|

Part 1

"Flat areas, figures that float in a vacuum, characters hovering at

various points around the frame, a weightless camera, inconsistent

figure positions, movements and glances: like no film Dreyer made

before this, as surely as any film by Eisenstein and Vertov, La

Passion de Jeanne d'Arc foregrounds perceptual contradiction." |

David Bordwell, from The Films of Carl Theodore Dreyer |

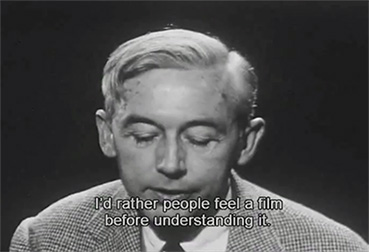

"What interests me most – and this comes before technique – is

reproducing the feelings of the characters in my films. That is, to

reproduce, as sincerely as possible, the most sincere feelings possible." |

Carl Dreyer, interviewed by Michel Delahaye,

Cahiers du cinéma, 1965 |

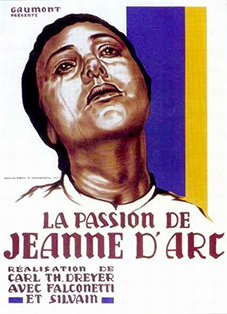

Reputations rise and fall, fall and rise, as the climate of opinion and belief changes. Joan of Arc was born in the Vosges in 1412, burnt at the stake as a heretic in Rouen in 1431, and rehabilitated in 1452. Later, in a bid to round up a restive flock increasingly drifting towards atheistic socialism, the Catholic Church declared Joan 'venerable' in 1904, beatified her in 1909, and finally canonised her in 1920. Carl Theodor Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc/The Passion of Joan of Arc has experienced similarly fluctuating fortunes. The film premiered in Copenhagen in 1928, was unpopular with audiences, eclipsed by the talkies, and initially considered 'uncinematic' by advocates of pure cinema. It was subsequently declared venerable by Godard in 1962, sanctified by Pauline Kael in 1982, and canonised by those who voted it into the top ten of Sight & Sound's 'Greatest Films Ever' polls in 1952, 1972, 1992 and 2012. The Hundred Years War is long forgotten, but the martyred Maid of Orleans and Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc remain firmly rooted in the contemporary cultural landscape. France marked the 600th Anniversary of her patron saint last year, but Marine Le Pen's Front National and François Hollande's newly elected Socialist Party government remain locked in a tug of war for public possession of the mythic symbol that is Joan. Meanwhile, The Passion of Joan of Arc is entrenched as an immutable symbol of silent cinema and Dreyer's position within the cinematic cannon seems set in stone – perhaps to the detriment of serious criticism of the film and considered enquiry into that most complex of men and his darkly beautiful work.

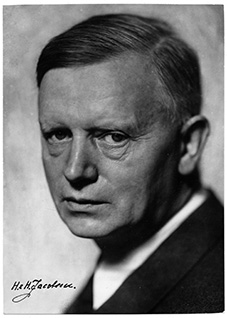

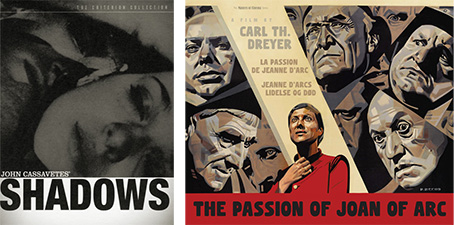

Fortunately, a range of resources is now available to those wishing to make their own minds up about Dreyer. The publication, in 1981, of David Bordwell's magisterial study, The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, was complemented, in 1982, by Maurice Drouzy's indispensable biography, Carl Th. Dreyer Né Nilsson (currently available only in Danish and French editions). Both books added enormously to our understanding of Dreyer, as did the work of the late Dale Drum and his wife, Jean. After Professor Drum died, in 1991, Jean Drum completed the book they had been working on since the 60s: My Only Great Passion: The Life and Films of Carl Th. Dreyer (2000). Additional snippets of biographical information have filtered out subsquently. The most significant breakthrough relating to Dreyer's work, though, came with the heart-stopping discovery, in a cupboard in an Oslo mental hospital in 1981, of the original, uncensored print of The Passion of Joan of Arc – wrapped in cellophane, safe in canisters, pristine. A miracle. A resurrection. The reappearance of a film long considered 'lost', a film that had only previously been seen since its premiere in mutilated form, was an event as exciting as Raymond Carney's discovery of the long-lost, long first version of Cassavetes' Shadows (1959). Carney made his own contribution to the debate about Dreyer in 1989, with his book Speaking the Language of Desire: The Films of Carl Th. Dreyer, to all intents and purposes a (slightly shrill) response to Bordwell's book. Tom Milne was foremost among the few critics who dared to criticise, rather than eulogize Dreyer's work, but no critic working outside academia has done more than Jonathan Rosenbaum to increase awareness and understanding of Dreyer's work. His 2003 Guardian article on Dreyer* alone did more to correct common misconceptions about Dreyer than scores of subsequent theses and reviews. Not for nothing did Godard name Rosenbaum heir to James Agee's crown as America's finest critic.

| New Prints and a New Cinephilia |

|

Despite the sterling work done by those mentioned above, and others too numerous to mention, it was the gradual emergence of new prints of Dreyer's films – including the discovery in Moscow, in 1960, of a nitrate copy of Die Gezeichnetten/Love One Another (1922) – that did most to consolidate his reputation. His stock seems set to rise to new levels following the recent release, in Eureka's Masters of Cinema series, of the magnificently restored, 'lost' original of The Passion of Joan of Arc. This lavishly designed labour of love gives us the opportunity to view the film in the form Dreyer intended us to see it, at both 20 and 24 frames per second. It also enables us to compare the original silent version that Dreyer preferred with three sound versions, including the notorious 1951 Lo Duca version so widely circulated and so deeply detested by Dreyer. The Masters of Cinema series continues to set the standard for the introduction into our homes of the kind of hallowed, haloed films we once sought in cinemas with religious fervour, while echoing André Breton's battlecry: "The Cinema? Three cheers for darkened rooms!" As Robert Ebert has suggested, canonical film lists ('even' the well-respected Sight & Sound 'Greatest Films Ever' one) are ultimately meaningless, but it is far from meaningless that most of the films on that list are now available to us all.

