| an appreciation of The Night of the Hunter, by Camus |

|

| |

"You know, all these people today want to know Mitchum was a wonderful guy. Bob was awful. He'd be drunk. He'd urinate on the set. I had to hire a policeman to go by his house in the morning to make sure he was up and ready to go to work. I don't know what Mitchum's range was as an actor. I consider him a lucky man. He played himself and was very effective in the part." |

| |

|

There are movie monstrosities, crazed, cruel and destined for a dark, corrupt and immoral immortality. Insert agent joke here. There are creatures dishing out the vilest punishments thrown on to the pure white screen only to defile it. Aliens pierce craniums and monsters devour the unsuspecting as do the wickedest sociopaths with fava beans and a flinty little red. But there is a mostly unsung movie monster that scrabbles for a place among the worst of them; a human being so corrupted by his own desires that murder is just another counter on the board game that is his life; men, women, children… If they stand in his way, they're not standing for much longer. And bad boy Robert Mitchum was playing himself? Jesus. This isn't a million miles from Dennis Hopper calling David Lynch demanding that he was the psychotic Frank in Blue Velvet. This odd coincidence aside, Mitchum is horrifically mesmeric in the role of a southern preacher (not sure if the movie shows that he really has been ordained as a man of God - jury's still out on that one). He is determined to find the ten grand his cellmate admitted was stashed back at his home. Ben Harper, played by Peter Graves (he of the original Mission Impossible TV series fame and the pilot in Airplane who asks a child "Have you ever seen a grown man naked?") plays the father who murders during a bank robbery. You get the sense that he is remorseful but desperate, trying to give his family some financial security. He pays the ultimate price at the end of a rope. But that ten grand is somewhere back at his house and after serving thirty days on a car theft misdemeanour, the decidedly un-revered Reverend Harry Powell sets off to Ohio and the dust bowl that was the mid-west in the 1930s.

One of the Preacher's most heinous traits is, of all things, laziness. He makes no real effort to conceal his obscene deceits. He appears as a man of God, a man of perceived goodness who is all too aware of the frightening and cavernous gullibility of god-fearing mid-west folk and is so accepted that he sometimes doesn't even seem to try to play the part convincingly. His fake upset at the apparent loss of his runaway wife is hard to read. Is he (in character) just a bad actor as a Preacher content to let his status fill in the emotional blanks or does he have so much contempt for ordinary folk that he allows them the chance to call him out on his deceptions? They never do. He gets everyone to fall for his lies and treachery - except one whom we'll get to in a minute. To some credulous idiots (almost the rest of the cast), you only have to wear a dog collar and ye are judged to be good. Boy, things have changed. Steeped in the holy cloth for selfish gain posing as a vessel through which the Lord's work is done, is a man who can barely be counted as a container of the tiniest drop of humanity. Mitchum is a big man, a significant presence and when he's holding a switchblade, be somewhere else. Famously for dramatic effect the Reverend sports tattoos on his fisted outer fingers, one says 'love', the other 'hate'. In a theatrical display to prove his virtue, he wrestles one hand into submission. This is the 50s equivalent of Heath Ledger's Joker from The Dark Knight asking "You wanna know how I got these scars?" And people buy this absurd pantomime because they've been conditioned (especially during the 30s in the US) to believe in the sanctity of holy men. It is precisely that oleaginous, feigned sanctity that he offers to others as proof of his virtue and if there are any questions to be asked about his actions, the same old, tired canard is trotted out – a catch all for disbelievers to look up in despair at the stupidity of mankind… "God moves in mysterious ways, his wonders to perform." And that cliché is not even in the Bible! It's the start of the first verse of a hymn written by William Cowper, a depressive who believed that the London fog (i.e. God) stopped him from committing suicide. Uh… OK. It is amazing that the creator of the universe finds time for a one on one intervention. Apologies, I forgot he was omnipresent.

If religion can ever claim to be a force for good, it is expressed in the character of Rachel Cooper played by the female star of Birth of a Nation, the radiant at any age, Lillian Gish. She takes the runaway children in and, Bible quoting as she goes about her business, indoctrinates her charges with the Lord and all his surreal and nasty ways (apologies, this was supposed to be giving Christianity some slack). She has a good heart but more importantly, she places herself in between the Preacher and the children as if it were perfectly normal for a stranger to do so. She's the only character aside from the hunted boy John (Billy Chapin) who can see what Mitchum is up to right in the middle of his hand-twisting act. Her rallying cry exposing the monster is this movie's "Get away from her, you bitch!" moment but somehow it's a little more satisfying coming from a seemingly vulnerable sixty-two year old lady.

