|

– PART 2 –

| "It's very good to steal things. Bertolt Brecht said art is made from plagiarism." |

| Jean-Luc Godard |

| Things Are There. Why Manipulate Them? |

|

In an interview with Cahiers du cinéma soon after the release of Le Mépris, Godard said of Alberto Moravia's source novel Il Deprezzo (A Ghost at Noon), 'I have stuck with the main theme, simply altering a few details, on the principle that something filmed is automatically different from something written, and therefore original' (a comment uttered, almost verbatim, by Lang in the film). He also contemptuously dismissed Moravia's novel as 'a nice, vulgar read for a train journey' and cuttingly suggested that 'time trying to discover the language of Proust beneath that of Moravia' was lost time. Moravia became equally contemptuous of Godard and begged François Truffaut to take over from Godard and direct the adaptation of his novel. Without telling Godard, Truffaut refused. [I wrote about Truffaut's friendship with Godard when reviewing Emmanuel Laurent's Deux de la vague on this site and wish I'd noted that touching act of loyalty. It makes the collapse of their friendship more tragic. Before long Truffaut would be calling his old friend ''The Ursula Andress of militancy, like Brando, and a piece of shit on a pedestal.'

We can but wonder what aesthetic or personal differences soured Godard's dealings with Moravia. Wonder too, what he might've made of Moravia's above-mentioned La Noia (Boredom), the story of a pampered bourgeois dilettante who attempts suicide after becoming infatuated with a young model. Whatever the reasons for the feeling of mutual contempt between Moravia and Godard, the novel generated the script demanded by the film's producers. For once, Godard, the improvising iconoclast, may have needed the firm foundation of a script to hold things together, because his relationship with Anna Karina was unravelling at precisely the moment his love affair with Hollywood was on the rocks. Godard worked with what was in front of him. He worked life into his films and life worked his way into them. As his great idol Roberto Rossellini said, 'Things are there. Why manipulate them?' Godard might have nodded agreement, but he might equally have paused for thought and replied, why not?

The material of Godard's own life worked its way into the his films. Take the loss of his mother, Odile Monod, who was killed in a crash on her Vespa near Lausanne in 1954. Prior to that event, Godard's relationship with his mother had intensified just as that with his father had soured (partly because of Godard's kleptomania, particularly after Godard was caught and jailed). This one tragic moment is replicated at the end of Le Mépris, in Weekend, and in many of his other films. In Weekend a Shell Oil truck is stuck in a nose-to-nose stalemate with a Fiat headed in the opposite direction on the same stretch of road. As David Serrit says, 'This is a prototypical Godardian symbol, transforming the personal car crash that climaxed Le Mépris into a socioeconomic car clash (Shell vs. citizen).' Never mind 'a girl and a gun', what about the cars?

In Le Mépris, Godard's disintegrating relationship with Anna Karina is reflected in the psychosexual drama at its heart. Karina regularly visited Godard in Rome while he was shooting Le Mépris but all was not well. In an interview with Richard Brody for his compendious and useful book Everything is Cinema, Karina says, 'It was mad love. Love, jealousy, revenge. We adored each other. We were rather passionate. We had crises of jealousy. Oh, there were some slaps. In Rome we went to nice nightclub one evening, someone invited me to dance, I went, and when I came back, [Jean-Luc] slapped me in the face, in front of everyone . . . But I wasn't angry – it was proof of his love.' Karina's chilling closing remark hints at the violent edge to her relationship with Godard and the dark aspects to their respective personalities, both of which cast a disquieting shadow over the film.

Le Mépris is a microscopic and scintillating study of a disintegrating marriage, but it is also marked the first awakening of Godard's nuanced anti-Americanism and defence of European cinema. Camille/Bardot and Paul/Piccoli, simultaneously embody Godard's imploding relationship with Karina and the French New Wave's challenge to Hollywood hegemony. This compacted palimpsest also operates as an equally forensic survey of the collapse of the Hollywood studio system, one in which Godard's conflicted cinephile feelings play out in the characters of Lang and Prokosch – who also reflect Godard's declared commitment to act as 'a mirror in which America will watch itself from morning till night, appalled by its own ugliness, delighted by its beauty.' He once said that the main achievement of the New Wave was to have established a new country on the map of the world – and the name of the country was CINEMA!

