| |

“Otherwise, I didn’t change anything in the Stevenson story, and the trouble with the picture is that, in sticking so close to the original, we wound up with a film that was very respectable and rather boring, whereas the people who made versions not as close to the original story wound up with more exciting films.” |

| |

I, Monster screenwriter and producer Milton Subotsky,

interviewed in Cinefantastique, Summer 1973, Vol. 2 No. 4 |

I think he’s being unfairly harsh on the film there. OK, let’s get one thing clear. The 1971 Amicus production, I, Monster, written and co-produced by studio co-founder Milton Subotsky and directed by 22-year-old newcomer Stephen Weeks, is one of many film adaptations of Robert Louis Stephenson’s 1886 novella, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Subotsky has confirmed that he wanted to make the most faithful film version yet of the story, but his ambition was handicapped a little by the fact that the tale is so famous that its titular names have become part of everyday language and are used to describe anyone who displays two very different sides to their personality. And there’s another problem. As anyone who has read the novella will know, the fact that Jekyll and Hyde are the same person and the morally upright Jekyll is transformed into the murderous Hyde by a serum of his own concoction is only revealed in a late story twist. Nowadays, however, this is far and away the most famous aspect of the story, and it’s thus been suggested that this was the reason that Subotsky opted to use a title that made no reference to the book and change the names of his dual-personality lead character from Jekyll and Hyde to the English author-inspired Marlowe and Blake. Sounds reasonable, I guess, but here’s my problem with that theory. Subotsky’s adaptation is indeed faithful to Stephenson in many ways, from plot specifics to the names of supporting characters, but instead of playing the first part of the story as a mystery and going for a later reveal, the script is up-front about the fact that Jekyll – I’m sorry, Marlowe – is experimenting with a formula that transforms him into the more bestial Blake. In restructuring the story this way, Subotsky is acknowledging that no audience is going to be wondering just who this mysterious Blake really is until late in a film based on a story whose twist they are well aware of, which means he must have known that everyone would realise this was an adaptation of Stevenson’s novella from the off. So why the name and title change? I’m not sure that it matters, I’m just curious. So, apparently, was director Stephen Weeks. The answer, it turns out, is simpler than you might expect and tucked away in the extras on this disc. I’ll get to that in time.

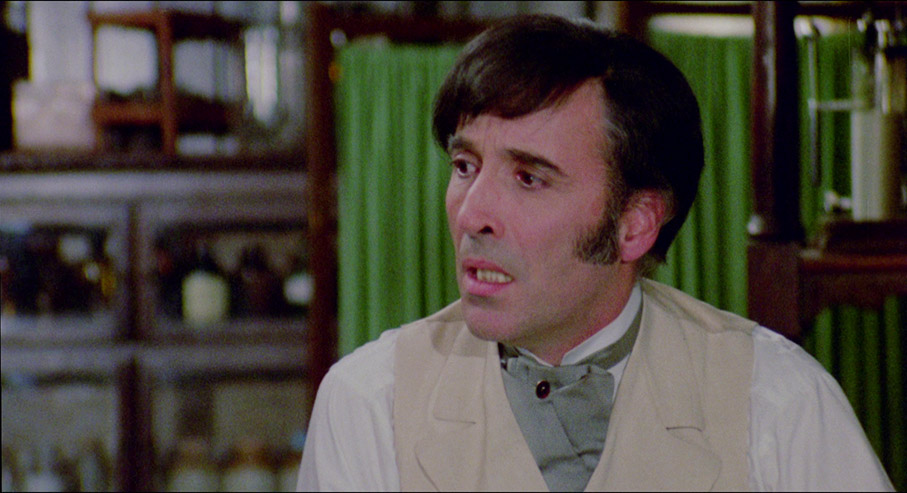

Here we first meet Jekyll stand-in Charles Marlowe (a nicely cast Christopher Lee) when he’s still experimenting with his serum by injecting it into animals, his latest subject being his docile pet cat. It reacts by going nuts and attacking its owner, who instinctively grabs a poker and beats it to death, then reacts with shock and despair at what he has just done. I’ll pause here to acknowledge how well Lee handles this realisation, especially when his thoughts are interrupted by a knock on the door from his butler, Poole (George Merritt), informing him that a Miss Thomas (Susan Jameson) needs to see him and he has to fight to regain a degree of composure. When he meets with Miss Thomas it becomes clear that Marlowe is not a general practitioner in the traditional sense but a psychiatrist, one who appears to be well read in the work of a certain Sigmund Freud, whose theories at this point has yet to find wide acceptance. Indeed, Freud gets quite a workout in the extended cut of the film, which is apparently down to the fact that screenwriter Subotsky’s wife was a psychoanalyst.

