|

In spite of my sniffy contempt for celebrity culture, as a film fan I can't help but respond to the recollections of friends and associates of occasions when they have met and/or worked with filmmakers and actors whose work I admire. My co-reviewer Camus, a filmmaker by trade, is a fountain of such memories – if by some chance, you ever get to meet him, have him tell you the wonderful story about how he met and briefly worked with David Lean. The story that gave me my earliest such thrill, however, was revealed to me in disarmingly offhand manner by a man named Jim with whom I intermittently worked in my holiday job while I was at film school. A well-dressed elderly gent with an acerbic personality who generally liked to keep people at arm's length, he for some reason warmed to me almost from the moment we first met, and we began to hang out during our lunch breaks and took every opportunity to work together. Despite his mundane day job, Jim was also an accomplished artist, and regularly had his work exhibited in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, whose entry requirements were and probably still are intimidating. He did sometimes use sketch books, but preferred to work with easel and paints, making it easy for anyone to see what he was doing even from a distance. One day he was painting a street scene in London when he was spotted by a man who was crossing the road ahead and carrying a curious object. The man caught sight of Jim and came over to observe and comment favourably on his work, and chat for a while before politely excusing himself and continuing on his way. The man in question was Ray Harryhausen, and the object he was carrying was one of his self-created creatures, which he was on his way to his studio to animate.

For more than two decades, Ray Harryhausen was number one in a field of one, a rare example of an auteur who was not a director but whose films were and remain instantly recognisable as his work, not just for the stop motion animated sequences that he alone created, but for their stories, their characters, their look, their subject matter and their pacing. Directors, cinematographers, editors, composers and actors all contributed hugely to the individual films, but each served the distinctive overriding vision of Harryhausen and his supportive producing partner, Charles H. Schneer.

Harryhausen himself was first inspired to create his own stop-motion animations after seeing Merian C. Cooper's still astonishing King Kong (1933), whose stop-motion effects were created by the technique's first major pioneer, Willis O'Brien. The young Harryhausen thus arranged to meet O'Brien and show him his own animation models, and later got his first professional gig working for him on Ernest B. Schoedsack's 1949 Mighty Joe Young. A variety of animation and visual effects jobs followed, but it was when he met and teamed up with young Columbia Pictures producer Charles H. Schneer that the Harryhausen style as we came to know it really began to take shape. It was Schneer who realised the potential of a long-cherished Harryhausen project in which studios had shown no interest, and it was he who encouraged him to develop it into a feature. The film in question was The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, and it changed everything. This was Harryhausen's first film in colour (which presented its own very specific technical challenges), the first where his process of blending animated creatures with live action was given a name – Dynamation – and it marked a significant move away from science fiction and monster movies on which he had been working into Arabian fantasy. It was also the film in which the Harryhausen-Schneer house style as we came to know it was finally set in stone. It was also a notable box-office success, but crucially also had a significant impact of a whole new generation of wonderstruck young visual effects artists to be, all of whom went on to pursue successful film careers of their own, but who never forgot the man whose work first got them started.

I was born too late to have experienced The 7th Voyage of Sinbad for the first time on the big screen, an experience that was clearly life-changing for many future filmmakers and technicians of note. I still can't recall whether it was this film or the 1963 Jason and the Argonauts through which I was first introduced to Ray Harryhausen's work, but know for a fact that it kicked off a love affair that I have happily never grown out of. I do remember heading up to London and grabbing a front row seat for the opening week of Harryhausen's glorious swan song, Clash of the Titans, and afterwards buying every fanzine and fantasy themed publication that had articles on or even just images from the film.

Coming back to the Sinbad films after a break of several years, particularly looking as lovely as they do here, proved to be an exhilarating and inspiring experience. These films may not have had the life-changing impact they did on those modern-day special effects gurus who still go light-headed at the memory of seeing the Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad for the first time on the big screen, but they greatly enriched my appreciation of film and the artistry involved in its production, and they continue to thrill and excite me to this day. And I'm not alone here. When I announced that I had the Ray Harryhausen Sinbad films on Blu-ray, my girlfriend's face lit up like I'd just given her the best birthday gift in the world, and as we watched them together, the word that most commonly escaped her mouth seemed so appropriate on every level of its meaning: "Fantastic!"