Peter Bogdanovich suggests that Fritz Lang was driven from the U.S.A. by producer interference in his Hollywood films. Their loss was Godard's gain. To Godard and the critics of Cahiers du cinéma Lang, 'the man with the adagio camera', was, as he is in Le Mépris, the living embodiment of Hollywood's heyday – the man who had acknowledged his debt to popular comic-strips and insinuated Weimer-era Expressionist tropes into Film Noir. The Cahiers' critics argued that Lang's Hollywood films (The Big Heat, Human Desire, Rancho Notorious) had as much claim to greatness as his German classics (Metropolis, Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, M). Godard alludes to this theoretical position in Le Mépris: when Paul introduces Camille to Lang. Camille tells the German that Rancho Notorious was terrific while Lang says he preferred M.

| Light – Camera – Quotation |

|

To Godard himself, Lang was also, importantly, the man who had worked with Bertolt Brecht on Hangmen Also Die. Not even Godard ('God Art') could persuade Brecht to return from the grave to appear alongside Lang in Le Mépris but Godard's film-within-a-film is a Brechtian distanciation device if ever there was one. Lang quotes a stanza from Bertolt Brecht's Hollywood Elegies in the: 'Every morning, to earn my bread/I go to the market where lies are traded/In hope/I take my place amongst the sellers.' Chris Marker said that a young Communist friend of his had become incredibly excited by Lang's double-edge reference to 'Our B.B.' (Bertolt Brecht/Brigitte Bardot), seeing it as a symbolic manifestation of a future reconciliation between the old revolution (political and industrial) and the new revolution (moral and cultural). Be that as it may, it seems somehow symbolic that the closest Godard came to death before death was during his near-fatal motorbike accident in 1971, when he was rushing to a bookshop to buy a book by Brecht.

Godard's love of Hollywood was present in his work from the start. Peter Wollen again: 'The dedication of Breathless to Monogram Pictures, the loving tributes to hard-boiled movies that never even made it to cult status, were part and parcel of a coherent and considered re-evaluation of classic American cinema.' The headline above Variety's report on the 1959 Cannes festival read, 'Boy Directors, Some Ex-Critics, Dominate Entries at Cannes.' Just before that edition of the festival opened, Godard wrote in the magazine Arts, 'We have won by getting the principle accepted that a film by Hitchcock is as important as a book by Aragon. The auteurs of film, thanks to us, have entered definitively into the history of art.' Aragon would later repay that compliment with interest: while working as Editor of Les Lettres françaises he wrote a 'Homage to Jean-Luc Godard': 'I've seen a novel of today, at the cinema. It's called Le Mépris . . . the novelist is someone called Godard. The French screen has seen nothing better since Renoir, when Renoir was the novelist Jean Renoir . . . We've been asking for genius – well here is genius.'

Godard filmed in quotation marks. As David Thompson says, '[He was] the first filmmaker to bristle with the effort of digesting all previous cinema and to make cinema itself his subject.' His entire delicious oeuvre was marinaded in and seasoned with cinephiliafrom the start. À bout de souffle might be a sequel to Otto Preminger's Bonjour Tristesse – which appeared in Godard's Top Ten films of 1958 alongside Joseph L. Mankiewicz's The Quiet American. In his dazzling debut feature Godard used Jean Seberg, who had starred in Preminger's film, saying 'I could have taken the last shot of Bonjour Tristesse and started after dissolving to a title: 'Three Years Later.' Three years after À bout de souffle, Godard used Giorgia Moll, one of the leads in Mankiewicz's, saying, 'Each of the characters . . . speak their own language which, as in The Quiet American, contributes to the feeling of people lost in a strange country. In another town, wrote Rimbaud.'

