|

Following a catastrophic earthquake in 1887 that obliterated ninety per cent of the country and ninety-nine per cent of the population, the island of Goto was cut off from the rest of the world. As all members of the Royal Family were amongst the victims of the disaster, the isle is now ruled by Governor Goto III, who lives in his fortress-residence with his wife Glossia. Unknown to him, his wife is having a passionate affair with handsome young Lieutenant Gono of the Governor's guards, and the pair plan to take a small boat and leave the island. But matters are complicated when petty criminal Grozo, after escaping execution through trial by combat, is appointed to a lowly position on the Governor's staff and begins making his own plans to win Glossia's love.

Of all of the films in Arrow's superb collection of films by Polish filmmaker Walerian Borowczyk, Goto Isle of Love [Goto, l'île d'amour] was always the one that I was most apprehensive about covering. It is, after all, the film that launched this restoration project in the first place and is a firm favourite with those who already know and love the director's work. But then, one person's masterpiece is another's... well, feel free to choose your own descriptive noun. And for the first half-hour of Goto, my initial apprehension just would not shift. Yes, it's intriguing, intelligent and bewitchingly filmed, but whatever it was that had fired the enthusiasm of those who put so much time and effort into getting this film restored seemed to be flying a little over my head. I don't really know what I was expecting, but I'm not sure this was it.

Then about halfway through there's a sequence in which Governor Goto takes his wife to the beach. Here the pair cheerfully play hide and seek like a frisky courting couple, then Glossia suddenly and unexpectedly has her dreams of escape dashed when Goto spies the boat in which she was planning to secretly depart with Gono and pushes it out to sea, blissfully unaware that his actions have torn a hole in his wife's heart (her sorrow is doubtless deepened by the fact that the boat quickly takes on water and starts to sink, making it clear that their escape plan would have failed anyway). But just as she seems ready to run off and leave her soaking wet husband by the shore, she puts her unhappiness aside and rushes to protect him from the cold and retrieve his uniform cap, which has been blown off by the wind, actions that here seem more than just those of a dutiful wife. And the whole sequence is magical. You want me to explain why? I'm not sure I can. There's little in Borowczyk's short films or his first feature Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal to prepare you for the emotional clout that this scene delivers, or indeed Borowczyk's sensitive handling of it, framing Glossia in long-held close-up to focus our attention on her despair, which is heartbreakingly communicated by actress Ligia Branice (that's Mrs. Borowczyk to you). The effect is cranked up a several notches by a spellbinding extract from Handel's Organ Concerto in G minor, Opus 7. It's no coincidence then that the same piece of music underscores the equally affecting climax, whose content I'm not about to reveal here.

What follows – as Grozo puts a plan into action that at first appears to have been triggered by chance but is later revealed to have been meticulously orchestrated – prompted me to reassess all that had gone before, every spoken word and seemingly inconsequential action. Long before the film's end I found myself under Borowczyk's spell and mystified by my earlier uncertainties and eager to watch it again to better appreciate the sort of signals that only hindsight can reveal.

As you might expect from Borowczyk, at least if you made your way through the glorious collection in Arrow's Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation dual-format release, Goto is a precision tooled film. Arrestingly shot as a series the almost two-dimensional compositions in Borowczyk's favoured front-on style and lit in a manner that casts almost no shadows, the rich black-and-white imagery has both a draughtsman's intricacy and an expressionist's feel for backgrounds and locale. And in a move that plays like it has specific meaning but that I like to think is every bit as intuitively random as the mono to colour switches in If...., Borowczyk intermittently breaks the visual continuity by inserting single shots of colour into this very monochrome world. The effect is both jarring (the first time it happened I almost reached for the rewind to confirm what I'd seen) and strangely comforting, brief glimpses of what feels almost like an alternate reality, one in which you can imagine that things will perhaps work out better for the protagonists than they do in the grey world in which they are imprisoned.

There's a sense that time has stood still on the island of Goto since it was isolated by the earthquake, and that walls are allowed to crumble and decay in part because the inhabitants lack the will to repair them. A dictatorship ruled with a smile and a brutally zero tolerance attitude to crime, its customs are as archaic as its do-it-yourself technology. It's a small corner of Soviet industrial collectivism and Spanish post-civil war militarism that is forever Goto, one where military officers are the ruling class, supplies of key foodstuffs are in short supply, and even seemingly trivial crimes carry a potential death sentence. Those convicted are offered the opportunity for reprieve by engaging in combat with each other for the entertainment of the masses (such as they are, there's never a sense that Goto is particularly well populated), with the winner granted his freedom and the loser publically executed by guillotine. Mind you, it tends to be a bit of a one-sided affair, with a bag placed over the head of the man accused of the greater crime and the other given a pole to liberally beat him with.

