign's Company, with visible grain, a most reasonable level of detail and no trace of dust or damage. Occasionally the image feels a little bright, but this appears to have been deliberate. The colour reproduction is rather good, though not as vibrant as it is in the later films. The soundtrack is free of hiss or damage and the dialogue is clear, albeit with a treble bias.

To Encourage the Others was shot on analogue video, partly in the studio and partly on location. The courtroom scenes are in excellent shape, displaying a surprising sharpness and level of picture detail, solidly rendered colour (the red of the judge's robe is vividly captured) and a very well judged contrast range. The exterior rooftop scenes have a harsher feel due to the high key lighting and the narrow contrast ratio of analogue video, but detail is still good. The inevitable slight treble bias to the soundtrack is not an issue when the dialogue is as clearly rendered as it is here.

David Leland Introduction for To Encourage the Others (2:33)

One of several brief introductions to Clarke's work that were originally shown as part of a season of his films screened on BBC2 to mark the first anniversary of his death, the primary purpose of this intro is to set up the season as a whole, which is followed by a brief overview of To Encourage the Others.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 2) (13:33)

Part 2 of the new documentary on Clarke picks up where Part 1 left off on Clarke's early TV career, with particular focus on the almost obsessive nature of his approach to directing, where he would exude a casual air but be meticulous in his planning and his attention to detail. Surprisingly, The Hallelujah Handshake doesn't even get a mention here, with the second half focused exclusively on the production and potential controversy of To Encourage the Others. My favourite quote about this comes its writer, David Yallop, who recalls a conversation he had with journalist Peter Wldeblood: "He said, 'This will send the entire nation to bed absolutely depressed'. I said, 'I hope so'. He said, 'But my job is to send them to bed happy so they get up and work'. I thought, 'Huxley's world is with us, it's Brave New World'."

DISC 3

| Under the Age (1972) |

Slarek |

|

The laddish Mike and Jack stumble out of the rain into an empty Liverpool pub whose gay barman Susie is preoccupied with putting on his makeup. Inevitably, they take the piss, but Susie has clearly heard it all before and has no trouble holding his own, and even takes a bit of a shine to Mike. Slowly and reluctantly polishing the end of the counter is a young man known simply as The Boy, who occasionally speaks but appears to be very much under Susie's thumb. When young and lively Sandra and Alice run in out of the rain and order drinks, Susie refuses to serve them because they are under the legal age, but Mike and Jack take an immediate and lascivious interest in these new arrivals.

Under the Age is the sort of gone-forever TV play that's more interested in its characters and how they interact than spinning a yarn in the traditional sense, an offbeat slice of life that drops into a narrative that feels like it's been already been running for some time and will continue long after the final credits roll. It'll come as no surprise that Susie is the nucleus around which the drama revolves, and at a time when you'll find LGBT characters in everything from Coronation Street to Fear the Walking Dead, it's easy to forget how rare they once were in British television drama, unless outrageously camped up and played for broad laughs, so to find one as rounded and strong willed as Susie in a TV play from 1972 is almost a shock to the system. That's not to say Susie is particularly likeable or sympathetic, but he's definitely interesting, and the mere fact that he is able to give as good as he gets when faced with Mike and Jack's laddish mockery (which itself doesn't always follow the expected path) would have been something to celebrate on its original screening and still warms the heart today.

It's not hard to see what attracted Clarke to this project, and once again his casting choices serve him well. Jack and Mike are played by Stephen Bent and a young Michael Angelis in his second TV role, a good ten years before he became a household face in Boys from the Blackstuff, while Susie is played with gruff authority by Michael's brother Paul (you'd be pushed to spot the family resemblance here). David Lincoln also makes his mark in a quiet way as The Boy, hovering tantalisingly on the periphery and intermittently breaking out from under Susie's control to chip in to the conversation. An intriguing work whose attraction lies solely in its characters and their interplay, it's the sort of left-field drama I can't even imagine being pitched to the TV execs of today.

