|

Patrick and the simultaneously-released Snapshot are the first of currently eight Australian films licensed by Indicator which fall under the Ozploitation banner. Indicator have form in this genre, having previously released Roadgames, also directed by Richard Franklin, and Mad Dog Morgan. Certainly since Mark Hartley's 2008 documentary Not Quite Hollywood, Ozploitation has been very fashionable - so much so that it seems that you'd have to pass off a film as such for it to get a Blu-ray (or even a 4K) release nowadays, other than a few standard classics like Picnic at Hanging Rock or Sunday Too Far Away (on Blu-ray in Australia if not in the UK). Other leading films of their time languish on DVDs and/or SD streams or are even, like Newsfront, which beat Patrick at the 1978 Australian Film Institute (AFI) Awards, presently AWOL. That split between Ozploitation and more "respectable" fare is a faultline that appears more than once in the extras of this disc, and it might seem churlish of me when a film of considerable merit gets an exemplary disc release, and that's the case with Patrick.

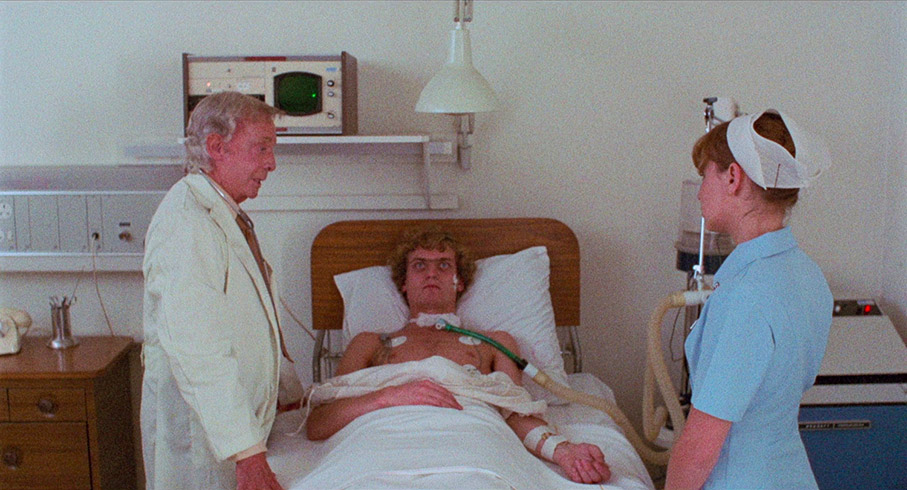

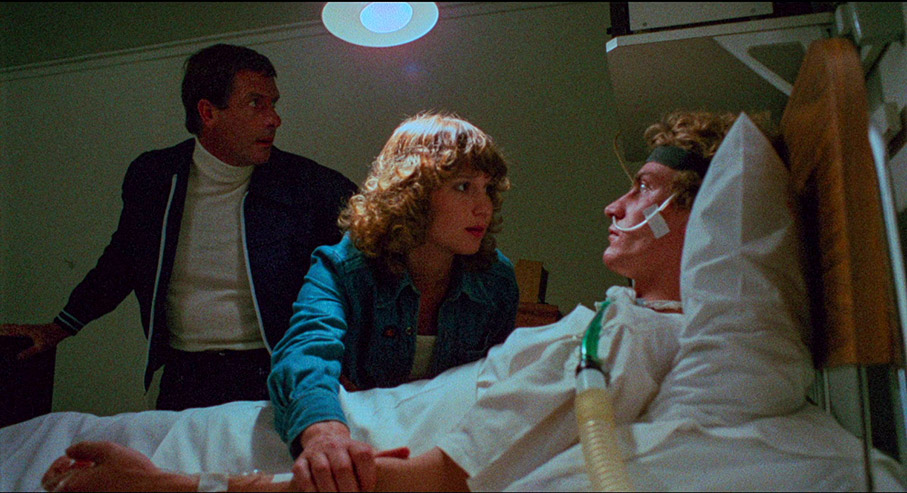

We begin before the credits with Patrick (Robert Thompson) listening to his mother and her lover getting along famously and finally he kills them by electrocuting them in their shared bath. Three years later, Patrick is in a coma, all but immobile other than occasionally spitting, and unable to talk. He is at the Roget Clinic, run by Dr Roget (Robert Helpmann) and Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake). Separated from her husband, Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligon) is hired at the hospital as a nurse and is given the task of tending to Patrick. She begins to sense that Patrick isn't brain-dead as everyone thinks but is alive and trying to communicate with her.