It's a little ironic that one of the most compelling aspects of the film whose world is the product of creative fantasy is its sense of realism. In his excellent essay in the accompanying booklet, Daniel Bird describes the film as 'social surrealism', and that's as good and concise a description I've read of a film that's nigh-on impossible to put in a box. The surrealistic elements are there but are in no way overt and have a degree of logic within the film's own meticulously constructed reality – even the very Buñuelian image of two dogs being executed by firing squad feels like a ritual born of the island's traditions, particularly given the illustrious status of their former owner. It's the same story with the technology, much of which has remained unchanged or crudely adapted since the pre-earthquake days, while the lack of available materials and the will to change severely restrict the scope of further technological development. Thus while Gomor's funnel-peppered fly-trap (designed and built by Borowczyk himself, as was the brilliant three-image portrait that so bewitches the school children) may seem ingenious but a little unlikely, there's a very real sense that if events had taken a different turn some time in our past and aspects of societal development had been arrested, then like the retro technology of the bureaucratic nightmare of Terry Gilliam's Brazil, we might all have devices like this in our houses.

If I'm being completely honest, I'm still not sure quite how Goto Isle of Love managed to quietly blindside me as effectively as it did. That midway epiphany is only part of the story, as the grounds for its effectiveness were clearly being laid from the opening scene without my full awareness, something a second viewing confirmed and a third will doubtless underline. And there will be a third viewing, probably as soon as I've signed off this review, and a fourth next week when I've got a bit more free time and do not have Borowczyk's Blanche knocking invitingly at my attention door. An almost Shakespearean tragedy of all-consuming passion, unrequited love and dark machinations laced with dashes of Dostoyevsky, Kafka, and Mervyn Peake, yet at the same time quite like none of them, Goto Isle of Love single-handedly makes the case for the importance of film restoration, without which we might lose such unique and remarkable works forever.

As anyone with even a passing interest in either the films of Walerian Borowczyk or the fine work being done over at Arrow Films will be aware, it was the desire to so see Goto Isle of Love restored to its former glory that was the driving force behind the Kickstarter campaign that raised enough money to restore not just this film, but the shorts that make Arrow's Walerian Borowczyk Short Films and Animation such an essential purchase. At the very start of this new transfer, we are provided with complete details of how the restoration was achieved, and I'll try to briefly summarize the essentials. The film has been transferred in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1 with mono 1.0 sound (although it plays on my amp as mono 2.0 – might have to look at my setup more carefully). The restoration itself was undertaken at Deluxe Digital-EMEA in London, supervised by James White and carried out in close collaboration with project manager Daniel Bird and Walerian Borowczyk's long-term colleague Dominique Ségrétin. With the original negative destroyed in a lab fire (noooo!), the source for the restoration was a 35mm finegrain positive, with some shots scanned from an original 35mm duplicate negative.

So the question everyone who put money into the Kickstarter campaign – or indeed anyone in any way excited by this project (that's all of you, right?) – will be asking is how does this long-waited restoration look? Well, a lot of work was required to bring Goto back to a condition that we'd like to think Borowczyk himself would have been happy with, but it was absolutely worth it. The picture quality is consistently and gloriously good, particularly the spot-on grading of the monochrome image, ensuring black levels are crisp, whites are not burned out, and a fine range of mid-tones are visible. This gives the image a richness that this HD transfer really brings to life, one enhanced by the sharpness and crisp level of detail. Textures in particular – the wood of the train carts, the decaying walls, clothing – are deliciously well rendered, and thousands of instances of dirt, scratches and debris have been carefully removed on a frame-by-frame basis. The brief colour shots have also been most attractively restored, the images having a pastel warmth that contrasts strikingly with the grey world that they intermittently puncture. Grain is clearly visible throughout, but is organic to the film. Given the challenge that faced the restoration team, this is a fabulous job.

The Linear PCM mono soundtrack has also been restored and cleaned up, and despite the sort of leaning towards crisper trebles that is common for a film of this vintage, the soundtrack is clear and clean of background hiss and hum and other sundry damage.