I cannot say if people in this period of American history were really this attached to the big guy upstairs. Judging from similar movies or rather movies set in similar times (there is nothing remotely comparable to The Night of the Hunter, I can assure you), it was an easier choice to make between religion and intelligent reason in order to accept any meaning in the bitter hardships. I'm thinking Bogdanovich's Paper Moon (in which the hero sells Bibles or looking at it from another perspective, the heroine's father sells Bibles) and another Bible salesman played by John Goodman who makes short work of our convict protagonists in the Coen Brothers' O Brother Where Art Thou. Where there's a hell on Earth, there's some bastard conning the populace with the heavenly invites. But Mitchum is not just a con man. He's homicidally dangerous, manipulative and prepared to go the distance. He marries the grieving widow to stay close to the money (a vulnerable, downtrodden and perfectly pitched performance from the great Shelley Winters) and one of the two young children sworn to secrecy by their father, John, immediately sees through that bastard's façade. His sister is too young (Sally Jane Bruce as Pearl) and often falls for the edgy charms of a man used to getting what he wants by any means. But the children are resourceful and force him to hunt them down.

One aspect of Mitchum's character that I first thought odd was his dismissal of men's lust as a thing of evil and subsequent shunning of his new wife on their wedding night. This was subtly worked against the woman he claims left him one night without saying a word. If sex is not a desire in this man, I wondered chillingly what replaces it. I won't say what happens but let's just acknowledge the haunting images directed by Laughton but photographed by one of Orson Welles' cinematographers, Stanley Cortez. I won't wax too lyrical about the influences on the stunning black and white photography because that's someone else's turf; coming soon to a page you're already on. As a child when I first saw this film, I remembered three images that I was happily able to fit together into the whole after a recent reviewing. One, I'd like to keep as a surprise but hey; you will know it when you see it. Another was the procession of the boat down the river with subtle variations in framing and foreground (those rabbits, right on cue) and the third is the children running upstairs from a cellar and Mitchum's hands outstretched almost Nosferatu-like, grasping at them while they are just out of reach. I can still recall the overtly unrealistic feel of the movement but even then I believed that was the point. Here was another boogeyman, fortunately one who obeys basic laws of physics. You know who you are, Michael Myers.

The Night of the Hunter was judged a culturally significant film as hailed by the Library of Congress and now sits protected in a vault somewhere, a piece of living history. It's also a damn fine thriller with an irredeemable movie monster too often overlooked by populist polls. If you like your serial killers theatrical but utterly without conscience, then roll up for Preacher Harry Powell…

| an appreciation of the film's visual style, by Slarek |

|

When you hit your second year at film school, or at least the one I attended, you were finally able to stop piddling around with stills photography and focus exclusively on film and TV production. You were expected to try everything but were encouraged to choose a specialism to focus on in the third year. Most went for directing (don't tell me you're surprised), one chose sound recording (an astute move, as it turned out, as he was constantly in demand) and three of us elected to specialise in cinematography. I can't remember exactly when I decided that camerawork was definitely for me, but I do recall two of the films that first sold me on the notion of cinematography as a stand-alone art form. One was the 1970 The Conformist, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and photographed by Vittorio Storaro, the other was The Night of the Hunter, photographed by Stanley Cortez and the only film directed by actor Charles Laughton. Don't get me wrong, it wasn't that I didn't appreciate the excellent work of the many other cinematographers whose films I was by then keenly studying, it's just that something about the look of these two particular movies left me absolutely reeling. My views on The Conformist are perhaps best left for a later review, but since we're talking about The Night of the Hunter...

When I first laid eyes on Laughton's extraordinary film I'd never seen anything like it. The thing is, over thirty years and several thousand films later, I've still never seen anything like it. It seems astonishing in retrospect that a film that is now ranked as one of the all-time cinema greats took a critical pounding on its original release and was a box-office flop. Laughton, as a result, never directed another film, something I've always believed was a tragic loss to cinema, but ironically adds to the film's unique tone and look.

Stanley Cortez photographed over eighty films during his distinguished career, a fair few of which – The Magnificent Ambersons for Orson Welles, The Secret Beyond the Door for Fritz Lang, The Three Faces of Eve for Nunnally Johnson, and Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss for Samuel Fuller among them – have gone on to achieve cult classic status (he also shot the 1957 They Saved Hitler's Brain, which has attracted an altogether different cult following). But his work on The Night of the Hunter really is unique, a blend of purposefully framed conventional shots (reverse coverage for conversations, close-ups for emphasis), suggestive camera moves, alternately naturalistic and high contrast expressionist lighting, and imagery whose poetry and compositional beauty is frequently breathtaking.