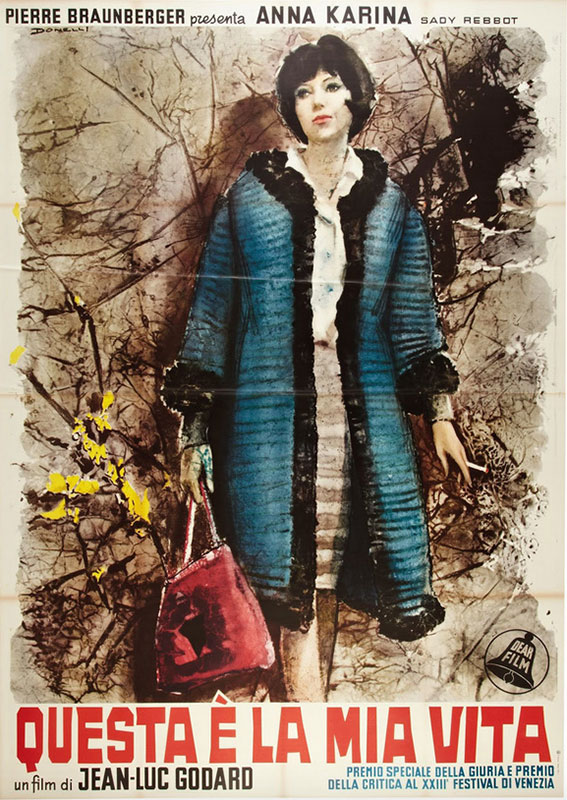

In Le Mépris Georgia Moll plays Francesca Vanini, Prokosch's assistant, who has the thankless task of interpreting the often-inscrutable comments uttered by the film's principal characters as they move between English, French, German and Italian. Petted, patted, which is to say sexually assaulted by both Paul and Prokosch, Francesca's presence complicates relations between Camille and Paul. Her surname is a nod to Rossellini's Vanina Vanini. Rossellini was the director for Godard. The so-called 'Hitchcocko-Hawksians' of Cahiers du cinema might have more accurately been called the 'Rossellinians' or the 'Rossellini-Wellesians.' There are four film posters on the walls in an early scene at Cinecittà: Rossellini's Vanina Vanini and Godard's Vivre sa vie are sandwiched between Hawks's Hatari! and Hitchcock's Psycho. Given Godard's attention to detail, it is unlikely that the placement of those posters was accidental. At any rate, they graphically represent the split between European cinema and Hollywood while advertising the predilections of the Cahiers' 'Hitchcocko-Hawksians'. They are also a few of Godard's favourite things: three of those films appear in Godard's list of the Ten Best films of 1962, the remaining film, Psycho, appeared in his list for 1960.

It is worth labouring the frequently made point about Godard's predilection for quotation to note, as Laura Mulvey does in Afterimages, that Lang and Palance operate, in Jacques Aumont's memorable phrase, as 'living quotations'. So too did Jean-Pierre Melville in A bout de souffle, Jeanne Moreau in Une femme est une femme, Sam Fuller in Pierrot le fou, and so on. Le Mépris is most obviously Godard's salute to Viaggio in Italia, Rossellini's story of a collapsing marriage. It is a homage to and remake of Rossellini's film just as surely as Les Carbiniers was to and of Rossellini's imperishable War Trilogy. When the central characters watch when they go to the cinema, in Le Mépris it feels almost inevitable that they will watch Rossellini's film.

Godard and the other young punks of Cahiers, soon to become the Young Turks of the New Wave, had steered a course between the anti-Americanism of the French Communist Party (with its 'natural' preference for Soviet cinema) and the French establishment (with its uncritical devotion to cinéma du qualité) by fervently embracing Hollywood, even and especially those scorned B-movies that, as Andrew Sarris put it, were widely reviled and seldom, if ever, revived. They adored Hollywood almost as much as they loved Rossellini. Le Mépris is a lament for a lost Hollywood counterpoised with a homage to European cinema.

