|

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

That’s one of the most famous opening sentences in twentieth-century English literature. Just see how much exposition it conveys in a few words, with that final word immediately telling us that we are not in the world we know, but another one. And this television version of that novel, controversial in its day, remains one of its finest adaptations. By the way, the novel title is Nineteen Eighty-Four (words rather than digits) and that’s something this landmark television production from 1954 respects.

While opinions vary if Nineteen Eighty-Four is the best of the six novels that George Orwell published, it’s undoubted that, along with Animal Farm (strictly speaking a novella rather than a novel) it’s the one that is most often read. Both have been taught in schools (I studied both in my time), and has been the most influential. Along with Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, published in 1932, it’s a key work of dystopian science fiction. It’s clearly a work of SF, influenced by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We and very much influencing in its turn other work in the genre, even if it was never published as a genre novel. Along with Huxley’s novel, and those of John Wyndham a little later, it’s a SF novel that reached a wider mainstream audience. Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn’t a work of prophecy, but an extrapolation from Orwell's present. It has lost none of its relevance and several of its concepts have entered the language: Big Brother, Room 101, Newspeak, and so on.

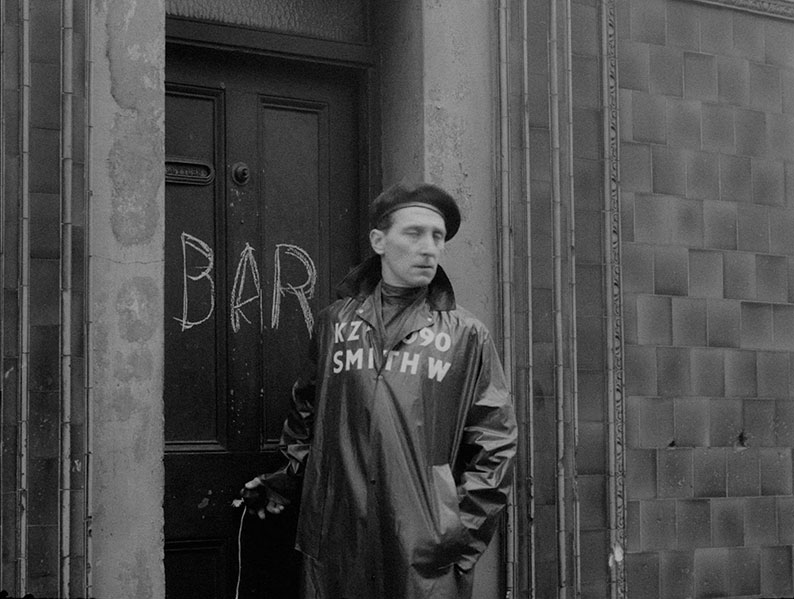

Britain, or Airstrip One, is part of a superpower called Oceania ruled by Big Brother. Posters of his implacable face are on every wall, with the slogan BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU. In each house, a telescreen broadcasts (fake) news and propaganda and also to monitor the inhabitants. Winston Smith (Peter Cushing) works at the Ministry of Truth, rewriting the news to remove references to “unpersons”. The official language is Newspeak, a more and more telegraphic form of communication, with the goal of reducing the available words as a form of populations control. Eventually, those inclined to rebel will have fewer and fewer words to think their rebellious thoughts. Winston meets Julia (Yvonne Mitchell), a member of the Anti-Sex League, and they fall in love.

That’s as far as I’ll go regarding a plot summary. While the plot of the novel is well known, be aware that there will be plot spoilers in the remainder of this review.

Orwell might have called his final novel The Last Man in Europe or maybe even Nineteen Forty-Eight. But Nineteen Eighty-Four it was, so named by reversing the digits in the year the novel was written. By then Orwell was severely ill from tuberculosis. The novel was published in 1949 and Orwell died on 21 January 1950, aged just forty-six. The interest in the novel was immediate and its first adaptation was in the year of publication, on NBC radio in the USA: an hour-long version on 27 August, with David Niven playing Winston Smith. Also in the USA, CBS broadcast an adaptation, also an hour long, on 21 September 1953, with Eddie Albert in the lead. In Britain, the BBC, then the only television broadcaster, had been interested in producing their own version, and they did so on 12 December 1954, in the thirtieth pre-anniversary of its title year.

