| |

"The prison depicted in this story, as well as all characters, are fiction. They bear no connection to reality whatsoever." |

| |

The caption that opens all four Female Prisoner Scorpion films |

| |

"Women commit crimes because of men." |

| |

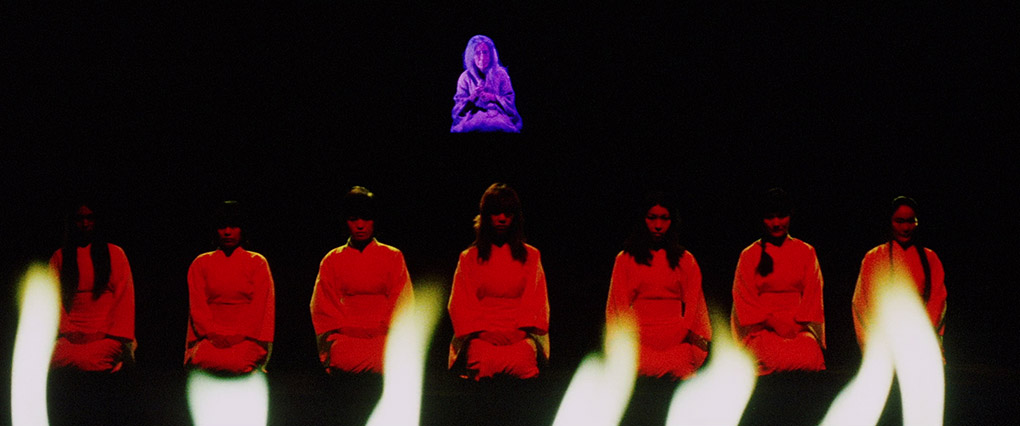

The Old Woman in Jailhouse 41 |

The Women in Prison movie, at least in its more widely known and appreciated form, is in essence a sub-division of exploitation cinema, one consisting primarily of tales of confined women who intermittently put their conflicts with their custodians and each other on hold for long enough to enjoy some lesbian sexual encounters. These films are made by men, probably with a primarily male audience in mind, one partial to the sight of a bit of girl-on-girl action but who as individuals would likely throw a wobbler if their wives or girlfriends admitted to having even having shared a bed with a female friend. Such films have actually been around for decades in a less explicit or even suggestive form than those 70s favourites we all fell in love with. The format has since given birth to a cult TV series in the shape of Prisoner: Cell Block H, and has more recently been leant a touch of populist class by Orange is the New Black, an enjoyable TV drama that also has its share of physical brutality and close-to-the-knuckle lesbian sex scenes, of course.

But if you thought those ex-military guards in series 4 of Orange were an unpleasant bunch, just wait until you get a load of the scumbags that run the women's prison in the Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion. Not only are they heartless, gleefully brutal and prone to cackle with sadistic delight at their every unpleasant action, they do things like forcing the inmates to climb naked over a raised obstacle course that's clearly been constructed solely to allow them to leer at the women's genitals as they clamber obediently above. Mind you, they're not the only salacious chauvinists on display here – just about every man who makes an appearance in the first two films in this set is every bit as bad. In the world of Female Prisoner Scorpion, all men really are bastards. That said, most of Matsu's fellow female inmates are equally toxic, a self-centred and prejudicial bunch who act without thinking anything through and who prove as easy for those with an agenda to manipulate as Daily Mail readers.

The series kicked off in 1972 with Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion and was followed in quick succession by Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41, Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable and Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701's Grudge Song. All starred Kaji Meiko as Nami Matsushima – the eponymous Prisoner #701, aka Scorpion – and the first three were directed by Itô Shunya, who handed over to Stray Cat Rock regular Hasebe Yasuharu for the fourth. Each has the same opening textual disclaimer (see above) and the same theme song, a musical lament for the fate of women titled Urami Bushi sung by leading lady Kaji Meiko but re-recorded by her for each film and later purloined by Quentin Tarantino as part of the magpie's nest of borrowings from which the Kill Bill films were constructed.