Much of the film's mesmerising force derives from its locations, most notably the Cinecittà studios complex, known as 'Hollywood on the Tiber', in which the film opens; and the majestic Case Malaparte on Capri, the cinematic sanctum in which the film's final third unfolds. As Godard says, 'An afternoon in Rome, a morning in Capri. Rome is the modern world, the West; Capri, the ancient world, nature before civilisation and its neuroses.' The existential emptiness at the heart of civilisation and the central characters' lives is emphasised by Godard's treatment of the locations: his characters wander through deserted and dilapidated sandy lots at Cinecittà, and around crumbling Casa Malaparte, long battered by the elements. Built contemporaneously, with tainted Fascist coin, these historically significant and compromised locations reinforce the film's metaphorical foundations. As surely as Bardot and Piccoli, Lang and Palance operate as living quotations, these two locations operate as signifiers, if not characters in the film. Godard's first (self-financed) film, Opération béton, concerned a construction project and in his BFI video essay, Jean-Luc Godard as Architect', Richard Martin suggests that Godard was as interested as Antonioni in the built environment and urban space, witness the way Le Mépris moves from the 'dilapidated lots of the Cinecittà flm studios on the outskirts of Rome to Capri's Casa Malaparte.'

All but obliterated by Allied bombing in the Second World War, the Cinecittà site was later used as a prisoner-of-war camp and then, after the liberation, as a holding camp for displaced people. The studio's dilapidated post-war condition contributed to neo-realism's preference for deployment of non-professional actors and shooting on location. After it was rebuilt, of course, it became not only the cradle of the golden age of Italian cinema, where Rossellini's Viaggio in Italia and De Sica's Umberto D. were shot, but also the locus of Hollywood in exile. Fellini's 8½ and Joseph L. Mankiewicz's Cleopatra were both filmed at Cinecittà in the same year as Le Mépris. As Laura Mulvey says in Afterimages, the Hollywood studio system had been under pressure ever since the Paramount Act of 1948 unpicked vertical integration and monopoly control. When it finally collapsed under the assault of television, it attempted to halt its terminal decline with spectacular 'sword and sandals' epics such as Mankiewicz's Cleopatra and spaghetti Westerns such as Sergio Leone's For a Few Dollars More.

The timely recent death of Silvio Berlusconi reminds us of the anti-democratic concentration of media control (in Italy, for example, by Berlusconi's Mediaset and in the U.S.A. by Murdoch's Fox) and the links between media ownership and political power. Luigi Freddi's surveys of Hollywood on behalf of Mussolini had formed the basis for Fascism's model of film production, part of the regime's self-legitimising project to distance itself from the brutal violence of Squadrismo and the blackshirts who formed the model for Hitler's brownshirts.

Under Fascism's homogenizing dictates, all films were to be made in Italy by Italians. All foreign film companies were compelled to dub dialogue into non-accented, non-dialect Italian. The dubbing system and attendant dubbing surcharge, which survives largely intact to this day, generated a cottage industry that guaranteed steady work and dovetailed with Fascism's determination to erase local linguistic ecosystems. Against this historic background, Godard's decision to adopt the multi-lingual approach Mankiewitz had adopted in The Quiet American takes on added significance. We cannot know if it was intentional on Godard's part, but Georgia Moll's translations radically disrupts that historic dubbing process. As Peter Wollen notes in his essay on Vent d'est, that process meant meaning was lost in translation anyway, but Francesca Vanini is continually presented with meaningless remarks to speak.

Perched serenely, if precariously on an isolated promontory above the lapis lazuli blue of the Tyrrhenian Sea, Casa Malaparte was a wonder of its age and it stuns us still. David Serritt calls it 'one the most thrilling pieces of architecture not just in Godard's career but in the whole history of cinema.' It is hard to imagine Le Mépris without Casa Malaparte. If Bardot and Piccoli, Lang and Palance, Moll and Godard himself operate as living quotations in the film, this extraordinary building acts as the film's exclamation mark and full-stop. There is something darkly mythic about it, as if its contaminated origins had seeped into its brickwork like the briny spume that worked away at its surface, something that perfectly suits the film's admixture of shadowy original sin and brilliant beauty. Described by Bruce Chatwin as 'a Homeric ship gone aground,' this imposing edifice enabled Godard to push off from Moravia's modern tale of marital tragedy and relocate his meditations on dirty money in the poetic realms of Greco-Roman legend.

