"An audience is never wrong. An individual member of it may be an imbecile,

but a thousand imbeciles together in the dark – that is critical genius." |

The Viennese Pixie, aka director, Billy Wilder

(hardly a pixie at 5 foot 11 inches) |

The great Billy Wilder's oeuvre was as eclectic as any writer/director's was during an equivalent time span in Hollywood's Golden Age. Like Kubrick, when Wilder turned his hand to a genre, the resulting movie ended up near the top of its heap. Like John Ford, he regarded himself to be a simple entertainer but Wilder, again like Ford, was significantly more than that. He was an artist by accident and directed some of classic Hollywood's best loved and best known movies. He would have directed Schindler's List but deferred to Spielberg believing himself to be too old and too close to the subject; quite a few of his relatives were murdered at German concentration camps, his mother included. So, given his astounding body of work, it wasn't a bad Hollywood career for a kid from what was then Austria-Hungary.

If there is one Hollywood classic movie that defines the very essence of film noir then it's Wilder's Double Indemnity. Unknown to me at the time of writing, this is, in essence, the first line of the documentary accompanying the feature. Referring to a real life actual book for the first time in what feels like a decade, I find this definition of film noir from Ephraim Katz's well-respected and hugely informative International Film Encyclopaedia...

"A term coined by French critics to describe a type of film characterised by its dark, somber (sic) tone and cynical, pessimistic mood."

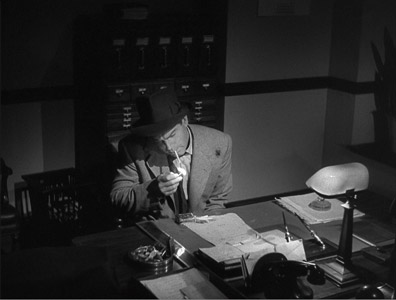

Let's add to that the sometimes literal interpretation; there are so much more black areas and shadows than in conventional movies and they are often contained in expressionistic frames, images meant to reveal a character's innermost feelings. Rarely are we presented with characters in natural and/or realistic settings without the shadows saying something about their states of mind. Light filters in through blinds (a particular favourite) stamping on characters the threat of 'behind bars' in wonderfully subtle ways. John Seitz's glorious photography almost writes the chiaroscuro rulebook for other noirs to follow.

Double Indemnity was made in 1943 so it butted up against the ludicrous censorial wall that was The Hays Code. If you read what was not permissible in movies according to this religious minded zealot, it's a miracle any film got passed at all. Wily directors sought and found many ways to insinuate what could not be portrayed and to 'show' or suggest certain no-no's was like a game of chess played between a staunch Presbyterian and a movie-making Libertarian. No Pawn was safe. Wilder was making a movie about a man who so desired a woman, he was willing to commit murder; hard to show that cinematically given what was forbidden by the code. So Wilder played a little game with the audience and shot ambiguous scenes that invited multiple interpretations. The most famous in the movie is the sofa segue, where we leave the soon-to-be murderous pair entwined on a couch tracking backwards and cross dissolving to an injured MacMurray as he continues his narration. When we return to the couch, she's applying lipstick and he's doing what everybody seemed to do in the movies after rampant sex; smoking a cigarette.

It's Los Angeles in the late 30s. Insurance man Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) visits a client whose automobile coverage is about to expire. Bluffing his way into the house, he finds his client's wife, Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), wrapped in a towel looking down on him. Let's leave the wig aside for the moment but simply confirm that sparks seriously begin to fly. She's coy but interested; he's verbally trigger-pulling, flirting on full power. The dialogue is a tango (the dance not the drink though there is significant fizz involved), a swift flurry of play and counter play. Yes, the skill and dexterity of the rat-a-tat chat are not exactly believable coming out of anyone's mouths but in this context it's perfect and eminently quotable. How's this for an exchange?

| Phyllis: |

My husband. You were anxious to talk to him weren't you? |

| Walter: |

Yeah, I was, but I'm sort of getting over the idea, if you know what I mean. |

| Phyllis: |

There's a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff. Forty-five miles an hour. |

| Walter: |

How fast was I going, officer? |

| Phyllis: |

I'd say around ninety. |

| Walter: |

Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket. |

| Phyllis: |

Suppose I let you off with a warning this time. |

| Walter: |

Suppose it doesn't take. |

| Phyllis: |

Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles. |

| Walter: |

Suppose I burst out crying and put my head on your shoulder. |

| Phyllis: |

Suppose you try putting it on my husband's shoulder. |

| Walter: |

That tears it. |

No human being has probably ever had such a wonderful verbal tennis match like this because most people don't have Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder to write their dialogue (more's the pity). Not a word of that exchange is in the source short novel. Kudos to James M. Cain for the original idea but the dialogue's all Chandler/Wilder. Stanwyck visits MacMurray later that evening and the plot to stage her husband's death begins. Being in the insurance business, MacMurray cooks up a plan in order to pull the wool over his colleague's eyes (Keyes, played by the great Edward G. Robinson). The murder itself is committed off screen but in true 'less is more' fashion, the revulsion we feel as it happens is etched on the cold, mirthless face of Barbara Stanwyck as she drives, her husband, soon to be dead, riding shotgun. These are desperately unlikeable characters and it's all the more glorious for that. Once the deed is done, the two protagonists spectacularly unravel and fall apart until the inevitable but also shocking dénouement. Let's just say there are tears before bedtime.

