|

For a good many years now I’ve championed the animated short film as the highest expression of film as art. Often the product of an individual artist’s vision and untainted by the pressures of commercialism, it combines the disciplines of film, drawing, painting, design, sculpture and modelmaking to sometimes startling and astonishing effect. I’m fairly sure that I first fell in love with the medium in the 1980s and 90s, when a rich range of animated shorts were screened by Channel 4 along with revealing documentaries about the animators themselves, notably in the channel’s sorely missed 4Mations strand. I can’t say for sure if there was one specific film that first sparked my fascination and suspect that the honour was shared by an illustrious few. Titles I can instantly recall without having to research anything more than their year of production include David Anderson’s Deadsy (1990), Geoff Dunbar’s Ubu (1978), Andrew McEwan’s Toxic (1990), Paul Berry’s The Sandman (1991), the Quay Brothers’ Street of Crocodiles (1986), Jan Svankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue (1983), Richard Goleszowski’s Ident (1990), Clive Walley’s And Now, You (1990), and Raoul Servais’ Harpya (1979). And then there was Tango, a 1981 film by Polish animator Zbigniew Rybczynski’s that won the Academy Award for Best Short Animated Film, a work whose complexity of planning and execution genuinely blew me away. My admiration for Rybczynski was further boosted by a documentary commissioned by Channel 4 to accompany its screenings of Tango and the 1990 The Orchestra. This included tantalising extracts from several of Rybczynski’s short films and provided a peek behind the scenes at his working methods and his experiments with the then new video technology.

Sadly for me, 4Mations was wound up in 1998, and these bold, adventurous and sometimes challenging animated shorts became harder to easily see. As a wider range of feature films were made available with the widespread adoption of DVD, my attention shifted to watching and writing about these instead, and the VHS tapes onto which I had copied so many animated shorts from the Channel 4 days sat unwatched on shelves for years, shelves that would soon be cleared to make way for the ever-mounting collection of discs. My enthusiasm for the animated short was reignited in 2006 with the release of The Quay Brothers Short Films 1979-2003, and again in 2007 by Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films, both on BFI DVD and both exemplary products. My knowledge of Polish animation was also expanded just a little in 2014 with the release of Arrow Video’s superb Walerian Borowczyk Short Films and Animation Blu-ray, about which I was also able to talk to Daniel Bird, the driving force behind the successful efforts to retore these films.

By now I was aware of the work of two Polish animators, but what about the others?

Cue the fine people at Radiance Films and their announcement of a two-disc Blu-ray set titled Essential Polish Animation. Was I excited? Uh, yeah, just a weeny bit, especially when I looked down the list of the 27 short films included in this set and realised that I had only seen one of them. Of course, the film in question was Tango, and the prospect of having an HD copy of a film that I had admired for so long but previously owned only on second generation SD video would have been motivation enough for me to rush out and buy this set.

It will come as no surprise to site regulars that instead of providing an overview of the set I’ve elected to cover each film individually, which is why this review has taken as long as it has to complete. The length of my coverage of the specific films varies quite a bit, but just because I’ve written fewer words about one film than another, it doesn’t mean I hold it in a lower regard, it’s just how the words poured out of my addled brain after watching it at least twice. That approach was flipped on its head when it came to the commentaries, as instead of covering them individually in my usual manner, I’ve elected to discuss them as a whole, the reason for which I’ve outlined briefly in the appropriate section of the special features. As ever, I’ll be looking at the films in the order they appear on the two discs in this set and have placed them under the headers in which they are listed on the disc menus.

BANNER OF YOUTH [SZTANDAR MLODYCH] (1957)

A vibrantly energetic and kaleidoscopic collage of live action newsreel clips and found footage, blended with abstract animation created by drawing directly on the film in the manner of genre pioneers Len Lye and Norman McLaren. Driven along at breakneck pace by a lively jazz soundtrack, it was the work of former graphic artists Jan Lenica and our old friend Walerian Borowczyk, being designed as a promotional film for the Communist daily newspaper Sztandar mlodych and targeted at the post Stalinist youth market. Deconstructing the underlying message here would make for a media studies exercise and half, as cyclists race, vehicles crash, boxers trade punches, buildings burn, soldiers march, a tornado wreaks havoc, rockets launch, musicians play, and people dance. And that’s just a sampling of the lively cornucopia of imagery here.

LOVE REQUITED [NAGRODZONE UCZUCIE] (1958)

The lonely and ordinary Mr. Ludwik dreams of finding true love and heads off on holiday in search of the perfect partner in this second collaboration between Borowczyk and Lenica. It tells its relatively straightforward story exclusively through the paintings of self-taught amateur artist Jan Płaskociński, which are brought to life not by animating the images themselves but through the creative and witty use of framing, rostrum camera movement and editing. Thus, the excitement of Ludwik’s journey to his holiday destination is suggested by various lightning-fast edits (courtesy of Krystyna Rutkowska) of a painting of a train coupled with whip-pans across it to suggest the vehicle’s speed. A similar use of rapid editing and framing is used to imply Ludwik’s fascination with certain body parts of a group of female basketball players, while the image of a troupe of interlocked female acrobats is rotated in both directions to suggest the orchestrated tumbles of their act. It’s all set to a score by the Brass Band of the Warsaw Municipal Gasworks, which provides an musical link between working class Poland and its Northern UK equivalent.

THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD [ZMIANA WARTY](1959)

As the town clock (represented here by a pocket watch) strikes 12, the palace guard parade before the watching royal princess, and a single, slightly bumbling soldier takes the evening watch while his comrades return to the barracks to sleep. The princess is quite taken with this soldier as he seems to be with her, but giving in to their mutual passion comes at a heavy price.