Thomas Nigel Kneale was known as Tom to his family and friends but used his middle name professionally. He was born in 1922 and raised on the Isle of Man. At first Kneale worked in a lawyer’s office, but left the profession. Not accepted for War service, he turned to writing and, for a while, acting, moving to London and enrolling at RADA. A short-story collection, Tomato Cain and Other Stories, was published in 1949, which impressed Elizabeth Bowen so much that she wrote a foreword to it. The book won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1950, after which Kneale abandoned acting and turned to writing full-time. He clearly saw the potential of television, which had restarted in the UK in 1946 after being closed down during the War. In 1951, BBC Television took him on as a staff writer. At the time, most television drama was adapted from other media, particularly the stage. Drama was broadcast live and repeats were, as in the theatre, brought about by reassembling the cast and crew for a second performance. Kneale was prolific, writing anything that came his way. An early credit was the 1952 play Arrow to the Heart, for which he contributed additional dialogue. There, he met the play’s writer and director (billed as “producer”, theatre-style, then), Austrian-born Rudolph Cartier. Television drama then was broadcast live, and repeats reassembled the cast and crew for a second performance. Both men thought that television drama of the day was too theatrical and aimed to do more with the medium, making it something distinct from the stage, nor it being radio with pictures. By so doing, they pushed at the technological limitations of the time.

Their first example of this was The Quatermass Experiment. In the summer of 1953, the BBC had a gap in their schedule, in fact due to a proposed adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four falling through. This was because the script, by Hugh Falkus and Orwell’s widow Sonia Brownell, was not considered up to scratch. So Kneale and Cartier came up with a science fiction serial broadcast in six weekly episodes between 18 July and 25 August 1953. As more people had access to televisions then, largely due to the coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation a month earlier, the serial was a considerable success. Cartier and Kneale's next collaboration was an adaptation of Wuthering Heights, broadcast on 6 December 1953 and repeated four days later). That had been instigated by the actor Richard Todd, who played Heathcliff. Cathy was played by Yvonne Mitchell, who would work again with Cartier and Kneale in their next production, which they started work on in January 1954.

Kneale's adaptation streamlines the novel: like all versions I've seen, it removes the forty-odd pages of political textbook from the middle. Even so, Orwell's visual style does lend itself to screen adaptation. He was an advocate of “transparent” prose (like a window pane, as he famously once said) that doesn’t draw attention to itself but enables us to “see” what is being described with as much clarity as possible. It's a story that’s hard to wreck. I haven’t seen the 1956 cinema version but that certainly tried by giving the story a happy ending. (The same applies to Halas and Batchelor's 1954 otherwise admirable animated feature of Animal Farm. Maybe the makers of these films were conscious of the Production Code then in force in the American cinema industry.) Peter Cushing at this time hadn’t worked for Hammer in the roles which made him famous. He was forty and had built up his career via character parts to leads like this, gives a fine performance, matched by Yvonne Mitchell and, as the villain of the piece, O' Brien, André Morell, who would play the Professor in Kneale and Cartier's 1958/59 serial Quatermass and the Pit.

Even though television drama was predominantly live, via 405-line cameras from the studio to whichever parts of the nation had television transmitters then, some material was prefilmed, usually on black and white 35mm film, in studios (Ealing, for example) or location material. This was played in during the broadcast. Some scenes were prefilmed for logistic reasons, to give the cast and crew time to be in position for the next live-broadcast scene. For example, the Room 101 scene is largely played in close-ups of André Morell, and the scene where O’Brien shows a now-broken Winston his image in a mirror was prefilmed, to allow time for Peter Cushing to be made up for the final scene, where he and the similarly-broken Julia meet again in a cafe. Other material was prefilmed for reasons of complexity, such as the Two Minute Hate scene near the start. Some shots of telescreens were prefilmed because the budget did not stretch to having one in every set. Other prefilmed material involved special effects, here the work of Jack Kine and Bernard Wilkie. Music was often played in via gramophone records during transmission, but in this case, John Hotchkis’s score was played by a seventeen-piece orchestra in the next-door studio.

However, the majority of the play was performed and broadcast live, on the evening of 12 December 1954. That was, as usual for a new BBC drama at the time, a Sunday, and many of the complaints – which started soon after the broadcast began – said that such adult material was out of place on a Sunday, especially a Sunday in the run-up to Christmas. There were complaints about the content and a woman was reported to have died while watching. (She had had a heart attack but the play’s content was not to blame.) Questions were asked in Parliament and five MPs signed a motion deploring the BBC's tendency, especially in its Sunday evening dramas, “to pander to sexual and sadistic tastes”. (In fact, the previous weekend’s play, Young Renny, had had complaints due to sexual references and a postcoital scene had been removed from the Thursday repeat.) There were calls for the scheduled repeat on Thursday 16 December to be cancelled, but the BBC Board of Governors early on decided that it would go ahead, and so it did. The then BBC head of drama, Michael Barry, introduces the drama on-screen (included in this transfer) amplifying the warning that had gone out before the first broadcast. He also, charmingly, apologised to the citizens of Aberdeen, whose television transmitter would have gone live in midweek had it not been for a power failure. So Aberdonians’ first experience of television drama was rather more adult than they might have anticipated.