Raymond Chandler, I was stunned to find out from the commentary, was English (pinch of salt required – see review of the commentary in the Extras). He was so synonymous with hardboiled detective fiction just ripe for the film noir treatment, he gained a reputation for himself that had a curiously negative effect on his character. You read his fiction and then meet the man and both don't connect at all. Chandler was a short, fastidious, bespectacled soul who suffered from depression and alcoholism. He was about as far from the anti-heroes he created as it was possible to be. Chandler and Wilder wrote Double Indemnity together in a thick cloud of mutual animosity. I hate to put any evidence on the table that suggests great art must come from suffering or any bad behaviour of any kind but it's well documented that writer and co-writer/director did not get on at all. This relationship reached heights of comic surrealism as Chandler found so many aspects of Wilder's character intolerable. Chandler complained about Wilder's constant wearing of a hat giving Chandler the anxious impression that his writing partner was always about to leave... Whatever the facts of the relationship, the fruit it bore is luscious, ripe and overloaded with sin.

Double Indemnity was all but remade in 1981 as Body Heat by Lawrence Kasdan and in some ways it explicitly shows what Indemnity could not even hint at – the graphic lust. The power of that lust is more vividly and erotically brought to life on screen and William Hurt and Kathleen Turner totally convince as co-murderers. It remains a favourite of mine and introduced a young actor who managed to give Hurt a run for his thespian salary, Mickey Rourke. But there is no outside help sought in Wilder's masterpiece. The two lovers scheme and go it alone. MacMurray knows that he works with the insurance agency's version of Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, a man who can spot a phoney insurance claim a mile away by virtue of his intuition or gut feeling known to Robinson as his 'little man'. MacMurray knows that the murder will have to be perfect to fool his colleague who incidentally played a Nazi hunter in Orson Welles's The Stranger.

I must single out Fred MacMurray who gives a career best performance. His casting in 1943 was the equivalent of casting an English Etonian known for playing idiots and upper class goons as a mercilessly iconoclastic and curmudgeonly American medical genius (with a limp). Only by giving Hugh Laurie a role like Gregory House could the actor reveal hidden depths of skill and characterisation. MacMurray was a safe actor not given to roles so dark and dangerous so his casting was a revelation. He never revisited the shadows of noir again and found the rest of his career playing in Disney knockabouts and safe TV shows. It seems Stanwyck was poured into the femme fatale mould from birth. Not conventionally attractive or busty as many of her contemporaries, she nevertheless possesses a spirit of quiet ruthlessness that made her perfect as the object of MacMurray's lust. Robinson's Keyes displays the exact amount of professional expertise and affection for MacMurray and the ending (and last line) of the movie is enormously moving. It's a more than welcome piece of humanity, an emotional note that is so surprising given the characters on offer that it's more moving for that. And it also showcases the delicious double irony of the delivered line "I love you too..." from one man to another. This is great stuff and makes Double Indemnity the epitome of what's meant by the cliché "They don't make 'em like they used to..." It's a real classic for many damn fine reasons.

Presented in its original Academy 1.37:1 ratio, Double Indemnity looks cracking. The print scanned is remarkably free of dirt and scratches. The contrast ratio is suitably wide ranging for the quintessential 'Noir' and there is intentional softening on a few close ups of Stanwyck (much the norm in the 40s, women were shot very differently to men). Check out the angelic glow around her match in one particular shot. The grain is not evident at the optimum viewing distance. If there is a picture issue it's the ever so slight strobing that is visible behind Fred MacMurray while he starts his recorded confession in his office. This occurs a few times throughout the rest of the movie. It's very subtle but it is there. It's mentioned as a problem in the enclosed booklet but it doesn't detract.

The original Mono sound is clear and surprisingly free from hiss rendered in DTS-HD Master Audio.

There are optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing-impaired

Audio Commentary by film historian Nick Redman and screenwriter Lem Dobbs

Unlike the explosive and difficult pairing of Chandler and Wilder, Redman and Dobbs make an excellent partnership for a terrific commentary. It is very rarely scene-specific but does sparkle because of Dobbs' personal connection to Wilder himself. The commentary is more of a Q & A with Dobbs at the forefront but Redman's contributions are solid and coax some great answers from Dobbs. They define Film Noir (hardly unexpected) and throw out a few gems early on, one of which I was flabbergasted at. Gosh, Raymond Chandler was a Brit! Yes, I knew about the raging alcoholism but it never occurred to me that he was British. Well, of a sort. If Wikipedia is to be trusted, he was naturalized as a British Citizen when he was nineteen despite being born in Chicago. So technically he wasn't British and was only in the UK for five years… That doesn't sound like 'being a Brit' to me.