Co-directed by partners Halina Bielinska and Włodzimierz Haupe, the real charm of this Cannes award-winning stop-motion short lies in its design and execution, with the town constructed as a white wire frame representation of child’s drawing and the characters represented by appropriately decorated matchboxes, with each of the guards holding a single match as a rifle and boxes sliding open to emit shouts, sighs and snores. The metaphors are out in the open when the heat of passion causes the soldier and the princess to spontaneously combust, and feel free to interpret what immediately follows as you please.

NEW JANKO THE MUSICIAN [NOWY JANKO MUZYKANT] (1961)

Solitary farmer Janko is an amateur musician who dreams of concert glory but whose off-key playing infuriates the local populace but unexpectedly delights more heavenly creatures.

The first solo film project by director Jan Lenica employs cut-out animation – a technique that his former collaborator Walerian Borowczyk would also experiment with – for a bewitchingly surreal take on a seemingly simple premise. I have to admit to guessing that Janko is meant to be a farmer, as the only animal that he seems to own is a mechanical cow whose inner workings are on full display. The film’s surreal elements do not stop here, with the shrill flute playing that so angers the locals causing gold to rain down from the heavens that transforms into animal bones when caught by those who fail to appreciate Janko’s questionable talent. Włodzimierz Kotoński’s creepily dissonant score adds to this surrealistic tone, and the series of objects that Janko pulls from inside of the grand piano that he drags to a field to expand his repertoire genuinely made me snort with laughter.

A LITTLE WESTERN [MAŁY WESTERN] (1961)

A cowboy pans a whole bag of gold from a river, only to have it stolen by two greedy and ruthless bandits, but he has no intention of letting these varmints make away with his loot.

This cheerfully playful animation by Witold Giersz is an absolute delight and a stylistic treat, with all of the characters and props painted directly onto the film, or so we’re assured, as just how Giersz was able to do this on a frame-by-frame basis without a whisper of object flicker is anybody’s guess. Indeed, the creative simplicity of the design and the remarkable fluidity of animation ensures that each of the distinctively shaped and individually coloured cowboys – red for the hero, yellow and blue for the bandits – are able to clearly express their intentions and emotions without the need for facial detail. Things take a surrealistic turn when the red cowboy speeds up the process of panning for gold by lifting up the river as if raising a carpet to look for a lost key and scooping up the gold that lies beneath. A short while later, the spirit of Chuck Jones is evoked when one of the bandits whips his finger across his different coloured companion’s body and uses the paint to draw a rope with which to trip up the cowboy, and there’s a wonderfully meta moment when the bandits combine their form and their colours into a large fearsome foe, and the cowboy increases his own size by squeezing out the contents of the animator’s red paint tube. A film that can genuinely be enjoyed by viewers of all ages.

PLAYTHINGS [IGRASZKI] (1962)

Anonymous people fire arrows relentlessly at fleeing animals for food or sport, and then at each other. As the weapons employed by all sides increase in ferocity and deadliness, the mutual destruction gets completely out of hand.

The second short film made by Kazimierz Urbański (his first was the 1960 The Birth of a Sculpture [Gips-Romanca], which is not in this set) places black cut-out figures against plain red or green backgrounds to make a statement about the ultimate consequence of unrestrained escalation of conflict. Familiar the message may well now be, it nonetheless remains every bit as relevant all these decades later, as wannabe despots convince too easily swayed populaces to support military action against countries and peoples because they differ from them in some way. That we’re all essentially the same at heart is subtly illustrated here by having every soldier represented by the same small collection of shapes, chunks of which are cut away with swords or perforated with increasingly deadly rifles and machine guns as the situation deteriorates. It all builds to an apocalyptic peak as the combatants are wiped out by a spring-like whirling spiral that could be seen to represent everything from chemical warfare to all-out nuclear annihilation. The air of building madness is accentuated by Andrzej Markowski’s unsettling experimental score.

LABYRINTH [LABIRYNT] (1962)

The second solo film in this set by director Jan Lenica is a biting political allegory dressed in sublimely tailored surrealistic clothing and is understandably regarded as one of Lenica’s finest. A moustachioed, bowler-hatted man flies free, but when he comes to earth, he finds himself being hunted by the animated skeleton of a large dinosaur. Elsewhere, flying insects with human heads are led into mechanical traps and gobbled up, while another is absorbed by a walrus that then sprouts the insect’s wings and takes flight. With me so far? In a wittily comical sequence with serious undertones, the man sees a woman being abducted by a crocodile/human hybrid, to which he reacts by pulling a vertical spike from a railed fence and firing it at the creature to set the woman free. When he approaches her, however, she ignores his friendly overtures and turns to the felled creature to give it an affectionate kiss. This prompts the creature to return to its feet, pull the spike from its body and throw it through it squarely through the man’s hat, then resume its journey with the woman happily back in his arms.

The design aesthetic and technique should have an instantly recognisable ring to anyone with even a small grounding in East European animation, with backgrounds and characters created from cut-outs of simplified lithographic photos, and sometimes tinted with a single or multiple colours. It’s a style that heavily influenced Terry Gilliam’s animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and the influence on Gilliam extends further to an opening shot of our protagonist flying freely through the air in a manner that was later realised in live action for a sequence in his 1985 Brazil. Like that film, the socio-political undertones of Labyrinth soon become clear, as the man is abducted from the street, probed, tested and catalogued, only to then be completely destroyed by dark airborne creatures when he once again attempts to fly free.

THE CHAIR [FOTEL] (1964)

People file in to a large auditorium in a governmental building, and when those conducting the meeting take their seats on the podium at the front, it is noted that a single seat there remains vacant. Repeated attempts are made to select a new candidate for this role from the audience, but each would-be appointee is prevented from reaching the podium by those around them.