Patrick is a well-handled suspense thriller on the edge of horror/fantasy, with more than a few nods to Hitchcock along the way. With this film, his third feature, Richard Franklin found his niche, and his career as a maker of thrillers began. He makes the most of his restricted setting and pulls off some genuinely tense sequences.

Franklin (1948-2007) was born in Melbourne. He studied film at the University of Southern California and through that met Alfred Hitchcock when he invited him to speak at USC. The two men became friends. Franklin had been a huge Hitchcock devotee after seeing Psycho at age twelve and envisaged Patrick as a Hitchcock suspense thriller with an occult/supernatural angle. That was something that the Master never did in the cinema, though did come near it with the pilot for his TV series. Franklin returned to Australia at the end of the 1960s and began to work at the television company Crawford Productions, directing four episodes of Homicide, a long-running police show. (Homicide was shown abroad – in the UK, some ITV regions broadcast it.) Crawfords was a testbed for several future film directors, Colin Eggleston (Long Weekend), who had worked in the UK as a film editor in the mid 1960s, being one of them.

Franklin, in his contributions to this disc, refers to Patrick as his second feature film, his first being The True Story of Eskimo Nell (1975, retitled Dick Down Under in the UK so as not to be confused with the same year's Eskimo Nell, a British film directed by Martin Campbell). But in fact Patrick was his third film. In between the two he directed Fantasm (1976) under the pseudonym Richard Bruce. Although "Bruce" is interviewed in silhouette on the Umbrella DVD of Fantasm (on the same disc as the suavely-titled follow-up Fantasm Comes Again, directed by "Eric Ram", an equally incognito Colin Eggleston), you can see why he might have wanted to distance himself from it. It's a grubby and threadbare film aimed squarely at the dirty-mac brigade or whatever the Australian equivalent is, with a professor played by an uncredited John Bluthal talking about eight common female sexual fantasies, each of which is then depicted on screen. Yeah, right. Fantasm was initially banned by the BBFC and the most recent UK DVD by Nucleus Films is cut by some eight minutes, amongst other things removing the entirety of one fantasy involving being raped.

However, these films brought him into contact with Antony I. Ginnane, who had been a publicist on The True Story of Eskimo Nell and who produced Fantasm. Ginnane was a law student who became involved in Melbourne University's film society. There he wrote and directed a black-and-white 16mm feature, Sympathy in Summer, French-New-Wave-influenced and on the face of it considerably artier than the films Ginnane went on to produce. The film went on to be distributed as a supporting feature but made little impact. Other than the extracts in Nigel Buesst's (DP on the film) 2003 documentary Carlton + Godard = Cinema, I haven't seen the film and you'll need to visit the archive in Australia if you wish to do so. Ginnane made a connection with Franklin due to their shared love of Hitchcock (and in Ginnane's case Howard Hawks and John Ford too). Ginnane felt that the films being made in Australia as the industry revived in the 1970s, with government subsidies, were "respectable" period/historical pieces, often literary adaptations. He wanted to make films in recognisable genres, often with overseas stars, that could play internationally and not just in Australia with its relatively small population. In Franklin he found a kindred spirit and their next film together was Patrick. Although there is some state funding in the film, he sought private investments as well. Patrick was made for a lowish budget for an Australian film of its time, A$400,000. De Roche used his television experience to produce a story that could be filmed in a limited number of locations with a small principal cast. The film was shot over seven weeks with a pause for Christmas 1977. Robert Helpmann broke his back trying to lift Robert Thompson in the final scenes and spent the holiday period in hospital recuperating, but he was back in the New Year to finish the film with no delays.

