|

I’m not sure if I was alone in being misdirected by the opening sequence of the 1969 horror-thriller, Eye of the Cat. As the film begins, an orange-coloured domestic cat approaches a San Francisco house and unsuccessfully looks for a way in. A disabled woman is then wheeled out of the house and to her car by a man we can presume is her driver, where she lifts herself out of the chair and into the back seat of the vehicle. Unseen by either individual, the aforementioned cat also slips into the car, where it hides behind the oxygen tank from which the woman then takes a couple of urgently needed hits. When the car reaches the beauty parlour that is its destination, the woman finds her feet and walks inside unaided, where she is warmly greeted by the owner and placed in the care of the attentive staff. Again unnoticed by anyone, the cat follows her in and makes its way through the parlour, and as it nears the woman, her breathing starts to falter so seriously that it triggers a medical emergency, panicking the staff. The cat, meanwhile, sits and calmly watches as the pandemonium unfolds.

Despite the complete lack of dialogue, by this point I had convinced myself that I understood what was being implied. This woman has a serious allergy to cats, I reasoned, one that was almost triggered on the drive to the parlour but that really kicked off when the cat that seems to be following her approaches her in the parlour. Is this animal inherently evil or possessed by the soul of some vengeful spirit? Maybe. Has it been trained by a malicious other as the perfect murder weapon? Quite possibly. Either way, I was intrigued. I was also completely wrong. It turns out that the woman in question is named Danny (Eleanor Parker) and the young man who drove her to the parlour is her nephew, Luke (Tim Henry). Danny suffers from emphysema, hence her breathing difficulties, and the dutiful Luke has become her full-time carer. And there’s no way Aunt Danny is allergic to cats. No, the one who has a problem with moggies is an altogether different family member...

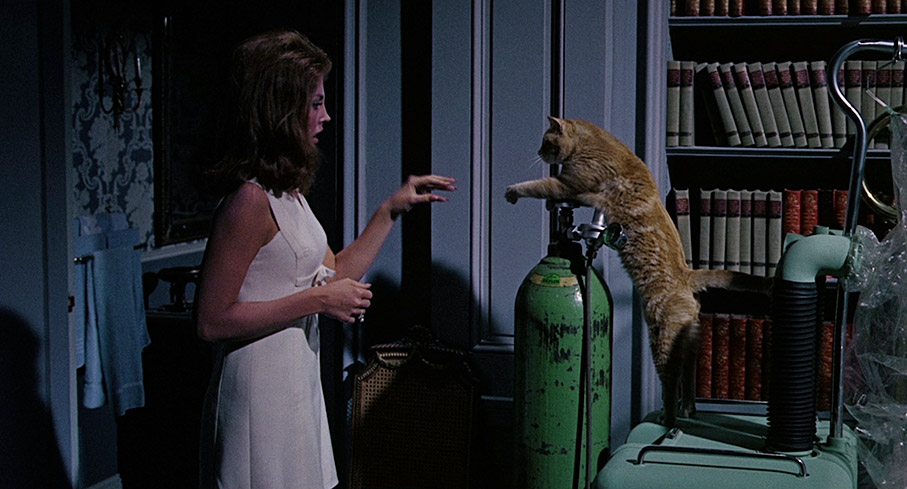

We’re introduced to Luke’s older brother, Wylie (Michael Sarrazin), in a scene that feels deliberately designed to confuse first-time viewers. An attractive woman (Gayle Hunnicutt), one that sharper audience members will recognise from the first scene as a beauty parlour employee, approaches a shoreside motel and wordlessly slips a couple of bills to the manager in exchange for a key, which she uses to let herself into one of the cabins. Her entry startles a naked young woman, one who is unfortunately referred to both in this scene and in the credits as Poor Dear (Jennifer Leak), but seems to amuse the similarly undressed Wylie. The woman has come to take him away, a prospect that seems to intrigue Wylie but that sends Poor Dear into a fury that nearly sees her rip the woman’s hair out by its roots. The still cheerful Wylie agrees to accompany the woman, who then drives him to the salon and orders him to strip, then proceeds to give him the mother of all makeovers. By this point I genuinely had no idea what was going on. It turns out that woman is named Kassia Lancaster and she’s tasked herself with making Wylie look his very best for when he revisits the aunt that he walked out on some time ago but who still regularly pines for his return. Having witnessed the severity of Danny’s recent attack and figured that she’s not long for this world, Kassia wants Wylie to return home and convince the wealthy Danny to make him her sole heir. They could then kill her by interfering with the oxygen tent that she relies on at night, and share the resulting spoils once the will is read.

