|

This is the fourth and final box set from the BFI covering Ingmar Bergman’s films, eight films, which in this case include two versions of the same film. As with the other box sets, it breaks down Bergman’s long and prolific career roughly by decade. However there’s a sense that even that isn’t enough to contain Bergman, as some significant films aren’t included, usually because they’re owned by different rightsholders. Even so, despite the gaps, it’s hard to avoid the sense that Bergman’s final decade as a film director for the cinema was an uneven one, in some cases due to circumstances, but it still contains some of his best work. In Fanny and Alexander, Bergman made of the greatest closures to a great career ever committed to celluloid. Except it wasn’t his final film...not quite.

Volume 3 ended with Persona in 1966 and then jumped forward to 1969 and The Rite, made for television but released in cinemas overseas. The first film in Volume 4 came out in 1972. As you might expect, Bergman more than filled that gap with other films which aren’t in this set. The first was Stimulantia (1967). Portmanteau films were in fashion in the 1960s, with many European auteurs contributing to them. The results are frequently uneven, with major short work sitting next to nothing much, and it’s also fair to say that many of the portmanteaux have vanished into obscurity and are now hard to see. That’s the case with Stimulantia, the work of eight directors, put together by Vilgot Sjöman: never released in the UK, it is however available online with English subtitles at a certain file-sharing website. Stimulantia is a mixed bag, juxtaposing fiction and documentary, colour and black and white, 35mm and 16mm. Two segments are adaptations of classic stories: no less than Ingrid Bergman stars in a version of Guy de Maupassant’s story The Necklace, directed by Bergman’s mentor Gustav Molander. Ingmar Bergman’s contribution is Daniel. Bookended by black and white scenes of Bergman sitting by a projector, speaking to camera, the film is mostly made up of colour 16mm home-movie footage of his son Daniel, from when he was a seven-month pregnancy bump on Bergman’s then wife Käbi Laretei’s body to the age of two.

After that, Bergman returned to fiction and made four feature films (including The Rite) in the space of two years. The three cinema films were made for United Artists (still in Swedish, though) and the rights to them are still held by that catalogue – later moved to MGM and now presumably with Amazon. All three films were shot on the island of Fårö, where Bergman had made his home, with his regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist on board, and many of his usual actors present too – Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in all three, and with Gunnar Björnstrand, Bibi Andersson, Erland Josephson and Ingrid Thulin also appearing. (Björnstrand and Thulin were also both in The Rite.) They make a loose thematic trilogy, identified as one of violence intruding on people’s ordinary lives.

Much could be said about the role of horror in Bergman’s work, and Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen), released on 19 February 1968, is a prime example. Artist Johan Borg (von Sydow) lives on an island with his pregnant wife Alma (Ullmann). He is troubled by frightening visions, some not dissimilar to vampires and werewolves, and also of his former lover Veronica (Thulin). Bergman continues the metafictional devices (or alienation effects) of Persona by having genuine studio chatter on the soundtrack during the opening credits.

Shame (Skammen, sometimes called The Shame in English – see Mia Hansen-Løve’s film Bergman Island for more on this), released on 29 September the same year, is a rather more straightforward and less interior work, and the closest Bergman ever got to a war film. Jan and Eva (Von Sydow and Ullmann) are a couple, both originally violinists, who have retreated to their farm home due to the outbreak of civil war. Then the area is bombed, and the couple are captured, and the remainder of the film details their struggle to survive. Nykvist’s cinematography is first-rate as you would expect. All of Bergman’s feature films had been in Academy Ratio (1.37:1) up to this point, even though the ratio had become commercially obsolete in Western commercial cinema a decade and a half earlier. No doubt Bergman was able to do this due his films mostly playing in arthouses which could still show Academy – and given how tightly they are composed these films should certainly not be shown any wider. With the exceptions of Now About These Women and Daniel, all his films had been in black and white, which had also become commercially obsolete, in the late 1960s. The Rite (first shown on 25 March 1969) was also black and white, but that reflected the fact that Swedish television only broadcast in monochrome at the time, and wouldn’t upgrade to colour until the following year. However, even international auteurs had to get with the programme and A Passion (En passion, also known as The Passion of Anna), released on 19 November 1969, became Bergman’s second feature in colour and his first in a widescreen ratio, in this case 1.66:1. Bergman and Nykvist would continue both of these until the end of the former’s career, with the exception of the mostly-black-and-white From the Life of the Marionettes (see below).