It's worth noting that these are not your regular Women in Prison exploitation movies, and frankly only the first film really qualifies for that label in its entirety, although all four films do have their prison sequences. Even with this in mind, they're likely to catch devotees of this particular sub-genre on the hop. If you come for the topless women then you'll find yourself in pig heaven even before the opening titles of first film have played out, but if so then you will likely be bamboozled by the eye-popping experimentation on display elsewhere. And I'm not exaggerating here – imagine, if you can, what would happen if you put a Women in Prison sexploitation film, a rape-revenge drama, Seijun Suzuki's Tokyo Drifter, Kobayashi Masaki's Kwaidanand Paul Schrader's Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters into one of those teleportation pods from The Fly and made a feature film from the biologically melded result and you might just have a flavour of how Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion and Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 play out. And this playful and inventive embracement of artificiality is not confined to specific sequences but seeps into the more obviously exploitation elements, from the sometimes extraordinary framing and shifts of lighting to the cartoonish leering of the male authority figures and violent blows that rarely even look like they're making any contact and which rely instead on exaggerated sound effects to sell them as remotely real.

Like all the best antiheroes, Nami favours stoicism and silence over witty one-liners and explosions of verbal anger, and when tormented responds only with an icy stare that just oozes defiance and vengeful intent. As the series progressed, this was often narrowed down into a single eye curtained by her long black hair (at one point she is actually slapped into this pose), an almost supernatural image that has become more familiar to western audiences in recent years through J-horror works such as Ringu and The Grudge. Nami also sports an iconic costume made up of a long black coat and wide brimmed black hat, one worn only outside of prison and on missions of targeted vengeance. And despite her sometimes icy demeanour and taciturn manner (in the third film she speaks only two lines of dialogue, in the fourth only a single word), she remains the central focus of all four films and a consistent figure of identification and sympathy, a woman who takes appalling punishment so that we may feel a sense of righteous satisfaction when she kicks against the odds and punishes those who have wronged her or those few who get close to her. That she has also found favour with female exploitation movie fans as a feminist icon is hardly surprising, given her role as a righteous avenger in a world run and controlled by reprehensible and abusive men.

And so to the individual films.

| Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion [Joshû 701-gô: Sasori] |

|

As situation and character-setting opening scenes go, the one that kicks of the first film in the series is a bit of a belter. As the Japanese flag flaps in the wind and a uniformed official makes a presentation to warden Goda for his service to the state in front of his militarily lined guards, the ceremony is disrupted by an alarm announcing that two of the inmates have chosen this moment to escape. One of them is Nami, the eponymous prisoner #701, whom we first encounter as she flees through marshland with Yukiko, her comrade/friend/lover (it's left for us to decide which, but they're certainly close), pursued by a posse of angry prison officers and dogs. Despite putting up a spirited fight, both women are quickly caught and hauled back to the prison and a long spell of solitary confinement.

I've yet to see a film or TV series in which solitary confinement looks anything but awful, but here it's grimmer than most, a deep and dark-walled dungeon into which water constantly drips and where you spend your sentence hog-tied on the floor. And when you do get a meal then it's brought to you by a sadistic female trustee who laughs at your misery and pours the food onto the ground beside you with the encouragement to eat like a dog. In the Scorpion films, in keeping with its manga origins, the law of binary oppositions applies, and if you are painted as bad – and almost everybody is – then you're usually portrayed as irredeemably evil and utterly deserving of any punishment that Nami will hopefully dish out at a later date. It's something this smug trustee finds out to her cost when she amuses herself later by dribbling scalding hot miso soup over the seemingly incapacitated Nami, who still finds a way to send her persecutor tumbling to the floor, where she is horribly burned by an entire cauldron of the near-boiling liquid. Mind you, things don't improve for Nami when she's freed from solitary, as further extreme punishment is dished out for just about anything she does or even thinks about doing, and by punishing the other inmates as well, the guards are also able to turn them against someone they should rightly be standing in solidarity with.

All of this is captured with impressive cinematic economy and a range of eye-catching camera angles, energised hand-held shots and inventive edits. Intermittently reality gives way to striking expressionism, as when a fight involving an angered and injured trustee sees her transformed by lighting and makeup into a kabuki demon. Most extraordinary of all is the flashback sequence that reveals what Nami did to get banged up in the first place. Where others might give such as a sequence a coloured tint or play games with the soundtrack, Itô goes for artistic broke, throwing reality out of the window in a visually striking blend of stylised imagery, comic book colouring and theatrical artificiality. This includes rotating sets for scene changes and a glass floor through which to film a sexual assault on Nami and clearly see the leering faces of her attackers, and bathing her in coloured light in an expressionist rendition of her mood an intent. It's a genuinely jaw-dropping sequence, one that should by rights jar horribly with what has gone before but somehow doesn't, the way having been paved by the camera angles and lighting tricks of the scenes that precede it. What makes this adventurous approach all the more remarkable is that this was director Itô's first solo stint in the director's chair, and the film was not a self-funded indie project but a genre piece for a long established studio that was probably not used to young upstarts playing such games with their commercial material. And this sequence is not there just for the fun of staging it or as an inventive money-saving device – it's here that we learn how a more innocent Nami fell for and lost her virginity to a corrupt detective named Sugimi (an event memorably symbolised by a drop of blood on white canvas that spreads to become the Japanese flag) but ends up being gang-raped by drug dealers as part of an arrangement to buy Sugimi favour with the yakuza.

