| |

"Though wreathed in official awards, A Man for All Seasons has emerged as an anti-auteurist landmark, partly due to its disreputable genre, the costume biopic embodying the Great Man model of history, while alternating high-minded rhetorical debates with domestic squabbles." |

| |

Senses of Cinema's Robert Keser on Fred Zinnemann's A Man for All Seasons * |

This attitude, harsh though it may seem, may well be why this excellent adaptation of Bolt's stage play, languishes somewhat in the 'not quite as well known or seen' pool. This is rather unfair. And one of its champions proves that people can still surprise me. There is a rather excellent book of interviews by Robert K. Elder in which he asks thirty-five directors which forgotten or critically savaged films they love. A Man for All Seasons, in the UK at least, is neither forgotten nor critically lambasted. Of its six Oscars, three were the top three, Best Film, Best Actor and Best Director. This is a movie with a treasured pedigree but the director that champions this film as 'lost' in terms of his own generation, may have a point. His defence of it was so heartfelt and so enthusiastic, Elder elected the interview worthy of inclusion despite Seasons' Oscars. What surprises me is the identity of the director who had such a passion for what is essentially a conventionally directed talk-fest with extraordinary performances and an amazingly cultured and polished screenplay.

Playwright Robert Bolt adapted his own play and in some respects could lay claim to being England's Paddy Chayefsky of his day (as mentioned by Julie Kirgo on the commentary). You know you are not hearing the words of ordinary men but words that have been honed and rewritten and thought profoundly about. The director-fan in question is none other than Kevin Smith, the Clerks director, Silent Bob himself. More famous today as a podcaster and pop culture commentator, his defence of Seasons is rabid and uncompromising. There is arguably nothing in Smith's oeuvre (with the exception of a 'Special thanks to' credit for Robert Bolt at the end of Smith's Dogma) that points to a passion for this film but I applaud him for surprising the hell out of me. We're all judgemental to a degree but it pulls me up short to have blithely thought that Seasons could not be appreciated by the man who gave us Zack and Miri Make A Porno. More fool me. I felt a degree of this stupidity when Charlotte Church popped up on the BBC Radio 4 science show, The Infinite Monkey Cage. This outspoken, Welsh singer could wax lyrical about quantum physics. Who knew? These incidents show how dumb and dangerous my assumptions can be. Given this, it's still a surprise to hear lines like the following in appreciation of this formal and somewhat classic film... Smith said that it was 'porn for someone who loves language,' and specifically in Elder's book, he adds to this with "...every line of dialogue is a close up jizz shot to some degree or a really great close up on double penetration." It's a... (ahem) unique take on this lauded work (can't recall too many reviews out there presented in the idiom of hard core porn) but, for my many sins, I do know exactly what he means.

Despite its near invisibility in popular culture, Seasons is a great movie and the very last thing I would do is be disrespectful towards it but if its narrative is broadly historically accurate, it really boils down to (as newspaper 'Ye Sun' may have put it at the time) 'Horny King can't have his way because of Catholic beliefs so breaks off from the faith, realigns the entire country's religion which is now under his command and has one famously religious adherent in his court pay the ultimate price for staying true to God' – or something not too unlike that. It says a great deal about how strong a hold religion had in those days of the 16th century. The truth, however we classify that precious commodity these days, was probably infinitely more complex than that but history, like movie adaptations, tends to boil events down to the salient and important moments that events turn on. It's apparently true from most reputable sources that Henry VIII was anxious to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and take up with his mistress's sister, Anne Boleyn. But under Catholic law, divorce was a sin. It's a needlessly complex matter but Henry was very determined, led by hormones and desperate for a son and heir, so eventually he selfishly overturned the entire religious machine of England at that time just to get his way. Kings could do stuff like that with a little help from their acquiescent acolytes.