As film projectors were ripped out of cinemas the world over last year, we could console ourselves with the thought that a new cinephilia was emerging; a love of cinema that retains its nourishing base in thriving film clubs, surviving cinemas, and the festival circuit, but which increasingly feeds on our capacity to watch films at home, view them at leisure, and discuss them online. In preparation for this piece I put my life on pause, read a few books, and watched more than a few films. To my eternal regret, I had been out of town for the British Film Institute's Dreyer retrospective early last year; now was the time to catch up. At one point, during a second viewing of Gertrud, I was struck by three thoughts. Firstly, that we can now programme our own festivals and select our own double bills (watching Vampyr after Gertrud, say, and vice versa). Secondly, that many of us in the complacent and callous West can, even now, sit back in comfort, grow fat on peace, eat like emperors, dress like monarchs, and (or) effectively raid the library of Alexandria and the vaults of the Cinémathèque Française at will; if we choose to forget the rest. My third thought was that life is rich and various and some of us ain't half lucky.

Over the past decade, Criterion, Eureka, and the British Film Institute have already delivered exquisite DVD versions of Mikaël (1924), Du skal ære din hustru/Master of the House (1925), Vampyr (1933), Vregens dag/Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet/The Word (1955), and Gertrud (1964) to our doorsteps. These important releases have made films traditionally more talked about than seen available to all. Each of these releases arrived accompanied by authoritative booklets. More often than not, they contain commentaries among the extras. [A recommendation and request: please, if you haven't done so already, buy the Masters of Cinema DVDs of Vampyr, today, and listen to Guillermo del Toro's commentary, a master class in informed, enthusiastic film criticism.]. Those booklets and extras add to the information available online through individual enthusiasts and invaluable research resources such as The Criterion Forum, IMBD, Senses of Cinema, Sight & Sound, the websites of Dreyer aficionados David Bordwell and Jonathan Rosenbaum, and the peerless dedicated Dreyer website of the Danish Film Institute.**

Unfortunately, despite those reliable resources, the review coverage of those films has all too often echoed earlier misconceptions about Dreyer. Paradoxically, that may be because an increasing number of reviewers conduct their research exclusively online, rarely crosschecking facts in books and libraries. It may also be because the copy of online reviewers seldom passes before editors and sub-editors. It is definitely due to the self-perpetuating process by which films labelled 'great' are uncritically received and reviewed as such, that process by which canonical films impose their pre-ordained reputations and pre-established meanings on pre-programmed audiences, with the labelling operating to decommission critical faculties. Which is why, when all is said and done, there are still things worth saying about Dreyer and The Passion of Joan of Arc.

It long ago become a critical commonplace to claim that this or that landmark silent film 'invented' cinema or marked the moment at which cinema announced its arrival as an art form. Much of the coverage of the Masters of Cinema release of Dreyer's classic has followed that pattern. It has done so while simultaneously locating the film within chimeric notions of evolutionary, linear cinematic progress that deny the significance of revolutionary moments of rupture and bursts of radical innovation such as those delivered by Dryer. We do the vanguard directors of silent cinema a disservice if we accept that view without challenge. We honour his memory, and theirs, by recognising the debt he owed to his cinematic antecedents. And we do Dreyer a disservice if we fall to our knees in praise of his work without attempting to establish precisely what is nonconformist about the form and content of his work, and without recognising what he added to the resources of film language. Where misinterpretations and misrepresentations about Dreyer persist, we owe it to him to challenge them, so I will challenge those surrounding his upbringing, ostensible humourlessness and religiosity, relationship to the avant-garde, and relation to his actors.

| The Passion of Joan of Arc |

|

When Dreyer finished The Passion of Joan of Arc, after eight intense months of shooting, he launched a classic into film history. The film is as beautiful as it is strange. Among the many bizarre aspects of the film were Dreyer's expensive sets, built over four months, in a field in Petit-Clamart outside Paris, under the direction of designers Jean Hugo (grandson of Victor Hugo) and Hermann Warm (who was responsible for the Expressionist sets of Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). The distorted perspectives created by askew, angular doors, walls and windows were by no means the oddest aspect of those sets. Dreyer's cinematographer, Rudolf Maté, used the newly developed panchromatic black & white film stock, so in order that the cement exteriors appear white on screen they were tinted pink, while the plaster interiors were tinted yellow. It is often suggested that Dreyer recreated the houses, towers, drawbridge and church of medieval Rouen so that the actors might completely inhabit their roles. Actually, those pinks and yellows must have made working on the film a startling experience. They must also have generated many an interesting conversation in the local tabacs.

The sense of giddy madness surrounding the project can only have been increased by the holes that pockmarked the location. Holes for cameras were drilled in the pink and yellow walls. In addition, Maté dug numerous holes in the ground to facilitate the low angle shots his director demanded, and to which Dreyer mischievously referred as "the frog's prespective." The strange circumstances of the shoot, coupled with the extreme demands Dreyer placed on his actors, may well have created an atmosphere of nervous dread, but by all accounts a lively camaraderie prevailed among a happy, united crew. The set was jokingly referred to as "The Castle of Clamart" while those holes earned Dreyer the nickname "Carl Gruyère." Another on-set joke had it that Joan of Arc had been murdered twice; the second time by a Dane (Dreyer), a German (Warm) and a Hungarian (Maté). Cast and crew may have had to tiptoe gingerly to avoid falling into foxholes, but they obviously didn't feel the need to tiptoe around Dreyer. He was clearly not the humourless, sadistic director of common caricature, nor 'The Tyrannical Dane' described by Paul Moor in his influential 1951 Theatre Arts Magazine essay.