Anyway, when Miss Thomas is unable to open up to the good doctor about what’s bugging her, he asks if she’d be willing to give a new and as-yet unproven treatment a go. She’s willing to try anything that might help and he thus injects her with the very same serum he just tried on his cat. I’m sorry, he what? Let’s back up here a second. He injects his cat and it becomes so ferocious that he has to beat it to death and just minutes later he thinks this same serum will somehow be beneficial to a human patient? If this seems a tad irresponsible on his part, as it did to me on my first viewing many years ago, then clarification is on the way, at least in the extended cut. A short while later Marlowe reveals to his friends Utterson (Peter Cushing), Enfield (Mike Raven) and Lanyard (Richard Hurndall) that he has been experimenting on animals for some time and has discovered that the serum prompts a different response in each subject, his theory being that it sets free an aspect of a subjects personality or nature that it has been unconsciously repressing. It certainly has an effect on Miss Thomas, who promptly strips off and attempts to seduce the good doctor, while a loud and bullish male patient named Mr. Dean (Kenneth J. Warren) who agrees to try it regresses to the state of a frightened child. Of course, it’s only a matter of time before Marlowe tries it on himself and the effect is immediate, widening his eyes, forcing is mouth into a rictus grin and transforming him into a man who feels unconstrained by the bonds of morality or the unspoken rules of privileged society. Initially, it’s not what he does that is a cause for alarm but what he seems to contemplate doing (rarely have a feared more for the fate of a mouse), but he is is soon taking the serum regularly and the effect on his appearance and behaviour becomes increasingly pronounced. His friends remain unaware of Marlowe’s nocturnal activities, but when Enfield relates a story to Utterson about a man named Blake who knocked down and trampled on a young girl, they realise that a door through which the individual in question passed leads to Marlowe’s laboratory, and conclude that he must be blackmailing their friend.