At this point I did a small double-take. Eye of the Cat was released on Blu-ray by Indicator on the same day Hammer Volume Six: Night Shadows, a box set that includes the similarly titled Shadow of the Cat. The setup of that film also involves a rich woman who is targeted for murder after a close relative persuades her to write a new will in which he will be the sole beneficiary, an inheritance he plans to share with those who assist him in his plan. And all of this unfolds under the watchful eye of a protective domestic cat. Here, however, It’s not just a single vengeful cat but a couple of dozen of them, something Wylie is blissfully unaware of when he agrees to go along with Kassia’s scheme. He certainly wouldn’t have done so if he had. Wylie, you see, is a severe ailurophobe, a man with a panic-inducing and potentially paralysing terror of cats. So sensitive is he to their presence that he can hear the seemingly silent and invisible approach of the same orange cat that hitched a ride with Danny to the salon. When it jumps on him while he is recalling the childhood trauma that first triggered his phobia, he screams and hurls it into an open hairbrush steriliser, explosively electrocuting it in the process.

When Wylie returns to the family home, he briefly reconnects with and scrounges money from his brother, but when he pops in to see his sleeping Aunt Danny, he is mortified by the small army of cats in her bedroom. It’s a deliciously handled pan-shot reveal that is almost ruined by some unnecessary flash-frame inserts of individual cats that were obviously shot in a photographic studio. I also found myself wondering why Wylie, after being able to detect the presence of a single cat even before it reached him, was unable to even get a whiff of the presence of so many just before opening the door to his aunt’s bedroom. Either way, the traumatised Wylie flees and angrily confronts Kassia, who claims to have known nothing about the presence of the cats. When Wylie flatly refuses to return to the house, Kassia seduces him and convinces him to wait for Danny when she makes a weekly visit to a nearby park with Luke instead. She also suggests that Danny could be persuaded to get rid of the cats, but the superstitious Wylie is not so convinced. “It’s not a good idea to take cats lightly, Kassia,” he tells her in all seriousness. At this point, neither are aware that these animals are the sole beneficiary in Danny’s existing will.

This initially bemusing beginning is not the only thing that differentiates the 1969 Eye of the Cat from its genre bedfellows of the day. The first indication that it’s taking a different tack comes during a title sequence in which the screen is repeatedly split and segmented, sometimes playfully in a way that contracts or expands the image, at others to show two simultaneously occurring events, and at one point repeating the same image of Danny during her attack for pop-art emphasis. The second is that none of the lead characters are particularly likeable. Kassia is cold-hearted, manipulative and greedy, Wylie is a directionless and insufferably self-satisfied womaniser who fakes interest in his aunt’s welfare and openly helps himself the cash in her strongbox, and Danny treats the dutiful Luke like crap, even telling him at one point that she hates him and then rubbing salt in the wound by fawning over almost everything the previously absent Wylie does and says. Only Luke, who has taken care of Danny for years and has put up with a ton of shit whilst listening to his aunt go on about a brother who only shows his face when in need of money, seems like a genuinely nice guy, albeit a dull one, but later even he gets to show what a bastard he can be. But adopting the mantle that a character doesn’t have to be likeable to be interesting, the three least initially likeable characters also prove to be the most engaging. Although very 1960s in his ‘anything-goes’ attitude to life, Sarrazin’s cocky charm as the perennially upbeat Wylie is rather fun to watch, which also makes his descent into terror when his ailurophobia is triggered even more effective, in part because it so completely shatters this self-created carefree image. Gayle Hunnicutt, meanwhile, walks a nice line in portraying Kassia as both as an amoral and avaricious ice queen and a seductive temptress – her sexually charged body language and expression when she lies on her bed and teases Wylie over his refusal to return to the house make it easy to see how he could still be persuaded to go along with her scheme.