Actually, Ordet contains one of the funniest moments in film history. When the new Parson visits the Borden family, he is taken aback by the behaviour of mad Johannes, who matter-of-factly introduces himself to the Parson as "Jesus of Nazareth." Later, the Parson politely broaches the subject of Johannes's insanity with the latter's brother, Mikkel, who says simply, "Something happened." The Parson asks: "Was it love?" To which Mikkel replies: "No, no, it was Søren Kierkegaard." It is an immaculately timed joke at Dreyer's own expense and that of Scandinavian philosophical seriousness, but it's a dry, subtle one. It is a Danish 'in joke' informed by an ironic sense of Kierkegaard's place in Danish culture, even by a shared knowledge of Grundtvigism, that Danish religious current that represented the human face of Lutherism. As such the joke passes many non-Danish viewers by, as much that Dreyer achieved does. We catch a more obvious glimpse of Dreyer's dry sense of humour in a moment, in Jonas Mekas's 1965 short film portrait of him, when his eyes glisten with the kind of tearful laughter that bubbles up from deep within the soul. Such moments may prove nothing, but they do hint at a Dreyer we seldom see and hear about. He was a gentle man with a gentle, impish sense humour. Yet he was also, to his credit, a sobre, serious-minded perfectionist, and those expensive sets would cost him, and us, dear. They are typical of the high standards he demanded of himself and others, standards that help explain why he made just five feature films between the arrival of sound and his death in 1968.

Dreyer had made eight films prior to filming The Passion of Joan of Arc in Paris. His previous film, Du skal ære din hustru/Master of the House (1925), a light-hearted love story about a tyrannical husband tamed by the kind-hearted family nanny, was shown the world over and had been a huge commercial success, particularly in Denmark and France. At the same time, a new French production company, Société Générale des Films appeared. Lavishly financed – by the combined wealth of a White-Russian-turned-Frenchman, Jacques Grinieff, Charles Pathé, and Leon Gaumont, and the Duke d'Ayen – it had the express intention of revivifying the flagging French film industry and producing big-budget epics to challenge Hollywood's hegemony. Having commissioned Dreyer in the Spring of 1926, they offered him a choice of subject – Marie Antoinette, Catherine de Medici or Joan of Arc – and an almost unlimited budget. The 7 million Francs Dreyer spent on The Passion of Joan of Arc was dwarfed by the 17 million Francs Société Générale des Films invested in Abel Gance's Napoléon (1927), but the producers were, nonetheless, enraged that Dreyer had spent so extravagantly on sets that barely appear in the film. They were also angered by Dreyer's decision to shoot in sequence (which entailed paying most of his large, often inactive cast throughout the intensive six-month shoot), and by Deyer's insistence on writing the script himself (after months of painstaking research, although the rights to Joseph Delteil's 1925 book on Joan had already been purchased). Even before The Passion of Joan of Arc failed commercially, long before Société Générale des Films went bankrupt in 1933, the damage was done and Dreyer's reputation as a profligate, finicky director was established.

That reputation helps explain why he made so few films, and why he failed to fulfil his lifelong ambition to make a life of Christ. His perfectionist proposals to recreate ancient Jerusalem with colossal sets, and to shoot the film in Israel, with a Jewish Jesus and a Jewish cast speaking Aramaic, cannot have helped. Nor can Dreyer's declared intention to break down ancient antagonisms between Christians and Jews. Such vision must have scared the hell out of potential backers. His cherished but unrealised 'Jesus of Nazareth' project belies the stereotype of Dreyer as a religiose and apolitical director, springing as it did from a fierce opposition to anti-Semitism. It was a conviction as deeply felt as his particular, peculiar brand of feminism and his hatred of religious hypocrisy. None of Dreyer's convictions were ideological or theological. He had witnessed anti-Semitism at close quarters when he was in Berlin to film Love One Another (1922), his 'gay' film, Mikaël (1924), and Master of the House (1925); while his sympathy with women and empathy for female suffering were, as we shall see, intensified by his feelings for his late mother. Love One Another (the German title for which translates as The Stigmatized) is a brilliant work of red-baiting, counter-revolutionary propaganda. It climaxes with a pogrom of the kind unleashed across Russia by Czarist counter-revolutionary propaganda before and after the 1905 Revolution. Although Dreyer was politically conservative (his only political allegiance was to the Radical Socialist Party, which was 'radical' and 'socialist' in name only), it one of the few silent films to tackle the question of racial hatred head on, and with radical realism at that. Dreyer was a complicated man full of contradictions whose complexes and paradoxes, as we shall see below, seeped into his films.

Dreyer's script and costumes were as sparse and cheap as his sets were lavish and expensive. The film owes a lot to the libraries of Paris. During the year or so of pre-production, while Hugo and Warm were studying (pink) mediæval miniatures in the Bibliothèque Nationale for design inspiration, Dreyer spent day after day, week after week, in the Bibliothèque de la Chambre des Députés studying Manuscript No. 1119: the original transcript of trial of Joan of Arc. Dreyer pored over the document until he practically knew the text by heart. He absorbed it to the point where, as he put it, all unnecessary elements disappeared. Finally, he was able to condense the 18-months of the trial into one day. Robert Bresson would later say: "One does not create by adding, but by taking away." Dryer had no intention to adding to the cut-and-thrust drama he discovered in the library. He would, henceforth, take a similar approach to all the texts he adapted.