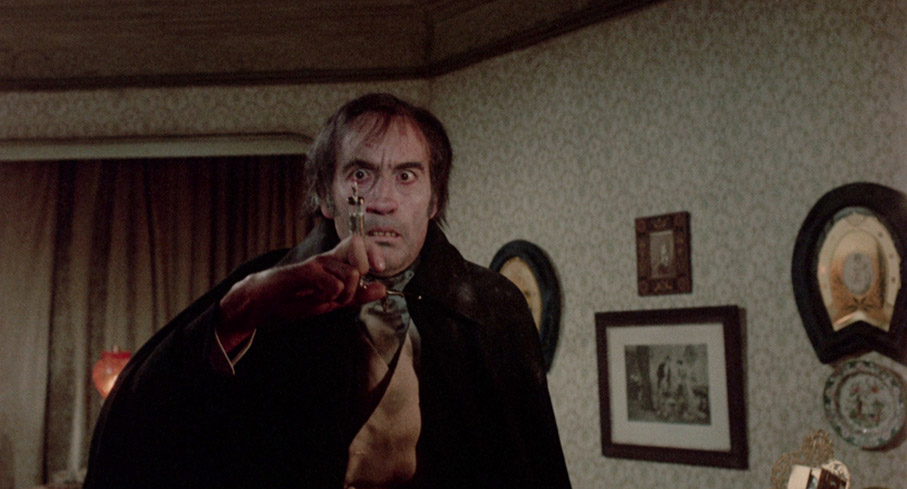

Director Weeks has stated that he intended Marlowe’s serum injections to be a metaphor for the dangers of drug addiction and this certainly registers, with the initially pleasurable and liberating effects of the drug leading to increasingly destructive behaviour and a dependence on an antidote serum that becomes increasingly ineffective. Eventually, Marlowe finds himself transforming into Blake even without the serum, which suggests that it has altered his DNA and that he may now be actually be undergoing a complete and possibly permanent change of identity. That theory is then called into question by the final scene (ending spoiler ahead, so hop to the next paragraph of you don’t know the film or haven’t seen enough variants of the story to guess how it concludes), where the now almost bestial Blake dies and transforms through a series of optical dissolves – one of several signature Hammer elements in this Amicus production – back into Marlowe for the benefit of the watching Utterson. It’s an end-of-film device more commonly associated with werewolf movies, with the serum here standing in for that subgenre’s full moon transformation trigger.

The supporting cast is generally solid, particularly an unsurprisingly subdued Peter Cushing (his wife was terminally ill during the production), the only weak link being ex-DJ Mike Raven’s artificially wooden delivery as Enfield, a man who too often sounds like he is faking an upper-middle-class accent without having given it a few practice runs first. There’s no question that Lee makes for an impressive Marlowe, however, coolly self-confident in company but convincingly vulnerable when alone and things aren’t going to plan and appropriately imposing and later sinister as Blake. He also keeps Blake oddly sympathetic in the early stages, where he comes across almost like a roguish friend whose pranks you enjoy but who later goes too far and just won’t listen to reason. This drift to the dark side is nicely illustrated by two very different assaults on Blake’s part (another spoiler ahead). In the first, he amuses himself by putting a would-be tough guy firmly in his place but elects to leave him relatively unharmed. In the second, he takes an angry dislike to a barroom prostitute who mocks his appearance and beats her to death.

For the most part, I, Monster is an impressively faithful adaptation of Stephenson’s novella, although this does mean that it doesn’t bring anything new to a tale that audiences must even then have been at least partly familiar with, something that was doubtless highlighted by the release of Hammer’s smarter-than-it-sounds gender-swap take of the story, Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde a mere month earlier. Tony Curtis’s (no, no that one) art direction and Stephen Weeks’ fascination with realistic period detail enriches the film’s look, while Carl Davis’s atmospheric and sometimes lively score does likewise for the soundtrack. Throw a stone in any direction and you’ll find an article, review, audio commentary or interview that talks about the abortive 3D process that producer Milton Subotsky had insisted the film be shot in, one that did not need the audience to wear coloured lenses and worked by moving the camera and characters in a certain way within frame, or at least that was the theory. In the extras, Weeks claims it never worked, while Subotsky lays the blame for its failure on Weeks’ lack of understanding of the process. Either way, it’s this that primarily accounts for the use of so many sideways tracking shots and slow drifts around characters and sets, an imposed technique that was a stylistic choice two years later on the part of another up-and-coming filmmaker named Martin Scorsese in his direction of Mean Streets.

The resulting film is a solid and entertaining take on Stephenson’s story that although plays less thrillingly than I remember from my teenage years is still an enjoyable watch. Lee is good in the lead, Weeks’ direction is often stylish (some of it imposed, some very much down to his camera placement), and despite the criticisms frequently aimed at Subotsky’s screenplay, I can’t help thinking he was onto something worthy of expansion here – if ever there was a story through which to explore the misuse of drugs in therapy and Jungian theory about the duality of man, then surely this is it. There’s one small thing that continues to niggle me. Given that Christopher Lee remains instantly recognisable as Blake in all but the final stages of his transformation, I couldn’t help wondering how it is that Enfield – who was part of a group that directly challenged Blake after he knocked down the child – and Marlowe’s loyal butler Poole seem blind to the similarity between Blake and the man they have known for many years. Then again, I’ve never understood how nobody who works with mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent is able to see that he’d be a dead ringer for Superman if he just took off his glasses.

Two versions of the film have been included on this disc, the Original Theatrical Cut and an Extended Edition. For the purpose of this review I went with the Extended Edition as the most complete version, then carried out a side-by-side comparison to see what was removed for the theatrical release.

