|

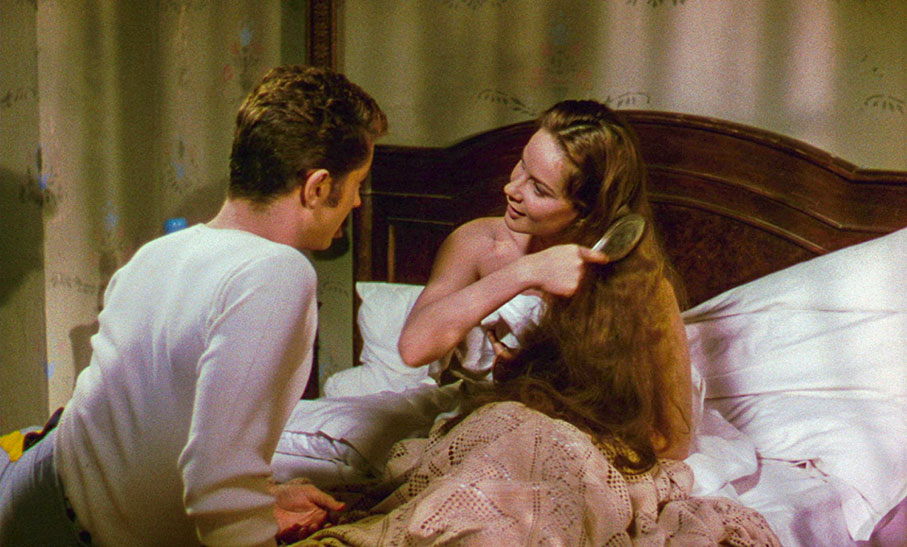

1866, during the Third Italian War of Independence between Italy and Austria. A nationalist protest led by Roberto Ussoni (Massimo Girotti) erupts in an opera house during a performance. Countess Vivia Serpieri (Alida Valli), unhappily married to the much older Count Serpieri (Heinz Moog), witnesses this and tries to conceal the fact that Roberto is her cousin. During the fracas, she meets Franz Mahler (Farley Granger), a lieutenant in the occupying Austrian army, and falls in love with him. Their affair begins in secret, even though Franz was behind sending Roberto into exile...

Senso. sometimes known in English as The Wanton Countess, released in 1954, was Luchino Visconti’s fourth feature film, his first in colour and his first in widescreen (for more of which, see below under “sound and vision”). It was based on an 1883 novella by Camillo Boito and has a complex set of writing credits: the screenplay was by Suso Cecchi d’Amico and Visconti, with credited collaborators Carlo Alianello, Giorgio Bassani and Giorgio Prosperi, plus Tennessee Williams and Paul Bowles providing dialogue for the English version, of which more in a moment.

Visconti’s roots were in the neo-realist movement, and his Communist sympathies contributed to Ossessione (1943), an unauthorised take on The Postman Always Rings Twice, and La terra trema (1948), his saga of Sicilian fishermen and their exploitation by the wholesalers they work for. Yet, beyond the documentary-style camerawork and the performances of non-professional actors, there was always something grandiose about his films, something operatic which reflected his additional career as a director in that medium on stage. This was also present in his third film, Bellissima (1951), a contemporary-set and to be honest very loud comedy. However, with Senso, we jump to a historical subject (and like his previous films except Bellissima, a literary adaptation), and a setting more in keeping to the one Visconti had grown up in, as the son of a Duke. That said, compared to some of his later films, Senso is more economical in running time and is actually quite naturalistic. It can’t count as neo-realism, given the historical setting and by being in colour and shot largely in the studio, but at times it’s almost a realist look at the people concerned, with lavish decors and costumes, while being a drama of an ultimately tragic passion.

Boito’s novella was presented as Livia’s secret diary. By opening the story up (with some voiceover narration by Livia remaining), the film has more of an emphasis on the war. The character of Roberto Ussoni is original to the film, as is the episode where Livia gives some money to Franz. This character was Rodrigo Ruiz in the novella; Visconti renamed him Franz Mahler after the composer, whose works he would later draw upon in Death in Venice (1971). Visconti originally wanted Ingrid Bergman and Marlon Brando for the two leads, but Bergman was not available (then married to Roberto Rossellini, who did not allow her to work for another director but him) and Brando was vetoed by the producers, so Farley Granger was cast instead. Visconti also approached Maria Callas to play Livia, but her schedule didn’t permit this, so Alida Valli took the role.