Dreyer had no intention, either, of replicating the scale, scenes or costumes he had seen in such spectacular films as Gance's Napoléon and Cecil B. DeMille's Joan the Woman (1916) [In her wonderful book Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism, Marina Warner wittily says of the grand finale to DeMille's film: "The pyre piled up under Joan's frail body fills the entire marketplace. It would burn an entire army and would most certainly have set fire to the entire city."]. Nor was Dreyer interested in recreating Joan's military exploits – not least because Marco de Gastyne, who had the French army at his disposal, was filming his La Merveilleuse vie de Jeanne d'Arc (1928) at the same time. And yet, for the incendiary climax to The Passion of Joan of Arc Dreyer created crowd scenes as powerful as those that had astonished audiences when they watched Griffith's Birth of A Nation (1916), Lang's Metropolis (1927) and Gance's Napoléon. Even here, however, in what might appear a concession to the commercial and the spectacular, all was not what it might seem. For the closing crowd scenes Dreyer used a cast of (largely Jewish) Russian émigrés, as he had done in Love One Another, to heighten realism. Having fled their shtetls to escape pogroms, many among the cast would have readily identified with a crowd challenging English tyranny. What is more, Dreyer doesn't play the numbers game, rather, he achieves his ends through perceptual shifts similar to those created by Eisenstein in Battleship Potemkin (1925). In those climactic crowd scenes, Dreyer turned the crowd, and our world, upside down.

| Modernist Edge and Jagged Edges |

|

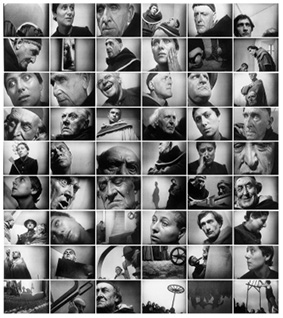

In his aptly rigorous shot-by-shot study The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, academic-critic David Bordwell says: "The need for criticism to recognize disunity and contradiction is nowhere more pressing than in the analysis of La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc. The polite respect accorded a classic must not obscure the plain fact of the film's strangeness. It is one of the most bizarre, perpetually difficult films ever made, no less disruptive and challenging than the early films of Eisenstein or Ozu." Dreyer's daring and invention produced a film that bristles with edgy modernism. Bordwell's own brand of patience and panache produced the book that Dreyer deserves. Where The Passion of Joan of Arc is concerned, Bordwell expertly demonstrates how Dreyer's use of high angles, low angles, and Dutch angles decentre the film, pushing characters out to the edges of the frame. He also describes the way Dreyer denies audiences conventional shot-reverse-shot eyeline-match satisfactions. Bordwell says: "Of the film's over 1,500 cuts, fewer than 30 carry a figure or object over from one shot to another; and fewer than 15 constitute genuine matches on action." Dreyer's rapid editing style, he says, disturbs our perceptions as surely as his disorientating disavowal of shadow, which dispenses with anchoring depth in favour of brilliant white backgrounds and skies. Most bizarre of all is the way dismembered, disembodied figures float within that limpid, luminous whiteness, "so that, swathed in ecclesiastical drapery, the judges seem not to walk but to glide or drift." The film is strange. It is little wonder that the film feels so modern – comprised as it is of elisions of thought and time, composed as it is of a series of jarring disruptions and disturbances that challenge comfortable and conventional ways of seeing.

The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer is a beautifully written, elegantly presented, extremely expensive book and a significant work of scholarship. It is a crying shame that Bordwell's gift for shard-sharp visual analysis wasn't rewarded with the timely reappearance of the original print. We can only imagine how frustrated David Bordwell must have felt when the pristine version we watch on the Masters of Cinema release was discovered, within a whisker of the publication of his bookIn an introductory "Note on Versions of Dreyer's Films," Bordwell says: "No filmmaker's work has been more mutilated for English-language audiences. Titles have been changed, intertitles re-written, shots reshuffled . . . I believe no complete print of the film has yet been found." Ouch! It is a shame, too, that Bordwell wrote his book before Drouzy's and the Drum's biographies arrived. Writing, as he did, without recourse to the biographical information Drouzy and the Drums supply, and without having seen the original version of The Passion of Joan of Arc, it was inevitable that Bordwell's book would arrive replete with lacunae.

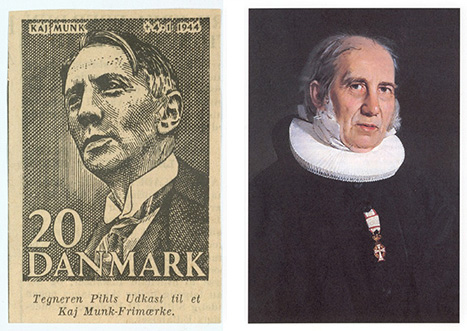

Those accidents of timing mean that although Bordwell succeeds in his declared formalist aim, the 'defamiliarization' of the film, he sidesteps Dreyer's formative years (a period that shaped his worldview and work), and has little to say about his ostensible religiosity. Thanks to Maurice Drouzy we are now aware that Dreyer's adoptive parents were not, as is often stated, 'strict Lutherans'. In fact, they seldom went to church. Dreyer himself said that he wasn't a religious man. In a 1956 interview with Film Culture magazine, Dreyer, speaking of the resurrection at the climax of Ordet, says, empathically: "I have not rejected modern science for the religion." We can no more reach a full understanding of the religious aspect of Dreyer's films than 'get' his Kierkegaard joke without reference to two Lutheran Pastors: philosopher N.F.T.S. Grundtvig (1783-1872) and playwright Kaj Munk (1894-1944). These nonconformist giants of Danish national culture were of huge significance to Dreyer, as they were to all Danes of his generation.

Grundtvig was a progressive thinker who placed an enlightened 'folk' or citizenry at the heart of nation building. It's easy to see why Dreyer, as a freethinking Danish autodidact, was drawn to Grundtvig's ideas of popular education and individual growth as part of 'the living word'. Munk's plays – particularly Ordet (1932) and his play on Grundtvig, Egelykke (1940) – left an equally deep impression on Dreyer. Munk was a less straightforward figure. Initially in thrall to anti-democratic ideas and an admirer of the Nietzchean Übermensch, Munk became a disillusioned, outspoken opponent of Mussolini, Hitler, and the Nazi occupation – which is why the Gestapo murdered him. Dreyer's aligned himself with Grundtvig and Munk in their opposition to forces on the opposite side of a schism within Danish Christianity: the intolerant, fundamentalist Lutherans of the Inner Mission influenced by Kierkegaard. Grundtvig and Munk were both at loggerheads with the established Danish Church, arguing for a worldly Christianity that embraced humour and the pleasures of the flesh, the profane as well as the sacred. What they felt was missing in the Inner Mission account of life is captured in the Danish word 'hygge', similar to the equally untranslatable German word 'Gemutlichkeit', which combines aspects of earthy camaraderie, cosiness, comfort, humour and hospitality. Dreyer's recurrent religious themes cannot be understood without the explanatory context of these crucial debates about national and social life in Denmark. Day of Wrath, for instance, which has been consistently misread as an allegory on the Nazi occupation of Denmark, was actually an expression of Dreyer's attachment to Grundtvigism and an intervention in that Danish debate. It is clearly significant that a framed portrait of Grundtvig features prominently in Ordet.