Casa Malaparte's creator, the diplomat-filmmaker-writer Curzio Malaparte, bought the plot of land on which he built his famous 'House of Me' from a local fisherman in 1936, when Capri was a haven for Fascist grandees. After sacking his architect, Adalberto Libera, Malaparte boldly pressed on to complete the house himself in 1938, while under house arrest on Mussolini's orders. Malaparte had supported the Fascist regime and profited from the rewards it freely dispensed to its own, but he had become increasingly disillusioned as Italy drifted toward one-party-state totalitarianism. In a letter to fellow dissident Indro Montanelli, he wrote, 'The one discipline that can be asked of me is that I do not write what I think. I cannot be asked to write what I do not think.'

| The Case of Curzio Malaparte |

|

Malaparte was, like Godard, a solitary soul; a defiantly independent, complex and conflicted figure. A shameless self-publicist, like Godard, he was often accused of dilettantism by his detractors. Like Godard, his all too obvious talents were all too often hitched to a gift for sophistry. Born Kurt Erich Suckerth, his vainglorious choice of nom de plume is itself revealing: 'Bad Boy' Malaparte (the bad part) as opposed to the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (the good part). An enthusiastic early Fascist, he joined the Italian Communist Party after the liberation, seemingly in good faith, and, like Godard, subsequently drifted toward Maoism. He travelled to China to interview the Mao and left his entire estate, including Casa Malaparte, to the People's Republic of China in his will (which was successfully contested by his surviving family).

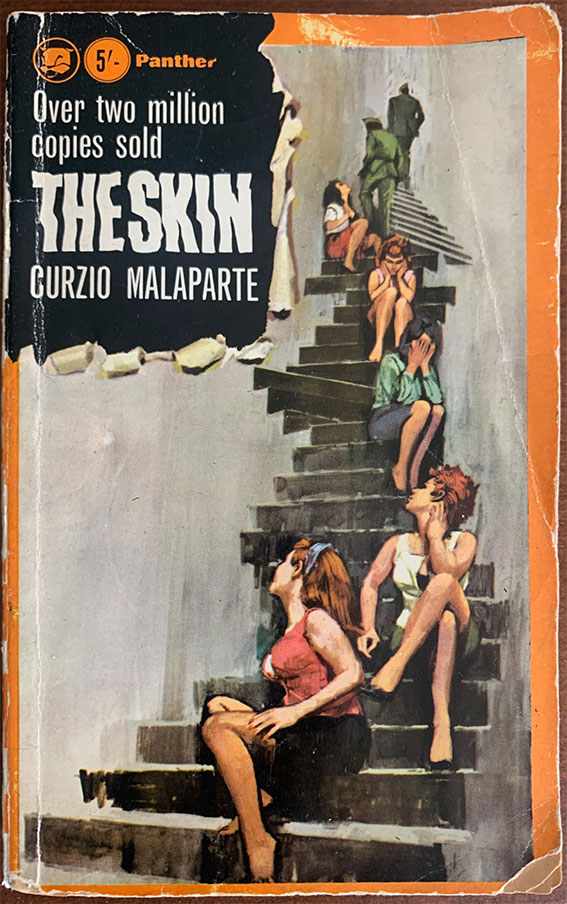

I mention Malaparte, in closing, not only because Le Mépris couldn't, in a sense, have happened without him, but also because he seems a useful test case or case study – a hook on which to hang an argument about whether we should heed repulsive, if talented individuals. That Malaparte was a homophobe, a racist and an anti-Semite is not in doubt. If we adopt a zero-tolerance approach to anti-Semitism, fascism, homophobia, misogyny and racism, must we also throw Malaparte in the dustbin (and, by implication, the films of Jean-Luc Godard). A useful starting point might be to ask if Malaparte was even talented. It would certain be easier to forgive and forget Malparte's fascism were his unreliable accounts of the barbarism of war – Kaputt and La pelle (The Skin) – not so saturated in a sublimated self-disgust that flowed, in turn, from his repressed sexuality, and which echo in his contempt for all that's noble and kind in humankind. In his preface to Malaparte's Italia babara, the staunchly anti-Fascist publisher of the book, Piero Gobetti, called him 'Fascism's best pen'. More commonly, opinion on his cultural merit divides on political lines, as tends to be the case with Godard. Trotsky called him a 'pseudo-theorist of fascism.'' Gramsci saw only an arriviste composed of 'a boundless vanity and a chameleon-like snobbery.' In both, cases the evidence for the prosecution is inconclusive, so, let's delve deeper.