Nami's unsuccessful attempt to stab Sugimi on the steps of the Tokyo police headquarters in retaliation for his betrayal is what lands her in the clink, but Sugimi wants her permanently out of the picture, and to that end forcibly enlists the help of inmate Katagiri to engineer Nami's "accidental" death. Nami's sole ally here is Shindo (played by a splendidly self-confident Ôgi Hiroko), a no-nonsense older inmate who appears to side with Nami more out of a desire to enforce a bit of justice on a world where the term seems to have lost all meaning than anything approaching true friendship. And Nami can not only take the harshest punishment, she knows how to turn things around on her jailers, notably when she is thrown in a cell with a female undercover cop, who not only fails to extract the hoped-for confession, but is so effectively seduced by her cellmate that she ends up pleading with her superiors to be allowed to go back in and give it another try.

It all builds to a riot and a stand-off with the guards in which the inmates start to do Sugimi's job for him by swallowing anything that Katagiri tells them about Nami and making her the target for their anger and violence. That the opportunity arises – by chance, as it happens – for Nami to turn things around on Katagiri does not quite deliver the expected rush of cathartic satisfaction, largely due to the unpleasant nature of the fate that she suffers.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion is a mother of a debut feature, one that works splendidly as a stand-alone film (no plot threads are left dangling) and gets the series off to a stonking start. There's more gratuitous nudity here than in all of the films that followed put together, but in other ways the film sets the tone for them to build on or creatively develop in their own always individualistic ways.

| Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 [Joshû sasori: Dai-41 zakkyo-bô] |

|

The second film in the series begins with Nami back in solitary, hogtied on the floor and being mocked by her captors, particularly head warden Goda, who lost an eye in the first film and delights in assuring Nami that she's going to spend the rest of her life in this dungeon. Well, almost all of it. For his own daffy reasons, just for one day he decides to take her out and parade her in front of a visiting Inspector, one who probably wouldn't have even been aware of her existence had Goda simply left her where she was. Mind you, even Goda could hardly have realised that Nami spent her time in the dungeon transforming a spoon in to a shiv by methodically scraping it against the concrete floor with her mouth, and when dragged before the Inspector and her fellow convicts, the first thing she does is use it to try to take out Goda's other eye.

This incident triggers a short-lived riot, and while the other prisoners are punished with hard labour, Goda decides that the best way smack Nami down is to have her crucified with ropes to a felled tree and have four of the guards rape her in full view of her fellow inmates. This, he figures, will destroy her status as a figurehead for rebellion. In the real world this would likely inspire her comrades to beat the living shit out of every authority figure they could lay their hands on, but so easily swayed are these desperate women that when being transported back to prison, a group of them beat seven bells of shit out of Nami for allowing herself to be abused in this way. Say, what? She was crucified on a dead tree when they attacked her, for fuck's sake! What was she supposed to do, think defensive thoughts? This beating leaves Nami in a state of apparent near death, but when the guards are alerted, she springs to life and strangles one of them with her chains, allowing her and her heartless fellow inmates to break free. This prompts Goda to order a widespread search, ostensibly for all of them but primarily for Nami. No doubt about it, Goda really has it in for Scorpion.

The girls hole up in an abandoned village (one half-buried by what looks like volcanic lava), where Itô softens us towards them a little by revealing a little about them, including the crimes that led to them being banged up in the first place. And despite how poorly she was treated by her comrades, Nami once again comes to their rescue when one of their number nips out to visit her nearby located child, a move that even the cops in this film saw coming.

It's after this that we get our confirmation that it's not just the men who work in prisons who are lecherous toads when a tour bus is stopped by a police road block and the men contained within start slobbering at the prospect of a bunch of escaped female prisoners, then amuse themselves by feeling up the young female tour guide. Astonishingly, this is not some drunken bachelor party but a family outing – there are women and kids in this tour bus as well, but that seems to have no effect on these ghastly representatives of Japanese manhood. When they stop for a break, three of them spot one of the escapees on a cliff top and proceed to gang rape her and then toss her body into the raging waters below. I, for one, was itching to get to the inevitable scene in which the prisoners hijack the bus and give these awful bastards the eye-busting pounding they all deserve. Any sense of satisfaction to be derived from watching them get their just deserts, however, is undermined when the escapees treat the women on the bus almost as badly as their horrible husbands, then at the first opportunity dump Nami in the road to distract the police and allow them to make their escape without her.