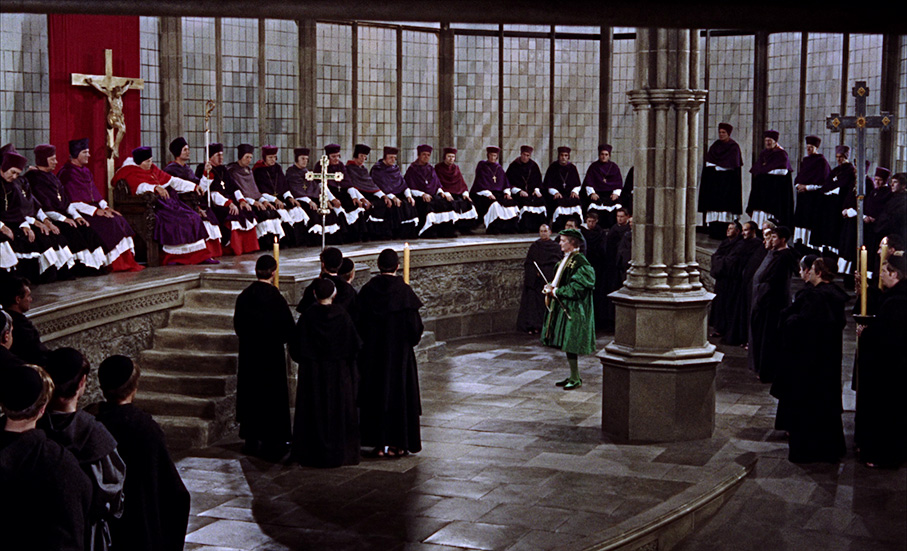

So, to the plot of the movie; the corpulent and sick Cardinal Wolsey (Orson Welles) summons Sir Thomas More (Paul Scofield), a member of the Privy Council. The powerful cleric wants to please his king and make it easier for Henry to do what he wants by changing the religious laws. Sir Thomas More places great stock in his religion and is unbending towards his decisions borne of a clean conscience and morally pure relationship with God. Earlier that day he voted against Wolsey in court believing politics and even the king were not above God's judgement. While this makes Sir Thomas essentially incorruptible, it also places him in the way of some very powerful men with powerful desires, both personal and political. The man who keeps all these pieces on the board in check (or not) is King Henry VIII played with a gutsy, lustful exuberance by a youthful Robert Shaw. He wants all of his courtiers to fall in line and sign an oath to allow him to annul his first marriage and change the religious face of the entire country cutting it off from Vatican control. This is something Sir Thomas More simply cannot do out of conscience. He renounces his new responsibilities as Lord Chancellor. This sets up a fateful chain of events, a fall from grace that More still believes he can avoid by placing his faith in the law of the land. More's fortunes take a turn for the worst and friends and family are adversely affected. His stubborn but logical silence on the subject even and especially towards his nearest and dearest is absolute. He's a lawyer. He knows that if he stays quiet none of his acquaintances can be forced to speak of his attitudes. We only realise the depths of his feelings on the matter of the king placing himself ahead of God once More's tried and sentenced. A betrayal prompts the most quoted line in the film and I suspect the dig at the Welsh would never have been seen as racist. It's just Wales after all. Anti-Welsh sentiment is never taken seriously (I say this as a bona fide, Cardiff born, sensitive soul... right). An old friend has perjured himself for advancement and finds himself Attorney General of Wales... More says "Richard, it profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world, but for Wales?" That's a seriously classy put down. You're not coming back for more (or even More) after a line like that. And yet the traitorous bastard was the only player in the great game to live a long life. Life is seldom fair.