The problems with Bordwell's brilliant analysis of Dreyer's films, however, go beyond those gaps that can be filled in by analysis of the effect of Grundtvigism on Dreyer's work and those subsequently filled in by Drouzy. In Speaking the Language of Desire, Raymond Carney essentially argues that Bordwell's deconstructionist approach leads to an over-reading of the film. Bordwell, Carney suggests, overemphasises the degree of difficulty The Passion of Joan of Arc, and underestimates the importance of Dreyer's skill in handling actors and the film's consequent emotional impact. In his blunt rebuttal of Bordwell's approach, he comes to the defence of the film's 'star', Renée Falconetti (her daughter, Hélène, states that she has no idea where the errant, ubiquitous 'Maria' originated). Carney describes her as "the undeconstructable human being with a real body who is at the centre of the role, and who won't be reduced to . . . a mere semiotic function of a film's systems of artistic expression."

Bordwell's forensic formalist analysis undoubtedly increases our appreciation of Dreyer's precise, poetic composition. It emphasises Dreyer's sure grasp of tone, texture and timing. But Carney has a point. To take but two examples of the conventional pleasures the film offers, and that Bordwell overlooks: it is hard to think who else but Dreyer and Rudolph Maté, at that time, could have replicated the elegance of the establishing tracking shot with which the film opens, a slow left-to-right pan across a sparsely furnished courtroom, or that of the equally fluid tracking shot that passes down the line of judges whispering a question designed to catch Joan out. Nor can Bordwell's brilliant analysis of images contain the film's blood, spit and tears. The bloodletting scene in Joan's cell, the scene in which an inquisitor's spittle scars Joan's tear-stained cheek, the moments when flies land on Joan's tear-stained face; such emotionally charged moments lie beyond the reach formalist theoretics. In concentrating on the unsettling ways images operate in Dreyer's films, Bordwell largely ignores other factors at play in his career. To an extent his approach, productive as it is on many levels, works, as he himself says of others, "to block our understanding of the conflicting pressures – personal, industrial, aesthetic – that operate on that career." What is more, despite his considerable gifts as a film historian, Bordwell's concentration on the formal radicalism of The Passion of Joan of Arc downplays the debt it owed to earlier experimental advances. I'll attempt to plug those additional gaps below, by looking at the films and filmmakers who influenced Dreyer, and by considering how Dreyer's personal life affected his work, but, first, to faces, and close-ups.

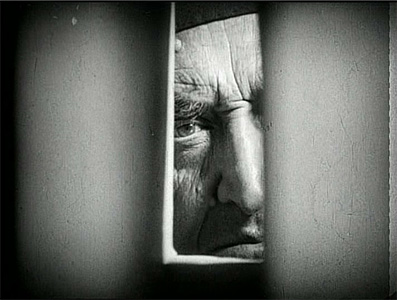

The Passion of Joan of Arc famously focuses on faces, in a way few films have done before or since, and we cannot fathom the film out without first focusing on what that means for it. Abraham Lincoln, Sartre, and others observed that we get the faces we deserve. Carl Dreyer's face was honest, intelligent, serious but soft, as marked by sorrow and suffering as his films. For The Passion of Joan of Arc he selected the faces he felt the film deserved: the judges are condemned by their fleshy, aggressive faces; Joan's suffering becomes real for us due to Falconetti's fragile, earthy face. Dreyer used professional actors extensively in his early films. Love One Another, for instance, featured Stanislavki-trained actor Richard Boleslawski, who would direct Garbo in The Painted Veil (1934) and Charles Lawton in Les Miserables (1935). In his later films, however, Dreyer would increasingly cast non-professional actors where he felt their facial qualities matched his idea of the characters they played. The importance of his skilled casting, choreography, and control of actors to the success of his films should not be underestimated. In his 1930 review of the film, Buñuel says: "Dreyer's genius resides in the way he directs his actors. In this sense the cinema has never before provided us with anything comparable." It was certainly a part of Dreyer's genius. In The Passion of Joan of Arc, he showed "the most sincere feelings possible" by filming the expressive qualities of the human face up close – sneers, tears, warts and all. Privileging emotional over visual verisimilitude, he cut back all that might distract our attention from faces: the sets, the script, the costumes, all bow to the human physiognomy. In his 1931 survey of the young art form, Cinema, the Observer's film critic C.A. 'Chestnuts' Lejeune says: "Dreyer's Jeanne d'Arc remains the type of great still photography on the screen."