All of which is handled with the style and energy of its predecessor, but if you thought the flashback scenes in #701: Scorpion were pushing the artistic envelope, just wait until you see what Itô gets up to here. This time around the stylised artificiality – Itô's self-proclaimed 'fiction beyond fiction' – is not confined to a flashback but repeatedly infects and intermittently takes control of the central narrative. This first peaks when the escapees discover an old clairvoyant in the abandoned village and the house in which she sits collapses around her, and in the sequences in which she and Nami appear to be bolted to the camera as it glides between characters, creating the impression that each is sitting in one spot as the world rotates around them. Most audacious of all is the scene in which the old woman dies, is laid out on the forest floor and swallowed up by and seemingly transformed into leaves that are then blown away by the wind. Designed and lit in a manner that foreshadows the heightened visuals and use of vivid colour in The House of Flying Daggers, it also prefigures the transformation of Blair Brown into sand to be then whittled away by the wind in Ken Russell's 1980 Altered States. Other such moments and sequences intermittently pop up to catch you by surprise, as when the hijacked bus enters a tunnel and reality gives way to stylised theatricality to recall the court appearances that sent the women to prison, or when they discover the body of the raped and murdered comrade and the falling waterfall waters turn blood red.

There's so much to discuss and get excited by in Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 and I've only really scratched the surface here – there's plenty to be read into the final sequence alone, which I'm obviously not about to spoil. It's an extraordinary melding of art and exploitation and quite possibly the finest film in this collection. But then there's also...

| Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable [Joshuu sasori: Kemono-beya] |

|

And here everything changes. Well, sort of. If you approach the third film in the Female Prisoner Scorpion series wondering how director Itô is going to top the art house experimentation of Jailhouse 41, it's worth noting one thing up front – he doesn't. The avant-garde elements are still there, but most are tightly ingrained to the narrative rather than operating as sudden shifts of style in the mode of the first two films. From an early stage, Beast Stable has a more serious tone than its predecessors, but in its own distinctive way is every bit as compelling. Indeed, of all of the films in this set, Beast Stable is the one that least comfortably wears the exploitation cinema label, despite a handful of scenes that warmly embrace that quote at the top and give it a loving kiss.

One of these occurs in the opening scene, as Nami is spotted riding a subway train by two detectives, and in the scuffle and chase that follow, one of them – Kondo – slaps on the handcuffs but gets his arm caught in the closing doors of the train, and Nami hacks it off with a carving knife. Okay, I know Japanese kitchen knives are sharp (I have two myself), but good luck cutting through an adult humerus with one in just three slashes. We're then introduced to young sex worker Yuki in what looks like the act of servicing a client, one she rather discomfortingly refers to as 'Big Brother'. I say discomfortingly because we soon discover that he really is her brother. While this might make him sound like the latest in the series' long line of sleazy male exploiters, it turns out he was left brain damaged by a factory accident and is now able to act only on basic instinct, something Yuki accepts and accommodates out of a somewhat extreme form of sisterly love.

Later that evening, she has just conducted her business in the quiet of a graveyard when she catches sight of Nami in one of the creepiest images in the whole Female Prisoner Scorpion series, as a disconcerting rhythmic noise is revealed to be the sound of Nami, crouching and holding Kondo's bloodied severed arm in her mouth, slowly scraping the handcuffs against a gravestone in an attempt to grind through them. What makes this so spooky is the unbroken stare that she directs at Yuki, an almost supernatural image that recalls a famously chilling climactic image from Shindo Kaneto's 1968 Kuroneko, where witch-mother Yone suddenly appears holding her own severed (feline) arm in her mouth.

For the first time since the early scenes in Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion, Nami makes a friend who genuinely cares for her welfare, something she seems uncertain how to respond to after all she's been through and reacts to largely with silent caution. Yuki does all of the talking here, and the first clear indication that a real bond has indeed formed between the two women comes when Yuki vents her despair about the situation with her brother and wonders if she should just leave him to starve, and Nami responds by paying him a visit with the intention of killing him for her.