The first of two films in this set directed by Daniel Szczechura, The Chair employs a technique in which characters were pencil-drawn in a variety of poses, then cut out and animated by rapidly switching from between them to create a sense of fluid movement against sometimes densely detailed ink-drawn backgrounds. The result is a fascinating mix of traditional drawn animation and the signature East European cut-out technique. But wait, there’s more, as the entire story is told looking directly down at the characters from an aerial viewpoint using sometimes captivatingly simple techniques to communicate actions (the rectangular block of a leg suddenly extended to trip a would be candidate, for example). As one potential board member desperately attempts to outwit the efforts of the others to block his path to the podium, both the pace and sense of fun increase in tandem, but as ever, there’s some sly commentary on life under authoritarian rule bubbling wittily away just beneath the surface.

THE RED AND THE BLACK [CZERWONE I CZARNE] (1964)

A red bullfighter runs away from, then toys with, then captures and is toyed with in turn, a black bull in a bullring, to which the audience reacts with a everything from admiration to despair in the second film in this set from Witold Giersz. His distinctive visual style is instantly recognisable from A Little Western, but here the single colour figures were painted on cells and animated against a wash-painted bullring background. The result is every bit as delightful as its predecessor and even more inventive, notably when the camera pulls back to reveal the animation table, beyond whose confines the matador and the bull run, landing them on an unlit area that briefly renders the bull invisible to his foe. Giersz then takes this meta element a comical stage further by introducing a three-dimensional mirror into this two-dimensional story, which the bull rotates to reveal the presence of a startled real-world director and cameraman. Artistically joyous (Giersz is able to suggest so much about a character with just a few inventive paint strokes) and enormous fun, it had me laughing out loud when the battle in the bullring is put momentarily on pause so that the matador and the bull can share a beer, and a short while later fall drunkenly into each other’s arms.

EVERYTHING IS A NUMBER [WSZYSTKO JEST LICZBA] (1967)

A sphere falls from the sky from which hatches a man who goes on to explore a monochrome world of mathematics and geometry. That’s all the plot you need to get you started on Stefan Schabenbeck’s intriguing slice of animated numeric gameplaying, albeit one with an ultimately serious point to make about the individual and their place in a controlled society. Schabenbeck lets his imagination run here, as the number 8 is turned sideways to become an infinite loop in which the man becomes trapped, and dividing 10 by 3 produces a result whose infinitely repeating .3 chases him off the screen. The number 2 becomes a saw that cuts a cylinder rolling towards the man in half, and after responding to his stroke of gratitude like an affectionate swan, it transforms into a question mark and then a spiral and floats away. This may all sound peculiar written down, but it makes for oddly arresting and consistently inventive viewing. That every element is drawn in black ink on a plain white background has an appropriately binary feel (am I reading too much into that aspect?), instrumental sound effects are integrated into Zofia Stanczewa’s music score, and the finale unknowingly lays the groundwork for the central concept of the same year’s The Prisoner.

HORSE [KON] (1967)

A horse runs free but is pursued by a man who plans to capture it and ride it like a warrior in the third film in this set from director Witold Giersz. Once again he works with oil paint, but here he creates an animated canvas that sees the medium itself become an element of the film’s aesthetic by having cinematographer Jan Tkaczyk light the canvas in a way that accentuates the three-dimensional nature of the ever-changing brush and palette-knife strokes. Given the difficulties that this way of working must have created, the animation is genuinely extraordinary, capturing the movements of the title creature with fluid elegance and a sharp eye for realistic movement. Kazimierz Serocki’s music score accentuates the energy of the horse and mimics the sound of its hooves as it gallops, as well as cranking up the tension when its persuer is quietly stalking it by a riverbank. The film goes full expressionist when the man mounts the horse and the creature’s alarmed reaction is expressed through a series of blurry whip pans and fast cuts, as the score hits a crescendo of equine panic. Another visually and aurally remarkable work.

CAGES [KLATKI] (1967)

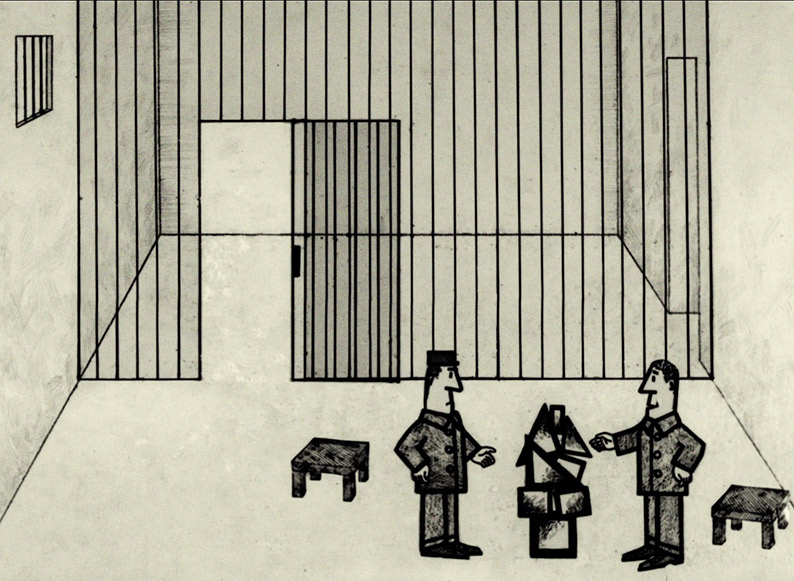

A guard attempts to cheer up a sullen prisoner by presenting him with blocks with which to construct a sculpture, then takes issue with the nature of the work that the prisoner creates and irritably confiscates the blocks. But the prisoner’s rebellion doesn’t end there, and just who is the guardian of who in this world?