Only two edits appear to have been made to create the Theatrical Cut, both resulting in the removal of entire sequences. The first occurs 4 minutes 40 seconds into the film and removes 2 minutes and 46 seconds of material. In the excised footage, Marlowe arrives home from the gentlemen’s club at which he relaxes with his friends to find Poole asleep by the door and to whom he hands his clothing when he wakes, then enters his laboratory and starts mixing his elixir. We then return to the club to earwig on Enfield, Utterson and Lanyon as they discuss Marlowe’s theories about letting loose the repressed aspects of our personalities.

The second cut occurs 18 minutes and 17 seconds in and lasts for two minutes and 43 seconds. In this excision, we see a post-experimentation Miss Thomas expressing shame at her serum-triggered behaviour, a response that Marlowe then analyses and explains using Freudian theory. Later at the club, Marlowe reveals to his friends that he’s been testing the drug on animals, then ponders on its effects and their implications, and the scene ends when Enfield asks him if he’s tested the drug on a human subject.

It seems clear that the decision to remove these scenes was an attempt to tighten up the pace a bit by chopping out most of the Freudian discussion and analysis, but in doing so it removes two sequences that for me do the film harm. The first is the one involving Miss Thomas, which not only shows for the first time that the process can be reversed but that the subject would have a clear memory of what they went through under the drug’s influence and have a moral and emotional response to it. The second is Marlowe’s admission to his friends that he has developed the drug and been testing it on animals, as well as providing specifics of how differently each subject reacts and confirming that the process can be reversed with a second potion. Without this scene, my above comments on how reckless Marlowe appears to be for testing the drug on Miss Thomas so soon after the same potion turned his cat feral absolutely would stand.

Scanned at 4K and restored at 2K by Final Frame Post, London from an original CRI element supplied by StudioCanal, with StudioCanal’s legacy HD remaster the source for the two short sections in reels one and two which make up the film’s extended cut, the 1080p 1.85:1 transfer here is generally solid, but does vary a little in the crispness of its detail. There is a slight softness and an intermittent lack of vibrance to several of the wide shots, though whether this is down to the condition of the source material or the production itself is hard to say, as in all other respects the image is consistent throughout. The colour has that sometimes slightly unnatural look that was common with film stocks of the period (or at least how they have aged) and an earthy hue to some interior scenes that appears to be a grading choice, as some night exteriors have a more blue-grey tone to them, and this does collectively contribute to the film’s convincingly unglamourised period feel. A fine film grain is visible and the image is very clean.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is clear and free of errant noise or damage, with particularly pleasing presentation of Carl Davis’s score.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are included.

Audio Commentary with Stephen Weeks

A newly recorded commentary by director Weeks, and how much you get out of it may depend on whether you listen to this before or after the one with Weeks and Sam Umland detailed below. I went for that one first one because its recording predates this and I reasoned that this newer one might build on what was said there. As it happens there’s quite a bit of overlap between the two, though each has its unique aspects so it’s useful to have both, but listen to one after the other and you’re likely to be saying “heard that” a few times. Weeks confirms here that he enjoyed creating the elaborate sets, that he still doesn’t know why the names of the lead character(s) were changed and confirms that the subtext of the film was designed to be reflective of the drug-taking that was all around him at the time when the film was made, but that he didn’t personally partake in, no sir. He reveals that almost all of the effects were done in-camera, that once famed animal impersonator Percy Edwards created all of the film’s animal noises, and although an admirer of Christopher Lee’s acting abilities, he seems oddly keen to paint him as vain and over-sensitive. He’s dismissive of the 3D process in which the film was supposed to be shot and tells an amusing story of how it was approved, even though no-one but Subotsky could apparently see the effect, though there’s an interesting alternative take on this in the Subotsky archive interview below. A worthwhile listen, though I have to admit to slightly preferring the more spontaneous commentary with Sam Umland, as this one has something of a rehearsed and read-out quality.