Director Fred Zinnemann, a curious and lauded filmmaker with a plethora of worthy films to his name, is smart enough to stay out of the way and let the play do the talking. The director of High Noon, The Day of the Jackal and From Here To Eternity, lets the low budget dictate the style of the piece and all kudos to production designer John Box who managed to make everything look suitably opulent and concise often creating sets and partial sets to take advantage of the chosen locations. The craft on display is worth celebrating and all the crew and cast seem to be revelling in the earnestness of the production. Its cast is a celebration of nascent English talent, talent that went on to carve out great international careers. There's John Hurt as Richard Rich, the afore mentioned bastard, excelling in weak men of dubious morality. Susannah York is radiant and Latin-quoting smart as More's daughter. The marvellous Wendy Hiller plays More's wife, a lion in character and then there's Leo McKern as the duplicitous Cromwell, a year away from his stint as No. 2 opposite Patrick McGoohan in TV's The Prisoner (I loved those performances, such an interesting actor). The lesser parts are peppered with familiar faces... Nigel Davenport, Vanessa Redgrave (doing a free favour for a beloved director), Colin Blakely, even Yootha Joyce, famous from the ITV sitcom Man About The House.

Bolt's writing talent extended to a depth of characterisation unheard of in modern movies. In an early scene, Orson Welles assures Scofield that there is no one else in the room so he can speak freely. Scofield bats this back with a masterful throwaway "I didn't suppose there was, your Grace." Welles replies with a shocked, mumbled "Oh!" Welles' monstrous Cardinal is caught beautifully, a scheming spider aware that most can see the silken strands. In assuming there is no web, Scofield gets Welles to admit his own treachery. Just wonderful. Scofield's More, with his God-given honesty and wit, dispenses effortless critiques artfully disguised by good manners and a soft cadence. In all of cinema, I can think of no actor who could have pulled off this role with such gentle and sustained conviction. This isn't to say his character is faultless, far from it. To be so convicted has both its pros and cons. What a tragedy to be so respected for the one trait that incapacitates Scofield's ability to please the man he was honour bound to serve. This is a conflict and a tragedy.

This isn't to say there are no laughs to be had. King Henry's enthusiasm for music and subsequent conversation with More is a joy and there's a lovely moment when More's daughter goes to stand up in the presence of the king as he turns away from her. More's hand gently presses her head down so she sinks back to her knees emphasized by a beautifully timed cut (Ralph Kemplen, take a bow). But there is also a truly heart-breaking moment that hits you after the event. At his wedding, King Henry thinks he glimpses his friend, Sir Thomas. He shows his genuine love, friendship and relief by running through the crowd calling his name out. It turns out not to be Sir Thomas (though I suspect it was actor Scofield shot from behind in the wide shots) and the disappointment in Shaw's face is palpable. Friendship is also tested in more subtle ways. More's relationship with the Duke of Norfolk (a manly Nigel Davenport) has to be soured, and publically witnessed to be so, because that friendship will damage Norfolk by association. All More can do is question the purity of Norfolk's line of great British bulldogs. It's enough to drive a faux but necessary wedge between the two friends, a wedge both men know is manufactured for the cheap seats...

I'll conclude by acknowledging an aspect of 16th century society that is so difficult for a 21st century person to grasp. God, then, was as real to the sophisticated mind as it was to the uneducated so you have to look past the logic of Kevin Smith's wife who finds it ludicrous that a man would "widow his wife and orphan his child" for the sake of appeasing a fictional deity. It was oh so real to these people. Despite Brexit and Trump, I am thankful, very thankful that I live in a largely secular country though things can change and have rather dramatically. A Man for All Seasons is warmly and enthusiastically recommended.

A Man for All Seasons was always a visually attractive film, but the transfer on the Blu-ray in this Masters of Cinema dual format release is as good as I’ve seen it look. Framed in its original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, the image does sometimes feel a little flat, though I suspect this is primarily down to the cinematography, which tends to favour a more naturalistic look and does not make extensive use of rim-lighting commonly used to pull actors out from the background. Occasionally there is a sense that the brightness has been dialled down a notch from previous home video incarnations, but the image is consistently and impressively sharp, with a sometimes excellent level of detail visible on costumes and sets, the contrast is punchy but not over-aggressive, and while the palette is sometimes on the warm side, brighter colours are vividly rendered. When the elements all come together, as when Henry and his court arrive on their boats at Thomas More's estate, the picture really shines.