A Passion is one of Bergman’s more difficult films, and not just because those metafictional devices (having the four principal actors talking to camera about their characters at points during the film) make another appearance. A lonely divorcee, Andreas (von Sydow) is visited by Anna (Ullmann) and their lives are entangled with those of Eva (Andersson) and Elis (Josephson), who are dealing with turmoil of their own. I’ve mentioned Bergman’s censorship history before in these reviews, and A Passion is notable as the only Bergman feature still to be cut by the BBFC. The film has a subplot involving animal abuse and killing by someone unknown, and at one point Andreas finds a dog hanging by its neck from its lead. This actually looks faked to me, with a model dog, but the BBFC cut it for DVD release on the grounds of animal cruelty.

In the mid-1960s, Bergman had been approached by Martin Bregman of the American Broadcast Company to make a film for him. The result, released on 6 June 1971 was The Touch, which became Bergman’s first film (mostly) in English, with Elliott Gould playing opposite many of Bergman’s regular cast and crew. David (Gould) is an architect who meets Karin (Bibi Andersson) who has been married to Andreas (von Sydow) for fifteen years and has two children by him. David and Karin embark on an affair. Bergman cast Gould after seeing him in Getting Straight (1970). The film was not a success in either the UK or USA, originally released with its mix of English and Swedish dialogue all dubbed into English. It’s not one of Bergman’s greatest films, and Gould does feel a little out of place in the Bergman Cinematic Universe. The BFI have released a fine Blu-ray of The Touch.

After The Touch, Bergman regrouped, and the result was one of his greatest films.

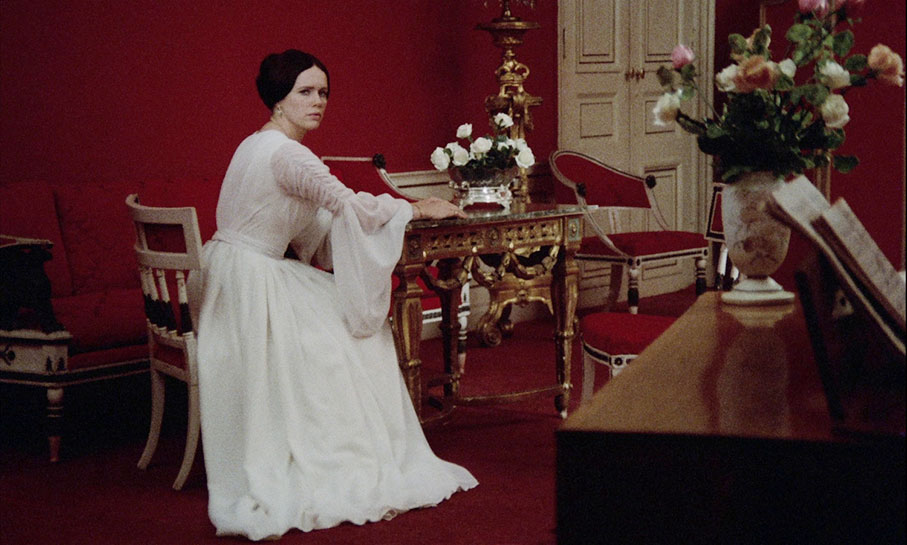

In the large family house in the late nineteenth century, Agnes (Harriet Andersson) is dying of cancer. She is tended by her maid, Anna (Kari Sylwan), and is visited during her final days by her sisters Karin (Ingrid Thulin) and Maria (Liv Ullmann). The film intersperses the present time with memories (or maybe dreams) of all three sisters.