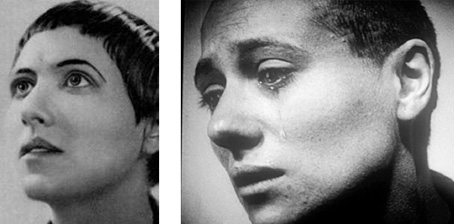

Dreyer's architectural use of close-ups is the first thing that strikes us about the film, particularly the repetitive, now iconic close-ups of 34-year-old Renée Falconetti as 18-year-old Joan. The trouble with icons, myths, and monumental reputations is that they hid behind their auras. This Masters of Cinema release affords us the chance to place them in the context of its day and drill for meaning. It also invites us to marvel at how modern the film feels. In a section on 'Historical and Chronicle' films in his book, Movie Parade, Paul Rotha says: "There is only one that had living quality, Dreyer's Jeanne d'Arc. That it had because it did not attempt a realistic construction of the past, but rather interpreted the past through modern eyes. If history is to be a subject of cinema, this method of Dreyer seems the only one possible. The camera and microphone are instruments too sensitively attuned to modern things for their penetrative power to be deceived by acting and costumes." Dreyer would have taken exception to those remarks as he prided himself on the authenticity of the acting and costumes. He responded sharply to suggestions that the steel helmets and horn-rimmed glasses worn in the film were anachronistic, pointing to documentary evidence proving their authenticity. Cocteau famously said of The Passion of Joan of Arc: "It seems like an historical document from an era in which the cinema didn't exist." Deyer achieved that effect by meticulous attention to historical detail, by rapid editing that works with evenly spaced intertitles to create staccato rhythm, by stripping the sets and script down to essentials (as he would consistently after Vampyr), by experimental camerawork, but, above all, by extreme close-ups that depict the range of human responses present, in all probability, at Joan's trial.

Dreyer's relentless use of extreme close-ups tightens the taut, claustrophobic emotional and psychological intensity of the film. Trapped, like Joan, within the confines of court, torture chamber and prison cell; pinned to our seats, as she is to hers, by the glowering expressions of hostile judges and soldiers; we experience her suffering with an almost unbearable intensity. Whatever one thinks of the function of close-ups in the film – and I'll come to that in due course – there is no denying that they add enormously to the success of the whole. But I'd like to put the cat among the pigeons at this point, by nervously asking whether we experience Dreyer's silent masterpiece intensely because of Falconetti's performance as Joan, as Pauline Kael insisted, or despite it, as Robert Bresson suggested? It is a question that feels as important to me as it will seem impertinent to others. I dare say it's a question few will entertain and that I'll remain within the minute, mute minority who find Kael's claim about Falconetti overstated, but I think it's one worth addressing.

One impudent question deserves another: if Falconetti's performance succeeds in the context of the late silent era, does it do so in contemporary terms, indeed, does any performance from that period? To which there are many answers: Antonin Artaud, Louis Brooks, Clara Bow, Lon Chaney, Charlie Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Lil Dagover, Marie Epstein . . . and so on. Otherwise, it's largely a question of personal taste, of demystifying Falconetti's performance, and of placing her in her era. As early as 1920, in an article on 'Swedish Film' written to coincide with the premiere of Victor Sjöström's Klostet i Sendomir/The Monastery of Sendomir, Dreyer says: "In the long-shot the actor had to make use of gesticulations and large facial expressions. The close-up, which betrays even the smallest twitch, forced the actors to act honestly and naturally. The days of the grimace were over." Sadly, they were not. Dreyer himself began to explore the expressive possibilities of the close-up in his early Kammerspiel films, notably in his second feature Blade af Satans Blog/Leaves of Satan's Blood (1920), but the long-shot was resilient. The period before synchronous sound was marred by stiff, stylised performances. It was a time of exaggerated, theatrical acting. Faces, unlike Falconetti's, were buried beneath make-up. The heightened expression of emotion invariably leaned toward the melodramatic. It was the age of images not actors. It isn't my intention to belittle Falconetti, rather, to consider the vital part she played in what makes the film succeed: the look of it, to which she contributes, and Dreyer's vision, with which she was a willing accomplice. It's a matter of separating the film from the myth of Falconetti for its own good.

Pauline Kael said of Dreyer, "Everything that son-of-a-bitch did was great." There is no reason why we can't agree with that eye-catching assessment while simultaneously taking issue with her fatuous, hyperbolic comment about Falconetti: "It may be the finest performance ever recorded on film.'' Kael's claim about Falconetti had clout. It had all the force of a self-fulfilling prophesy, and continues to exert an inordinate influence on the way Dreyer's film is received and reviewed. Her qualifying "may be," however, betrayed a sense of doubt (and how she must have wished she displayed such doubt after mauling Claude Lanzmann's Shoah . . . actually, she probably regretted nothing, ever, such was her outspoken, maverick genius). A browse of the internet reveals an astonishing number of lesser mortals locked in lazy certainty. I'm talking about those reviewers who either quote Kael verbatim, without explanation and without embellishment, or repeat variations on the theme: "Falconetti's performance is . . . widely considered/often described as/some say/seen by many as/said to be . . . one of the finest performances ever recorded on film." Whatever happened to film criticism? Come back Pauline Kael, all is forgiven. Kael, at least, allowed that it might not be. Godard's Vivre Sa Vie brooked no argument: when Anna Karina shed tears at the sight of Falconetti's tears she seemed to announce the final verdict on Falconetti. The tears of others make us cry. The camera loves all those it casts its light on. Case closed. No appeal allowed.

David Sterritt says in his book The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible: "Nana's tears are for Joan, for herself, and for a world in which the pitiless have a monopoly on power . . . Nana's double becomes the threatened and imprisoned Joan, so Karina's double becomes Maria Falconetti." Dreyer and Godard seem to ask: Who dare call himself human and not weep in solidarity with all four women and with all who suffer? Which feels like an order to be refused, not a question asked in good faith. On a personal note, I should say, lest I appear hard-hearted, that the tears of others make me cry too. I cry easily and often in cinemas. The greed, stupidity, and suffering of the world break the heart; cinema heals like balm. I go to cinemas to laugh at frivolous films; to unknot, unwind, unravel and, yes, to cry; but I also go there to think. Film melts frozen feelings but it is also, as Godard says in Chapter 3a of Histoire(s) du cinema, a form that thinks. When I first saw The Passion of Joan of Arc, as a film student, I found Falconetti's performance powerful but melodramatic; I also found myself thinking that this imperfect cinematic shibboleth deserved closer scrutiny. I'll never forget my tutor's cryptic reply when I babbled my views and asked him if he thought so too. He said there are two kinds of people: those who can happily await a delayed train on a wet winter's afternoon because their minds are brimming with thoughts, and those merely going through the motions of living, who stand there impatiently, bored and insentient. Make of that what you will.