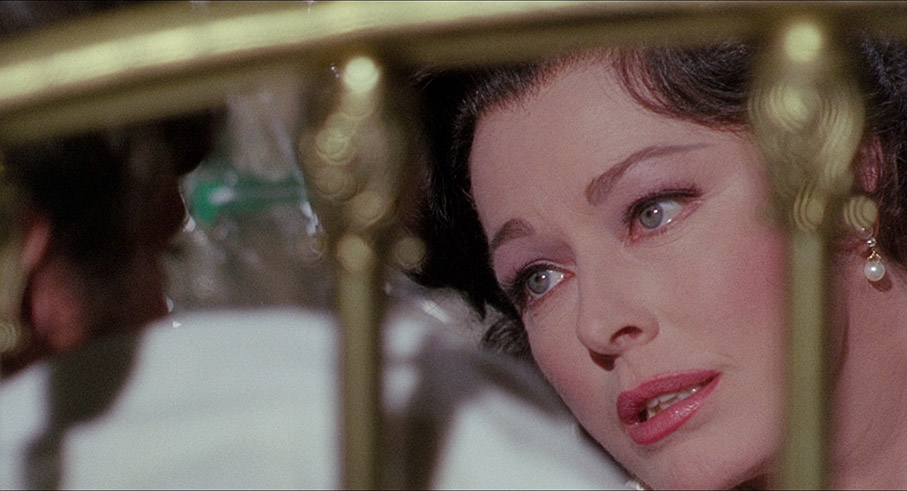

Possibly the most difficult job here falls to Eleanor Parker as Aunt Danny, a woman in failing health who has been targeted for murder to be fleeced of everything she has and who should by default be a figure of instant audience sympathy. Yet the callous ingratitude she shows towards a nephew who has effectively sacrificed his independence to take care of her, coupled with her hopelessly naive fawning over someone whose only interest in her is her money, does tend to cast her in a more pathetic light. Of particular interest are the strong hints dropped regarding the true reasons for her fondness for Wylie. When the two cheerily relax on her bed to chat, she reveals that she secretly watches Luke having sex with his girlfriend and rests her hand a little too high up on Wylie’s inner thigh, and in the awkward silence that follows, a look crosses her face that just reeks of desperate and supressed desire. It’s a superb piece of acting from Parker that hints at so much without a word of dialogue, at least until Wylie cuts her off by suggesting that this inappropriate behaviour for an aunt, which as Kevin Lyons points out on his commentary track is not strictly the case (she was not his uncle’s wife but his mistress, so is not a blood relative). Whether Danny has always fancied Wylie, or suddenly finds herself attracted to him after years alone, or has had a fling with him in the past that she is hoping to revive, is teasingly left for us to decide.

It's this character interplay, coupled with a trio of committed performances and some intriguing stutters in Kassia’s plan of action, that hooked me from an early stage and held my interest even after I’d worked out how this was probably going to ultimately play out. What really surprises is how effectively director David Lowell Rich – who worked primarily in TV and is best known for the enjoyably silly Airport 79 – The Concorde – sells the notion that a collection of twenty or thirty domestic cats could pose a very real threat to life and limb. Wylie’s convincingly handled ailurophobia aside, Lowell Rich plays on what for many will be the real-world experience of the pain and injury that an angry cat can inflict with a sharp swipe of its claws. He also does a bang-up job of presenting the animals as a unified force, as they run together like ripples in a downhill stream, not deviating from their set path and hungrily sinking their teeth into the raw meat on which they are fed. A canny use of slow motion and wide-angle lenses adds to their almost other-worldly air, and a shot in which Danny opens the cellar door to be confronted unexpectedly by the cats, all hissing and yowling and with meat-bloodied mouths, is almost worthy of Hitchcock’s The Birds. That’s not the only sly nod to Hitchcock here. In a smartly staged and genuinely nail-biting sequence, Danny’s motorised wheelchair blows a fuse on one of those famously steep San Francisco hills, and as she fights the potentially deadly pull of gravity, a rescue attempt by an alarmed Wylie is stopped in its tracks by the appearance of what looks suspiciously like the cat he inadvertently fried back at the salon.