Directed by Miroslaw Kijowicz and employing a mood-setting monochrome animated cut-out style, the film’s metaphoric depiction of individual resistance in the face of repressive authority – including one that wears a deceptively friendly face – may be a well-worn one, but was a bold and heartfelt statement at the time, and you won’t have to look far for evidence of why it’s every bit as relevant today. The subtext becomes the text when it comes to the repression of freedom of thought, but the message remains an important one, and the metaphoric final twist acts as a reminder that, no matter how much authority you think you may have been granted, there are always others with more power watching over you and ready to act should you step out of line. Intelligent, sobering, and expertly directed, it also has a sprightly music score by Roman Polanski regular Krzysztof Komeda.

THE STAIRS [SHODY] (1969)

The second film in this set by Everything is a Number director Stefan Schabenbeck is the first to employ Claymation, albeit solely for the opening titles and a transformation effect in the finale. The setup is simple, as a featureless humanoid figure (represented by a hand-crafted posable puppet) makes his way through a landscape consisting entirely of increasingly densely packed and single colour stairways that lead only to more of the same. As the figure trudges up and down this endless forest of stairs, his initial energy soon starts to fade, and eventually he becomes so weary he can barely continue walking.

Initially, The Stairs comes across as a downbeat metaphor for the cycle of life as a long and unproductively weary struggle that ultimately leads only to death. Yet the journey undertaken by this anonymous individual also works as a commentary on the arduous and punishing nature of manual labour, its detrimental impact of the health of the worker, and how we are ultimately just cogs in a large and unfeeling machine, or in this case, steps in the never-ending stairwell of capitalistic grind. A strikingly designed and executed work, captivatingly shot in monochrome scope by cinematographer Henryk Ryszka, with lovely animation of the central character by Marian Kielbaszczak, and a subtly unsettling score from Zofia Stanczewa.

SON [SYN] (1970)

An ageing farmer trudges rhythmically behind his bull to plough the fields for planting while the cows are milked by his wife. When their labour is complete for the day, they gaze longingly at an old photo of them with their infant son, who is now fully grown and works in the city. When he returns home by car that evening, they all sit down for dinner and the gulf that exists between the boy and his parents quickly becomes apparent.

The second of just six animation shorts made by director Ryszard Czekala before moving onto live action features, Son makes creative use of hand-drawn and shaded cut-out figures, which are framed in a sometimes disorientating manner, seemingly abstract shapes that are then revealed to be close-ups of the shoulder or head of the farmer. Given that intelligible dialogue plays no part in almost any of the films in this set, the lack of verbal communication between the son and his parents comes as no surprise, but their implied body language and a small but significant incident involving a dropped piece of bread speaks volumes. There’s no music score here, but the use of sound and silence is telling. Moody, unsettling, and sad.

JOURNEY [PODRÓƵ] (1970)

A man takes a long train journey to visit an isolated house, then takes the reverse journey home.

If that reads like an over-simplification of a more complex plot, I can assure you that it is not – that literally is all that happens in The Chair director Daniel Szczechura’s ultra-minimalist short. There’s no information about where the man is heading or why, just the uneventful repetitiveness of the journey, as he stares out of the train window at the landscape as it scrolls steadily by, while a scraping and ringing rhythm is provided by signal girders on each side of the track as they pass.

It’s a film that we seem to be openly invited to read deeper meaning into, and whether its purpose was to recreate the monotony of long train journeys or was intended as a metaphor for the daily grind of work or something else entirely really will be in the eye of the beholder. Theoretically, it should be as dull as the journey it is portraying, but I found it strangely mesmerising, and the timing of the train’s arrival at the destination station fells absolutely spot on. Maybe this is a stretch, but I couldn’t help wondering if this was an influence on Michel Gondry’s music video for the Chemical Brothers’ Star Guitar.

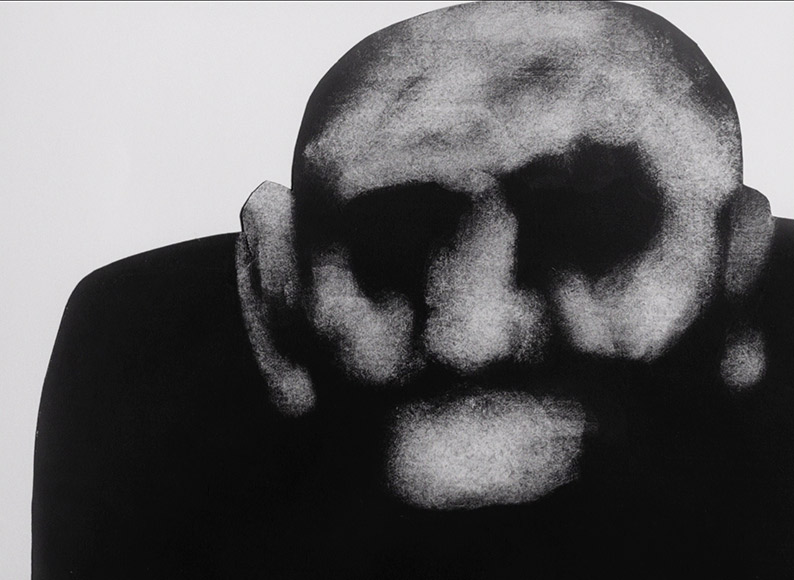

THE ROLL CALL [APEL] (1971)

A second film from director Ryszard Czekala has a similar visual aesthetic to The Son, with hand drawn and shaded monochrome characters animated as cut-outs and the action presented from sometimes unexpected angles. Here, however, the subject is much darker, as the domes of what initially look like military helmets are crammed together while a single set of clipped footsteps can be heard on the soundtrack. Gradually, a touch more light penetrates the overriding gloom to reveal that the domes are shaven heads, and a short while later we catch our first glimpse of the stripped pyjamas that confirm these people are concentration camp prisoners. Further confirmation comes when the owner of the footsteps is identified as a Nazi officer, whose repeated orders for the prisoners to stand up and bend down are a cruel demonstration of authority that has ultimately horrific consequences when one of the prisoners refuses to comply. The first film in the set with intelligible dialogue, albeit only the single word orders “Up” and “Down,” is one of the most soberingly chilling of the lot.