Audio Commentary with Stephen Weeks and Sam Umland

This earlier commentary was recorded on 30 October 2005, something we are handily informed of by host Sam Umland even before the opening titles roll. As I noted above, there is some overlap here, with the same story of how the 3D process was approved and Weeks’ claims about Christopher Lee’s vanity given another outing, though the second of these is tempered with some sincere praise for Lee’s acting. We do learn here that the film’s production budget was £110,000, that Subotsky’s partner Max Rosenberg was someone that Weeks never saw but was known to be good at securing production funding, and Weeks confirms that Cushing was under a tremendous strain due to his wife’s illness. There’s a brief but interesting discussion on the title, some coverage of the film’s Freudian aspects, and in a moment that did make me smile, Weeks confesses that when revisiting the film he was expecting Mike Raven to be worse than he is.

The BEHP Interview with Peter Tanner – Part One (69:45)

In what on the face of it seems like an odd decision but was undoubtably thought through, here we have Part One of a British Entertainment History Project interview with editor Peter Tanner whose second half appeared on the earlier Indicator Blu-ray of The Beast Must Die. Back when I reviewed that disc I noted that I was looking forward to hearing this, so entertaining was Tanner in that second part, and it absolutely lives up to my hopes. Tanner had a rich a varied career spanning many decades, and even late in his life when this interview was conducted he was a most entertaining raconteur with a very clear memory, and the 70 minutes here are littered with interesting anecdotes and information about the pre-Second World War studios and those who worked within them. The audio quality on this is every bit as good as the content.

Carl Davis: I, Maestro (18:08)

A new and enjoyable interview with composer Carl Davis, who talks about his approach to scoring the film, as well as his belief that any available source novel for a project should be the score composer’s bible. His recently revived friendship with director Weeks is covered in some detail, talk of which includes details of Weeks’ passion for restoring old buildings and how he turns scripts he cannot sell into novels.

Introduction by Stephen Laws (5:57)

Horror novelist and Peter Cushing fan Stephen Laws provides a typically concise introduction to the film, commenting on the correct pronunciation of ‘Jekyll’, the 3D process, the production design, Christopher Lee’s performance and the strain under which Peter Cushing was working.

Archival Interview with Stephen Weeks (15:47)

An extract from an interview with director Stephen Weeks, conducted by Stephen Laws in Manchester 1998 at the 9th Festival of Fantastic Films as a prelude to the screening of Weeks’ 1974 supernatural horror feature, Ghost Story. Weeks outlines how he got into the film industry and made his first films, then moves on to I, Monster and what by this point in the extras is familiar territory, expressing his bemusement at why the names of Jekyll and Hyde were changed and why the 3D process proposed by Subotsky was doomed from the start. See the following special feature for an alternative take on this.

Archival Interview with Milton Subotsky (181:50)

Edited down from a series of interviews conducted by genre writer Philip Nutman with producer Milton Subotsky during the summer and autumn of 1985 as part of his research for a definitive book about Amicus that unfortunately never made it to print, this extra runs for a whopping three hours, but it as absolute treasure trove for Amicus fans. Nutman steers Subotsky through many of Amicus’s most memorable features and a few others besides, and allows him to talk as long as he wishes on each of them. About some he has only a few words to say, while on others – the 1970 Scream and Scream Again is a prime example – he provides enough information for a hefty chapter of a sizeable volume. Unwaveringly confident in his own abilities and coming across as a combination of a master huckster and all-controlling circus ringmaster, he has often strong opinions about the people he’s worked with and is not remotely shy about sharing them. A few are surprising – he thought Hammer’s breakthrough film The Curse of Frankenstein was dreadful and emphatically states he would never willingly give any director final cut of a movie – and many are revealing, from his having to cut some of Bernard Lee’s scenes in Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors due to the actor arriving on set drunk, to the problems that plagued The Land That Time Forgot, things he was apparently brought in to fix after initially being shut out of the picture. He praises the talents and personalities of some writers and directors but is curtly dismissive of others, and clearly had a real dislike for producer John Dark, whom he at one point describes as “a weasel.” He lets out a small groan at the mention of the 1972 What Became of Jack and Jill? before describing as the worst film that Amicus ever made, but there’s a more fondly positive “Ahh…” when Nutman brings up the same year’s glorious horror anthology Tales From the Crypt. Of particular interest here, of course, are his comments on I, Monster, where he reveals that the 3D process he was trying for was based on something called the Pulfrich effect (I looked it up, it’s for real), and goes on to present his side of the story about why his plan to use it in the film ultimately fell flat, the blame for which he lays absolutely at director Stephen Weeks’ door. The reason he changed the names of Jekyll and Hyde in a story that was intended to be faithful to a novella in whose title they both names feature is also revealed here and it’s painfully simple – the funding just wasn’t there for another Jekyll and Hyde movie in the early 1970s, and changing the names and title effectively fooled investors who were aware of the story but had never actually read it. A tad ironically, he now believes the picture doesn’t work, in part because the book that his screenplay was so faithful to is actually rather boring. In all, this is a hugely entertaining listen, though I was left with the impression that in Milton Subotsky’s eyes, the only one who really understood how to make movies and almost never made a serious error of judgement was Milton Subotsky. Although an audio extra, the discussion is visually accompanied by appropriate posters and stills. There is also a sudden cut-off in the sound about 38 minutes before the end, which a caption explains is due to now lost tapes.