The film was shot in Venice and Rome, with the opening scene at the La Fenice opera house. Cinematographer G.R. Aldo, who had shot La terra trema for Visconti and three films by Vittorio De Sica including Umberto D. (1952), began shooting the film but died on 14 November 1953 in a car accident, aged just forty-eight. Australian-born, British-based Robert Krasker, who had won an Oscar for The Third Man (1950), took over and the film is credited to them both. This film was Aldo’s only work in colour. It’s not known who shot what, but the camerawork is suitably lushly coloured, if not overbearingly so. The film even pulls off some use of deep focus, a particular coup being where Livia leaves Franz in the foreground and hurries along the Z-axis of the screen, opening doors within doors in order to retrieve the money she will give him. Krasker and Visconti didn’t always see eye to eye, and when Krasker had to leave for another film as shooting overran, camera operator Giuseppe Rotunno shot the remaining scenes, including the final one. Rotunno became a regular cinematographer for Visconti, beginning with his next film, White Nights (Le notti bianche, 1957). Mahler in the closing scene is not played by Farley Granger, who had also fallen out with Visconti and had returned to America, so a body double was used instead. As usual with Italian productions, none of the dialogue was recorded live and actors spoke in their own languages on set, with the soundtrack post-dubbed. In Alida Valli’s case, she’s clearly speaking Italian in some scenes, but those with Farley Granger were conducted in English. That was the reason for the input of Williams and Bowles to polish the dialogue which would be heard in the English version of the film. As well as the Italian and English release versions, there was also a French one, supervised by Visconti’s old mentor Jean Renoir. That version isn’t on this release, and I haven’t seen it, but there’s a clip in the Visconti/Callas interview among the extras.

Senso had its premiere at the Venice Film Festival on 3 September 1954. It was up for the Golden Lion, but that was won by another Italian film, Romeo and Juliet (Romeo e Giuletta), directed by Renato Castellani and starring Laurence Harvey and Susan Shentall and also shot by Robert Krasker. That’s no doubt a judgement not endorsed by posterity, though it’s a film I haven’t seen. However, this is where the controversy starts, as Senso is a particularly complex example of variant versions, in running times and content as well as the languages spoken.

Even before the Venice premiere, the Italian censor had been at work, removing material for political reasons. Visconti’s original plan to tell the story of what he called “a bungled war, a war waged by a single class and ending in fiasco” had not found favour. According to Variety, the film played in Venice at 120 minutes, and the versions released in particular countries had different running times. The film was released in its English version in the UK. The BBFC records a time of 123 minutes in 1957 for the English version as The Wanton Countess, but the Monthly Film Bulletin in October 1957 gives a time of 100 minutes and the critic “A.T.” points out that the film had been shortened. He or she also had issues with the quality of the dubbing. There was an even shorter cut of the English version, 94 minutes. By 1982, Senso was in British distribution in 16mm, in a reputedly colour-faded copy, which ran 122 minutes. That year, the film was reissued in 35mm, but not a complete version as advertised, running 119 minutes.* This Blu-ray release contains what we have to take as the fullest available versions of the Italian and English versions.

Senso is released by Radiance on a two-disc Blu-ray, both discs encoded for Region B only. The film was cut for an A certificate in 1957 and was passed uncut (or rather the incomplete version submitted, as mentioned above, wasn’t cut) as Senso at PG in 1982, and the film retains that certificate for homeviewing.

The first disc contains the Italian and English versions (123:17 and 121:18 respectively, both times including restoration credits) in Academy ratio (1.37:1), with the on-disc extras. Disc Two has the Italian version in 1.66:1. Both versions have credits in Italian, and contain some dialogue in German.

1953, when Senso was shot, was the beginning of the widescreen era in Hollywood. The major studios began making films composed for wider ratios that year, and showing them as such in showcase cinemas, even before CinemaScope was launched with the release of The Robe in September. Non-Scope films were almost all shot “open-matte”, which meant there was additional image at the top and bottom of the frame if you saw them in 4:3, which you would have done on television or maybe in 16mm at your local film society. (That was the case for me for Senso: the BBC2 Film Club showing of 14 November 1987, introduced by John Francis Lane.) Within a year or so, Academy Ratio was obsolete at least as far as major-studio films were concerned and, within a few more years, commercial cinemas other than repertory screens and arthouses could no longer show it. This was also the case in Britain and to varying degrees in Western Europe. The upshot of this is that there are films from this changeover period which are assumed to be Academy when contemporary evidence (and that of your eyes, if you know what you’re looking for) tells you otherwise, and that’s often because many people are familiar with them from 4:3 television broadcasts rather than widescreen viewings in cinemas. When these films come out on DVD or Blu-ray they are sometimes presented in two or more different ratios. (To give one British example, The Dam Busters is widely thought to be an Academy film but there is plenty of evidence that it was shown in widescreen in cinemas at the time, to be specific in 1.75:1, which became the most common ratio for British films within a few years. Its premiere run at the Empire Leicester Square advertised it as being in “Metroscope”. StudioCanal’s collectors’ edition Blu-ray from 2018 contains both versions.) Well, you pays your money and you makes your choice, but my principle in the reviews I write is that a film should be shown in the ratio its makers intended it to be shown in, and other versions are rarely necessary. While widescreen films may well be “protected” for being shown open-matte (so studio lights, boom mikes and the like don’t make an unauthorised appearance), very few films are genuinely composed for two aspect ratios, let alone more. However, determining the correct ratio for a film in the changeover period is a matter of research (if contemporary paperwork survives) and should be done case by case as and when they are restored and/or appear on disc. Senso is clearly a widescreen film, given the surplus room over characters’ heads in shot, and I would have suggested having the English version in widescreen as well as the Italian, though it’s possible that such a master might not have been available to Radiance.