The original mono soundtrack is included as a Linear PCM 1.0 track, which is clean and reasonably clear, but there is also a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround remix, which is superior in every respect, having more volume, greater clarity and – especially evident in Georges Delerue’s regal music score – a considerably livelier dynamic range.

There is also a Linear PCM 1.0 mono music and effects track for those who enjoy that short of thing.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with writer/film fan Lem Dobbs, documentary filmmaker and record producer Nick Redman, and Julie Kirgo, Twilight Time's essayist.

There is nothing quite like spending a few hours with people who know their stuff. Yes, all three may have been sitting in front of microphones and lecterns full of notes but with the exception of stating that Leo McKern was British (he was an Aussie), everything just feels right and I very much wanted to join the conversation.

The three-way conversation covered many topics as the film's scenes prompted them. There's the Thames, the 'freeway' of England at that time. Vanessa Redgrave played her part for no fee out of love for the director and Wendy Hiller is praised and her greatest film advertised and promoted. Perhaps I need not say what this was but be sure I have reviewed it. Oh, go on then, it's I Know Where I'm Going. John Hurt gets a mention (always playing weakness which I didn't quite agree with) and Robert Shaw is praised and his agent's biography championed. It is said that Britain is a nation of shopkeepers but also schoolteachers apparently. We are reminded that John Cleese was a schoolteacher and maintained that profession's persona for a long time in his comic performances. The trio muse on historical tides sweeping characters aside and there's a brief appreciation of Leo McKern.

Kirgo mentions that a cut in Seasons is as memorable as the famous cut in Bolt's other written screenplay, Lawrence of Arabia. Not quite. Sir Thomas More promises that if he is able, he will find a way to sign the oath on his own terms but the next scene follows swiftly – More in the tower. It's not a cut by the way. It's a mix. We are reminded that refined sugar had not conquered the world at this time in human history so good teeth were perfectly acceptable historically in this film. Finally, there's a certain poignancy at the three talking about how John Hurt is one of the few still alive associated with the production at the time of the recording. I have only one word...

Alas.

The Life of Saint Thomas More (18:16)

An older piece (the 4:3 framing and non-HD image quality give it away) in which Alison Weir, Dr. John Guy and Dr. Gerard Wegemer explore the life of Thomas More and his fateful conflict with Henry VIII. Personally, I learned quite a bit from this.

Neil Sinyard (31:25)

Film historian and Masters of Cinema regular Neil Sinyard, photographed against what looks like a hospital curtain, takes the reverse route to usual for such pieces by talking about the film for the first half and then exploring director Fred Zinnemann’s career in the second. Both are enthralling and peppered with interesting anecdotes, from the four films that convinced the young Zinnemann that he wanted to be a filmmaker to his insistence on casting Paul Schofield as Thomas More, despite studio pressure to go with Laurence Olivier. Some of the film’s underlying themes are examined, and Sinyard makes a persuasive case for the re-release of Zinnemann’s The Search, a 1948 film with a contemporary ring about the fate of child refugees fleeing war zones.

Original Theatrical Trailer (3:19)

A rather stiff American trailer that gives little idea how damned fine a film this is, framed 4:3 and in standard definition, but free of damage and dust.

Also included is the expected and typically well produced Masters of Cinema Booklet, the bulk of which is occupied by a scholarly essay by James Oliver on the film and its production and reception. Also included are a number of production and archive stills, credits for the film and the usual notes on viewing.

A captivatingly written, directed and performed true story of faith and principled defiance in the face of impossible odds that genuinely belies its modest £600,000 budget. The disc may not be overloaded with special features, but all are well selected and most worthy inclusions, and the transfer and surround remix showcase the film impressively. Recommended.

|