As the now one-armed but even more determined Kondo continues his now vengeful search, Nami attempts to blend into the background and even takes a job in a sewing machine sweatshop. All of this falls on its face when she is lusted after by a local yakuza soldier, one whose wife burns him horribly with boiling water in a bungled attempt to punish Nami for what she mistakenly believes is leading him on. Nami is blamed by the wife for the assault, which puts her in the bad books of the yakuza boss and the flamboyantly dressed and decorated Katsu, an old adversary of Nami's from her prison days who is now in a position of criminal power. Once again things soon look to be hopeless for Nami, but when one of the gang's sex workers falls victim to a botched abortion at the hands of a drunken yakuza doctor (not the easiest scene in the film to watch, largely due to the distress of the girl in question) and her body is dumped alongside the cage in which Nami is being held, a new motivation for vengeance against male exploitation and cruelty presents itself.

Faced with telling a character-centric story with more emotional depth than its lively predecessors, director Itô here takes his time with scenes that would have skipped by in the previous films and largely limits and precision targets his cinematic experimentation. That's not to say that the film doesn't have its stylistic or surrealistic flourishes: the dog that carries Kondo's severed arm into a public area in what may or may not be a direct reference to a memorable opening image from Yojimbo; the yakuza night club sequence that is strobe-cut to the lights and music; the revenge killing presented as a series of Argento-like sprays of bright red blood on bleached white set; the extraordinary moment when Nami's face appears as a reflection on the window of a targeted yakuza under close police protection; the dream-like rain of lighted matches that fall into a sewer in which Nami is hiding that Yuki drops from street level in an attempt to locate and make contact with her friend.

For some, Beast Stable is the best film in the series, and I completely understand where they're coming from and in some ways share their view. It's certainly the most character-centric and atmospheric, a gripping, noir-tinged crime drama laced with a sizeable dash of 70s yakuza action and run through with Itô's signature surrealist and expressionist touches. I'd hate to be forced to pick a favourite between this and Jailhouse 41 – how handy, then, that both are in the same box set.

| Female Prisoner Scorpion: 701's Grudge Song [701-gô urami-bushi] |

|

The only film in the set not directed by Itô Shunya is probably the least visually distinctive of the series, playing as a more straightforward Japanese 70s crime flick and lacking the eye-catching stylistics of the previous films or the dramatic gravitas of the third. Yet replacement director Hasebe Yasuharu still delivers the exploitation action-thriller goods and some involving character scenes, and if you can distance yourself a little from what has gone before, there's still a good deal to enjoy and admire here.