One final observation before I get to the films themselves. In these times of inflamed bigotry, intolerance and rampant Islamophobia, it's interesting to note that these three beloved fantasy films all feature characters – whether they be heroes, princesses, villains or lowly crewmen – who are almost exclusively of Middle Eastern origin and of the Muslim faith, and that all three films feature repeated vocal tributes to the glory of Allah. I thus couldn't help wondering, should Indicator choose to release this box set in America, whether it would be subject to an immediate Trump ban and trigger panic-stricken wails of despair from right-wing news sites. Any foolhardy tourist carrying a copy in their luggage, meanwhile, would surely run the risk of having it seized from them at the airport, and find themselves labelled a potential threat to national security and subject to all manner of invasive procedures by over-zealous security staff. Just a thought.

| The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) |

|

There are a number of sound reasons why the first of the Ray Harryhausen/Charles H. Schneer Sinbad trilogy of films is widely considered to be the best. It's certainly my favourite, and here I make no apologies whatsoever for going with the popular critical flow. Want to know why? Well, let's start with the beginning.

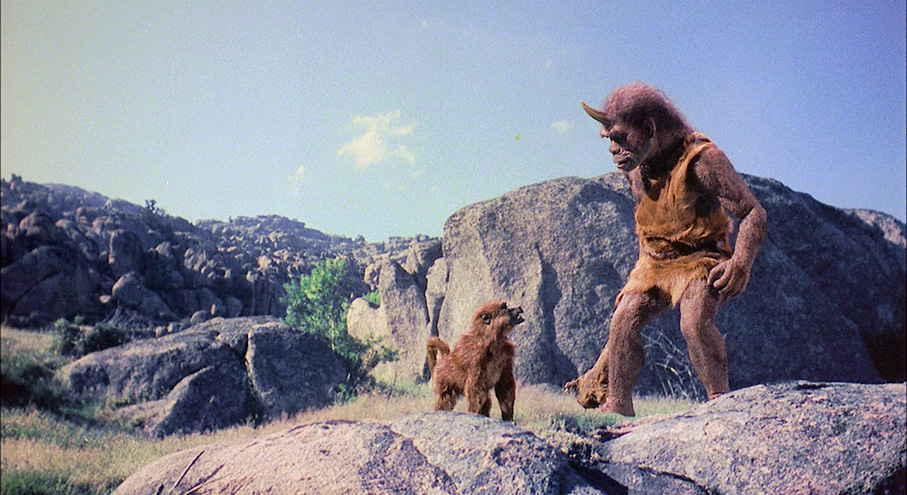

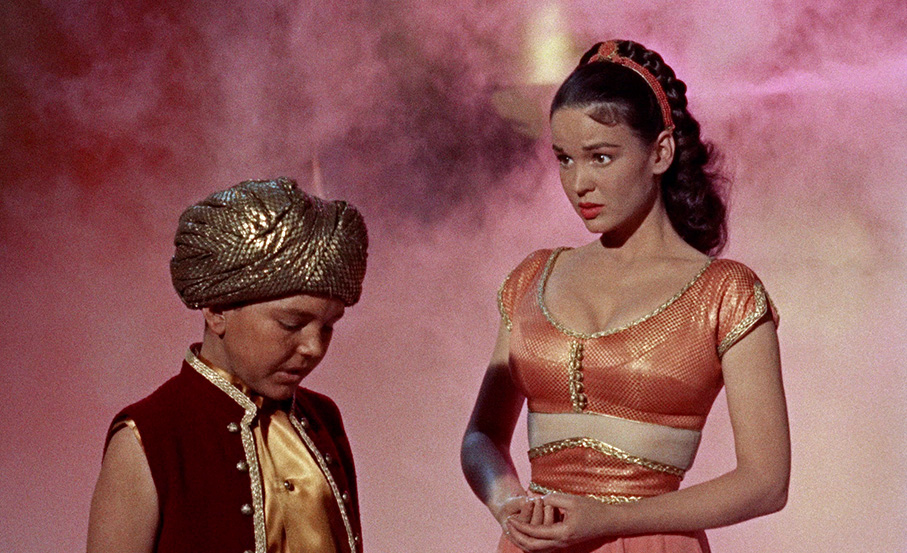

Despite having the task of introducing and bonding us to a character we're not yet familiar with from previous films – albeit one with a degree of popular culture fame – there's precious little build-up here before the action kicks off. As the opening titles fade, Sinbad and his crew are already at sea and lost in the foggy darkness. The crew are hungry and anxious, but there's one thing they're sure of – if anyone can get them out of this pickle, Captain Sinbad can. A short while later, Sinbad justifies their faith with his instinctive steering and his uncanny ability to spot the island of Colossa even before that poor sod stationed up in the crow's nest can shout a confirmation. There's food a-plenty there, but they've not been ashore long before a magician named