After all that, the transfer. The film was shot in 35mm Eastmancolour (processed by Technicolor) and the bold uses of colour come over very strongly, and grain is natural and filmlike. Screengrabs come from the widescreen version, other than a comparison shot with the 1.37:1 version below.

Both versions have the original mono soundtrack rendered as DTS-HD MA 2.0. As mentioned above, the film was post-dubbed and lipsynch inevitably wanders when the language on the soundtrack doesn’t match that spoken by the actor. Both tracks have a slightly hollow sound, without much in the way of ambience, but again that’s to be expected when none of the scenes were recorded live. The music, other than the opera scenes mostly by Anton Bruckner, mostly extracts from his Symphony No 7 in E Major, adapted by Nino Rota, comes over well. There are optional English subtitles but they differ according to the version selected. On the Italian version, it’s a standard translation track. In the English, they are hard-of-hearing subtitles, which also indicate when the dialogue goes into another language, such as the short exchanges in German.

Interview with Matteo Augello (18:59)

Augello is a London-based critic and fashion historian. He begins by citing Leonard Bernstein, that Senso is a great film to demonstrate Visconti’s sense of style, almost antiquarian in its obsessive attention to detail, which critics tried to square with his previous neo-realist works. However, Senso displays the same impulse in Visconti, where the detail on display is a function of studio artifice for the most part, given the historical subject matter. He was reconstructing history in the costumes and set designs, but this reconstruction was mediated via art and art history, which are after all the main visual records of the time is via painting. As such, Augello points out several of these references to artworks. For example, Livia’s dress in the opening opera scene alludes to a portrait of Empress Elizabeth of Austria by Franz Winterhalter, and we are shown the original to make this point. In a way, these references are “samples”, to use a much more contemporary term, and more recent films have sampled Senso in their turn: Augello mentions Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! Art experts are not often people you see on Blu-ray and DVD extras, so this does give a different perspective to the film, and this is a very worthwhile piece. I’m not sure I’d go along with him in wishing there was a remake of the film, though.

Interview with Luchino Visconti and Maria Callas (23:10)

This item, in Italian with optional English subtitles, comes from an edition of L’invité de dimanche, broadcast in April 1969 and appears to have been sourced from a homevideo recording. Apparently in a chat-show format, Visconti and Callas are interviewed, in French. Visconti says that he first became aware of Callas by seeing posters at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. As well as films, Visconti frequently directed for the stage, and that included opera – in fact, one of his three productions at La Scala in 1955 was one of La Traviata with Callas – and he speaks of “the magic of first-hand performance”. He says that at one performance he saw another leading soprano, Elizabeth Schwarzkopf in tears at Callas’s singing, something Callas didn’t know about. Visconti says that he was too shy to ask Callas to be in Senso so had to go via the production office – unsuccessfully as it turned out. We also see a lengthy extract from the film, which is the only evidence of the French version on this disc, though it’s sadly not the same in fuzzy black and white.

Luchino Visconti (60:35)

Also from Italian television, this documentary dates from 1999. It’s a straight-ahead account of Visconti’s life and career, with interviews from those who knew and worked with him. We see his childhood home at the Visconti Castle in Grazzano, which had been built by his father, the Duke of Grazzano Visconti, and which had a medieval village modelled around it. Luchino Visconti’s early career was as a horse-trainer, which enabled him to buy his own stables. Although he was homosexual, he had a devoted friendship with Coco Chanel and was at one time engaged to Princess Irma of Windisch-Graetz. During Wartime, he joined the Communist Party and worked with the Italian resistance. Before the War, he had worked in France with Jean Renoir on Partie de campagne (1936, released 1946) and Tosca (1941). As well as his films, his stage and opera productions are also discussed. His was a life and career too full to fit into an hour, and some films are skipped over. A large number of interviewees include Burt Lancaster (who says he was mostly cast in The Leopard due to his height, the character’s stature being a feature of the novel), Visconti’s former assistants Francesco Rosi and Franco Zeffirelli, regular screenwriter Suso Cecchi d’Amico, Claudia Cardinale and others, either recorded for this documentary or in archival footage. Visconti died on 17 March 1976, aged sixty-nine, and the documentary ends with footage of his funeral, attended by some of those interviewed here.

The documentary is presented in 1.33:1 as no doubt Italian television had not gone widescreen by then. This does mean that almost all the many film clips are 4:3, including some of the later films in Scope, such as The Leopard and Death in Venice, though those from Ludwig and Conversation Piece are letterboxed. The interviewees speak in their native languages, with fixed Italian subtitles appearing on screen where appropriate. Italian subtitles for the narration, Italian speakers and dialogue are optional.

Stills gallery

Ten colour stills, selectable via the Next button on your remote.

Booklet

Available with this limited edition is a booklet containing new writing by Christina Newland. It was not available for review.

Senso, in whichever version you see it in, was a key film in Luchino Visconti’s career. It was his first in colour, with a historical setting, and an early sign of his moving away from his neo-realist roots towards his lavish and colourfully operatic later work. I’m not sure of the need for two different aspect ratios in this edition, but the film is a visual feast, well served by this two-disc release by Radiance.

|