First of all, Cries and Whispers may be a difficult watch because it’s one of Bergman’s most harrowing films – even more so when you consider that at the time it is set, there was little in the way of palliative care. As well as Agnes’s terminal cancer, her sisters’ history contain such things as adultery and self-harm. The film contains a scene that almost made me turn my head away from the screen, the first time I saw the film. (If you’ve seen the film before, you will know exactly which scene I mean.)

Bergman wrote the script while living alone on Fårö. The story came from an initial image of four women in white dresses in a room whose walls and carpet were red. Bergman and Sven Nykvist had been masters of black and white but, given the commercial necessity of working in colour, they made much of that red. Many of the interior scenes only have red, black and white as their colours, other than the actors’ flesh tones. Many films fade to black at the end of scenes, and sometimes to white. Cries and Whispers fades to red.

As The Touch had been a commercial failure, the film with its – on the face of it – deeply uncommercial themes, Bergman had to finance it largely by himself, with the help of loans and some funding from the Swedish Film Institute, also with the four lead actresses and Nykvist deferring their fees. He handpicked the cast, including the return to his films by Harriet Andersson after a number of years. Bizarrely, Mia Farrow was talked about for the role of Anna, but Kari Sylwan was cast. Liv Ullmann also plays Maria’s mother, and her daughter by Bergman, Linn Ullmann, doubles as the daughters of both Maria and Anna, and Linn’s half-sister Lena Bergman, plays Maria as a child. The film was not shot in a studio but entirely on location, at the then-dilapidated Taxinge-Naxby Castle.

The film received rave reviews on its release. Roger Corman, distributing the film via his New World Pictures, even showed it to some drive-in cinemas, with results unknown. It became just the fourth foreign-language film (and first of Bergman’s) to receive an Oscar nomination for Best Picture, with nominations to Bergman for his direction and screenplay, Marik Vos’s costume design, and a win for Nykvist for Best Cinematography. Cries and Whispers remains one of Bergman’s major works. Bergman himself said that with Persona and this film he had gone as far as he could go. “And that in these two instances when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover,” he wrote in his book Images. There is a sense in his remaining films of the 1970s that he was looking for a new direction.

Bergman had worked on television from its earliest days. During the year of 1957, when he made three films for the cinema and directed two stage productions and four radio plays, he had made a production for television, which had launched in Sweden the year before. Mr Sleeman is Coming (Herr Sleeman kommer), a 43-minute version of a one-act play by Hjalmar Bergman (no relation). It was presumably broadcast live and would likely be closer to Bergman’s stage productions than his cinematic work. Other television productions of plays continued, but Scenes from a Marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap) was an original screenplay, and its running time, 282 minutes over six episodes, was nearly three times the length of his longest work to date. Its first episode broadcast on 11 April 1973, it was undoubtedly an event. A cinema version was also prepared, at 168 minutes nearly two hours shorter than the original but still an hour longer than any previous Bergman feature film.

Taking place over ten years, the miniseries and film starts with Marianne (Liv Ullmann) and Johan (Erland Josephson) being interviewed for television and asked the secret of their seemingly perfect marriage. Much of the film (at least in the shorter version – I’ve not seen the episodic version) consists of two-handers between Marianne and Johan, sometimes with one or two other character, as their marriage disintegrates. Other than a brief shot of their being cleared out of the way at the very start so that the interview can begin filming, we never see the couple’s two daughters.

Given that Bergman had been divorced four times by this point, he had plenty of material to draw upon. (His fifth and final marriage, to Ingrid von Rosen, lasted from 1971 to her death from cancer in 1995.) The production was on a smaller scale than some of his films, with Nykvist shooting in 16mm (blown up to 35mm for cinema release), with Bergman’s direction emphasising close-ups even more than usual, and his two leads are lacerating.