When I first read Malaparte, I felt burning fury at being dragged through the cesspit of human depravity by a writer who seemed so signally devoid of human sympathy. My anger deepened when I looked further into his 'reportage'. Who could forgive a writer who invented the repulsive scene, in Kaputt, where the fascist dictator Ante Paveliċ serves up not Fortnum & Mason Oysters but 400 pounds of Serbian eyeballs? Who could forgive fabrication of the repellent scene, in La pelle, where Malaparte parleys with a cohort of crucified Jews who beg him to end their lives? Now, though, I consider his depictions of barbarism in liberated Naples a useful, if stomach-turning foil to Norman Lewis's more sociable and sanguine Naples '44. Now, I'm able recognise the value of work that can be placed in the honourable company of anti-war classics like Joseph Heller's Catch 22 and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five. Whether Malaparte's cynical depictions of war bent the truth out of shape for his own ends or deployed sly invention in the service of truth (what Gary Indiana calls 'lies that show us the truth') now seems beside the point.

Was Malaparte a visionary light years ahead of his times when he highlighted the brutalisation of women in war or a salacious misogynist profiting from pornographic sensationalism? Does it matter whether his uncharacteristically credulous acceptance of Mao's cult of the personality flow naturally from his fascism? And what to make of Malaparte's homoerotic hero-worshipping of the 'innocent' invading Americans, with their spick n span uniforms and visceral dislike of the far neater British? Perhaps it's best not to either puzzle too much or linger too long over prejudices as various and virulent as those excreted by Malaparte. Isn't the work the thing and, anyway, who are we to judge – never having witnessed Operation Barbarossa or the liberation of Naples? In the preface to English edition to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattar's Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia Michel Foucault said, 'The strategic adversary is fascism . . . the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behaviour, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us.'

I began this review by sidestepping the debate about the treatment of women in Le Mépris, I obviously sidestepped it again by turning the spotlight on Malaparte, and now I shall sidestep it once again by concluding with a thought about lists. Many, even among those of us whose thoughts on lists find echo in Elena Gorfinkel's (see Another Gaze), whooped with startled delighted when Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce came from nowhere to top Sight and Sound's Greatest Films of All Time list. The #MeToo movement has shifted the cultural conversation to such a degree that even those in Gorfinkel's corner now consider the Sight & Sound poll an essential corrective, an invaluable cinematic seismograph channelling our shared anxieties about vital intersectional questions of representation – concerning gender and race, class and unacknowledged territories, about neglect of significant eras and movements in film history, and about the film genres and forms.

It was a relief, nonetheless, that Godard remained heavily represented in that list of 'the greatest.' There are many reasons why Godard should make the cut, but not least among them is that Chantel Ackerman's quest to become a film-maker was set in motion by seeing Pierrot le fou while Claire Dennis's Beau Travail, which entered the charts at No 7, features Michel Subor – who made his name in Le Petit Soldat. We should honour the giants on whose shoulders we now stand, whether in lists or not. As Youssef Ishaghpour suggests in Cinema: The Archeology of Film and Memory of a Century, we should do so, 'Fully aware that at a time when utopian possibilities are giving way increasingly to horror, when the adman's image-information-merchandise lays claim to creative virtues, to turn away at such a moment from the absolute of art, 'beauty as promise,' would be, as Adorno said, to form an allegiance with barbarism.'

Le Mépris is being released in the UK on Blu-ray, DVD and UHD with a new 4K restoration by Studiocanal with the support of the CNC. To quote the press release:

The image was scanned and restored in 4K at the HIVENTY laboratory. In order to optimize the 4K restoration, the original 35mm negative and the interpositive were used, as well as the reference print re-worked in 2002 by Mr. Raoul Coutard, Director of Photography on Le Mépris. The restoration took 220 hours, allowing to compensate for the defects linked to the wear of time, such as deviations in colours and lighting.

