|

Approach the 1970 Hoffman with little to no knowledge of its content, as I did (and if you want to do likewise, skip to the sound and vision details below), and about five minutes in you're likely to catch yourself shifting in your seat in discomfort. It begins intriguingly on a London terminus station platform (actually King's Cross, in case you care), as young Janet Smith (Sinéad Cusack) says a fond goodbye to her fiancé Tom Mitchell (Jeremy Bulloch, who later played Boba Fett in the original Star Wars trilogy), then sends him on his way and watches him depart with an expression of pained indecision and a reluctance to leave. For a second, it looks as though she might change her mind and call him back. Then, after boarding the train and making her way to a seat that Tom found for her, she peeks through the window in the direction of her departed fiancé, grabs her suitcase, and instead of chasing after him as expected, makes her way onto the platform opposite via a train waiting on the adjacent track. A short while later, as night is falling, she arrives at the sort of upmarket London apartment dwelling that I'm willing to bet is worth millions today.* Once inside, she apprehensively makes her way up to the fourth floor and rings one of the doorbells, and the door is opened by the titular Mr. Hoffman, whose initially stone-faced lack of emotion slowly breaks into a creepily unsettling smile. He invites Janet in, but as she nervously enters it's clear she'd rather be anywhere but here, despite a seemingly reassuring, "Don't weaken, Miss Smith," from her host.

Now at this point I still hadn't worked out what was going on, and in my naivety I found myself suspecting that Hoffman was a doctor or psychiatrist whom Janet had arranged a secret appointment with to avoid revealing the details of her condition – whatever it may be – to her unaware fiancé. Something was clearly upsetting her, and her nervousness at entering Hoffman's apartment could just be down to first-appointment nerves. Throwing cold water on this notion is the late hour of her arrival, the fact that she brought a suitcase with her (which she could have been carrying to fool Tom regarding her journey, but…), and clear signs that her initial apprehension has grown into full-blown fear. When Hoffman cuts himself short from directing her to the bedroom (and at this point we don't know if it's the bedroom or a bedroom) and suggests she might like to visit the bathroom first, she has backed into a corner like a wounded animal, and only moves forward after nervously agreeing that the bathroom would be her preferred destination. Once she enters and shuts the door behind her, she breaks down crying, which Hoffman listens to from the hallway whilst gently stroking the door. Then comes the kicker, the line that made me choke on my sandwich, as Hoffman breaks out in the sleaziest of grins and says to Janet through the door, "Please make yourself look as if you want to be fertilized." Excuse me?

Okay, here's the thing. Any critical examination of a film like Hoffman is going to require getting into more detail about exactly what is going on and how those involved respond to it, and if you'd prefer to go into it not knowing this, as I did, then here's your second warning. If you've made it this far and want to know no more, then hop ahead to the final paragraph or click here.

Still with me? Good. It gradually emerges through conversational snippets that Janet is Hoffman's secretary at an unspecified firm, that he knows something about her or her fiancé that could be extremely damaging to them, and that the price of his silence is for her to spend this week with him at his apartment and bow to his every whim. There's a brief glimmer of hope when Janet reminds him that he promised to treat her with respect, which is worryingly dashed a few seconds later when Hoffman responds, "Any man suffering massive sexual frustration would be out of his mind if, getting the girl of his dreams, he didn't put her to... full use." It's thus not surprising that Janet spends as long as humanly possible in the bathroom, whilst Hoffman waits with increasing impatience for her to come to bed. When she does, however, he sets his alarm clock for 6am, takes a couple of sleeping pills, turns over on his side and goes promptly to sleep. What, exactly, is he up to here?