Everett de Roche was an American expat in Australia working for Crawfords. He met Franklin on an episode of Homicide which he had written and Franklin had directed. While working by day on television scripts, de Roche moonlighted in the evenings on film work, and that was how he wrote Patrick. He was inspired by a story of a young man, also called Patrick, who discovered his wife in flagrante with another man. He decided to shame her by pretending to attempt to kill himself, by jumping out of a window...and missed the balcony and landed on a car below. He was tetraplegic as a result and could do little more than spit...though he still had sexual function and hospital nurses turned a blind eye to his wife giving him relief. Much of this story ended up in Patrick, with the major change being that, instead of the suicide attempt, de Roche and Franklin lifted the back story of Psycho by having Patrick murder his mother and her lover.

One side-effect of de Roche's inexperience in feature films was that his draft was too long, resulting in a film which in its first cut ran about 140 minutes. This was reduced to the final length (in Australia anyway – see below for more about alternate versions) of 113. The deleted footage no longer exists. You can see Ginnane and Franklin's wish to make the film seem more universal and unspecifically Aussie, as while the setting is clearly Australia and specifically Melbourne (the clinic's letterhead has the address as Armadale, which is a Melburnian suburb), the cast's accents are mostly English or the variety of Australian accent that is close to English, nothing at all broad. There's really only one Aussieism I picked up: see below when I discuss alternate versions. The lead, Susan Penhaligon, was English, and Julia Blake was born there. The most English-sounding of the lot, Robert Helpmann, was actually Australian – born in Mount Gambier, South Australia – but had worked extensively in England as a ballet dancer as well as an actor, his best-known role in the latter capacity being the Child Catcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), which scarred many a childhood.

Jenny Agutter (who had Australian form thanks to Walkabout and who would make another trip Down Under for The Survivor in 1981) was approached to play Kathy but she was unavailable and suggested her friend Susan Penhaligon for the role. Penhaligon (born 1949) had made some films in the UK but was better-known on television. The 1976 serial Bouquet of Barbed Wire (an ITV show - not made by the BBC, just to nitpick, as in the extras both Ginnane and Stephen Morgan get this wrong) made her a big name, and Ginnane thought that having her in the cast would aid in a UK television sale. That did in fact happen, indeed to BBC2, who first broadcast Patrick in 1984 in the second of the six Australian seasons they broadcast in the 1980s. Her career since has almost entirely been on the small screen. One controversy that has often attached itself to Ginnane's productions is his liking for casting non-Australians, which sometimes brought him into conflict with Australian Equity. While Kathy speaks in her actress's English accent, and there's a hint that she's not meant to be Australian (Matron Cassidy near the start refers to her working "in this country"), you do take the point that there were many Australian actresses who could have played the role, however well Penhaligon does, and she does it very well, easily commanding the audience's interest and sympathy. Helpmann is entertaining to watch in a performance just this side of ham, and he's given some of de Roche's best lines. (When asked how he came across a particularly expensive piece of medical equipment, he says "I won it in a card game.") Also of note is a neat study of martinetdom from the always-reliable Julia Blake. Robert Thompson is immobile for virtually the entire film and has no dialogue, but does what he has to do ably enough, namely look creepy. Franklin used him again in Roadgames but after that he seems to have left the industry. It does stretch credibility that Patrick's eyes are open throughout. Never mind the extra labour in keeping them bathed. The real reason is that Patrick looks much more unnerving that way and why quibble when the film works?

At just under two hours, Patrick is a slow burn but expertly paced, with de Roche and Franklin structuring the film around three main setpieces, at the start, in the middle and a jump scare at the end. There's a sly wit along the way with Franklin (at least in this version) in a pool scene playing on the similarity between Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring and John Williams's root-and-second (one semitone apart) theme from the then-recent Jaws. In terms of sex and violence, Patrick is a lot milder than many Ozploitation titles, and while strong language certainly featured in Australian films before this, there is none in this film. That didn't stop it being restricted to adults only in the UK on its first release, of which more below.