Sokurah comes running out of a cave crying out for their help, pursued by a huge and single-horned Cyclops, courtesy of Mr. Harryhausen. Six minutes in and we're already treated to a showcase scene, and one of the like no filmgoer of the day had ever laid eyes on before. It's also here that we're introduced to the Genie that lives in the lamp that Sakurah is anxiously clutching, a character who is likely to come as a surprise for those whose image of a genie is based on Rex Ingram's towering and boom-voiced creation from the 1940 The Thief of Bagdad. Here, he's a young boy with an "oh gee" American accent, but don't let that put you off, as he's a lot more likeable than that probably makes him sound and later has a scene where you really get to feel for his fate. Charged with halting the Cyclops, the Genie throws up an invisible barrier that allows the sailors and Sakurah to escape in their boat, which is then overturned when the Cyclops hurls a huge rock in their direction. Although a powerful magician, it turns out that Sakurah can't swim for toffee, and in the process of flailing around in the water he drops the lamp, which is promptly recovered by the treasure-collecting Cyclops. And just in case you're wondering, Sinbad's titular seventh voyage has still yet to begin.

The ship heads back to Sinbad's home city of Bagdad, and we quickly discover that he is in love with the beautiful Princess Parisa of Chandra, and it is hoped by the Caliph of Bagdad that their upcoming marriage will ensure peace between their two nations. When the scheming Sakurah shrinks Parisa to a diminutive size, however, his actions anger her father, the Sultan of Chandra, who responds by declaring war on Bagdad. Assured that the only way to restore the princess to her original form is a potion that requires the eggshell of a Roc – a creature that only exists on Colossa, of course – the Caliph agrees to provide Sakurah with the boat he has requested and with Sinbad as its captain. To make up a crew shortfall, Sinbad recruits additional sailors from the Caliph's prisons, offering them escape from the hangman's noose if they join him on this perilous journey. What could possibly go wrong with such a plan?