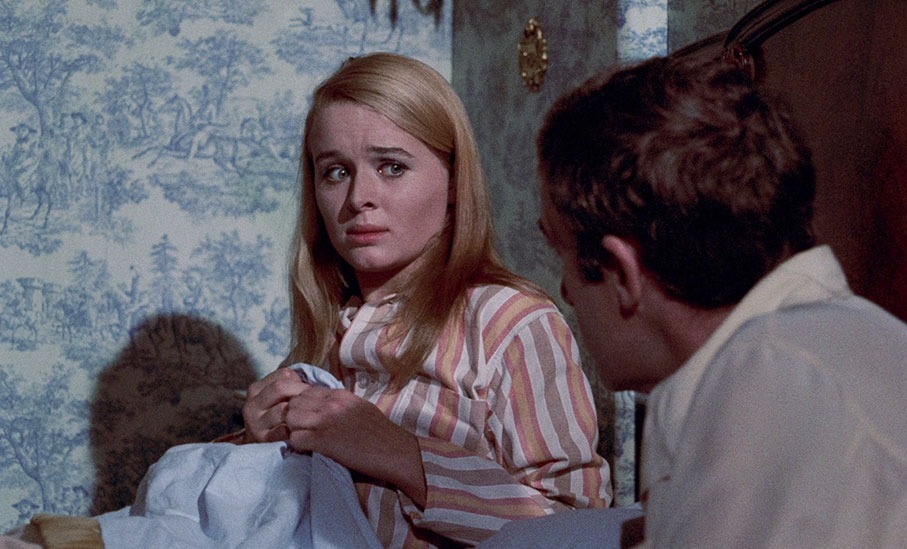

For the first 50 minutes, Janet responds to her predicament as you might expect, with a mixture of fear, distress and supressed annoyance and anger. She also is stubbornly non-compliant at times. When taken out for a meal she flatly refuses to eat the snails that Hoffman has ordered (back in 1970, this was considered an exotic and peculiar dish by the average Briton), and tails along grumpily in inappropriate shoes when the two go for a walk on Wimbledon Common. Hoffman's attitude, meanwhile, is perfectly captured when the two pay a visit to Harrods to buy some food, and Hoffman pauses to watch a still deeply nervous Janet standing in front of a row of hanging carcasses of meat, symbolically framed as flesh to be metaphorically consumed by her observer. If that sounds fanciful, know that it's reflected both in Hoffman's claim to Janet that, "I want to eat you, I want to consume you, I want to lick your knees," and in the alternative title of Ernest Gébler's source novel, Shall I Eat You Now?. Twice Janet even thinks better of the whole arrangement and tries to leave. The first attempt is made shortly after her arrival, when she distracts Hoffman, grabs her things and departs, only to be stopped in her tracks when Hoffman calls after her to remind her of the consequences of not seeing the week through. She makes her second attempt that night while Hoffman is sleeping, but on discovering that the front door is now locked she seeks out and then drops the key, the sound of which is loud enough to stir Hoffman and send Janet scurrying back to bed, still dressed in her hat and overcoat.

It's after the Wimbledon Common walk that we get the first signs of a shift in the attitudes of both Janet and Hoffman, and even of the viewpoint of the film itself. This is also where the biggest problems for an enlightened modern audience are likely to begin. On their walk, Janet's shoes have resulted in a blister on her heel, and unable to reach it herself, she thrusts her foot towards Hoffman and almost commands that he attend to it for her. As he does so, she nostalgically notes that he applies ointment to the plaster in the same way as her granny, then scolds him for not even looking at the wound. Afterwards, she dozes and puts up only the slightest resistance as Hoffman gently guides her to the bedroom to rest, and as he watches her sleep, we get our first real glimpse of the lonely and desperate man that lives beneath his surface misogyny. The effectiveness of this moment is a testament to Peter Sellers' impressively nuanced performance, and I did find myself wondering if this was going to be the point at which the power dynamic between the two would start to reverse, in a way that would see Hoffman being taught a sound lesson in gender politics by the newly confident and authoritative Janet. Ah, about that…

A change certainly takes place here. Until this point, Hoffman's only clearly expressed emotions have been self-confident bluster and sleazily expressed desire. He's also been a fountain of often sharp but deeply misogynistic opinion. He expresses his contempt for intelligent and outspoken women, for instance, with the claim that, "All over the world, simple pleasures of the flesh are being ruined by women screaming to be understood." More disturbing are the thoughts he commits to audio tape whilst waiting in bed for Janet, which almost paint him as a potential serial killer: "Every girl is a flower garden with a compost heap at the bottom. And many a noble man has had to drown his dwarf wife in a zinc bath or strangle an idiot girl on a muddy common in order to draw attention to himself. Reality betrays us all." There were times during this first half when Hoffman's musings made him sound like one of those incel idiots of today, whose poisonous personalities repel the very women they somehow believe they are entitled to sleep with and who end up raging against the whole of womankind as a result, instead of taking a good hard look at themselves. Yet from the moment Hoffman watches Janet sleep, there is a concerted effort on the part of both Sellers and director Alvin Rackoff to humanise him and paint him in more sympathetic colours, while instead of gaining the upper hand in their power game dynamic as hoped, Janet starts softening her attitude towards her blackmailer. This really takes off when she and Hoffman are sitting at the piano playing Chopsticks and hits a peak immediately after when Hoffman allows her to call Tom and he pretends to be the long-distance operator, a sequence in which the two behave like mischievous schoolfriends pulling a comical prank.