Scenes from a Marriage was shown round the world on both large and small screens. The first BBC2 broadcast, in 1975, was a dubbed version, with the voices of Annie Ross and John Carson. This English version was not well received, so the BBC2’s next showing, in 1977, reverted to the original Swedish, with English subtitles. The cinema version won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film. Liv Ullmann was nominated for a BAFTA and a Golden Globe for Best Actress, but was bypassed for Oscar attention for the film being ineligible as a television production broadcast a year before the theatrical release, despite a letter signed by twenty-four filmmakers asking for thw film to be made eligible. Scenes from a Marriage has been produced on stage, and Bergman made his own sequel in 2003 with his final film, Saraband. In 2013, Hagai Levi remade the serial as a HBO miniseries, starring Oscar Isaac and Jessica Chastain.

Bergman remained on television for his next project, a film of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, which was notable as the first television production with a stereo soundtrack. It was first broadcast on 1 January 1975 and also released in cinemas. The first BBC2 showing, on 26 December 1975, had the stereo soundtrack simultaneously broadcast on Radio 3. The BFI have previously released The Magic Flute on Blu-ray.

Another miniseries followed. Face to Face was a four-part serial starring Liv Ullmann as Dr Jenny Isaksson, a psychiatrist undergoing a nervous breakdown. 177 minutes in total, it was reduced to 114 minutes for cinema release. This time, it wasn’t deemed ineligible by the Academy, who gave nominations to Ullmann as Best Actress and to Bergman as Best Director.

However, things soon changed. On 30 January 1976, Bergman was arrested and charged with tax evasion. The charges were dropped, but Bergman suffered a nervous breakdown as a result, to some extent feeling that he had been victimised because of his fame. He closed down his studio on Fårö and left the country, settling in Munich and vowing never to make a film in Sweden again. His next film, The Serpent’s Egg, was his second (and final) English-language film, shot in Germany and set against the rise of Nazism. Produced by Dino de Laurentiis, it’s one of Bergman’s darkest films and certainly his most explicitly violent, you wonder to what extent coloured by his circumstances. It was made on a larger scale, in studios in Bavaria, with Bergman’s direction favouring medium shots and crowd scenes far more than his usual emphasis on close-ups.

Eva (Liv Ullmann) has not seen her mother Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman) for some seven years and invites her to stay. Charlotte has had a long career as a concert pianist, travelling over the world. But when she arrives at the home of Eva and her husband Viktor (Halvar Björk), she is shocked to see that her other daughter Helena (Lena Nyman), disabled and paralysed, is there, with Eva caring for her. Soon mother and daughter are in conflict.

Of the films Bergman made away from Sweden, Autumn Sonata (Höstsonaten) is the most obviously Bergmanesque. However, it was made with West German and British (Lew Grade’s company ITC) money and shot in a studio in Oslo, with dialogue in Swedish (with some English) and a mostly Swedish cast and crew. Ingrid and Ingmar Bergman had a previous shared title in their filmographies, Stimulantia, but in different segments. This was the only time they worked together. Ingrid had long wished to work with her famous namesake (they were not related), also to work in her native language again, and this was the result. Autumn Sonata was her final film.

Although Viktor begins the film by breaking the fourth wall and conveying the necessary exposition to the audience, he takes a back seat to the strife between his wife and his mother-in-law, which culminates in a long confrontation scene. It’s not hard to detect some autobiography on Ingmar Bergman’s part: he had by his own admission not been a good father to his children, letting his work (and huge workload) take precedence. In Autumn Sonata, he examines this to some extent, though as was often his habit making his surrogate in the film a woman rather than a man – and a musician rather than a film director. (I wonder if that’s a comment either on Bergman’s love for music when he could not himself play an instrument as far as I know, or on the rarity of women directing films at the time this one was made.) While Ingrid Bergman is forceful in her role, Ullmann matches her, all hunched shoulders and submissive gestures, a woman who has taken being a wife and a mother as her goal, a far more thankless task than her mother’s career. Yet there’s a frustration built up inside her, and it gets a chance to explode. Both Bergmans were Oscar-nominated, for Best Actress and Best Original Screenplay respectively.

In 1969, Bergman directed his first feature-length documentary, Fårö Document (Fårö-dokument). Just under an hour long, it premiered on Swedish television on 1 January 1970. The film is a portrait of the island Bergman had made his home, with a population in three figures, having declined over the last half-century. The film makes the point that the islanders are disadvantaged compared to urban Swedes, with schools underfunded and nowhere for youths to go, and the island is overrun by holidaymakers in the summer.