But hang on a minute. Something I did not appreciate back in my college days was that these shots are not just about choosing the right angle, inventively positioning the lights and framing the subject in an attractive or narratively telling manner. Coming back to the film some years later I became very aware of one thing: these images were not photographed, they were meticulously and expertly constructed through a collaboration between Laughton, Cortez, art director Hilyard Brown and special photographic effects supervisors Louis De Witt and Jack Rabin.

Nowhere is this more striking than in the river trip undertaken by the two fleeing children, a fairy tale journey realised as a series of exquisite storybook images that serve to heighten the children's innocence, isolation and potential vulnerability. And while cleanly compositing imagery is now something that any creative teen can do in their bedroom with a laptop and the right software, back in 1957 the planning and work required to construct such shots – ones that would occupy just a few seconds of screen time – almost beggars belief. Thus if Laughton required the boat to come to shore close to a silhouetted barn at sunset, then the fascia of barn and the neighbouring house had to be constructed and the skyline filtered around it, quite possibly in-camera. And if he required a deep focus shot that placed two rabbits in the foreground as the boat passed behind them, the elements had to be filmed separately and the rabbits (actually the same one photographed from two different angles) carefully composited in post production using a traditional but time-consuming photochemical technique, one that I've rarely seen employed as convincingly as it is here.

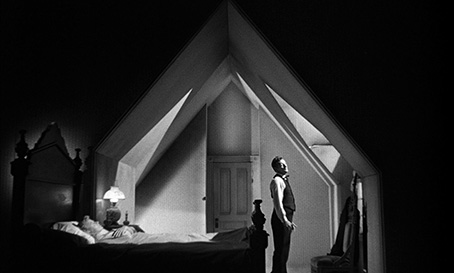

Yet none of this visual boldness and experimentation feels purely ornamental, with every shot serving either the narrative or character and frequently both. Thus while visually arresting, the aerial wide shot that provides with our first glimpse of a travelling Powell also connects perfectly with the rise up from the location in which his previous victim has just been discovered and provides a God's eye view that ties in with the one-sided conversation that follows, as Harry questions the Almighty about who he should kill next. Catholic imagery abounds, appropriate for a film warning of the dangers of false prophets, and peaks in the extraordinary wide shot in which Harry prepares to commit the murder that launches the film's second act, and the attic room in which this heinous crime is to take place takes on the look and feel of a small-town church, the implication being that Harry is not just killing for money, but really does believe he is doing the work of God.

But perhaps the most startling image of all, one that haunted me in my youth and still astonishes today, is all the more jarring for being one that earlier scenes and even the film's year of production have seemingly assured us that we would not see. Women are being murdered, but this is 1957 and we are thus not shown the crimes or their grisly results. A pair of immobile legs lying awkwardly in a place they should not be is all we need to conclude that we're actually looking at a corpse, and the religiously overtoned killing discussed briefly above fades out just before the act itself is shown. Yet when the body of the victim of this pivotal murder is found, tied in the passenger seat of her car at the bottom of a lake, the waving of her hair in the water echoed by the surrounding weeds, it is not just shown but dwelt on, lit and arranged in frame like a terrifyingly beautiful work of surrealist art.

The bad news for this new UK Blu-ray from Arrow Academy is that the film is already available on Blu-ray in the US as part of the Criterion Collection, and that disc features a new digital transfer made from 35mm film elements restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive in cooperation with MGM Studios. Beat that, Arrow. Well the good news is that the exact same restoration has been used for the transfer here. Not having immediate access to the Criterion release, I'm not in a position to directly compare the two, but on its own merits the Arrow transfer is pretty damned impressive. As with the Criterion transfer, the image here is framed 1.66:1, which is generally considered to a more accurate projection ratio than the 1.37:1 image of previous DVD releases. The contrast is punchy and those all-important black levels are as dark as pitch, but the tonal range in brighter scenes is very pleasing. I'm not going to claim that the image here is as sharp as some other restorations of past classics that have appeared on Blu-ray in recent years, but it still knocks the spots off previous DVD editions, though it's worth noting that the film grain is also more pronounced here. There's precious little trace of dust or damage, though there is some brightness flickering on a few of the wider shots – the morning sky at 1:07:25 is a particular offender here and one of the few shots with any visibly remaining damage. On the whole, though, an impressive upgrade.

The original mono soundtrack has been cleanly reproduced on a Linear PCM 2.0 track, as opposed to the 1.0 track on the Criterion disc. No evidence of damage or distortion is evident.