UK Theatrical Trailer (3:01)

An overlong trailer that makes no secret of the fact that this is a retelling of the Jekyll and Hyde story, and warns us with typical hyperbole to “Prepare yourself for the new, the ultimate experiment in evil!” Steady on there. I know the results was unfortunate and the experiment perhaps misguided, but was there really any evil intent here?

US Theatrical Trailer (1:47)

“Recommended only if your veins can stand the cold torment of evil,” warns the sober-voiced narrator in this snappier and less repetitive trailer, though I’m not sure my veins will be as concerned as my nerves on that score.

Kim Newman and David Flint Trailer Commentary (1:47)

Newman and Flint provide a quick overview of the film, giving a mention to the failed 3D process and noting that it has the look and feel of a Hammer production. Newman suggests that Lee’s makeup as Blake has a bit of a Carry on Screaming vibe about it, and hilariously refers to Mike Raven as “the tosser of terror.”

There are two Image Galleries. Promotional Material contains a whopping 129 screens of crisply rendered promotional stills, posters and press book pages. Behind the Scenes features 54 screens of behind-the-scenes photos, including a couple of makeup tests and a few that almost look like promotional stills.

Booklet

Following the credits there is an enjoyable and learned essay on the film by BFI curator Josephine Botting, who champions the detail in Milton Subotsky’s original screenplay (which is now held by the BFI) and points out that the Pulfrich effect that was the basis for Subotsky’s 3D process was later used in a series of broadcasts in 1993 as part of the BBC’s Children in Need campaign. Next there are extracts from a 1973 interview with Milton Subotsky in Cinefantastique magazine in which he rejects the idea that Amicus productions plagiarised earlier film and literary works and reflects on the wisdom of being faithful to Robert Louis Stevenson and the abortive attempt to shoot the film in 3D. This is followed by extracts from an interview with director Stephen Weeks by Troy Howarth in which Weeks looks back at the making of the film and dismisses the 3D process as “nonsense” (as Botting noted in her piece, it was later used by others), also retelling a story of how it got approved that you’ll find more than once elsewhere in the extras. His comments about Subotsky’s appearance and personality, meanwhile, have the unfortunate ring of a man holding a serious personal grudge. Finally, we have extracts from two contemporary reviews and information on the transfer. As ever, the booklet is nicely illustrated with publicity and behind-the-scenes imagery.

A solid retelling of a famous tale that is faithful to its source and would thus make a perfect introduction to the story for anyone who has somehow never heard the names Jekyll and Hyde, though those who know the novella will doubtless take pleasure from spotting the story elements and dialogue that have been accurately reproduced from it. I certainly did. It’s one of Amicus’s most Hammer-like films, and if you’re a fan of either studio or 70s horror in general then you absolutely should see this film and may well have already pre-ordered this disc. And as a Blu-ray release it really shines, with two cuts of the film backed by an absolute slew of excellent special features that I’ve had to miss a few London Film Festival screenings to make my way through. If this is your sort of movie, then this disc comes highly recommended.

|