That film is not included in this box set, but its ten-years-later follow-up, Fårö Document 1979 (Fårö-dokument 1979) is. Sven Nykvist had shot the original film, but didn’t return for this one, cinematographic duties given to Arne Carlsson, who had been Nykvist’s assistant ten years previously and frequently acted as Bergman’s stills photographer, and who was a Fårö native. However, some of Nykvist’s work is in the new film, in a sequence possibly inspired by the then-ongoing Up series made for British television by Michael Apted, in which a group of schoolchildren on a bus (in black and white) are asked what they see their future to be, intercut with new footage (colour) of how their lives have turned out in ten years. The film has a cyclical structure, taking in all four seasons, including the tourist season of summer and autumn where pigs are slaughtered and trees chopped down. Bergman limits his voiceover, mainly letting the images speak for themselves. At the end, Bergman suggests returning in a further ten years to see how the life of this island and these people have developed, but that film was never made.

FROM THE LIFE OF THE MARIONETTES |

|

From the Life of the Marionettes (+) begins startlingly, as businessman Peter Egermann (Robert Atzorn) murders prostitute Katarina “Ka” Krafft (Rita Russek) and then, fortunately for us offscreen, has anal sex with the corpse. Then in a series of scenes introduced by text captions, we see both before and after the crime. Psychiatriast Mogens Jenson (Martin Benrath) tries to find out the causes of Peter’s actions.

Like The Serpent Egg, From the Life of the Marionettes sees Bergman working outside his native language (this time in German) with results quite unlike much of the rest of his work and considerably darker too. (While many of Bergman’s films were adults-only on release, these two are the only ones which still have 18 certificates in the UK.) The film was made for West German TV and shot in Munich, with a cast of mainly theatre actors. While Bergman and Sven Nykvist’s use of closeups is present and correct, the film is a lot more dialogue-heavy than many of Bergman’s works, with many of the scenes two-handed conversations, and given the predominance of classical music in his films, it’s a bit disconcerting to hear disco beats over the end credits.

The film also shows Bergman and Nykvist returning to the black and white they had not used since Shame, just over a decade previously. However, the film begins and ends in colour, at the request of the television company, who feared that an all-black-and-white film would be uncommercial. The colour sequences are as dominated by red as other Bergman colour works, even down to the pair of knickers that’s almost all Ka is wearing. Then the colour fades away, to a black and white that’s more greyscale and less contrasty than other Nykvist/Bergman collaborations. (Was it shot on colour stock? I’ve not found out the answer to that, though it’s possible.)

Bergman was a heterosexual man who often returned to the subject of difficult if not fraught heterosexual relationships. Here we have another one, with Peter revealed to be dominated not just by his mother but by his wife Katarina (Christine Buchegger). (It’s not insignificant that both wife and murder victim have the same name). The result of this female dominance, Jenson suggests, is latent homosexuality on Peter’s part, a somewhat dubious proposition that rather dates the film. We also have a rare gay character in Bergman’s work, in Tim (Walter Schmidinger).

From the Life of the Marionettes, which was released to cinemas overseas, including the UK, had a mixed reception, and it’s not hard to see why. Peter is ultimately a puzzle to be solved, and the film is less than the sum of its parts. Perhaps being in exile from home, and with none of his usual collaborators (other than Nykvist and production designer Rolf Zehetbauer returning from The Serpent’s Egg) shows in what is an uncomfortable work.

By now, despite continuing to be based in Munich, Bergman had begun to work in Sweden again, with Fårö Document 1979 and work at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. However, he returned to his native country to make one more film for the cinema.