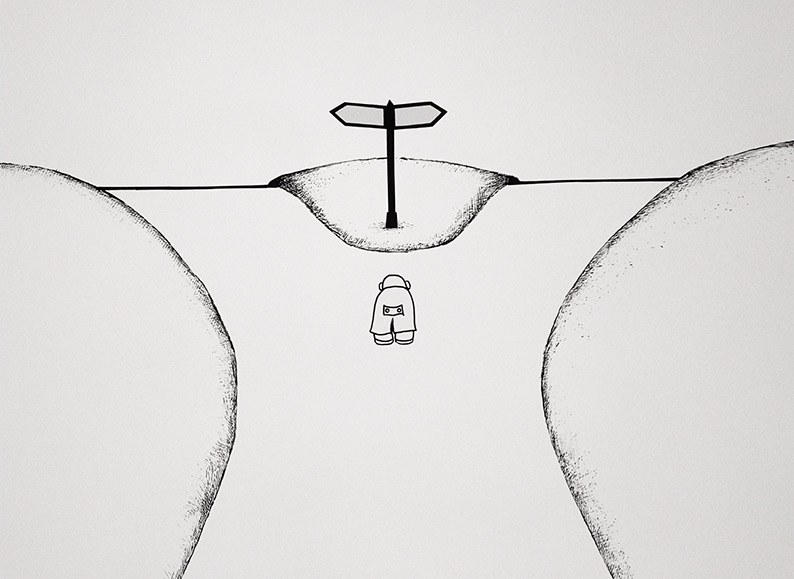

ROAD [DROGA] (1971)

A man walks steadily down a long and unwaveringly straight road until he arrives at a junction, where his indecision about which road to take causes him to initially pause, and then split into two so that the left and the right sides can each take a different road. When they later meet up and attempt to rejoin, however, the two sides have been changed so much by their individual journeys that they are no longer able to match up to reform a whole.

Directed by Miroslaw Kijowicz, Road is an intriguingly simplified exploration of the proposal that every decision we make has potentially huge consequences that can completely change the direction of our lives, a notion that later became the basis for feature films such as Blind Chance [Przypadek] (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1987), Sliding Doors (Peter Howitt, 1998), and Run Lola Run [Lola rennt] (Tom Tykwer, 1998). There’s also a whiff here of Ray Bradbury’s 1952 time travel story A Sound of Thunder, in which the smallest of changes to the past turn out to have serious consequences for the shape of the present.

BANQUET [BANKIET] (1977)

In the large dining hall of a stately home, a group of identical looking waiters hastily lay a long banquet table, and as a string of wealthy guests arrive in cars, the waiters bring in a range of sumptuous food, the sight of which clearly impresses the assembled guests. When they attempt to eat it, however, the situation is violently reversed as the food attacks, dismembers and consumes the guests.

Director Zofia Oraczewska worked with animated cut-out figures to create what is unquestionably the most violent and macabre film in this set, as fingers are bitten off, hands are severed, an eye is pecked out, a chunk is bitten out of a woman’s breast, and empty wine bottles are filled with the victims’ blood. It’s a deliciously grotesque and strikingly designed and animated piece that is wide open for subtextual interpretation, with the social status of the human guests lending it a metaphorically revolutionary air. In that respect, the film pre-empts a t-shirt slogan from the 1980s that also became the title of a blackly comic 1987 British feature from director Peter Richardson, as the process of consumption is turned on its head to allow the food of the over-privileged to literally Eat the Rich.

BARRIER [SZLABAN] (1977)

The first of five films in this collection by graphic artist and painter Jerzy Kucia, who is described by Michael Brooke elsewhere in this set as one of the most conceptually original artists in the medium of animation, and by Ela Bittencourt in the commentary on this film as one of the greatest living Polish animators, if not the greatest. Go in to his second short film, Barriers, with those claims ringing round your head, however, and there’s a good chance you’ll not be ready for what Kucia serves up.

There is no narrative in the traditional sense here, and the film instead seems to be about capturing the essence of a single moment in everyday, as several individuals arrive at a lowered railway crossing barrier and wait there for the coming train to pass. When it does, the focus shifts to two pigeons as they flap about on an initially undisclosed but presumably nearby location, only for one of them to then roll over and apparently die.

What impresses from the off here is Kucia’s technique, introducing his first character from behind and in a manner that initially had me wondering exactly what I was seeing, and two very different animation techniques are employed here. For the arrival of the various individuals at the barrier of the title, Kucia employs a technique known as rotoscoping, and it’s not the last time you’ll see this used in this set. The process involves either filming a subject in motion (or shooting their actions as a series of still images), then printing the frames and the cutting out the characters from each print and placing them in sequence on the animation table to recreate their original movement against a new background. Here, the contrast is pumped up to remove all shades of grey and render the individuals in pure black and white and sometimes in complete silhouette, and the whole scene is given a golden tint to suggest the off-screen setting sun. The pigeons, however, are fully three-dimensional poseable puppets that were made, I’m guessing, with some taxidermal assistance. The barrier of the title, meanwhile, in some ways forms a bridge between these two techniques, being the only three-dimensional model element within an otherwise two-dimensional fra different animation techniques are employed here. For the arrival of the various individuals at the barrier of the me.