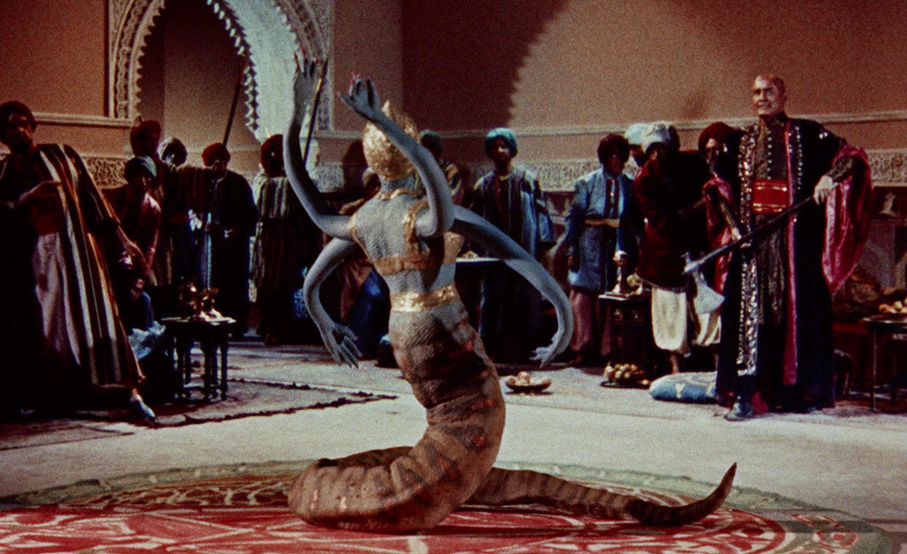

By this point, we've already been treated to Harryhausen's second showpiece scene, when Sakurah attempts to curry the Caliph's favour by transforming Parisa's handmaiden Sadi into a serpent woman as an entertainment at the pre-wedding feast, which goes a bit wrong when Sadi is almost throttled by her own independently murderous tail. This is one of the most impressive examples of the compositing of animation onto live action in the film, aided as it is by the more forgiving interior lighting and camera angles that suggest the softer background was created by a shallow depth-of-field rather than the photographic process employed to blend the images. Word has it that it was also Harryhausen's favourite sequence, and the creature itself became the basis for the terrifying Medusa in Harryhausen's final feature, Clash of the Titans.

When the convicts eventually mutiny and overpower Sinbad's crew, Sakurah pulls a rather neat fast one by cursing them in a manner that quickly comes to pass, something he pulls off not through the expected magical jiggery-pokery, but by dressing up his intimate knowledge of the locale in a cloak of mysticism. It's a trick along the lines of one employed by the time-travelling Hank in Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, who used his knowledge of an approaching eclipse to convince the superstitious locals he has darkened the sun. Here, the mutineers initially laugh Sakurah off, but in no time at all find themselves disabled by the wailing of nearby demons during a ferocious storm, allowing Sinbad to regain control of the vessel and steer them to Colossa, where he and his companions soon discover that their problems have only just begun.

A key reason The 7th Voyage of Sinbad works as well as it does is that it's first and foremost a rollicking adventure tale, one whose pacing and blend of action, tension and character scenes are in the sort of near-perfect balance that even this film's own sequels weren't quite able to replicate. Harryhausen's creature sequences are some of the most memorable of his career, and while striking for their design and artistry they are also genuinely exciting and always serve to move the story forward. The battle with the Cyclops, for example, not only score as a spectacle, it hooks Sinbad up with Sakurah, provides us with a demonstration the power of the magic lamp, gives Sinbad with a concrete reason for never wanting to set foot on Colossa again and Sakurah with one for returning there at all cost, effectively laying out the path that the story will subsequently take.