Somewhat surprisingly, there is also a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround remix. I'm never that keen on tinkering with how films originally played, and while for the most part the surround work is confined to music and effects, the sometimes pronounced use of separate channels is occasionally a little jarring. A prime example occurs when Powell first shows up at Rachel Cooper's door and offers to tell her the story of right hand/left hand. On the mono track, there is no change in audio quality as the camera switches from Powell to Rachel Cooper, but on the surround track the slight abruptness of the sound edit before the word "left" (this has always been there, likely the result of melding the soundtrack of two takes together) is painfully emphasised when the sound of Powell's voice switches from the centre to the front right speaker on this very word, a jump made worse by what appears to be a small but noticeable tonal shift. Elsewhere the mix is more subtly handled and the music actually feels a little richer here, but personally I'd stick with the original.

But there's more. A music and effects track has been included (there have been a few of these recently), on which both elements play at a lower volume than they do on the mono track. Trainee Foley artists will doubtless have a ball.

English subtitles for the hearing impaired have also been included.

Once again comparisons with the Criterion release deliver a mixture of good and not-so-good news. The good news is very good, that three of the extra features from the Criterion disc – including the best one – have also been included on the Arrow release. The not-so-good news is that the other seven features on the Criterion disc have not. So let's get to it.

Charles Laughton Directs 'The Night of the Hunter' (159:30)

A marvellous special feature that takes us chronologically through the film using the original rushes, complete with Laughton's off-camera directions to the actors, alternative takes and angles, the odd out-take and blooper (Peter Graves actually smacks Robert Mitchum in the mouth when he leans over the bunk in their prison cell scene), and even footage of actor Emmett Lynn playing the role of Uncle Birdie before Laughton replaced him with James Gleason (the reasons for the change are provided). Long it may be, but for cinephiles this plays like a detailed and enthralling Charles Laughton masterclass on directing actors for film. Much of it plays without commentary, but project supervisor and narrator Robert Gitt is on hand to contextualise the material, provide biographical and technical information, explain how effects were achieved, and provide a useful epilogue that covers the film's release, its box-office and critical failure, and what the actors went on to do next. At one point he also invites us to speculate whether Laughton's seeming hostility towards Shelley Winters in one scene was the product of genuine frustration or a directorial trick used to prompt a particular reaction from her. And as directorial tricks go, Laughton has a beauty for prompting young Billy Chapin to clutch his gut at the emotional pain of seeing his father clobbered by the police – just before the take, he slaps him in the stomach. It's worth noting that all of the footage here appears also to have been carefully restored, and for the most part looks splendid.

Stanley Cortez Interview (12:55)

An interview with cinematographer Stanley Cortez, conducted in English but subtitled in French, which although only 13 minutes in length is a small treasure trove of information. Cortez talks about working with Laughton and what they learned from each other, why he changes his concepts for lighting and camera technique when he hears the dialogue delivered by the actors, and how music informed his lighting of one scene, which in turn changed how the scene was subsequently scored.

Trailer (1:38)

Not the most thrillingly packaged sell in the world, particularly given the material at the trailer makers' disposal. This is not an easy extra to find on the review disc, as selecting it from the extras menu plays the Charles Laughton Directs documentary instead – the trailer, it turns out, is hiding at the tail end of this (the listed running time of the documentary has been adjusted to take this into account). Hopefully this has been sorted for the release disc.

Booklet

Note: coverage of this extra feature was added after the initial review was posted, as it was not provided with the review disc. Our thanks (once again!) to disc and booklet co-producer Michael Brooke for providing us with a copy

OK, while the Arrow disc may have kept pace the Criterion one on the transfer and three of the extra features, here it really goes out on its own, and as accompanying booklets go, this one is right up there with top flight Masters of Cinema and BFI releases. The contents are frankly superb and compliment the film handsomely. Following a textual reproduction of Harry Powell's famed "right hand/left hand" speech, there is a comprehensive essay on the making and eventual release of the film by respected cinema writer and arts documentary maker David Thompson, extracts from a number of contemporary reviews from the US and UK press (most of which are depressingly dismissive), Gavin Lambert's altogether more insightful review from the Winter 1955/56 edition of Sight & Sound, a wonderfully detailed essay on the contribution of screenwriter and critic James Agee by F.X Feeney (also a respected critic and screenwriter), notes on the projected aspect ratio, credits for the film, high quality stills a reproductions of international posters. It also looks lovely. Superb.

This is a tricky one. The Criterion 2-disc Blu-ray definitely has the edge here in the number and range of its extra features, but if you're based in the UK then you'll need a multi-region player to play it and it will cost you almost twice as much as the Arrow Academy disc. I'm not in a position to be able to directly compare the two transfers (yet), but the Arrow transfer has been sourced from the same restoration as the Criterion Blu-ray and thus should look identical, it includes the best extra feature and two others from the Criterion release, and is accompanied by a superb booklet, all produced at what was doubtless a fraction of the budget Criterion had to work with. Frankly, if you can't stretch to the cost of importing the Criterion disc or don't have a multiregion player, you won't feel cheated. |