The result is an intriguing, quietly haunting work, one that I initially wasn’t sure how to react to, but whose use of stillness, subtle background sound and small moments of repetition really stayed with me and pulled me back for subsequent viewings in search of a subtext I’ve not yet been able to fully decipher. Maybe, just maybe, I’m looking too hard.

A HARDCORE ENGAGED FILM. NON-CAMERA [OSTRY FILM ZAANGAZOWANY NON CAMERA] (1980)

A hell of a title for a cheerfully experimental film by director Julian Józef Antonisz, which employs music and animation to reveal how the actions of one greedy retired woman ultimately led to the collapse of cinemagoing and cultural engagement in general in contemporary Polish society. Yes, you read that right.

While I don’t have the background details to confirm this for certain, I’m fairly sure this was created by painting directly onto clear film acetate, something evidenced by the nature of the image itself. Allow me to clarify. One disadvantage of this technique is that instead of reusing the same facet as you would in cell or cut-out animation, every element has to be redrawn on each frame, but without the ability to overlay the two images to precisely match their shape, their position, and the paint strokes of their shading, what can result is the artwork constantly shifting shape and moving within the frame. Antonisz savvily makes a virtue of this this ever-present motion to add energy and movement to every frame and give the impression that the artwork is being drawn and redrawn almost in real time. The actions themselves play out and then instantly reverse in a ping-pong effect, and while they do illustrate the story being told by the song (sung by Pani Aniela Jaskólska) that Antonisz’s own jaunty score is intermittently put on pause for, there’s a real sense that Antonisz is pulling ideas from his head on the fly and having a whole heap of fun with the process.

REFLECTIONS [REFLEKSY] (1979)

The symbolism feels clearer in the second film in this set from director Jerzy Kucia, which observes the struggles of a newly hatched insect to break free from its pupa while silently being observed by another insect that I initially mistook to be its mother. The infant finally completes its birthing process and begins using its legs to wipe its body clean, only to be suddenly and violently attacked by the other insect. The battle continues as the two plunge into water below, but we soon discover that the conflict is being observed by a far more powerful and destructive creature.

Meticulously drawn and realistically animated in stark, gloomy monochrome, Reflections functions as a downbeat metaphor for both sometimes harsh nature of the cycle of life, as well as a sly critique of life under the oppressive boot of authoritarian governments. Silence and sound effects are once again put to effective use, with music sparsely but tellingly employed in the final scene only.

TANGO (1981)

As I noted above, Zbigniew Rybczynski’s extraordinary Oscar winner was my introduction to Polish animation, and it remains one of the most remarkable short films I have ever seen, in its ambition, in the complexity of its content and timing, and in the sheer work and patience that must have gone into its planning and execution.

The action takes place entirely within a static shot of a small single room, in which sits a bed, a table, a cot, a cupboard (on which lies a tied-up package), a window, and three doors, one on each of the visible walls. As a low-key, almost dour tango plays on the soundtrack, a football pops through the window and lands on the floor. A young boy then appears, looks around to make sure that there is no-one watching, then slips in through the window to retrieve the ball and quietly exit. The ball then immediately pops back in exactly as before and the cycle involving the boy and the ball begins to repeat. The third time that the ball appears, however, a woman carrying a baby enters the room through the door on the back wall, sits at the table and breastfeeds the child, then places it in the cot and exits through the door through which she first entered, none of which disrupts the boy’s actions in any way. As soon as she departs, she re-enters and her cycle also begins to repeat. This time, as she sits to feed the baby, a shifty-looking man in dark clothes and sunglasses climbs in through the same window through which the boy is entering and exiting. He edges along the back wall to the cupboard and steals the package from the top of the cupboard, then makes his departure through his initial point of entry, passing the woman as she enters once again. As the thief climbs out through the window, another man in an overcoat and trilby walks in through the door on the right wall carrying the very parcel that the thief has just taken and places it on top of the cupboard, ready for the thief to re-enter and take it again, which he does as the man takes off his hat and coat and exits through the door on the left hand wall, only to immediately re-enter through the opposite door. None of the characters react to the presence of the others in any way.

Astonishingly, Rybczynski is just getting started here, and as the film progresses, the character count increases until there are something like 30 individuals on screen at the same time, all carrying out their separate and repeatedly looped actions in complete isolation in this small room, seemingly unaware of the pandemonium of movement going on around them. To make this work and to avoid characters colliding or passing through one another would require meticulous planning, but the process is further complicated by the fact that many of these loops differ in length, so Rybczynski had to carefully plan a path for each character that would ensure they would not interact with any of the others at any stage of their circular movements. Given how compressed and how insanely busy the action becomes – multiple people sit down at or otherwise interact with the table at different points, and the bed is used by one woman to sit and tie her shoes, another to change her baby, an old woman to take a rest, and a couple to briefly make love – the planning involved must have been up there with the investigative reasoning of quantum physics theorists. The increasingly layered soundtrack compliments the film’s complex visual density, with the looping tango joined by a building cacophony of sound effects, as a baby cries, plates clatter, feet shuffle across the floor, doors open and close, and a man yells in pain after electrocuting himself whilst trying to change a light bulb. Oh, but there’s more.

To execute this insanely complex multi-looped action in today’s digital environment would be challenging enough, but Rybczynski made this back in 1981 and shot it on film, masking each character off from their background on something like 16,000 hand-crafted rotoscoped cell mattes, and bringing them together on a single reel of film over a seven month period using an optical printer, a device that was more commonly used to matte special effects onto live action for feature films. Because there was no video playback at the time, I remember Rybczynski, in the aforementioned Channel 4 documentary, revealing that they just had to trust that each frame that they shot was accurate to their planning, and that they wouldn’t know for sure until the developed film came back from the lab. Had he made a serious error in the timing or registration, it would have required another seven months of work to redo the film. Small glitches are visible, including a cell outline on the loops of the two women who make use of the bed to dress and change the baby, but these do not detract from the overall impact of the film and act as a reminder that this was the meticulously hand-crafted work by a human artist.