I'd be keen to see just how good it looks on the UHD, given how impressive the transfer is on the Blu-ray edition under review here. Easily besting the previous Studiocanal DVD (which was no slouch for its day), the transfer here is close to sublime. It helps that key exterior scenes were shot in bright Italian sunlight on Technicolor stock, as these scenes really do pop from the screen, with perfectly balanced contrast, crisply defined detail, and gloriously vivid colour. Even the more sedately lit and graded interior scenes are clearly rendered. Minor faults visible on previous DVD and Blu-ray incarnations appear to have all been corrected, with the image remaining stable in frame and no trace of any former wear or damage.

The three available soundtracks are all DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 mono. Le Mepris is technically a multilingual film, as while French is the primary spoken language, Jack Palance speaks only in English and Fritz Lang delivers his lines in French or English, depending on who he is talking to, occasionally also speaking in his native German. On the German language track, all voices appear to be dubbed in German except for Palance, who continues to speak English. On the English language track, all of the voices except Palance are redubbed into English, and as such things go, this is not that bad, with those dubbing the French lead actors all adopting pleasingly subtle French accents, making me suspect that this was handled by the original French distributor. Sonically, the original soundtrack is definitely the best, with clear reproduction of dialogue and Georges Delerue's gorgeous score. There is no trace of any former wear and no hint of any background hiss or fluff.

Optional English, French and German subtitles are all avaiable. The English subtitles translate the French and German dialogue only, and the German subtitles pause when Lang speaks in German, whereas the French subtitles reproduce all of the dialogue. On the French and German subtitle tracks, colours are used to differentiate the languages when French and English are being spoken in the same scene (useful for those with a hearing impairement), and the French subtitles are often positioned in frame beneath the person who is delivering the line, enabling you to easily identify who is speaking in wider shots with multiple characters.

Il était une fois . . . Le Mépris (Once Upon a Time . . . Contempt) – Antoine de Gaudemar (52:28) – standard definition

Antoine de Gaudemar's 2009 documentary was commissioned as part of Marie Genin and Serge July's extensive series Un Film & son époque – a journey through film history from Jacques Tati's Mon Oncle and Rossellini's Roma città aperta through to Ruben Östlund's The Square and Andrey Zvyaginstev's Loveless. The format throughout the series is conventional enough: a contextualizing voiceover, to-camera interviews with, still images, and clips from the films. Here we hear from Alain Bergala, Charles Bitsch Michel Piccoli and others but, more importantly, from Godard himself. He is interviewed, presumably at home in Rolle, as he approaches 80, while puffing on a cigar and re-watching Le Mépris. Time hasn't softened his acerbic bite, but he is charmingly boyish, if often disingenuous as he revisits the film with mischief or sadness in his eyes.

The voiceover sets the film in the context of the collapse of the studio system, the rise of the affluent society, and reminds us that the New Wave barely lasted five years – during which time 97 directors made first features that all too often flopped. Godard says, 'We were the only film-makers who were born in the cinéma and the Cinémathèque.' He also helpfully reveals the importance of Moravia's source novel as a foundation for the project. George de Beauregard, rattled by the box office failure of Une femme es tune femme, secured the rights and Godard told him: 'I'm ready to make classical films. I love all forms, so why not?' Asked if he regretted the infamous prologue and other nude scenes, he says simply. 'No, you can't regret it. You can say it's bad but you can't regret it.'

Antoine de Gaudemar draws extensively on another documentary from another excellent French series on cinema: André Labarthes' 1967 film Le Dinosaure et le bébé from the 'Cinéastes de notre temps' series. The film (which graces the Extras in my beautifully packed two-volume Studiocanal Godard box set) contains a scintillating conversation between Fritz Lang and Godard. The touching mutual respect between the elder statesman and the young pretender is evident throughout their exchange as they discuss how they make films and debate the position of the artist in society. Godard more than holds his ground as he picks Lang's brains and even politely picks apart Lang's arguments.