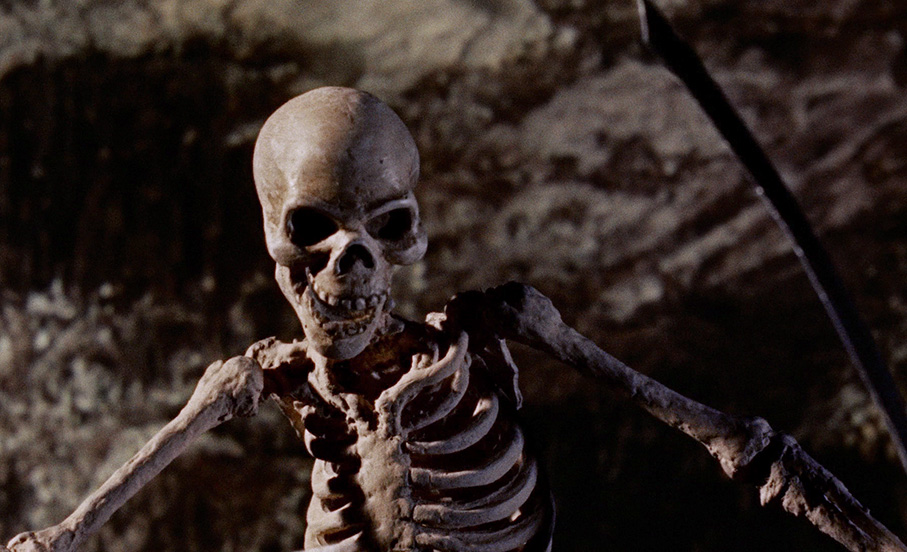

The Cyclops remains a fan favourite and has been cited by a number of prominent visual effects artists as the sequence that inspired them to pursue a career in this very specialised branch of film production. But it's Sinbad's later sword fight with a skeleton that both hooked and haunted me as a kid and continues to take my breath away as an adult. It's also here that the interaction between live action and animation is at its most striking. Think about this for a minute. The sword fight had to be choreographed to include moves made by a creature that would not be added into the film until much later, and lead player Kerwin Mathews was not just required to swing his sword in the right direction and at the correct moment (which itself presents a challenge when required to execute several moves in a row and also raise your shield to block incoming blows), but had to stop that sword in mid-swing each time as if it had made contact with his then invisible opponent's weapon. And yes, I'm fully aware that just about every actor who is pitted against a CGI monster today has to imagine its presence and respond accordingly, but where today all those concerned have years of experimentation and established technique to draw on, in 7th Voyage, Harryhausen was still writing the rule book, finding solutions to problems that had never before been encountered and in the process laying the groundwork for the generation of stop-motion animators that followed.

Everything works sublimely here. Kerwin Mathews makes for a likeable and energetic Sinbad, Torin Thatcher is deliciously malevolent and calculating as Sakurah, and the supporting cast enter fully into the spirit of the piece, responding to the actions of creatures they cannot see with the sort of conviction that convinces you of the threat they must nonetheless represent. It's directed with real verve by Nathan Juran and handsomely shot by veteran cinematographer Wilkie Cooper, but the icing on the cake is a glorious score by Citizen Kane alumni and Hitchcock regular Bernard Herrmann, whose rousing main theme and signature ominous bass woodwind and horns move into more experimental territory during a percussion-scored fist-fight and the later battle with the skeleton, where his use of xylophone and castanets almost creates the impression that the action is being accompanied by skeletal musicians excitedly tapping out rhythms on each other's bones.

Oh, I just can't be objective here. As far as I'm concerned, the 7th Voyage of Sinbad is a masterpiece of fantasy cinema, a genuinely groundbreaking work from one of film history's most imaginative and talented innovators, and one that that set the style for all future Harryhausen/Schneer collaborations. Others may disagree, but for me it was only topped by the duo's own Jason and the Argonauts in 1963, and having said that I know that it's nigh-on impossible for me to settle definitively on which of the two I love the most. Either way, the 7th Voyage of Sinbad is a marvellous fantasy-adventure tale and glorious entertainment of the sort that technological developments and changing tastes suggest, a little sadly, that we're unlikely ever to witness again.

| The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) |

|

The second film in Schneer and Harryhausen's Sinbad trilogy was a long time coming, and despite key similarities to its predecessor, it takes a somewhat different approach to its narrative structure. Where The 7th Voyage of Sinbad hits you with its first showpiece Harryhausen sequence just six minutes in, we're an astonishing 28 minutes into The Golden Voyage of Sinbad – about a third of its running time – before it does likewise. Don't get me wrong, there is some creature animation prior to this encounter in the shape of a small winged homunculus, but its role in the story is to sneak and spy on Sinbad's plans, and it thus lacks the imposing presence of the previous film's towering Cyclops. When that delayed first confrontation does finally arrive, however, it's a beauty.