Introduction by artist Craigie Horsfield (8:13)

One of a group of artists based at St. Martin's School of Art in the 1960s who was heavily influenced by the film (one of whom even changed his name to John Goto as a result), Horsfield outlines just why the film made such an impression. Well, sort of. This has clearly been edited down from a longer interview (most interviews are), and Horsfield sometimes hops between points without an obvious link and occasionally seems to be struggling to find the right words. But the message still comes through intact, and the case for a link between Borowczyk's work and that of Chris Marker is persuasively made.

The Concentration Universe: Making Goto Isle of Love (21:22)

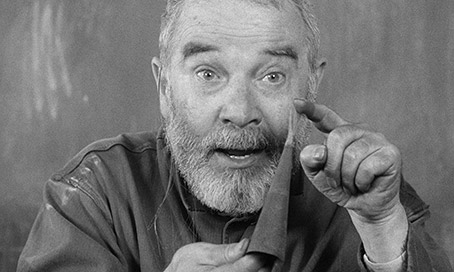

Actor Jean-Pierre Andréani (who plays Gono), camera operator Noël Véry and focus puller Jean-Pierre Platel recall their work on the film, an engaging collection of personal stories, most of them about Borowczyk's working methods. Andréani talks about being cast in the film (the director seemed to assess him by passing sideways glances from a distance), the sense that he was never really being directed, and a moment when the shoot was temporarily put on hold so that Borowczyk could repaint a food hatch that he thought was the wrong colour (and let's not forget this was a black-and-white film). From a technical standpoint, however, it's Véry who proves the most revealing with his description of the director's very specific approach to the film's visual style: neutral lighting, no perspective, no vanishing point, no wide-angle lenses, no distortion effect, sets always filmed frontally and from a certain distance. Travelling shots were permitted to follow movement, but pan shots were unthinkable. "A pan shot?" he exclaims, "How horrible!" He also suggests that Borowczyk directed actors as if they were animated characters.

There is a small sound glitch about 2 minutes before the end of this documentary, where the soundtrack of a clip from the short film Diptych has been inadvertently pushed along the timeline by about 14 seconds. It's not in any way an issue, but this does explain why Andréani is briefly and unexpectedly underscored by the sound of a insects, a dog barking and the honk of a horn.

The Profligate Door: Borowczyk's Sound Sculptures (15:13)

Maurice Corbet, curator of what I'm presuming is a museum of Borowczyk's work, takes us on a tour of sculptures made by Borowczyk later in his career, almost all of which were designed to produce sounds when operated or handled. Intriguing in themselves, they reveal another side to Borowczyk's talent as both an artist and a craftsman, being nicely finished (all wood, no nails or glue) and of solid enough construction to have stood up to a few years of handling without breaking or showing any appreciable signs of wear. My personal favourite was The Black Magic Box, which vibrates sharply when touched.

Theatrical Trailer (3:46)

A smartly edited trailer that employs narration to set the scene and then entices us with seductive extracts, including more than was probably required of the naked bathing prostitutes. If I'm not mistaken (I'll soon be told if I am), it includes a shot that's not in the film itself of Grozo replacing a stolen gun in a cabinet in the schoolroom.

Booklet

Another fabulous Arrow Academy booklet packed with informative essays on the film and its director. Engulfed in Brac-a-Brac is a detailed assessment of the film by Daniel Bird, and includes a fascinating exploration of the reasons for the preponderance of the letter 'G' in the film (as you may have picked up, every name in the film begins with it). A selection of extracts from contemporary reviews (most positive, one dismissive) is followed by Crystal Clear,an appreciation of Borowczyk's talent from acclaimed filmmaker and former critic Patrice Leconte. There's a really comprehensive 1969 article on the director for Sight & Sound by Philip Strick titled The Theatre of Walerian Borowczyk, which is an excellent read and runs for 17 pages. Finally there are detailed notes about the restoration and transfer, credits for the film and a selection of stills.

Once again the dual format box has a reversible sleeve, allowing you to display Borowczyk's original poster artwork on the cover.

I'm fully aware – even more so than usual – that my response to Goto Isle of Love is a personal one drawn as much from the gut as from the head. And despite my attempts to quantify just what it is that makes the film so special, I'm not sure I've even come close to nailing it. It probably matters not. Know only that it is a film you should see and make up your own mind about, and that Arrow's superb Blu-ray is as good a way to watch it as you could hope for outside of a cinema screening of this very same print. Great film, a splendid restoration and transfer and a fine set of extras. Once again, this comes highly recommended.

|