The music score is by Brian May (not the Queen guitarist and astronomer), who had worked with Franklin on The True Story of Eskimo Nell, and it was due to Patrick that George Miller approached him for Mad Max. The cinematographer was Donald (billed as Don) McAlpine. Born in 1934, McAlpine has had a very long career, still working as of 2023, and is undoubtedly one of the most distinguished DPs who came of age in Australia in the 1970s. He won AFI Awards (later renamed the AACTA Awards) for My Brilliant Career, "Breaker" Morant and Moulin Rouge!, the last of which he was also Oscar-nominated for. McAlpine and Franklin didn't always see eye to eye. At the time McAlpine was of the school whose best-known representative was the late Nestor Almendros, where if light wasn't natural it needed to be justified. In response to Franklin's demands for more expressionistic lighting, he would ask where it was coming from and how realistic it was. Franklin would reply that a film involving telekinesis was hardly realistic anyway. The two men didn't work together again. McAlpine clearly modified his stance when he, much later, worked with Baz Luhrmann.

Franklin next made Roadgames in Australia – again with imported lead actors, namely Stacy Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis – before heading off to Hollywood. He made a direct sequel to one of Hitchcock's most famous films, Psycho II. Making a follow-up to a masterpiece is a bold move, particularly when you begin by reprising one of the most famous sequences in film history, but Franklin's film is much better than it could easily have been. He continued to work in the USA, in the UK for Link (1986) and back in Australia. Richard Franklin died at the age of fifty-eight from prostate cancer. Everett de Roche, who became one of the most prolific and distinguished screenwriters of the Ozploitation era – he has a small acting role in Patrick – died in 2014 at the age of sixty-seven, also from cancer.

Patrick didn't do especially well in Australian cinemas, running into the cultural cringe where local audiences would rather see overseas rather than homegrown ones. It was nominated for three AFI awards, for Best Film, Best Original Screenplay and Best Editing (Edward McQueen-Mason). The winner in all three categories was Newsfront, which swept all before it that year. The film did sell very well in the market at Cannes, more so than the state-funded and costly The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (a historical literary adaptation based on fact, though violent enough to make it akin to Ozploitation, and another AFI Best Film nominee that year), which was in competition at the same festival. Patrick was released in many countries round the world, including the USA and the UK and Italy. The last of those is particularly significant, because that country produced an unofficial sequel.

This wasn't the first time that Italy had done this to a well-known overseas horror film: Zombie Flesh-Eaters was called in its native country Zombi 2, though it has nothing to do with Zombi, the local title for George A. Romero's Dawn of the Dead other than featuring shambling undead folk with a penchant for eating people. Patrick Lives Again (Patrick vive ancora, 1980) is a film I haven't seen, but contributors to this disc don't have many good words to say about it, and it is by all accounts considerably gorier than the original and with more gratuitous female nudity. At least, from the clips on this disc, they did find a fair lookalike for Robert Thompson. Franklin and de Roche had themselves produced a treatment for a Patrick sequel, but it was never made.

But there was more. In 2013, after directing Not Quite Hollywood and other documentaries, including several extensive making-of pieces for classic Australian films, Mark Hartley debuted as a fiction-feature director with a remake of Patrick. Antony Ginnane again produced and there's another crew link in that costume designer Aphrodite Kondos was the wardrobe standby for the original under the name of Aphrodite Jansen. The leads are played by Charles Dance (Roget), Rachel Griffiths (Matron Cassidy) and Sharni Vinson (Kathy) in that billing order. Further nods to the original include Kathy's ex-husband Ed having the surname Penhaligon, and Susan of that name is an uncredited telephone voice. Also, Rod Mullinar is again in the cast. The difference between the two is much to do with the difference in genre expectations in the thirty-five years between them. Hartley's film is shorter at 96 minutes, it's digitally-captured in Scope (something of a default in horror films nowadays) rather than shot on film in 1.85:1, and while the score has as distinguished a name as Pino Donaggio behind it, with some of Brian May's original score included, it's used very insistently to enable the now-obligatory regular jump scares. There is a twist in that now Matron Cassidy is Roget's daughter. Violence, nudity and language are stronger. It went straight to DVD in the UK under the amended title of Patrick: Evil Awakens. While it's not a terrible film, it isn't a very distinguished one either. The original remains the best.

Patrick is a UHD and Blu-ray release from Indicator, spine number 430, both editions region-free. This is a review of the Blu-ray, from a supplied checkdisc and a PDF of the booklet.