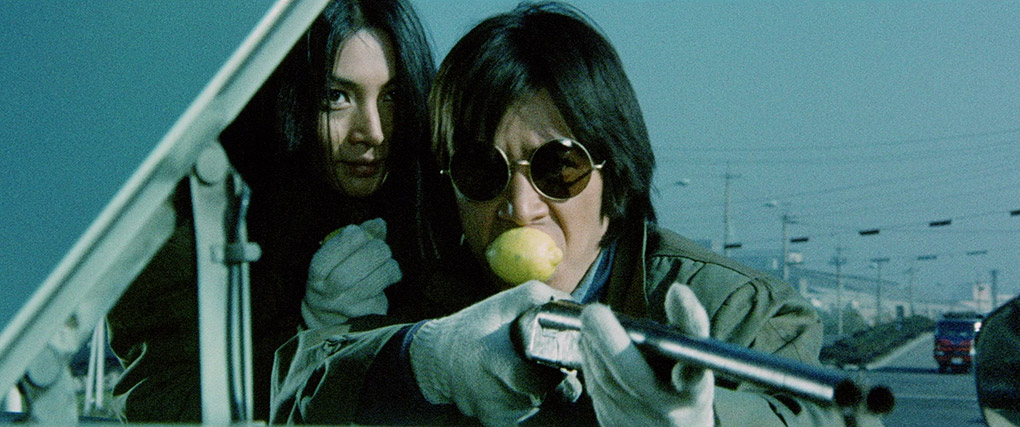

As the film gets under way, Nami is still at large and the police are still actively searching for her, and in a turn of events whose back story I genuinely can't imagine, they find her backstage at a Catholic church wedding. She's eventually arrested but manages to break free whilst being transported to the police station, and despite being badly injured manages to hide in a toilet booth at a nearby strip club (actually, let's call it an 'adult revue'), where she is helped by jaded technician and former anti-war protestor Kudo. It quickly emerges that Kudo also has no love at all for the police, particularly lead detective Hirose, who once supervised a beating that left him permanently scarred and who poured boiling water on his now malformed genitals, all in the name of enforcing 'public safety'. No longer sexually active as a result of this encounter, he befriends Nami more as a partner in crime (when things do develop further it proves significant for both) and allows her to rest up at a junkyard hideout, but the cops soon get wind that he is sheltering Nami somewhere. After taking him in and administering anther serious beating, they tail him to his hideout, but by the time they bust in, Kudo and Nami have made their escape through a trapdoor constructed specifically for this purpose. The two head straight for Hirose's house to ambush the detective, but find only his frightened wife, who in the course of a scuffle falls from a high balcony into the street below, killing her instantly. It takes little more than a heartbeat for the distraught and incensed Hirose to blame Nami for her murder, and he becomes fixated on making her pay dearly for this perceived crime.

Despite the horrors dished out in the earlier films, the brutality on display here really made me wince in places, notably when Nami finds herself back in prison and is awaiting execution for her supposed crimes, time that Hirose spends mentally torturing her and beating her within what in the real world would be an inch of her life. And these are really nasty beatings, with the small-framed Nami held aloft by two burly detectives while Hirose punches her repeatedly and forcefully in the stomach and face until she falls unconscious to the floor. I'm getting a cold shiver just thinking about it. Mind you, these particular representatives of law and order are every bit as wretched as any from the previous films – at one point they force one of the female guards to cooperate with their wrongdoing by gang-raping her in a store room and then threatening to tell everyone about it if she fails to do exactly as ordered. That only one of them gets their comeuppance by the film's end (and not for this, I should note) is the only aspect of #701's Grudge Song that I found really frustrating.

But this is still a solid and enjoyable entry into the series, one that scores a good few wind-ups from the prospect of Nami's looming execution and Hirose's determination to punish her for a crime that she didn't technically commit and that her silence prevents her from even refuting. And just when you're convinced there won't be a trace of the previous film's stylistic artificially, director Hasebe Yasuharu delivers a climactic confrontation that recalls the first film's painterly skies, though even after watching this sequence three times I'm still not sure I swallow how this sequence concluded.

A very solid set of restorations with a very decent level of detail, vivid rendition of the films' sometimes lively colour palettes and only minimal traces of any former damage and dust. The contrast is sometimes on the strong side, which may well be how the films originally played, but no essential detail is lost in the process of nailing those beefy black levels in the first two films and in many scenes the balance feels spot on. In the third and fourth film the contrast is more aggressive, pushing darker portions of the picture into a deep black hole in places. Film grain is visible in the first two films and very prominent in the third and fourth, and intermittently there is a drop in image quality in darker sequences. The very faint flickering evident in all four films also becomes more pronounced in some of the darker and slightly less well preserved scenes. I'm still betting this is as good as any of the films have looked since they were first screened in cinemas. All four are framed 2.35:1, and while this almost always feels right, in Jailhouse 41 there were a number of times when it did feel a little tight, cropping the tops of heads in wider shots in a way that felt a tad uncomfortable, and in a manner not evident in the other three films. Close-ups and mid-shots are generally fine, though.

The linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks are inevitably range restricted and thus a little crisp on the trebles and lacking much in the way of bass, but they are otherwise clear and free of damage.

The optional English subtitles are clear and (appropriately, given the target audience of the discs), slightly westernised in some of the translations, particularly the stronger language.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion

An Appreciation by Gareth Evans (24:34)

Gareth Evans, the always affable director of The Raid and Marantau Warrior, outlines how he came to Japanese cinema in general and offers an impassioned and knowledgeable reading of what makes Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion such a great debut feature, as well as pinpointing the elements that have influenced his own filmmaking. He admits to being made to feel very uncomfortable by the film's treatment of women, but makes a convincing case for a socio-political subtext that plays as a critique of Japan as a nation, one that the interview with director Itô on this disc would seem to confirm. A really enjoyable piece.

Shunya Itô: Birth of an Outlaw (15:47)

Shot in 2003 for a German DVD release, this 4:3 framed interview with director Itô has been re-edited by Arrow to incorporate clips from restored transfers of the films, which make use of the full width of the 16:9 frame. It's a seriously valuable grab, with Itô recalling his early days at the Toei studio as an astonishingly self-confident assistant director (he had no admiration for the studio's output or its resident filmmakers) who was itching to sit in the director's chair. He admits to being influenced not by Japanese cinema of the past, but by German Expressionism and filmmakers such as Buñuel, Bergman and Fellini, and that on landing the job of directing Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion he persuaded writers Kônami Fumio and Matsuda Hirô to throw out their existing screenplay and start again. An essential companion to the set.