Eye of the Cat is a far more enjoyable and effective little horror-tinged thriller than surface impressions might initially suggest. It’s nicely cast, stylishly directed, boasts an occasionally lumpy but intermittently smart script by Psycho screenwriter Joseph Stefano, and has a first-rate score by Lalo Schifrin, one that includes the sort of creepy off-key tones that would soon come to define the work of fellow film composer Michael Small of Klute, The Parallax View and Marathon Man fame. It scores points for keeping me invested in lead characters whose behaviour to each other made me want to sometimes take them aside and slap them and still had me sympathising with Danny as Kassia plots against her and Wylie monetarily exploits her fondness for him, and with Wylie when his ailurophobia later reduces him to a catatonic state. And yes, I did see a late film plot twist coming long before it is revealed (the film does drop an early clue that probably seems more obvious today than it did at the time), but the ending still surprised me enough to have me reaching for the rewind button to check I hadn’t missed something in the immediate lead-up.

The theatrical cut is presented here in 1080p in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio from a Universal HD master, and as we’ve come to expect from Indicator, it looks rather splendid. Detail is crisply rendered, the contrast very nicely balanced – daytime exteriors look terrific here – and the colour is largely naturalistic with a slightly warm hue in the brighter scenes, with mood tones cleanly reproduced when the light levels drop and brighter colours vividly rendered. Only in the montage sequence in which Wyle and Kassia go out for the day and see the sights does the sharpness drop a little and the picture look a tad muddier and the grain become more prominent, suggesting this was restored from an alternative source to the rest of the film, or perhaps shot on different stock.. The image is free of damage and dirt and a very fine film grain is visible.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has also been remastered and is in impressive shape, with the expected minor range restrictions hardly noticeable, especially given how clearly the dialogue, music and sound effects are reproduced – the howling and hissing of cats are particularly effective.

When you select Play, you are offered the choice of the theatrical cut or one that was specially prepared for the film’s TV screening, which for years was the only version doing the rounds. This is presented in standard definition and was sourced from a domestic videotape original, so is obviously going to be considerably inferior to the theatrical print, but its inclusion is still welcome for comparison purposes. Framed 4:3 and mastered from an unrestored print (until relatively recently, this was standard practice), so the detail is fuzzy, the colours are a little washed out, and the contrast lacks anything approaching subtlety, with detail burnt out in the brighter highlights. It’s also peppered with dirt and small instances of print damage, none of which is surprising for a TV print of the day.

The Dolby Digital 1.0 mono soundtrack isn’t bad but is still inferior to the remastered audio on the theatrical cut.

I’ve discussed the differences between the two cuts in a bit more detail in my coverage of the comparison featurette below but will say up front that I far prefer the theatrical cut. Sure, I watched it first, but one of the changes made left me genuinely bemused. All will become clear.

Audio Commentary with Kevin Lyons

Encyclopaedia of Fantasy Film and Television website editor Kevin Lyons provides a detailed and enjoyably appreciative analysis of what he describes up front as an “odd but really rather wonderful little film.” Unsurprisingly, we get a lot of information on the film’s creators, including director David Lowell Rich, screenwriter Joseph Stefano, composer Lalo Schifrin, cinematographers Ellsworth Fredericks and Russell Metty, art directors William D. DeCinces and Alexander Golitzen, title sequence designer Wayne Fitzgerald, and all of the lead actors. He comments on the film’s testing of previous Hays Code restrictions and intriguingly notes that, in a reverse of the expected norm, Michael Sarrazin is implied to be naked more frequently than his female counterpart, Gayle Hunnicutt. He clarifies why the oft-repeated claim that the relationship between Wylie and Danny is incestuous is technically false, and there is some intriguing analysis of particular scenes, including how differently some of them play on a second viewing. He does discuss the substantially reworked TV version, but this is examined in more detail in a separate special feature. A very fine companion to the film.