I'm sure I don't have to outline the issue here. Maybe, just maybe, if these two spent some time together, Janet would learn a little more about the man she previously only knew as her boss, and Hoffman might learn a few lessons about the wants and needs of a gender he clearly has a poor understanding of and callously describes at one point as, "Fallopian tubes with teeth." And I almost bought into this notion here, thanks in no small part to a pair of excellent performances from Sellers and Cusack, who for most of the film are the only ones on screen and who do a sound job of convincing you that the emotional journey that they go through together is real. But to suggest that the route to such mutual understanding is for a man to blackmail a woman into becoming slave to his desires, in the process traumatising her and potentially causing her long-term emotional harm, makes me shudder in horror. And I've not even mentioned the highly problematic ending, which I see no reason to spoil but about which I could write at least another couple of sizeable paragraphs and which really nails the film as a work of its time.

Hoffman was based on an Emmy award-winning 1967 Armchair Theatre titled Call Me Daddy, which was also directed by Alvin Rakoff and which starred Donald Pleasence as Hoffman and Judy Cornwell as Janet, a version I've not seen but would sorely like to for the cast alone. There's no question that this longer film adaptation is a wittily written and smartly directed work, and I found myself in the odd position of being engaging in and entertained by a film even as I was being made to feel uncomfortable by it. The lead performances are a key attraction here, with Cusack expertly communicating Janet's shifting emotional state (so much so that the few moments in which she vocalises her feelings to herself feel unnecessary) and Sellers giving what may be the most naturalistically low-key performance of his career, despite a couple of misjudged semi-comical asides. Intriguingly, it's also a film that Sellers tried to buy the camera negative of in order to destroy it, believing that his performance as Hoffman was a little too close to the man he really was beneath his more comical public persona. Read into that what you will.

Hoffman has been restored by Powerhouse Films at Final Frame Post in London, with the film's original 35mm camera negative scanned at 4K, and restoration work undertaken at 2K to remove dirt and unstable frames. Just knowing that the film is a low-key British drama made at the tail end of the 1960s does tend to paint a picture of what to expect, and as it begins, such expectations appear to be being met, with a glum-looking opening scene on the station platform and very visible film grain. But given that the title sequence involves process work and was probably the only part of the film that could not have been restored directly from the camera negative, this is not a sequence on which any film restoration should be judged. As expected, once the film proper gets under way there is a noticeable improvement, with a far finer film grain, a more pleasing contrast balance, and an attractive, if deliberately low-key pastel-leaning colour palette. Sharpness and picture detail are consistently good, particularly on the favourite indicators of facial close-ups and clothing, and the image is clean of dust and wear. It's framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1 and looks consistently good, really shining in the bright daytime kitchen scenes.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has also been remastered and is clean of any distracting blights, and despite some inevitable restrictions to the dynamic range, the dialogue is always clear (there were a couple of mumbled lines I struggled a bit with, but I'm putting that down to my malfunctioning left ear), essential in a film that revolves around conversations.

As expected (and appreciated), optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Selected Scenes Commentary with Alvin Rakoff (24:52)

Director Alvin Rackoff only gets to talk for about a quarter of the film's running time on a range of chronologically arranged snippets of varying length, but he still covers a lot of ground and what he says makes for fascinating listening. Subjects discussed include the lead actors, cinematographer Gerry Turpin, Sellers' apprehension about taking the role and later denouncement of the film, screenwriter Ernest Gébler and his rather sneaky attempts to get Rackoff fired, having to clear the set one day when Sellers got the giggles, the original TV play and how it led to Rakoff also doing this feature version, and more. He reveals that Sellers and Cusack had an affair during the making of the film, tells a story of what happened to an expensive gift when the couple had a blazing row, and opines that the script is witty but full of misogyny and that today it would be regarded as politically incorrect, then adding, "and rightly so." His parting comment on the film is one I've heard a few times before: "Like most directors I'm proud of it, and like most directors, if I could redo it again, I would."

Alvin Rakoff: Strange Relationships (21:34)

A new interview conducted with what my calculations suggest is the now 94-year-old director, which was filmed outside, presumably in warmer weather to distance him more safely from camera operator Richard Blanshard during the still-ongoing pandemic. It's great to put a face to the voice and hear what he has to say about the making of the film – the only down side (if you can really call it that) is that a lot of what was covered in his commentary is revisited here, including his conflict with screenwriter Ernest Gébler, Sellers getting the giggles during the filming of one scene, his later attempt to buy the negative to destroy it, and the affair that began between the two lead players. What makes this worth watching, even if you've just listened to the commentary, is the extra detail Rakoff provides on each of these subject areas and a sprinkling of new and equally interesting information, including a more thorough look at how the film came about and a teasing extract of the original TV play, Call Me Daddy.