The film was given an X certificate (eighteen and over) from the BBFC in 1978, which is stricter than other boards. Any violent/gory content would surely have been within AA (fourteen and over) bounds even then, but what may have swung it are some overt sexual references, such as Matron Cassidy's early comment about the orientations and paraphilias of nursing applicants she's found, and a few remarks about Patrick being capable of erections. In Australia it was and still is an M, meaning that it might not be suitable for under-fifteens, but still an advisory rating. In the USA, the MPAA unbelievably gave it a PG, which I very much doubt they would now, as the US cut of the film still included those sexual references. For its first outing on UK video in 1993, Patrick retained an 18 certificate, but it has been a 15 since 2004. Viewers should be advised that the film contains a scene featuring strobe lighting, which begins at 73 minutes (65 in the US version and 68 in the Italian).

Antony Ginnane says that Patrick has had more different versions than any film he has been involved with, and this disc contains three of them. The main one, and the one I'd advise watching if you only watch one, is the Australian theatrical version, which runs 112:30.

In the US, the film was cut (to 96:32 here) and redubbed into American accents. Franklin was involved in shortening the film, but he objected to the redubbing, as he had gone out of the way not to have too-strong Australian accents nor Australian slang on the soundtrack, and many of the accents were British or close to it. However, it seemed that even British accents weren't desirable for American audiences. The one overt Aussieism in the script – Matron Cassidy's comment that she is "boss cocky" of the hospital – becomes "boss lady". "Lift" becomes "elevator" and "Mummy" becomes "Mommy", but in fairness those are British usage as well as Australian. "Get stuffed" remains, but that's typed rather than spoken.

The third full version included is the Italian, which runs 101:54. This is dubbed into that language, presented here with optional English subtitles. Matron Cassidy's comment above becomes "I'm in charge here" and some sexual references are more overt. This version replaces Brian May's score with one from prog-rockers Goblin, best known for their influential and very loud music for Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977). Poor old Stravinsky gets replaced too.

Both of these alternative versions are really sometimes interesting curiosities and are there for completists and anyone studying the film. There were other versions too, and the credits of one of them is in the extras below. In his interview Rod Mullinar mentions seeing himself on screen dubbed into Thai. Ginnane in the booklet talks about a German cut and dub. The UK may have had its own version too, as the BBFC's cinema pass is logged at 109:59, and that running time – and 9892-feet length – is confirmed by the June 1979 Monthly Film Bulletin. The two-and-a-half-minute difference is too much to be explained by differing distributor logos, and if anyone knows what that difference is, I would be interested in knowing.

Patrick was a 35mm colour production, and is an unusual Australian film for having been shot on Agfa stock rather than the more usual Eastman, due to a deal that was struck to reduce costs. The transfer of all three versions is in the intended ratio of 1.85:1, which was pretty standard for Australian films of the time not shot in Scope. I haven't seen the film in a cinema, my only previous viewing being an Australian DVD, but I can't fault this transfer, which is derived from a 4K scan of the original negative. Australian films from this period often look grainy, and Patrick is no exception, but that grain is natural and filmlike and the colours are true and blacks solid. No complaints here.

The soundtrack is the original mono in all versions, rendered as DTS-HD MA 1.0. The menu does advise of some damage near the start of the US dub. That apart, there's not a lot to say about this: the sound mix is clear and well-balanced in its dialogue, music and sound effects. There are English subtitles on all three versions, hard-of-hearing for the two anglophone tracks and a translation of the Italian in that cut. I didn't spot any errors in them.

Audio commentary with Richard Franklin and Everett de Roche

Recorded in 2002 and playing over the Australian theatrical version, this commentary is billed as one by Franklin and de Roche, but it's actually almost entirely Franklin solo, with five minutes of de Roche edited in (at 46:33). Inevitably, as the extras on this disc were produced at different times and without any intention of their being put together in the same place, as here, there is quite a bit of repetition across the disc. De Roche's contribution simply repeats the story of his inspiration for the film, which I've summarised above. Franklin's contribution is much more substantial, even though he talks about de Roche's inspiration as well. He's very keen to display his Hitchcock-aficionado credentials, pointing out several references in shots to various of the Master's films. Franklin does tell some good stories, such as how he failed to recognise Julia Blake at the wrap party as she had been in character for the entire production from her first day to her last. This commentary is valuable as it's a record of two men who are no longer alive, even though de Roche's contribution is more or less redundant.