Kim Newman: Pussies Galore (20:31)

With a title that prompted me to choke on my coffee, the venerable Kim Newman explores what he suggests is remembered as one of screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s lesser credits, and compares it to Hammer’s run of psychological thrillers or the late 1950s and early 60s. He looks at the career of director David Lowell Rich, notes the similarity of some elements to Hammer’s The Shadow of the Cat, and discusses the subgenre of crazy cat films, the San Francisco setting, Lalo Schifrin’s score, and how the 60s youth counterculture was presented on film by middle-aged filmmakers. He also remarks that just about everyone in the film except the family doctor – who is played by favourite British character actor, Laurence Naismith – is in some way scary.

Two Evil Eyes (37:30)

When two different cuts of a film are included on the same disc, this is the very sort of special feature that I love to see included. If I know a film well, I can spot even the slightest change (I’d recognise the insertion of even a single short shot in any cut of Blade Runner by now), but if I’m new to it then it will take several viewings of both cuts to nail all the differences, and there are plenty here. Written and edited by Michael Brooke, this excellent featurette outlines all the ways in which the TV cut differs from the theatrical original by comparing relevant sequences side-by side, as well as providing textual clarification. The changes range from the usual TV censorship of ‘unacceptable’ language (‘damned’, ‘hell’, etc.) to the use of alternative takes and newly shot footage to provide more detail on characters and their relationships, or to overexplain details that were already clearly inferred. What little real violence there is in the original cut has been trimmed here, all drug-taking references have been removed, and any shots in which underwear is clearly visible – which include an impressively physical catfight (no pun intended) between Kassia and Poor Dear – have been edited around. Most peculiar of all is the complete transformation of the later scenes, where a platoon of cats has been reduced to a single orange moggy, shots of which appear to have been specially filmed for this version and which seriously water down the palpable threat that the animals represent. It’s also noted up front that for years this TV cut was the only one freely available, something that has been thankfully corrected by the re-emergence of the theatrical version.

Theatrical Trailer (2:08)

An oddly creepy trailer whose opening sequence borders on the avant-garde and which suggests a work that is far more supernaturally based than it proves to be.

Radio Spot (1:02)

A typically hyperbolic audio trailer that talks of a “house of crawling, creeping evil,” and claims the film will “test your nerves beyond limits no other motion picture has taken you.”

Image Gallery

70 screens of promotional images, posed star portraits, lobby cards, German and American press book pages, whacky exploitation suggestions (theatre managers are encouraged to hand out single packaged after-dinner mints disguised as “anti-tension pills”), advertising sheets, press clippings and international posters.

The accompanying Booklet kicks off with full credits for the film, which is then explored in engaging and revealing detail by head of the IFI Irish Film Archive, Kasandra O’Connell, who apparently has a particular interest in feline-related horror. There’s certainly plenty of it out there. Up next is a reproduction of a news story based on events in the film that was printed in Star-Times, a Universal Pictures promotional pressbook that was designed to look like a tabloid newspaper. After this is a syndicated piece that appeared in American newspapers in the summer of 1968 that attempts to play up the film’s tenuous link to the hippie scene, following which is a second syndicated piece focussed on former model, Gayle Hunnicutt, who talks about her aims for her new acting career and her turbulent relationship with actor David Hemmings. Finally, we have three contemporary reviews, including an unexpectedly positive one from Films and Filming. As ever, the booklet is well presented and illustrated with stills and promotional material for the film.

Another film I got more from than I was expecting, Eye of the Cat is an intriguing blend of caper movie, offbeat family drama and psychological horror, all tinged with a whisper of the supernatural. It’s entertaining, well made, and boasts a handful of impressively handled set-pieces and a spattering of genuinely unnerving moments. Another handsome presentation by Indicator featuring two cuts of the film, a fine commentary track, a solid overview of the film from Kim Newman, an excellent comparison featurette and a typically strong accompanying booklet. For genre fans, most definitely recommended.

|