Falconetti's fabulous face was a perfect fit for fable. It scorches the screen like a tintype photograph of flames. It burns itself into our memories. Dreyer was to say: "I don't know what it was I saw in her face, but I felt I couldn't find a better one anywhere. She didn't act for me; she just used her face." The question is: can we not value Falconetti's performance while still thinking that her face, the sets, the script, the camera, the cutting, and the supporting cast did much of her work for her? Falconetti appeared in just one film other than Dreyer's, a minor part in a minor film, La Comtesse de Somerive (1917). The theatre was her first love, and it was to the theatre she returned after working with Dreyer, turning down several offers of film parts to do so. Her background in theatre was, it seems to me, reflected in a theatrical performance in The Passion of Joan of Arc. She had trained at the conservatory of the Comédie Française under Eugène Sylvain (who would later play the role of Pierre Cauchon, the leading judge, in Dreyer's film) before building a stage career for herself during the 1920s, appearing, for example, in the stage adaptation of Collette's novel The Vagabond in 1923. 'Falco', as she was colloquially known in the Boulevard theatres, was popular and polished. After a brief, unsuccessful stint with the Comédie Française, she returned to light theatre, before being 'discovered' by Dreyer at Théâtre de Paris, where she was performing in La Garçonne, a modern comedy of manners by Victor Marguerite. Dreyer found her playing charming but "a bit giddy" and wasn't initially convinced he'd found his Joan. When he interviewed Falconetti at her Champs Elysées flat, however, he saw that "something" behind her make-up and Parisian poise, "a soul behind that façade."

When he made studio tests of Falconetti without make-up he was immediately persuaded. Interviewed by Michel Delahaye for Cahiers du cinéma, Dreyer recalled: "I found on her face exactly what I had been seeking for Joan of Arc: a rustic woman, very sincere, who was also a woman who had suffered . . . We always understood each other very well . . . It has been said that it was I who squeezed the lemon. I have never squeezed the lemon. I never squeezed anything. She always gave freely, with all her heart." Falconetti's commitment is beyond doubt. She gave her all to the role: she gave her very blood, she sacrificed her hair, and, in all probability, something of her sanity. There was an ambiguity and emotional depth to her face that, as Dreyer shrewdly observed, reflected inner torment and suffering. Hélène Falconetti has said that her mother was suffering mental health problems before she accepted the role of Joan, and those problems would markedly intensify after the film.

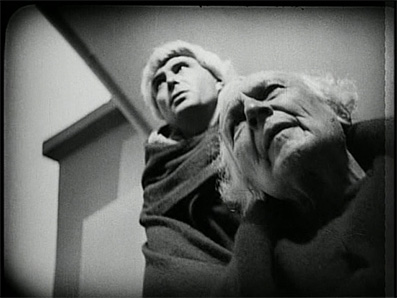

Falconetti was not the only member of the cast with such problems. Antonin Artaud, who plays the monk Jean Massieu, was a heroin addict, mild schizopheric, and manic depressive who had spent time in psychiatric institutions. Artaud is best known for his arguments for an avant-garde 'Theatre of Cruelty', elaborated in his book The Theatre and Its Double, in which the cruelty he referred to was that necessary to make audiences see realities they were in flight from, those realities hidden beneath the thin façade of civilization. David Sterritt says of the scene in which Massieu informs Joan that she may be tortured: "The sight of mad, tormented Artaud with doomed, tormented Joan – two figures at once transfigured and nearly crushed by enigmatic revelations – adds enormously to the resolution of this extraordinary moment." He might have inserted an additional reference to "doomed, tormented Falconetti" and added her to his "two figures": after this, her final film, she would become increasingly obsessed with mystical beliefs.

| Dreyer and Shaw's Saint Joan |

|

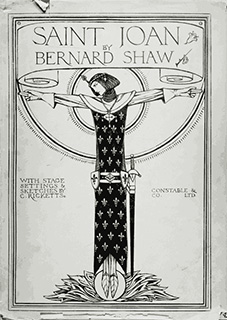

I am not arguing that Falconetti's state of mind had an adverse affect on her performance, on the contrary, the mental instability afflicting Artaud and Falconetti make his flawless performance and her flawed one all the more charged and impressive. The instinctive sympathy and affinity of fellow sufferers is apparent in the chemistry between the two on screen. The air of insanity on the set of The Passion of Joan of Arc also renders the discovery of the original print of the film in a mental hospital especially poignant and seems fitting given what might be considered mental instability in Joan of Arc. In a forensic, 62- page introductory essay to his 1923 play Saint Joan (which Dreyer must have read during his research), George Bernard Shaw defends Joan of Arc against charges of insanity. For Shaw, Joan's voices and visions can only be understood in the context of the Middle Ages, an active imagination, and a healthy evolutionary appetite. He calls her, "a sane and shrewd country girl of extraordinary strength of mind and hardihood of body." Apart from the reference to Joan's rural roots, it is a description that equally well suits Falconetti.

Shaw's interpretation of Joan's trial reveals interesting aspects of Dreyer's interpretation of it. Shaw compares it to the unfair trials of Roger Casement and Edith Cavell, and concludes that Joan got a fairer go in Rouen than Sylvia Pankhurst might have done in London. He points out that Pierre Cauchon, the presiding judge, was actually threatened by the English for being too fair with Joan, and describes how history was willfully rewritten, after Joan's rehabilitation, by those in thrall to the Doctrine of Papal Infallibility. Shaw says that Joan was essentially executed for "unwomanly and insufferable pretension." He calls her "the queerest fish among the eccentric worthies of the Middle Ages," "one of the first apostles of Nationalism," and "a pioneer of rational dressing for women." Shaw's reading of Joan would have appealed to Dreyer's feminism, even if it reflects badly on his commitment to a story, in the way of which historical truth was not allowed to get. And yet, Dreyer being a man of paradox, there are clear traces of Shaw's play, as well as of Théâtre Libre, in his film.