Gaudemar also makes good use of clips from Le Parti des choses – Jacques Rozier's film on the filming of Le Mépris – which features, here, in the expertly curated Extras that accompany Studiocanal's extensive and engaging package of five films. He graciously acknowledges Rozier's undervalued Adieu Philippine as one of the most admired films of all New Wave films and reminds us that Rozier was no mere Godard acolyte.

While the voiceover reminds us of the liberating impact of Bardot's one-woman assault on her staid, sexually repressed times, Alain Bergala breathlessly recalls of the equally explosive and transformative impact of Godard's early films on the young. Put those two – the 'sex kitten' and the 'poet of youth' together – and sparks flew he says: 'It was a thunderbolt. Jean-Luc Godard – symbol of the New Wave. Bardot – symbol of the classical cinéma du qualité.' The film points out that Le Mépris was the seventh most watched film in France in 1963, a big success for Godard but something of a disappointment for Bardot. Perhaps the film's most astute observation, though, concerns the paradoxical love-hate relationship between Godard's generation and the U.S.A. On the one hand jazz, rock n roll, pop n pop art: on the other burning Buddhist priests and burning babies in Vietnam. Godard concludes the film by commenting, as it were from the grave, on our current realities: 'We've been stripped of our intellectual resources [but] we have technical and financial resources. You can make a film with 10 dollars. If you have 10 dollars.'

Introduction by Colin McCabe (5:31)

I mentioned McCabe's fatuous claims for Le Mépris at the start of this piece and it is beholden upon me to offer a corrective. McCabe is a charming individual and gifted academic who has made a significant contribution to our understanding of Godard, not least through the insights contained in his Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70 and his work with Laura Mulvey on the London Consortium collection mentioned above. He also helped bring three of Godard's film (Soft and Hard, Je vous salue, Marie, The Old Place). McCabe's perceptive introductions also appear before each of the films featured in the above-mentioned Studiocanal box set. I'll let McCabe speak for himself.

Paparazzi – Jacques Rozier (22:28)

This compelling documentary short was shot, with Godard's full approval, at the same time as Rozier's equally fascinating Le Parti des choses (and Le Mépris). Co-written with Michel Piccoli, it focuses on the contemporary cult of Bardot ('bardolâtrie') and the lengths the paparazzi were prepared to go to secure clandestine photographs of the most photographed woman of the era. The film details the mutually beneficial, mutually demeaning cat and mouse game played by both sides while these films was being made. It contains interviews with both the hunters and the hunted. It is lifted to another level by a wonderful and deftly edited Godardian mash-up mix of Bardot stills that echo Colin McCabe's introductory observation that the only celebrity figure Bardot might productively be compared to would be Diana Spencer.

Le Parti des choses – Jacques Rozier (10:32)

Another Rozier short, this film also takes us behind the scenes of Le Mépris and covers similar ground. We are treated to a bird's eye view of crew members racing the surf in their rush to rescue equipment left stranded on a shingle beach by the incoming tide. The interviews with Bardot and Godard are revealing and riviting. This film also emphasises the daunting inaccessibility of Capri's eastern seaboard and Casa Malaparte, which its creator called 'a claw flung into the sea'.

Original Trailer (2:31) – standard definition

Trailers are the disappointing flotsam and jetsom of disc Extras. Not so with Godard. Both precis and present, this sassy trailer blazes with colour and light, quivers with tongue-in-cheek quips, thrums with irreverent wit. A film should be made from Godard's trailers. They're compacted mini-cine-poems, ciné-hiakus that shout out: Everything is Cinema! 'The Woman – The Man – Italy – The Cinema – The Alpha Romeo – Music – The Greek Statues – The Revolver – Tenderness – Vengeance – Caresses – The Slap – The Bedroom – The Kiss – The Bathroom – The Madman – The Starlet – The Old Man – The Sea - The Steps – The Stroll – The Book – The Boat – The Quarrels – The Sun – Betrayal – Death – Love – Darkness – Misunderstandings – Love – Darkness – Death.' It's a new traditional film by Jean-Luc Godard. Don't miss it!

<< PART 1

|