Eddie Collins: An Underexposed Film (27:56)

The film's focus puller, Eddie Collins, is also filmed outside and kicks off with a clear and comprehensive explanation of his job and the once traditional camera crew career path from clapper-loader to operator, as well as the technical challenges he sometimes faces in his role. He remembers director Alvin Rackoff as a charming man who never had a cross word with anyone, Sinead Cusack as being lovely to work with, and Peter Sellers as someone who was cheerful and chatty one day and thunderously uncommunicative the next. That said, he was seriously impressed when on the final days of filming Sellers brought expensive gifts for everyone working on the film, something that never happened on any other production he worked on. He has plenty of good words for cinematographer Gerry Turpin, repeats the story of Sellers trying to buy the negative to destroy the film, and recalls producer Ben Arbeid's surprise at being billed for all the meat that had been on display in the scene shot at Harrods – the head butcher claimed that having the meat under the film lights made it impossible for him to sell to their fussy clientele, so Arbeid had to cough up and asked the crew to help themselves. "I came back with armfuls of meat," Collins remembers cheerfully. "If only I could afford Harrods' prices, because this lamb was the best lamb I've ever had."

Terry Ackland-Snow: Home Improvements (5:42)

A brief chat with the film's draughtsman, Terry Ackland-Snow (which was filmed indoors, making a serious dent in my above assumption about the use of exterior locations in the previous interviews), who looks back at the pre-production planning required for the construction and the use of removeable walls on the main apartment set, working with art director John Blezard on this film and the TV series Shirley's World, and the importance of knowing in advance what colours your cinematographer hates.

Theatrical Trailer (3:19)

Not the easiest film to market even back in 1970, and while this trailer does give a flavour of the content by teasing us about exactly what Hoffman plans for Janet, I doubt it would have sold me on the film had I watched it first (best not to, by the way). The narrational voice of Patrick Allen converses with a woman I could not so easily identify about the story and about Hoffman himself. Allen concludes that Hoffman is "a man who gets his way," to which his female companion responds, "but not the way you think."

Larry Karaszewski Trailer Commentary (3:46)

Ed Wood and The People vs. Larry Flint screenwriter Larry Karaszewski delivers a nicely level-headed evaluation of a film he challenges us to ever have seen or to even have heard of before. He salutes Sellers' performance, but also notes that he could be a self-destructive actor and outlines why he wanted to destroy the film. He admits it's no masterpiece but also that he's quite fond of what he describes as "a compelling and creepy character study" of a character who is a "MeToo disaster."

There are three Image Galleries, with Gemma Wood thanked on each and whom I presume was instrumental in supplying the content.

Production Stills consists of a whopping 85 monochrome promotional photos, 12 colour ones and 9 behind-the-scenes snaps.

Promotional Material has 69 screens containing the following: international lobby cards; four covers of screenwriter Ernest Gébler's novel under different publications, including its original title of Shall I Eat You Now?; lots of press book pages with enlargements of specific sections; a letter sent to local residents by the production company informing them that location filming will be taking place near their homes; Spanish magazine ads (where it is titled Amor a la inglesa, which I believe translates intriguingly as Love of the English); a collection of sometimes misogynistic 'Hoffmanisms' from the film's dialogue; and a sizeable collection of international posters.

Script Gallery has what appears to be every page of the original screenplay, including a final page of handwritten notes, all of which allows you to compare what played out on screen with what was written. The two are closer than I was expecting.

Booklet

Following the credits, there is an interesting examination of the film by Smersh Pod host and Peter Sellers fan John Rain, which expands on details covered more sketchily elsewhere in the extras, with particular focus on the links between the personalities of Sellers and Hoffman. Up next, we have extract from the EMI pressbook summarising Peter Sellers' career to date, which is followed by a short interview with Sellers about the film, presumably conducted before he saw the finished product and turned against it. A further extract from the EMI pressbook focusses on the then unknown Sinéad Cusack, which is also accompanied by an interview with the actor, in which she talks about her family ties and her career ambitions. Reviews of the original TV version and Ernest Gébler's novelisation follow, along with a brief interview with Gébler for RTÉ Television in which he talks about the themes of subsequent stage version, which returned to the original title of Call Me Daddy. Finally, we have three contemporary reviews of the film, all of which praise the performances but criticise the handling of the narrative.

Hoffman is an odd but interesting and little discussed work, one very much of its time and that features elements that I like to think we've moved on from since, but whose dialogue is sharp and whose central performances are first-class. Another fine disc from Indicator featuring a top-notch restoration and transfer and a solid collection of supporting features. Despite its dated sexual politics, it's absolutely worth seeing, and I have no problem at all recommending this disc.

|