There are plenty of final films, final plays, final novels which weren’t intended to be. Because life, or death, or ill health or other circumstances interfered, they simply weren’t followed up, a final unresolved chord in their career. But there are others which were fully intended as swansongs, a summing-up by the now elderly artist of their work, their themes. The Tempest was Shakespeare’s, but the play of his that Bergman riffs off here is Hamlet. Fanny and Alexander is Bergman’s version of this, with many of his major collaborators on board for one last journey in cinema, and in television and theatre, the three media that Bergman spent most of his creative career. If Fanny and Alexander is the first two of these, it draws heavily on the third. The full version is subdivided into five acts, the first and last around an hour and a half with the middle three much shorter, plus a prologue and epilogue.

We begin in 1907, with the lengthy first act introducing most of the principal characters as the Ekdahl family celebrate Christmas. The youngest of the family are ten-year-old Alexander (Bertil Guve) and his younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin). All is well and good, but then their father Oscar dies of a stroke. Their mother Emilie (Ewa Fröling) remarries, to the local bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö) and they all move into house. However, Alexander soon clashes with the cold, authoritarian Bishop…

Bergman began writing Fanny and Alexander in 1980, while working on From the Life of the Marionettes. Now in his mid-Sixties, he decided that Fanny and Alexander would be his final film for the cinema, clearly feeling the strain of his long and prolific career up to that date. The film is clearly semi-autobiographical, and Alexander is in some respects an analogue of the young Bergman. That does not just include the toy theatre and the magic lantern he had been given as a child (he named his first volume of autobiography The Magic Lantern), but also the visions he saw as a child: a moving statue, an appearance by Death. Bergman many times described the coldness and abuse he received from his father, whom like Vergérus was a man of the church. However, this was disputed by his older brother Dag (still alive at the time), who said that he was the one who received the punishment from his father and his teachers, and Ingmar was the much-loved child. So, whether this is true and Bergman was guilty of self-reinvention, can now never be known, but you have to wonder if Ingmar’s actual stand-in is younger sister Fanny, standing aside and observing everything, not the first time that Bergman has given himself a female surrogate on screen. Despite her prominence in the title, Fanny is very much a supporting character.

Given the epic form he gave himself – in its full version, Fanny and Alexander is the longest film or television serial Bergman ever made – there is room to feature many different aspects of Bergman’s films. The first act has his humanity and humour on full display, while the darker and bleaker aspects of the story dominate the central acts. There are also aspects of the supernatural evident, in particular a late scene involving Isak Jacobi (Erland Josephson) and his attempt to locate the children.

Produced by Jörn Donner, Fanny and Alexander became the most expensive Swedish film ever made. Many of the actors who had worked with Bergman over his career returned. Two exceptions were Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann, who were originally intended to play Vergérus and Emilie. Von Sydow’s agent asked for a larger fee, so the role was recast. Von Sydow, apparently unaware of this, said he would have worked for Bergman at any price. Ullmann had a scheduling conflict so had to turn Bergman down, something she regretted and apologised for. The film ends with a nod to Strindberg’s “new” (published 1902, first performed 1907) A Dream Play (Ett drömspel), a favourite of Bergman’s, which he staged several times, once for television in 1963. We close with Emilie reading the lines, “Everything can happen. Everything is possible and probable. Time and space do not exist. On a flimsy framework of reality, the imagination spins, weaving new patterns.”

The full version of Fanny and Alexander runs five hours and twenty minutes, and was shown as a television serial – sometimes in as many as five episodes following the act structure (two longer ones bracketing three shorter ones). The BBC2’s first broadcast, over Christmas week 1984, showed it in three. The copy on this disc has four episodes with a Play All option, with Acts Two and Three making up the second episode (running times 95:44, 78:12, 60:06, 86:54, all including the same end-credits sequence and restoration captions). Bergman shortened the film to 189 minutes for cinema release, something he found difficult to do. I would agree with him, that the longer version is the definitive one, though both are available in this set. The film won four Academy Awards, for Nykvist’s cinematography, Anna Asp for her art direction, Marik Vos for her costume design, and for Best Foreign-Language film. Bergman was nominated for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay.

Fanny and Alexander, forty years after it was made, remains one of the great directorial swansongs on film, and is the capstone of one of the century’s great writing and directing careers.

Except it wasn’t the end.