The inspiration for the film sprang from Rybczynski’s curiosity about the people who had previously occupied the room in which he now lived, a notion he chose to explore by portraying an imagined single moment from each of their lives and having them all occur at the same time, which in some ways this makes Tango the first multiverse movie. That he builds to such a complex crescendo of action and sound is astonishing enough, but that he almost invisibly then winds the whole thing down by slyly ending the loops until only a single character is left catches me out every time I watch it. The Oscar win was a first for Polish cinema (there’s an interesting behind-the-scenes story told about this in the extras), and the film’s impact and influence van be spotted in the most unexpected places, including a sequence from episode 45 of season 2 of the children’s animation series Bluey, and director Bill Fishman’s music video for The Ramones’ I Wanna Be Sedated.

SOLO IN A FALLOW FIELD [SOLO NA UGORZE] (1982)

A man shaves, washes his face and dresses, then heads out for a long day ploughing the fields behind his horse, as what may be the ghosts of the past – possibly members of his own lost family – intermittently make an appearance.

Drawn in pen and ink with a keen eye for realism by artist, sculptor and filmmaker Jerzy Kalina, the enigmatically titled Solo in a Fallow Field is a hauntingly executed reflection on the grind of manual labour and its Stalin-era heralding. This is brought home when Bohdan Mazurek’s disconcerting electronic score intermittently gives way to an older nationalist song in which a choir sings of the beloved and cherished Polish land and the labourers who toil it. Intermittently, the action and the sound pause and briefly slip back before continuing forward, in the manner of a hip-hop artist briefly scratching a vinyl record. It’s an analogy that came to me just seconds before a directly related final reveal, one that suggests that the sentiments of the song are not heartfelt but ingrained in the Polish society of the day, and that they are starting to falter.

THE SOURCE [ŹRÓDŁO] (1982]

Ripples in water, in which are reflected various plants, are interrupted by the appearance of a human face that plunges itself towards the camera and into the liquid. Fruit then tumbles from a shelf, onto a table, into a bowl, and even across the strings of a violin. A jar of coloured water then spills in a seemingly controlled slow-motion fall, and as birds cast their shadows over the scene, the liquid seems to rejuvenate previously dying plants before returning to the jar, which slowly rights itself to its original position. By now the volume of the liquid has so increased that it bubbles over and onto the table on which the now upright jar sits. All clear?

The third film in this set from Jerzy Kucia plays like an experiment in ideas and technique, with the two-dimensional black-and-white drawings of the opening giving way to three-dimensional monochrome live action and reverse stop-motion for the revival of the plants and the return of liquid to the jar. I’ll admit that this was film that I was intrigued by without being able to fully grasp the underlying intentions of the filmmaker, despite some assistance from Ela Bittencourt’s commentary track. There’s a whiff of Jan Švankmajer to the composition and reverse-decay of the plants, and Kucia’s stated interest in still-life compositions – which he subtly sets in motion here – are clearly evident in the three-dimensional scenes.

CHIPS [ODPRYSKI] (1984)

Jerzy Kucia is back again for a stylistically arresting look at the repetitive nature of the everyday tasks of ordinary family life using a combination of drawn animation and rotoscoped and processed live action imagery, high contrast monochrome footage that is visible only in part when picked out from the sea of darkness by high-key lighting. A bucket is washed, potatoes are peeled, and the opening of a food can builds to an almost frenzied peak, all of which is intercut with briefly glimpsed imagery of a semi-naked woman and still images of a family by a riverside. Yet as the opening scene reading of a document and the ominous closing shot seem to suggest, these may be memories of a single individual as they are shipped off to a labour or concentration camp. As with previous Kucia films, I may be completely misreading the director’s intentions here, but the film’s suggestive, non-narrative structure does leave it open to audience interpretation.

A GENTLE WOMAN [ŁAGODNA] (1985)

As far as I’m aware, this is the only adaptation of a literary work in this collection, the source being the 1876 short story Krotkaya (A Gentle Creature), by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, which is considerably compressed to fit into in the unhurried 11 minutes of director Piotr Dumala’s film. The plot is stripped down to a its bare essentials here, and the result plays almost as an impressionist – and at one point surrealistically expressionist – reading of the key elements of Dostoyevsky’s more narratively complex tale. While it has the atmospheric gloominess of Jerzy Kucia’s work, it stylistically stands apart, with drawn animation set against pools of a single colour surrounded by darkness, and the image itself textured with horizontal and vertical cross-hatched lines.

It opens with a short narration in which the middle-aged male protagonist mourns the death of his young wife, who is is laid out on a table in their house waiting to be collected for burial or cremation. As the man looks back at their marriage, it becomes clear that however amicably it began, a gulf soon grew between the couple, one that is symbolically represented by the sort of giant spider about which I now have nightmares. It concludes in an action that is taken directly from the source story, but still saddened me enough to send me scurrying back to The Red and the Black to lift my spirits. It’s a downbeat tale, even more so than the story on which it is based, but is most impressively executed.