One way in which Cartier was ahead of his time was in the use of telerecording, which at the time involved a 35mm camera being synchronised to a television monitor and the output of the 405-line video cameras (377 lines of actual picture) being captured on film. While it's true that the majority of early television, especially from before the War, was beamed out live and never recorded and no longer exists, that isn't entirely so: early broadcast material included newsreels, cartoons and occasional feature films. Telerecording was used for certain prestigious live events. The wedding of the then Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip from 1947 survives in this form, as indeed does the Queen's Coronation. However, the earliest surviving telerecording of a live play is another Cartier production starring André Morell and the original Quatermass, Reginald Tate, It Is Midnight, Dr Schweitzer, broadcast on 22 February 1953 and “repeated” on the 26th, the latter being the broadcast which was telerecorded. Other early telerecordings include the first two episodes of The Quatermass Experiment, the earliest surviving examples of episodic drama. Several people who worked on Nineteen Eighty-Four said that the first performance was the better of the two, but it is the second which was telerecorded and which survives and has been repeated, in 1977 as part of the BBC's celebrations of the fortieth anniversary of its television service, in 1994 following Cartier's death, and most recently in 2003. The most recent adaptation on the BBC was for radio in 2013, with Christopher Eccleston in the lead.

In 1965, the BBC made a new version of Nineteen Eighty-Four using a revised version of Kneale's script. This was shown only once, and was since lost, to be found again in a cache of BBC drama productions in the US Library of Congress, in a copy missing a section of some eight minutes but otherwise intact, a worthwhile version in its own right. There have been later adaptations, on radio (including another from 1965, for the BBC Home Service, with Patrick Troughton and Sylvia Syms as Winston and Julia) and stage and in 1984, a second cinema version, directed by Michael Radford and with John Hurt as Winston Smith. However, this 1954 version remains one of the best, even allowing for the technical limitations.

This version of Nineteen Eighty-Four has been announced for disc release twice before now, both releases not happening due to Orwell’s estate. However, Orwell’s copyright lapsed in the UK and EU on 1 January 2021, due to its being seventy years since the year of his death, so that is no longer an impediment to this release. (The novel is still in copyright in the USA, as under American law it remains so for ninety-five years after publication.) The BFI’s release is dual-format, with a Blu-ray and a PAL-format DVD, encoded for Regions B and 2 respectively. This review is from a Blu-ray checkdisc. The disc carries a 12 certificate.

The transfer is from a 2K scan of the 35mm telerecordings (negative and positive) and the 35mm negative of the prefilmed material. Even if you acknowledge that you are watching on larger and more unforgiving screens that would have been available in 1954, this isn’t quite what you would have seen if you were watching then. A decision has been made to maintain the resolution of the prefilmed inserts, and as you would expect from scenes originating on 35mm film, they look sharp with strong blacks and contrast spot on. This contrasts with the soft and at times blurry (on movement especially) live studio material. This isn’t a complaint as this is inherent in the source material, and it looks as good as it’s ever likely to do. The transfer includes Michael Barry’s introduction and the interval, with an orchestra playing for three minutes and twenty-six seconds starting at 59:58. The transfer is 1080i50, reflecting its television origins and its intended playing speed of twenty-five frames per second.

The soundtrack is the original mono, presented as LPCM 1.0, also restored from the original magnetic tracks. Given the time this was made, it’s inevitable that dynamic range is rather less than you would expect nowadays, but it’s clear and well balanced. There are English hard-of-hearing subtitles available, and I didn’t spot any errors in them.

Audio commentary with Jon Dear, Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray

Newly recorded for this edition, this commentary is moderated by writer and television historian Jon Dear, who introduces fellow historians Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray, the latter being Nigel Kneale’s biographer. This is an excellent commentary. Hadoke in particular has shown his worth in many past commentaries on vintage-television disc releases, in particular the BBC’s Doctor Who range, but also including the BFI’s releases of Out of this World and Out of the Unknown, but the others play their part equally as well.