Yutaka Kohima: Scorpion Old and New (14:46)

Assistant director on the Scorpion films and later director of the 1977 revival New Female Prisoner Scorpion: Special Cellblock X, Kohima has been filmed in what looks like a private bar with a drink at the ready and has plenty of interesting stories to tell. He talks about the climate of political protest of the time and how this was transformed on screen into Scorpion's anger, how inter-union disputes at the studio once resulted in the police being called to break things up, and how elements of Scorpion's character were actually reflections of actress and singer Kaji Meiko's own. He is largely dismissive of the fourth film in the series and apparently spent his first meeting with director Hasebe Yasuharu assuring him forcefully that he wouldn't work with him unless he had brought some fresh ideas to the table. Another fine extra.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion Trailer (3:03)

A feisty sell for "a controversial and long-awaited movie" that lists the crimes of the characters as it hops through the cast list, asks if a woman's body is poisonous, and boldly assures us that the film will contain "innovative techniques" and "spectacular images."

Jailhouse 41 Trailer (3:11)

A lively but somewhat less effective sell that warns of "the anger of a female convict earnestly bearing her fangs in hell."

Beast Stable Trailer (3:08)

A solid enough pitch that assures us that "The Scorpion thrashes around. The Scorpion exposes the raw souls of all those around her!" Includes a few spoilers.

#701's Grudge Song (3:14)

Scorpion's relationship with Kudo barely gets a mention in this sell for the film's prison-set second half, one that attempts to snag its audience by splashing the word "Rape!" up on screen as an enticement. Erm…

Credits (0:55)

The credits for the film, which are not translated on the film proper due to the importance of providing subtitles for the lyrics of the theme song.

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41

An Appreciation by Kier-la Janisse (28:03)

Writer and film programmer Kier-ji Janisse provides an excellent and infectious appreciation of Jailhouse 41, recalling how she (and others) first discovered the film and making a persuasive case for the Scorpion films in general as strongly feminist works. She explores in fascinating detail how the series fits into both the rape-revenge and women in prison sub-genres, and explores the use of theatrical elements in Jailhouse 41, which remains her favourite of the series. Excellent stuff.

Jasper Sharp on the career of Shunya Ito (10:29)

Writer and film curator Jasper Sharp takes us on a trip through Itô Shunya's films as director, most of which have never been seen in the west. Maybe it's me, but from what Sharp says here, he does not appear to hold Itô in the same high regard as others in the extra features in this set, and wonders just how much of his celebrated stylisation was simply copied from the manga from which the films were drawn. Since no comparative examples are offered up, I guess it will remain the subject of speculation for now.

Takayuki Kuwana: Designing Scorpion (16:35)

The production designer on the first three films outlines how he worked with director Itô, a collaborative approach where anyone could suggest an idea that would contribute to Itô's desire to bring something new to every scene. He explains the thinking behind the costumes and the design of the prison interiors (he rejected realism to create the impression that Matsu was in hell) and usefully explains how aspects of a number of scenes were done, including the blood waterfall and half-buried town in Jailhouse 41, and the match dropping sequence and sewer scenes in Beast Stable. Once again, excellent.

Original Teaser (1:47)

A not too revealing teaser that promises we'll meet "Scorpion and the band of witches" in a film that is "both scandalous and sadistic." Rather wittily, it promises that the film will be "breaking out for the new year."

Original Theatrical Trailer(3:11)

The same trailer as you'll find on the first disc.

Again the credits (0:55) that are not subtitled in the film itself are supplied.

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable

An Appreciation by Kat Ellinger (25:48)

Writer and film critic Kat Ellinger keeps the standard up with a thoughtful and comprehensive appreciation of Beast Stable, kicking off once again (we can assume the interviewees for these extras were fed similar questions) with how she first encountered the Scorpion series, then moving on to an analysis of the film's themes and positive qualities. She talks about the appeal of tough, kick-ass women in cinema, the characters of Yuki and Katsu (whom she regards as "the best pantomime villain" in the series), the links to horror cinema, the film's place within the Pinky Violence sub-genre, Nami as a feminist icon and antihero, her favourite scenes and more. Terrific.