PARADE [PARADA] (1987)

The final film in this collection is the fifth from Jerzy Kucia, and one that strays as far from the traditional definition of animation as any in this set, being comprised primarily – though not entirely – of rotoscoped live action characters that have been rendered as high-contrast moving monochrome artwork treated with various coloured overlays. The film earns its animation credentials through what Kucia does with this material, transforming the rhythms of manual farm work into a shifting minimalist musical symphony that is egged on by the occasional close-up shots of a violin being played or a drum or cymbal tapped. Depending on your viewpoint, it plays either as a musical elegy to the ordinary working man or a critique of the unrelenting monotony of manual labour, or perhaps both, or maybe neither. Either way, it makes for oddly captivating viewing, and the soundtrack, which moves smoothly between the various rhythms and musical notes, is expertly mixed.

Normally I’d kick this section off by providing details of the restoration and the transfers of the films in this set, but not having access to the booklet that comes with it (not yet, anyway – I have ordered the retail release and should have it soon), in which this information may or may not appear, I can’t say for sure exactly what work has been undertaken. That’s said, many of the films feature closing (or in one case opening) captions that do appear to provide restoration and transfer information in untranslated Polish and which feature a range of company names, which seems to indicate that no one organisation was responsible for the restoration and mastering of all of the films in this set. Indeed, a small number of the films bear no such caption, but the cleanliness and stability of their picture clearly indicates that they have also undergone some degree of restoration.

The first thing to note is that every film here is in excellent condition, being completely stable within the frame and scrupulously clean of dirt and damage. There are a couple of exceptions to that last point, but the dust spots that appear on Banner of Youth were likely present on the found footage from which the film was largely constructed, and while there are visible dots of what look like dust on The Source, I can’t say for sure that these were not part of Jerzy Kucia’s intended aesthetic. Elsewhere, the cleanliness of the transfers is impeccable, something particularly evident on films that make extensive use of black or white backgrounds – the large areas of white on Everything is a Number and The Road are pristine, as are the deep blacks of Reflections and Chips.

Several of the films have a monochrome aesthetic, and this is handsomely captured, with the black of ink and paint always rock solid, and the high contrast look of Jerzy Kucia’s works is reproduced robustly here. Colour washes and overlays are pleasingly rendered, and where brighter colours are employed – notably in the films of Witold Giersz – they are vibrantly reproduced. Overall, a superb set of transfers.

All of the films are framed in their original aspect ratios, which for the vast majority is the Academy ratio of 1.37:1. The exceptions to this are 1.78:1 for The Chair and Journey, 2:1 for The Horse, 2.35:1 for The Stairs, and 1.66:1 for Roll Call.

All of the films feature Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtracks, and all are clear with no trace of damage or wear and boast a very reasonable tonal range, which, unsurprisingly, tends to be slightly more expansive on the newer titles.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default for all of 27 films, but there is almost no dialogue spoken in the whole set.

Audio Commentaries

Several of the films have audio commentaries by experts in their field, and as I stated in the introduction to this review, just this once I’ve elected not to cover them on an individual basis and instead provide a brief and collective overview. My reasons are simple. These are short films, and the commentators are thus restricted in the amount of ground they can cover, and viewers would be far better served by the commentaries themselves than by me listing all of the points that they made. The brief running times also mean that the commentators tend to focus on logically similar areas with each title, albeit in a way that is specific to the film and the animator in question, but for those of us new to both, this material is both welcome and immensely educational. Background details are provided on the making of the films and the individual filmmakers, and while there is some commentary on the works themselves – including discussion of underlying themes – it’s the factual information that I relished hearing and from which I learned a great deal. The best of these are delivered by Eastern European cinema expert Michael Brooke, but all are enlightening and packed with useful detail and interesting observations. If you don’t connect with director Jerzy Kucia’s distinctive style, then the subtextual meaning that Ela Bittencourt finds in almost every aspect of his work may rankle a little, but I like the fact that she is so passionate about films that it took me a while to fully appreciate.

The commentators and films are:

Michael Brooke: Banner of Youth / Love Requited / The Changing of the Guard / The Chair / Cages / The Stairs.

Daniel Bird: Banner of Youth / Love Requited.

Kambole Campbell: Journey / Tango.

Ela Bittencourt: Barrier/ Reflections / The Source / Chips.

Animated Poland (59:29)

Here Michael Brooke kicks off his introductory overview to the films in this set and the subject of Polish animation in general by noting that it’s impossible to comprehensively cover either just one hour. He’s not wrong as it turns out, and if you’re at all intimidated by the idea of listening to Mr. Brooke talk on this for only a whisper short of 60 minutes straight, you really shouldn’t be. Brooke really knows his subject, and the history of Polish animation is so rich with creative personalities and extraordinary films that he is only able to afford a few minutes to each, and the time just rockets by. Starting with Władysław Starewicz, the man widely regarded as the first truly great animator, Brooke takes us on a chronological trip through the enforced formalism of the post-WWII era, into the post-Stalinist golden age of Polish animation, and beyond. The information comes thick and fast and is richly illustrated with film extracts, photographs and quotes, and for those of us who are new to many of the films and filmmakers in this collection, this is an essential and hugely educational watch.

Also included is a Limited Edition Booklet featuring new writing by animation expert Karol Szafraniec, but this was not available for review. As I noted previously, I do have the release disc on order and will update this review accordingly when it arrives.

Oh, what more to say? It’s been almost 20 years since the release of the aforementioned Quay Brothers and Švankmajer collections, and 11 years since the Borowczyk set, and those releases were focused almost entirely on specific filmmakers. For years I’ve ached for a Blu-ray release featuring animated shorts from a range of visionary filmmakers, and for me, this two-disc package from Radiance really is a dream come true. A phenomenal collection of extraordinary films ranging from avant-garde to political satire to creative comedy and utilising a wide range of techniques and artistic styles and sensibilities. Fabulous quality transfers, some excellent commentaries, and Michael Brooke’s terrific hour-long introduction make this a hot contender for my favourite Blu-ray release of the year so far. I cannot recommend this enough. Once again, bravo Radiance.

|