Excerpt from Late Night Line-Up (23:39)

Late Night Line-Up was BBC2’s regular discussion programme, and here on 27 November 1965, the night before the channel’s new production of Nineteen Eighty-Four (also on a Sunday night), they look back at the controversy about the earlier version, eleven years earlier and at that point not having been repeated other than the original two broadcasts. The programme is presented by Nicholas Tresilian. There are plenty of quotes from the newspapers of the time, and interviews with Rudolph Cartier, Nigel Kneale, Peter Cushing, Yvonne Mitchell and André Morell. Cartier says that he suspected some reaction to the play but had underestimated the one it did receive. Kneale regarded adapting such a well-known novel as not so much a challenge as a dare.

Nigel Kneale: Into the Unknown (72:16)

Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray appear again, this time in an item recorded at HOME in Manchester on 9 January 2022. It’s captured by a fixed camera, so that images which appeared on screen to the audience aren’t visible to us – though Hadoke refers to several of them which are offscreen-right. As well as Murray being Kneale’s biographer, Hadoke has a stake in the subject, having adapted Kneale’s now-lost television play The Road for BBC Radio 4. He is also working on a book on the Quatermass serials. For just under an hour and a quarter, both men give an overview of Kneale’s life and career in more or less chronological order, and as a primer in things Kneale it serves very well.

The Ministry of Truth (23:55)

Television historian Oliver Wake is interviewed by Dick Fiddy from the BFI, in a piece intended to dispel some myths about the production and the controversy surrounding it. This takes the form of Fiddy bringing up each urban myth (or otherwise) and Wake confirming or debunking as appropriate. These include the nature of the letters of complaint (not as much negative as thought, and not all about the play’s content), whether or not someone died during the broadcast (see above), whether or not the second broadcast was likely to be pulled and whether or not Prince Philip had intervened (he was reported to have enjoyed the play, as had the Queen, Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother). The Communist newspaper The Daily Worker objected to the play on political grounds, for Orwell’s and the novel and play’s view of socialism.

Image Gallery (1:50)

A self-navigating gallery, comprising black and white production stills and a reproduction of the Programme-as-Broadcast (PasB) paperwork for the first broadcast. The original typewriting of the latter is a little faint but still quite readable.

Original Script

A 113-page gallery of the shooting script. As with the PasB paperwork, the lettering (typewritten originally) is a little faint but there shouldn’t be many issues in reading it. This is an on-disc item on the Blu-ray and a downloadable PDF on the DVD.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing only, runs to twenty-eight pages. There is a spoiler warning, as there is with my review, though the plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four is likely to be well-known. Oliver Wake begins with the overview essay, “A Timely Warning”, which begins with the success of The Quatermass Experiment causing the BBC to invite Cartier and Kneale to tackle Orwell’s novel. This developed into a big-budget production (£2500, later raised to £3000). Wake covers the production and then tackles the controversy, the first stirrings of which came from the play’s designer Barry Learoyd feeling nauseous after reading the script and Cushing and Mitchell admitting to nightmares and disturbed sleep as they rehearsed the production. Wake then describes the public reactions after the first broadcast and details how they were not just because of the torture scenes later in the play. Some commenters suggested that the people involved in the production must have been readers of horror comics, a then-current moral panic. Wake also establishes that the decision to continue with the second broadcast was made early on. An example from a few years earlier of a play having its repeat broadcast cancelled (Party Manners, broadcast 1 October 1950) had caused complaints of alleged political censorship, may have deterred the BBC from cancelling a play again. Orwell’s novel was only five years old when the play was broadcast and the BBC’s adaptation not only increased its sales but may have helped establish the reputation it still has.

David Ryan’s piece “It’s Like Nineteen Eighty-Four” looks at the play from the angle of the author of its source text and begins with the story of the only George Orwell in the London phone book receiving abusive phone calls after the play was first broadcast. Ryan then goes on to talk about Orwell (the author, not the unfortunate man who shared his name with the author’s pseudonym) and discusses the previous adaptations of Nineteen Eighty-Four, including the American ones for radio and a strange-sounding Australian radio version which brought in Vincent Price to play Winston Smith, and the later cinema, television and radio adaptations.

After full credits for the play, Oliver Wake returns with a four-page biography of Rudolph Cartier. There are also notes on the extras and on the restoration, and plenty of stills.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a key work of twentieth-century English literature, which is reflected in the number of times it has been adapted, for radio, television, stage and cinema. Even if you make allowances for its technical limitations, this 1954 BBC version remains one of the definitive adaptations of Orwell’s novel, and is well served by this BFI release.

|