The film once again begins with Sinbad and his crew at sea. When a small flying creature appears overhead, crewmember Omar takes a bow and tries to shoot it out of the sky. I exhaled loudly here, as while not a seaman myself I am fully aware of the superstition that killing an albatross can bring bad luck to a vessel, and while this clearly isn't an albatross, why take the chance? What has the poor little bugger ever done to you? When Omar misses his target – put off by the altogether more charitable Sinbad's protest – the creature drops the shiny object it was carrying onto the deck. It appears to be some sort of golden amulet, one that the creature tries vainly to retrieve and that Sinbad's second-in-command Rashid advises is probably evil and should be tossed into the sea. What does Sinbad do? He sticks a thread through it and wears it as a necklace instead. At this point my money was on Rashid to be running the ship in Sinbad's place before the day was out.

That night, the ship is hit by a ferocious storm and Sinbad is plagued by a dream featuring the amulet, the creature, a girl with a tattoo of an eye on her right palm, and a black-dressed man calling Sinbad's name. When the storm suddenly subsides, the crew discover that they've been pulled towards an island, and when Sinbad heads to shore he encounters Prince Koura, the man from his dreams, who claims the amulet is his and demands it be handed over. Sinbad outwits Koura by scaring his horse and punching his companion Achmed to the ground. Sinbad flees and Koura gives chase, but when Sinbad rides into the nearby city of Marabia, Koura backs off and rides away empty-handed. Here, Sinbad is greeted by the Grand Vizier of Marabia, who hides his face behind a golden mask, having been severely disfigured in a fire set by none other than nasty Prince Koura, an inferno that was designed to destroy wall paintings that contain the key to an as-yet unsolved mystery that could bestow great power on the one who can solve the riddle. Sinbad solves the first part with Indiana Jones-like guile, revealing a map that points him in the direction of the lost continent of Lemuria and the fabled Fountain of Destiny.

And there's more. In the process of prepping for his journey, Sinbad encounters merchant Hakim, who offers him 200 gold coins if he will take his deadbeat son Haroun to sea with him. Sinbad laughs the idea off ("I couldn't even use him for ballast!"), but when he discovers that Hakim's slave girl Margiana is the one from his dream, he agrees to take Haroun if he can also take Margiana as well. Given that Margiana is played by Caroline Monro and Hakim has upped his offer to 400 gold coins, I'm guessing he must really want to get rid of his son. Once Sinbad, his crew and the Vizier set sail, Sinbad frees Margiana from slavery and decrees her his equal, which gives him someone to fall for over the course of their journey. Pursued by Koura, Sinbad takes his ship into an area of dense mists and rocks that Koura's crew dare not enter, a move to which Koura responds by using his magical powers to bring the figurehead on Sinbad's ship to life, where it attacks Sinbad's crew and steals the map guiding them to their intended destination.