On-set interview with Richard Franklin (9:23)

The item begins with a scene between Susan Penhaligon and Robert Thompson being shot. Interviewed by film critic Ivan Hutchinson, Franklin talks about how this is a suspense piece, rather than an action piece, as he might have made for Crawfords, and emphasises that the film is intended to be Australian but not specifically so, aimed as it was for an international audience. Special effects buffs will be interested to know that the electric heater thrown into the bath was obviously not a real one, but used the same material that Star Wars pressed into service for its lightsabers. There's more about that in the interview with special effects supervisor Conrad Rothmann in the booklet.

On-stage interview with Richard Franklin (8:21)

We move on to 2001, and Franklin is interviewed on stage by Mark Hartley, during Cinemedia at the Treasury Theatre in Melbourne on 1 April. Franklin talks about Australian cultural integrity and claims not to have any, and places his own film as Mid-Pacific rather than Australian. He discusses Brian May, who by then was no longer with us (he died in 1997 aged sixty-two) and the American redub and the Italian version. He talks about his and de Roche's unfilmed sequel and also the Italian sequel which did get made, of which we see an extract. Antony Ginnane was nicknamed "Gucci" due to his taste for such suits and the white loafers Susan Penhaligon mentions elsewhere, so as to look the part of a Hollywood producer.

A Coffee Break with Antony I. Ginnane (17:56)

And that producer is up next, from 2009. This item begins with a spoiler warning for Patrick, so watch after the feature if you haven't seen it before. As a fellow Hitchcock fan to Franklin, he reveals that the I in his name doesn't actually stand for anything, à la Roger O. Thornhill in North by Northwest. He begins with his wish to make films with more universal appeal and his sense that funding for Australian films went too often to films which wouldn't play as well abroad. Otherwise, this is a runthrough of the key personnel in Patrick: Franklin for his use of storyboards (very Hitchcockian) and moving camera and use of a chair on set, which surprisingly wasn't usual in Australia at the time. Ginnane talks about how Helpmann didn't take time off despite breaking his back and how Susan Penhaligon was affordably cast. We also hear about how Franklin and McAlpine clashed on set. He also talks about the Italian sequel, which he found dreadful.

Not Quite Hollywood interviews (62:02)

Outtakes from Mark Hartley's documentary have provided a rich source of extras for several Blu-rays and DVDs from more than one label. There are five interviews here, all recorded in 2008, with a Play All option.

Susan Penhaligon (11:09) is up first. She says that she liked the script and another incentive was that she wanted to visit Australia. She was conscious that she could be seen as a Pommy taking an Aussie actress's job, and found Franklin something of a hard taskmaster, demanding retakes because Robert Thompson blinked. Rod Mullinar was a flirt. One legacy of the film was that she learned how to make a bed with hospital corners.

Rod Mullinar (7:50) highlights de Roche's contribution to the film. He did his own stunts, but the scene where he is trapped in a lift was uncomfortable, despite a lavatory being added to the set. (Having been trapped in a lift myself in my time, I certainly sympathise.) Helpmann asked on set if he could score some hash, likely initiated into the weed by his then rather younger lover.

Richard Franklin (15:05) is next, though inevitably much of what he says here overlaps with his other appearances in this disc's extras. As he had gone out of his way to have the on-screen accents as understandable as possible, he describes the American redub as cultural imperialism, clearly still a sore point for him. It was for Robert Helpmann too, who sued the American distributors over it. Franklin talks about the Italian sequel, for which he was flattered but which he found overly gory and offensive.

Everett de Roche (6:52), after detailing his inspiration for the film, talks about his writing process, involving first drafts written quickly at night. Richard Franklin would not let him see the American-dubbed version.