Throughout The Passion of Joan of Arc, Falconetti edges courageously across a tightrope pulled taut between the distant poles of clarity and insanity, cinema and the theatre, melodrama and naturalism. She was only able to do pull off that high wire act due to the safety net provided by Dreyer's direction and script, Maté's cinematography, Hugo and Warm's sets, and the performances of a superb supporting cast. That cast included not only Artaud and Silvain, but also Michel Simon – later to feature in such imperishable classics as Jean Renoir's Boudu sauvé des eaux/Bodu Saved From Drowning (1932), Jean Vigo's L'Atalante (1934), and Marcel Carne's Le Quai des brumes/Port of Shadows (1938). Although accusations of sadism against Dreyer are, as I said above, unfounded, he did go to extraordinary lengths to elicit performances of precision and power from his actors. He filmed in sequence and in silence, often behind screens and at night, in order to achieve the highest levels of concentration from his actors. He insisted his actors appear without make-up, that they be tonsured and grow beards where appropriate, and that they speak the lines from the trial transcript aloud the better to inhabit their parts. And, of course, he insisted on the shearing of Falconetti's hair.

Dreyer describes his method of constantly reworking scenes with Falconetti: "We would take have a bad take from the day before projected. We would examine it, we would search and we always ended finding . . . some little fragments, some little light that rendered the right expression . . . it was from there we would set out again, taking the best and abandoning the remainder." This method of painstakingly revising scenes, daily, helped polish the performances and perfect the whole. It is a working practise reminiscent of that of the great poet Robert Lowell, of and to whom Randall Jarrell said: "You didn't write, you rewrote." It was a matter of commitment and patience. Frank Bidart might have been speaking of Dreyer when he says of Lowell, in his introduction to Faber & Faber's Collected Poems: "Look at his work with any closeness and you discover that rethinking work, reimagining it, rewriting it, was fundamental to him from the very beginning and pervasive until the end." In Dreyer's case the daily work of criticism and self-criticism resulted in ensemble acting of the highest order. Each frown, gesture and glare tells its own story. In one sequence, a sympathetic judge bows before Joan, looks and nods are exchanged between a Machiavellian senior judge and an English officer, the rebellious judge is then followed from the court by English soldiers, while a concerned judge looks on aghast. Those intercut images tell us precisely what is happening. This is typical of the measured, wordless way Dreyer constructed meaning through small movements and glances. An overemphasis on Falconetti merely detracts attention both from the finesse of the acting around her and Dreyer's subtle direction of a steady succession of superbly executed scenes.

| Bresson, Bardèche and Brasillach |

|

There are occasions when the judges glower, pout or puff out their cheeks with undue emphasis, but Robert Bresson went too far when he described the performances in Dreyer's film as "grotesque buffooneries." Bresson had his reasons. In his article on Dreyer in Commonweal magazine, Richard Alleva takes Bresson's idea a step further still and describes the film as a tale of angels and gargoyles: "The movie's greatness isn't a matter of realism but the way it turns it's characters into archetypes. The close-ups make Joan iconic and transform her antagonists into gargoyles." The performances were, in fact, generally perfectly choreographed and immaculately executed; each, Falconetti's included to a degree, rang with truth. Yet there's truth, too, in Bresson's barbed remark, "For want of truth, the public gets hooked on the false. Falconetti's way of casting her eyes to heaven, in Dreyer's film, used to make people weep." She was both helped and hindered by Dreyer's desire to achieve what he called 'metaphysical realism'. We are used to more realistic performances. Falconetti's performance all too often sacrifices subtlety for dramatic impact; it is a little too wan and wide-eyed, a tad too tearful and fey. It will be objected that Joan was trapped and facing death, therefore tears and terror were bound to be the dominant motifs of the film, but from a fearless warrior who'd emerged victorious from bloody battles we might still expect less submissiveness and greater defiance, less salt and more bite.

As someone said of Florence Delay's performance in Bresson's Procès de Jeanne d'Arc/The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962): Bresson's Joan keeps her eyes down, not just to show modesty before God (and that despite Bresson's atheism), but to signal that she was not Falconetti. Bresson's version of the trial of Joan of Arc matches Dreyer's stride for stride, but it is Jacques Rivette who has given us the most complete, realistic account of her life, in his monumental two-part Jeanne la Pucelle: 1.Les batailles 11.Les prisons/Joan the Maid (1994). Rivette's film is as rigorous as Dryer's and Bresson's but his detailing is more authentic. He also allows us both Joan the fearless warrior and Joan the defiant orator. The less said about Luc Besson's Jeanne D'Arc/The Messenger (1999) the better. As Rivette wryly said of the flagbearer for the 'Cinéma du look': "Personally, I prefer small, 'realistic' settings to overblown sets done by numbers, but to each his own. Joan of Arc belongs to everyone (except Jean-Marie Le Pen), which is why I got to make my own version after Dreyer's and Bresson's. Besides, Besson is a single letter short of Bresson! He's got the look, but he doesn't have the 'r'."

Perhaps we get closest to the truth about Falconetti's performance not by heeding Kael, but by listening to the opinions of critics working before the icon was placed on its pedestal and the myth of Falconetti was established. In their compendious 1938 survey Histoire du Cinema, Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach compare Dryer's film to Gance's Napoléon, "as a spiritual epic as opposed to a physical one." They say of Falconetti's performance: "Under the severe direction of Dreyer, Silvain gave a prodigious performance, while Falconetti exhibited a restraint and power which she was never to attain again. Whether she portrayed a convincing Joan of Arc may be debated. Physically she did, in the scene in which she appears haggard and tormented before the execution. But her mood throughout is one of suffering; there is nothing here of the optimism or the insolence of the real Joan . . . Here she is only a young, martyred saint and this arbitrary limitation of the character cannot be denied. Once it has been admitted, her performance provides some prodigious moments."

next>

Part 1 | Part 2 | Blu-ray details

*Rosenbaum's Dreyer piece: http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2003/may/30/artsfeatures

**The Dreyer website of the Danish Film Institute: http://english.carlthdreyer.dk/

|