Shinya Ito: Directing Meiko Kaji (17:32)

As with the interview with director Itô on disc 1, this was recorded in 2003 for a German DVD. Here Kaji focuses on the casting and direction of lead player Kaji Meiko and the development of her character over the course of the three Scorpion films that Itô directed. The two didn't get off to the greatest of starts (it seems you can blame Itô's youthful arrogance for that one), but he admits that in the course of their close if sometimes fractious working relationship he discovered many wonderful things about her, and now feels sorry for what he put her through. There's some interesting analysis of the character of Scorpion and of Kaji's performance, brief coverage of the casting of Shraishi Kayoko and Lee Reisen, and an interesting story about how he pressured the Toei company president when it looked like the first film might get shelved.

Unchained Melody: A Visual Essay by Tom Mes (21:30)

A typically and splendidly learned trip through the film and television career of lead player Kaji Meiko by the venerable Tom Mes, illustrated with stills, posters and a clips from the films under discussion. The Stray Cat Rock series, Lady Snowblood and the Scorpion films are singled out for the impact they had on Kaji's development and fame as an actress, but the work she did before and after is also given coverage, as is the secondary career she developed as a singer. A solid introduction to Kaji's work.

Original Teaser (1:46)

Not a bad sell and a violent one, which concludes with the news that it will play on a double-bill with Waru: Teacher Hunter.

Original Theatrical Trailer (3:08)

The same trailer as you'll find on disc 1.

Once again we also have the credits (0:55), which are not subtitled on the film in order to provide a translation of the song lyrics.

Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701's Grudge Song

An Appreciation by Kazuyoshi Kumakiri (11:13)

Shot in what looks and sounds like the corner of a parking lot at night, this interview with filmmaker Kumakiri Kazuyoshi has a wider focus than its predecessors, targeting all four Scorpion films and Kaji Meiko in particular, whom Kumakiri appears to have had quite a thing for – he describes her as beautiful three times in the space of a couple of minutes. It's a bit scattershot but interesting, and Kumakiri concludes by urging us to watch as many Japanese films as we can. Okay then.

Yasuharu Hasebe: Finishing the Series (19:49)

Shot in 2006, again for a German DVD release, this interview with #701's Grudge Song director Hasebe is another useful grab for this set, particularly as Hasebe worked with lead player Kaji Meiko on several earlier projects, including Retaliation and three films in the Stray Cat Rock series. His early days as a clapper-loader for Nikkatsu and his departure when they switched their output to Roman Porn are both covered, as is his approach to picking up where Itô Shunya left off on the Scorpion films and his later work for cinema, V-Cinema and TV. On the modern state of the Japanese film industry he tellingly claims, "The bad times didn't just start recently, they've been like that for ages."

Jasper Sharp on Yasuharu Hasebe (16:54)

A largely fact-based trip though director Hasebe's career, one in which Grudge Song gets only a passing mention, but there's some interesting focus on the director's 'Violent Porno' work for Nikkatsu, one example of which – the unappealing sounding Rape, the 13th Hour – Sharp describes as "the most reprehensible film he ever made."

They Call Her Scorpion: A Visual Essay by Tom Mes (40:00)

After setting the scene with information about how the series got under way, largely using stories you'll also hear in the interviews with director Itô elsewhere in this set, Mes takes us on a richly detailed trip through the Scorpion films and particularly the development of Nami as a character. The underlying themes and several keys scenes from four films here are analysed in film school depth, and while the later revival films do get brief coverage (and a couple of extracts), they are clearly not the central focus of this piece. A fascinating essay, and Mes nicely nails the power of Nami's steely stare when he suggests that it "brings out the true face of anyone it captures."

Trailer (3:14)

The same trailer as on disc 1.

Credits (0:55)

As before.

Also included in the set is a Booklet featuring an extract from Unchained Melody: The Films of Meiko Kaji, an upcoming book on the star by critic and author Tom Mes, an archive interview with Meiko Kaji, and a brand new interview with Toru Shinohara, creator of the original Female Prisoner Scorpion manga, but this was not supplied with the review discs. I'll update this review if we get our hands on a copy.

Like many, I'm guessing, I came to this collection aware of the Female Prisoner Scorpion films but having seen none of them, and was frankly blown away, particularly by Itô Shunya's extraordinary ability to move effortlessly from exploitation to avant-garde and back in a single scene, and the sheer level of thought and imagination that has gone into the shooting of just about every sequence in the first three films. The fourth film may be a little less adventurous in its approach, but it's still an entertaining work and one I'm seriously happy was included in this set. Terrific films, splendid extras and a strong presentation from Arrow. Highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for Japanese names throughout this review, except on the titles of the extra features, which have been reproduced as they appear on the menus in the western style of surname last.

|