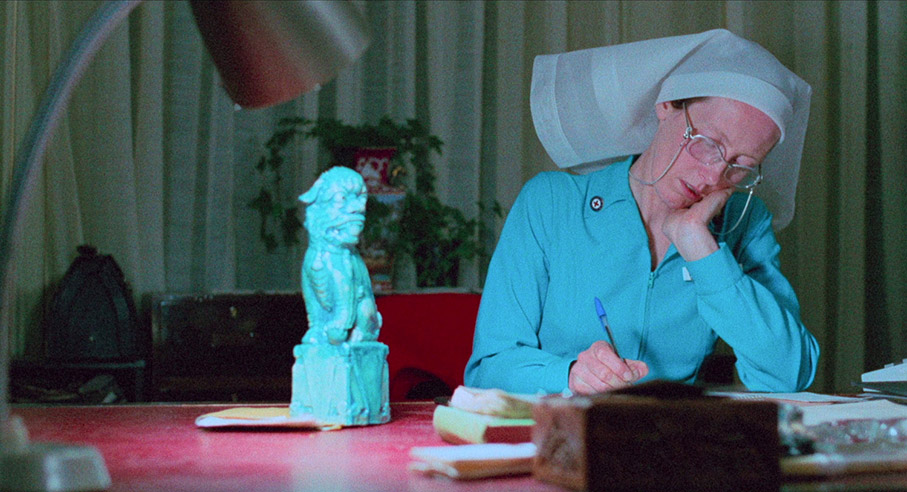

Antony Ginnane (21:03) saw himself as something of an outsider figure in Australia, due to his influences and wish to appeal to a wider audience than other local filmmakers. Patrick being a low-budget production, many of the crew hadn't worked on a film before, though some had done on television. Their average age was around thirty. His favourite scene is the one where a statue telekinetically moves on Matron Cassidy's desk unbeknownst to her. He was less bothered about the American cut and redub and points out that TV sales brought in more than the actual cost of the film.

Stephen Morgan: Shock Tactics (26:06)

Dr Morgan is a London-based Australian academic and Australian cinema specialist, the author of a forthcoming book on Ealing Studios' Australian productions of the late 1940s and the 1950s. As this item is much longer than the ten-minuter on Indicator's Snapshot disc, there's a sense that this Patrick appreciation is also a wider examination of Ozploitation and how it came about. As such it serves as an introduction to Indicator's range. A very thorough introduction it is too.

Morgan begins at the beginning of the 1970s, with local Australian film production in an all-time slump, but television thriving and Crawfords being as an incubator for future talent, Franklin included. Australia then (and often still has) a cultural cringe, a sense that their own films are by their nature inferior to those from other countries. It's almost that a film has to do well overseas before being accepted at home: for example The Babadook (2014) which opened middlingly in its native country but took off with its overseas acclaim and eventually jointly won the AACTA Award for Best Film. When the Australian film revived, its first commercial successes (and critical execration objects) were the Ocker comedies (the two Barry McKenzie films, Tim Burstall's Stork and Alvin Purple) which were later claimed as part of Ozploitation along with other genre films. This is in contrast to the "AFC (Australian Film Commission) genre", the more respectable genteel period/historical literary adaptations that Ginnane thought took up too much space in Australian cinema. Some directors worked both sides of the fence. Bruce Beresford went from the Barry McKenzie films to Don's Party and the very AFC The Getting of Wisdom. Meanwhile Peter Weir did make Picnic at Hanging Rock, a PG-rated arty historical literary adaptation par excellence (and, despite what Ginnane implies, very successful at the box office, if maybe not in the US), but he also made The Cars That Ate Paris which claims him for the Ozploitation fold. (Incidentally, Cars was another film redubbed into American as well as Patrick and most famously Mad Max.)

After this, Morgan continues with a specific look at Patrick, highlighting Franklin's change of direction from his earlier sex comedies (which didn't do well overseas due to humour generally not travelling well), and the contribution of Everett de Roche.

French Title Sequence Comparison (2:21)

Yet another version, compared via a split screen with the Australian. So we begin with a unique title card, "Highway Pictures présente" and a note that the film won the Grand Prix at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival, we start the film. As well as being in French, the credits are in a different font to the original.

Trailers and TV Spots (5:59)

With a Play All option, we begin with the Australian trailer (3:19). Australian cinema of the 1970s produced some lengthy trailers – the one for Picnic at Hanging Rock is four and a half minutes long – and this is no exception. Be aware of an extract from the strobe-lighting scene. After that we have the American trailer (1:47) and three American TV spots (0:31, 0:11, 0:11).