Double Indemnity was shot at the height of World War II and it's suggested by Dobbs that the timestamp on the movie (1938) is a deliberate way to stop the audience asking awkward questions – why isn't MacMurray in uniform etc.? Dobbs mentions Body Heat and Wilder's rather odd idea that his movie was a documentary version of M of all movies. That's not an easy notion to take on board. This was composer Miklos Rozsa's first of his film noirs and the Paramount music supervisor hated the dissonant new, darker sound but the Head of Paramount loved it. The pair cover the apparent 'death' of cinema, the time when the European influx of talent was cut off (doesn't say a great deal about homegrown talent) and the fact that Billy Wilder's stars were transformed by taking the Wilder part. William Holden's screen persona was set at Sunset Boulevard. He started his career as a pretty boy but soon transformed (after Sunset Boulevard) into a resigned and hardboiled cynic. This is a very informative commentary but, as I mentioned, it is rarely scene specific (my only small gripe).

1950 Lux Radio Theater adaptation starring Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck (30' 01")

Back in the 40s, Hollywood didn't have inverse pyramid marketing (as I made that term up, I'm not surprised it didn't). The studios didn't make a tent pole movie and then squeeze it dry (soundtracks, related songs, computer games, TV specials, branded toys and collectibles, ad infinitum) but they did distribute the drama to other markets particularly if movies were successful. Instead of getting an editor to cut a 30 minute version of Double Indemnity from original audio tracks, the principal cast (minus Robinson) is rounded up and re-perform a truncated radio version of their movie. Does it work? Hard to tell as I know the film version so well – no narrative surprises and I'm not sure how 'Radio Noir' could exist bereft of its 'Noir'ity. Before home video, the only way you could re-experience a movie was to hope it was re-released (unusual unless it was a Disney movie. Certain titles were famously re-distributed every seven years). Another way of getting your fix is to reimagine the movie from an audio version. It's very different (it's 30 minutes, of course it's different) but the differences are part of its charm. It can't compete with the real thing but as a reminder, it's pretty spot on.

Original Theatrical Trailer (2' 15")

"It's MURDER!" Typical for its day, a lurid and surprisingly revealing two minutes with one very unintentional cut (a cross dissolve actually) the effect of which must have occurred to someone. Neff is admitting the crime and says "I killed him for money and a woman…" at which case we dissolve through to Neff and the distinctly unglamorous and dumpy housekeeper of the Dietrichson household (Betty Farrington as Nettie). Sure, Stanwyck's the next shot but for a glorious moment, another Double Indemnity loomed up from the trailer, a classic film of Fred MacMurray killing for the love of a conventionally unattractive (and overweight) femme fatale. Now that would have been a harder sell (but no less interesting for that).

Shadows of Suspense — a 2006 documentary featuring film historians, directors, and authors discussing the making of Double Indemnity (37' 57")

A neat little accompaniment to the feature, this standard definition talking head documentary gives us all the gen surrounding the film's production. Using the opening and closing blinds as the film's central visual motif, the documentary is both revealing and informative. My one regret is finding out what seems to be utterly obvious to everyone both on the production at the time and discussed after the fact. Yes, it's Stanwyck's 'George Washington' blond wig. Of course, as a teenager I wouldn't have noticed it at all. Now, whenever I see Phyllis Dietrichson, part of me sees that damn hairpiece as a separate character. Distracting, to say the least.

Booklet – 36 pages

This features:

- A 1976 interview with Billy Wilder;

- An extract from a 1976 interview with James M. Cain comparing his original serial with Wilder's film adaptation;

- Documentation of novelist and Double Indemnity co-screenwriter Raymond Chandler's attitude toward working within the Hollywood studio system;

- An extract from the original screenplay depicting the excised "death chamber" ending;

- A note on the restoration;

- Rare archival imagery

Another little triumph with some great behind the scenes stills and relevant and hugely entertaining interviews and articles. There's a slight misprint or mis-label on page 18. I can't prove the compiler of the booklet looked at the still of the leads with Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers) signing his life away and any of Raymond Chandler and reasoned they were the same man but I can easily believe how the mix up occurred. Both men are wearing very similar glasses and Powers has a pen in his hand (don't writers use pens?) Anyhow, I'm pretty sure that's not Chandler on page 18 even though it says it is. The screenplay extract of the deleted final gas chamber scene is suitably shocking given that, at the time of shooting, the concentration camp gas chambers were doing their ugly work. In the Wilder interview, he mentions Fritz Lang's extraordinary M as an influence - unsurprising and very apt. But it's the stills that do it for me. Seeing something so familiar from an unfamiliar angle always gives me a little frisson of pleasure.

Isolated music and effects track

Again, I would like to hold a convention for all those that take advantage of this curious extra feature and see if I could fill a telephone booth…

Double Indemnity is a classic in the real non-Disney denotative sense of the word. It has a great story, terrific performances and unfussy direction. It's literally and metaphorically dark and features the actions of two highly immoral people in a tale of murder and double cross. It's bloody marvellous and Eureka has done it proud.

|