After all the fanfare, the release, and then the awards, for Fanny and Alexander...another film. However, Bergman hadn’t broken his promise and made another cinema feature. This one was for television, premiering on Swedish television on 9 April 1984. It did have cinema showings outside Sweden, but appeared on UK television on BBC2 on 7 December 1984. (Fanny and Alexander followed on the same channel over Christmas week that year, the first time I saw it.)

After the grand scale of Fanny and Alexander, After the Rehearsal (Efter repetitionen) is a chamber work, shot in 16mm (Sven Nykvist still in place). The two main roles were filled by familiar faces: Erland Josephson and Ingrid Thulin. Lena Olin had worked for Bergman in Face to Face and had had a small role in Fanny and Alexander, but at this point in her career was mostly a stage actress. The cast is completed by two non-speaking child roles, as Josephson and Olin’s younger selves, played by Alexander himself, Bertil Guve, and Nadja Palmstjerna-Weiss.

Henrik (Josephson) is the director of a production of Strindberg’s A Dream Play. At the end of a day of rehearsals, he is sitting reflecting backstage when he is visited by one the cast, Anna (Olin). Anna reveals that her mother, Rakel (Thulin), whom we see in flashback, was Henrik’s former star and lover, but she loathed her due to her alcoholism…

Bergman’s stature is such that almost any of his films deserve their place in his filmography, but After the Rehearsal, ably made and as well acted as you might expect, remains a minor work. It did make some top ten lists for the year, however.

Bergman kept his vow not to direct for the cinema again, but he continued to write for other directors. The Best Intentions (Den goda viljan, 1991) was directed by Bille August as a miniseries and a shorter (but still three-hour) cinema version. The latter won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Sunday’s Children (Söndargsbarn, 1992) was directed by Bergman’s son Daniel and Private Confessions (Enskilda samtal, 1996) by Liv Ullmann, a two-part miniseries shown in a shorter version at festivals. These three films were all inspired by the lives of Bergman’s parents. Finally, Ullmann directed his script for Faithless (Trolösa, 2000). Meanwhile, Bergman did direct again for television – The Blessed Ones (De två saliga, 1986), which reunited him with Ulla Isaksson, who wrote the script. In the Presence of a Clown (Larmar och gör sig till, 1997) was based on his own play, while The Image Makers (Bildmakarna) was based on the play by Per-Olov Enquist about the making of the silent classic The Phantom Carriage, which had been directed by Bergman’s mentor Victor Sjöström. Bergman’s final film was Saraband (2003), made for television but receiving cinema releases abroad, a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage, with Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann returning to their roles. In the same year, he directed his final stage production, Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. He retired completely at the end of that year.

Ingmar Bergman died in his sleep on 30 July 2007, at the age of eighty-nine. If it was the end of an era it seemed even more so given that another major figure of European cinema, five years older but who had also come to prominence around the same time, Michelangelo Antonioni, died on the same day.

Ingmar Bergman Volume 4 is a six-disc Blu-ray set encoded for Region B only. It comprises one BD-25 (Disc One) and five BD-50s: Cries and Whispers is on Disc One, Scenes from a Marriage on Disc Two, then Autumn Sonata and Fårö Document 1979 on Three, From the Life of the Marionettes and (breaking chronology) After the Rehearsal on Four, and the theatrical and television vcrsions of Fanny and Alexander respectively on Five and Six.

The set carries an 18 certificate, which is due to From the Life of the Marionettes (an X certificate in cinemas). Cries and Whispers was also an X in cinemas but is now a 15. Scenes from a Marriage and Autumn Sonata were AA (fourteen and over) in cinemas but are now 15, while Fanny and Alexander and After the Rehearsal, both released after the BBFC changed their certification system, the latter first on DVD in 2006, have always been rated 15. Fårö Document 1979 is a documentary and has been exempted from classification.