Image Galleries

There are two galleries, both of which are advanced or retreated via your remote. The first are original promotion materials, including stills (black and white and colour), front-of-house cards and newspaper and magazine ads and posters, including a British one for a double bill with the equally X-certificate Whispers of Fear, a film directed by Harry Bromley Davenport previously released in 1976. The second gallery is of behind-the-scenes photos, all in black and white.

Booklet

Indicator's booklet runs to 76 pages. After the cast and crew listing, we begin with "Australian Psycho: An Appreciation of Patrick" by Alan Miller. To get the vested interest out of the way, Alan Miller is a longstanding contributor to this site under the byline of Camus. The connection is that he worked with Richard Franklin on Link. He begins by mentioning that one spur towards Ozploitation was the introduction of the Australian R rating (seventeen and over) at the start of the 1970s. This was intended to alleviate one of the most draconian censorship regimes in the free world at that time, although cuts and bans still continued. It did enable film producers to up the sexual and violent content of their films, so as to make genre films comparable to those being made overseas. (Not all of them, though: as mentioned above, Patrick in Australia has always had the lower, advisory, M rating.) Miller then discusses Franklin's studies at USC and his contact with Hitchcock when he tried to obtain a copy of Rope to show. His appreciation of Patrick continues with the cast, beginning with Penhaligon and Helpmann, though he's in error in saying that Julia Blake was Australian-born as she was a Bristol baby originally. He also talks about Brian May and his Bernard Herrmann-influenced score, another way in which Franklin evoked the spirit of the Master. (Hitchcock was still alive when Patrick was released – I wonder if he ever saw it?) Miller is fair about ways that Patrick, remake as well as original, stretches credibility, and finally pays tribute to his late frequent email correspondent and friend.

Next, Richard Franklin takes the stage, via an extract from his unpublished autobiography, courtesy of his widow, Jennifer Haddon. He describes the making of the film, of which he is clearly proud despite a few flaws. His regular cinematographer Vincent Monton was unavailable due to making Long Weekend, so Don McAlpine came on board and as mentioned above they clashed.

Antony Ginnane follows, again from an unpublished autobiography. He talks about the setting up of Patrick and its making, with quite some detail about the film's experience at the Cannes marketplace along with its stablemate Blue Fire Lady, a children's film directed by Ross Dimsey. His comments that The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, being an expensive, dark and violent film with no big names as the leads, was a mistake to make was turned into a debate between him and the film's director Fred Schepisi, for which he later apologised. He acknowledges that Jimmie Blacksmith is a major Australian film of the 1970s and a critical success but never a commercial one. Patrick, on the other hand, was a commercial success, and Ginnane discusses its appearance in the AFI Awards, with Brian May's lack of a nomination being a disappointment. He also talks about the Australian critics' response to the film – some negative, others more positive – the Avoriaz festival and the various versions and dubs (he thinks the American redubbing was the right idea). This is a very long piece and undoubtedly too detailed for anyone not especially interested in film-industry concerns, but if you are interested in that there's much to appreciate despite an occasional sense of axes being ground.

Next up is Everett de Roche, in an extract from an interview by Paul Davies in Cinema Papers in 1980. Here de Roche talks about his writing process (ten days for Patrick, a script which was originally long enough to make a three-and-a-half-hour movie). He didn't research before writing, finding afterwards that the products of his imagination didn't need to be changed much, and saw the film as more of a monster movie than a love story, removing much of the latter aspect. And finally we have special-effects man Conrad Rothmann, interviewed by Dennis Nicholson, Peter Beilby and Scott Murray also for Cinema Papers, in 1978. As this is Rothmann's only appearance in the extras other than being mentioned by others, this is of considerable interest, particularly for anyone studying special effects work, and fairly technical it is too.

This booklet is a vital part of this release, so if you have any interest in these aspects or the film itself, you would be greatly advised to purchase a copy while Indicator's release is still in its limited edition, as it won't be available in any later standard edition.

Patrick is a film which has grown with age, setting Richard Franklin on a career making mainly suspense thrillers inspired by his beloved Alfred Hitchcock. Indicator's release is very impressive, auguring well for its future Ozploitation and maybe other Australian titles.

|