| |

"I think all of us, no matter what our background, we've all known a subnormal guy or a backward guy, maybe someone at school who wasn't quite right… But the first draft was focused on the boy, his mate Gordon. Then Al said 'Why don't you write about the guy, move the emphasis on to Horace?'" |

| |

Writer, Roy Minton |

Horace drew the short straw genetically speaking. Now in his early thirties, Horace is – what was in the parlance in 1972? – mentally retarded. I'm really not sure how we describe such unfortunates these days but the stigmas don't pack anything like the punch they carried forty-four years ago but perhaps that's my wishful thinking. But Horace is also diabetic needing daily insulin shots. His mother has urged him to keep himself to himself, advice given out of love and an attempt to keep her son uncut by the sharper edges of life when he's clearly at a disadvantage. Horace, regardless of his disabilities, is desperate for human contact that's not necessarily his mother or dependent neighbours. In an attempt to ingratiate himself with people he meets, he forms the rather simplistic impression that because he buys 'jokes' from the joke shop at which he works, people will find them amusing and therefore will like him. Most sane people know that there are very few things unfunnier than a manufactured 'joke' to be sold in a joke shop.

The whole idea of a joke shop these days is deeply anachronistic and faintly ridiculous but given this rather harsh critique, I have to mention that the most sustained period of hysterical laughter I have ever experienced was at a government office cafeteria looking through the smoky windows at the employees passing by in a corridor. We'd deposited a fake dog pooh in the centre of the walkway and what was prompting this hysteria (I know, I know but I still smile thinking of it) were the contortions of human bodies seeing late and avoiding something they can't quite believe is there. Twenty or thirty people passed by the offensive object and not one attempted to pick it up. So maybe there's hope for Horace.

Twenty years his junior, Gordon Blackett is an unloved schoolboy, physically abused by a mother whose overbearing self-interest lies at the heart of her character. Imaginative but isolated at school, Gordon wears a makeshift wizard's cape to protect him from other people and evil and prefers to wear it at all times. This doesn't endear him to the school's rigid authority figures. One night Gordon overhears his mother talking to her current beau about moving from the area and scared of that particular future, Gordon teams up with Horace running away from the hand that life has dealt them. Once Horace takes a tentative nibble at a chocolate biscuit, we know the two of this decidedly odd couple are not going to last long on the road by themselves. While Horace and Gordon's friendship is based on little more than Horace promising to show Gordon something in which he may have a fleeting interest, their interactions have an innocence and sweetness to them which (thank goodness) never make you concerned for Gordon despite Horace being decades older. His mental disability has softened any threat as well as his inherent character.

Clarke doesn't employ incidental, dramatic or theme music very often. It's just not a good fit with the kind of drama he specialises in. That said, there is a main theme in Horace and it manages to repeat itself with enough regularity that it becomes a little wearing and if it's supposed to be a theme for Horace himself, it's a little odd. In possibly a television first, this TV film inspired a spin off series a decade later, arguably the first to feature a person with a disability as the main character. It shared the writer Roy Minton (famous for Clarke's Scum), the star Barry Jackson, and a few of the other actors from the film. Clarke is still in desperate need of a Steadicam…

Under the Age was shot in the studio on colour analogue video. The colour rendition is generally good and the contrast pleasing, though not quite as punchy as on many of the other studio-shot plays, and the black levels are not quite there. No other issues, though. The clear soundtrack with its requisite slight treble lean is free of damage and noise – what sounds at first like background hiss is actually the sound effect of outside rain.

Horace was shot on 16mm film and displays a sometimes earthy hue that occasionally strengthens, but has a good level of detail and less prominent grain than on the previous film titles. Once again, all dust and damage has been cleaned up. The sound is also clear with no issues.

Alan Clarke: Out of His Own Light (Part 3) (9:12)

"By and large, if you wanted to make serious, intelligent, thoughtful, passionate, committed films, then in the 70s and 80s you did them on television," says David Hare during an opening montage of interviews about how much Clarke enjoyed making films and how committed he was to them. Paul Greengrass and David Yallop lament the passing of a time when single television plays were regularly commissioned, and Stephen Frears brought cheer to my day with the claim that "the good thing about the BBC in those days is that they employed people who bit the hands that fed them,"

then describing the corporation as "an organisation that seemed to encourage dissent." Roy Minton also chips in about Horace, but there’s nothing specific on Under the Age.

|