As mentioned above, all of these films were made after Bergman adopted widescreen and are in a ratio of 1.66:1, with two exceptions. Scenes from a Marriage, shot in 16mm for television, is presented in a ratio of 1.37:1, which is certainly the one television viewers, but there is enough room at the top and bottom of each shot to support cinema projection in 1.66:1 without the film looking unduly cropped. Fårö Document 1979, also shot in 16mm, is also 1.37:1 but that’s not unexpected for a documentary mostly shown on television. The restorations were based on 2K scans using the camera negatives (16mm for Scenes, 35mm for the others) except Fårö Document 1979, which is from a colour reversal intermediate negative and dupe negative. After the Rehearsal was supplied in standard definition and has been upscaled to 1080p. The 16mm-sourced films are inevitably softer and grainier, particularly After the Rehearsal, but is present and filmlike on the 35mm HD-transferred ones. Colours register strongly, especially the reds on the two films which Sven Nykvist won his Oscars for.

The soundtracks are the original mono in every case, and are clear and well-balanced. English subtitles for these Swedish-language (or in one case German-language) films are available as the default and are optional.

With hybrid material like this, films made for both television and cinema, the question of intended speed comes up, as Swedish television used the PAL system so would have broadcast films at twenty-five frames per second (fps) instead of the cinema sound speed of twenty-four. This would have the effect of making the film run short at a rate of one minute in every twenty-five, and will raise the pitch of the soundtrack by half a semitone. That’s a particularly good question with The Magic Flute, given that it is a filmed opera. The BFI’s Blu-ray is 24 fps but as I don’t have perfect pitch nor am intimately familiar with the music, I couldn’t tell if that was the right speed or if it had been slowed down. For the record, all the films in this set are presented at 24fps. I can be certain that From the Life of the Marionettes was shot at 24fps as at one point there is a shot of a television set with rolling bars.

Trailer for Cries and Whispers (1:31)

Trailer for Fanny and Alexander (1:38)

The only on-disc extras are these two trailers on the appropriate discs, One and Five respectively. These aren’t the original trailers but ones for the BFI’s recent cinema reissues, so critics’ quotes and mentions of Academy Awards are included.

Book

Adding considerable value to this set is the BFI’s book, available on the first pressing only, running to ninety-six pages. There are spoiler warnings included. It begins with “Of Wordless Secrets: Cries and Whispers” by Geoff Andrew, which starts on a very autobiographical note. Andrew saw the film as an undergraduate at the urging of a friend. At that point, the only subtitled films he’d seen had been on BBC2. The film changed his life and he suggests that if he hadn’t seen it, or another film hadn’t fulfilled the same function, he might not have had the career as a film critic he has had for fifty years now. He goes on to discuss the film itself, examining how it had the crossover success it did, given its on-the-face-of-it thoroughly uncommercial subject matter.

In “A Love Song to Divorce”, Catherine Wheatley looks at Scenes from a Marriage, which she sees as a hopeful film, even though it depicts a supposedly perfect marriage coming apart, at times violently. “Duet for Three” by Leigh Singer tackles Autumn Sonata, concentrating on the dynamics on set between the writer-director and his two star actresses. Geoff Andrew returns to cover Fårö Document 1979, while Andrew Graves finds From the Life of the Marionette oppressively difficult and uninviting, perhaps intentionally so. Philip Kemp looks at Fanny and Alexander, covering the making of the film, the differences between cinema and television versions and its reception. Finally, Ellen Cheshire discusses After the Rehearsal, and her essay sums up the differing reactions to the film, “A Travesty of a Work of Greatness?” Also in the book are credits for each film, transfer notes and stills.

The BFI’s four Ingmar Bergman Blu-ray sets comprise thirty-two films (counting the different versions of Fanny and Alexander as two). Bergman’s work rate has been mentioned before – the documentary Bergman: A Year in the Life (also on a BFI Blu-ray) looks at what he did in just one year, 1957 – and those thirty-two are just under half of what he made for cinema and television and that’s not counting 171 stage productions. I’ve written my four reviews so that they can be read as one long one, with mentions of films not in the sets at the appropriate places. Some of those are major titles which for reasons of rights ownership are not included in these sets. If you don’t own many or most of these films, these four sets are essential in the career of one of the great writer-directors in twentieth century cinema.

|