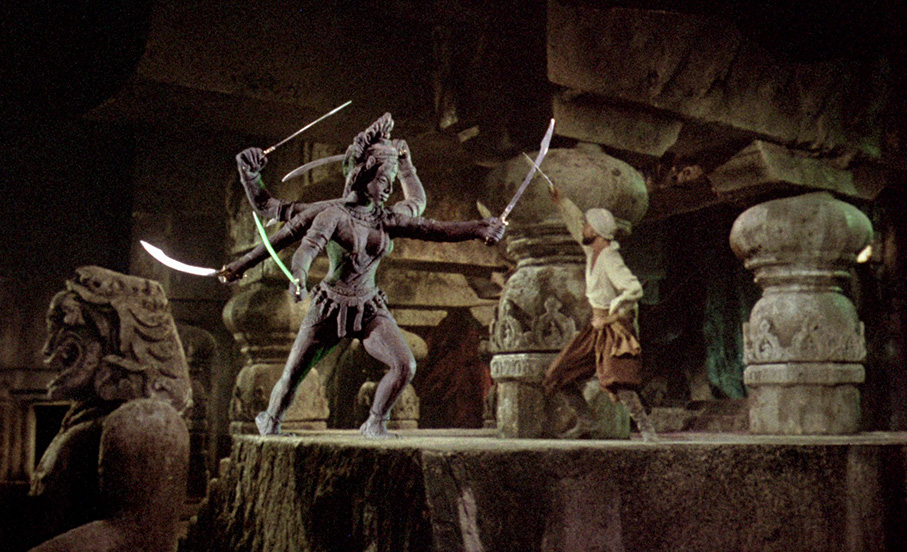

This is the scene we've waited patiently for, and it's just the sort of thing that first really hooked me on Harryhausen's animation. Don't get me wrong, I adore all of his mythical and even historical creatures, but as a child there was something innately disturbing about the idea of an inanimate human-shaped object suddenly coming to life. If it did so slowly, as if discovering for the first time that it had the power to move, then I was all the more rattled. My first and strongest memory of responding to this particular fear was the statue of Talos in Jason and the Argonauts, a giant metallic guardian of treasure whose first response to having its riches robbed was a small but ominously creaking turn of the head. For years after first seeing this (come on, I was really young!), I would pass nervous sideway glances at any statue or mannequin that I passed for fear it would suddenly turn its head to look at me and then come horribly to life to chase me. And so it is here, as the figurehead lowers its arm, slowly pulls its head away from the prow and look squarely at the seriously alarmed (and heavily drinking) Haroun. It then tears itself from the woodwork (the sound effects are always superb in Harryhausen's sequences), stands up and remains motionless until approached by a curious crewmember, whom it grabs by the throat and throws into the sea. Now you're talking. It's a hell of a sequence, but we're just getting warmed up here for the film's real show-stopper, when Koura brings a statue of the six-armed goddess Kali to life, which Sinbad and his crew are forced to do battle with. A brilliantly executed and genuinely thrilling blend of live action and animation, for me it's one of Harryhausen's most complex and astonishing scenes, one in which you absolutely buy into the threat that this multi-limbed, sword-wielding deity represents. As ever, Harryhausen also gets to have two creatures do climactic battle with each other when a centaur takes on a griffin in a climax that, while exciting and fabulously animated, can't quite match the unearthly sense of seemingly unstoppable danger posed by the almost mechanically lethal Kali.

If you're coming to The Golden Voyage of Sinbad primarily for Harryhausen's work, then it's possible you'll get a tad restless during that first-half-hour build-up. But put that on hold or give the film a second look (and these films really do reward multiple viewings) and you've still got a thrilling fantasy adventure tale, albeit one with a greater focus on characters and story than its exalted predecessor. And there are some really nice touches to the story and character development here, my favourite being the revelation that each time Koura uses his magical powers, it drastically ages a different part of his body, placing a limit on the number of times he can use them and adding a specific urgency to his need to reach the Fountain of Destiny, which has the power to restore his steadily crumbling youth.

The casting is first-rate. John Phillip Law remains my personal favourite Sinbad of the series, Tom Baker is splendidly menacing as the malevolent Prince Koura, Caroline Munro makes for a suitably seductive Margiana, and yes, that's a young and impressively naturalistic Martin Shaw as Sinbad's loyal and likeable first mate Rashid. Intriguingly, this is the only film in the trilogy where everyone speaks with a Middle-Eastern accent, giving the characters a continuity that is absent from the multi-accented approach of the other two films.

Beautifully shot and lit by early Bond regular Ted Moore, the film also boasts some terrific location and matte painting work, handsome production design from old hand John Stoll, and a full-blooded score from Miklos Rosza, all of which gives the film an epic sense of scale that belies its sub-$1 million budget. It may not have the frequency of creature conflicts of its predecessor, but as a fantasy adventure tale, it delivers on all fronts and certainly left me salivating for more of the same.

| Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) |

|

Despite a gap of only four years between this third film in the Sinbad trilogy and its immediate predecessor, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger arrived with a new Sinbad (Patrick Wayne) and a new director (Sam Wanamaker), and in common with The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, is not a direct sequel but a stand-alone work that can be watched and appreciated without reference to either of the previous films in the series. The core elements of the series are all present and correct – a dashing hero, a beautiful princess, an evil magician and a scene in which two of the film's creatures engage in mortal combat – albeit with a couple of interesting tweaks to the norm, notably the gender switch of the evil magician against whom Sinbad is pitted.

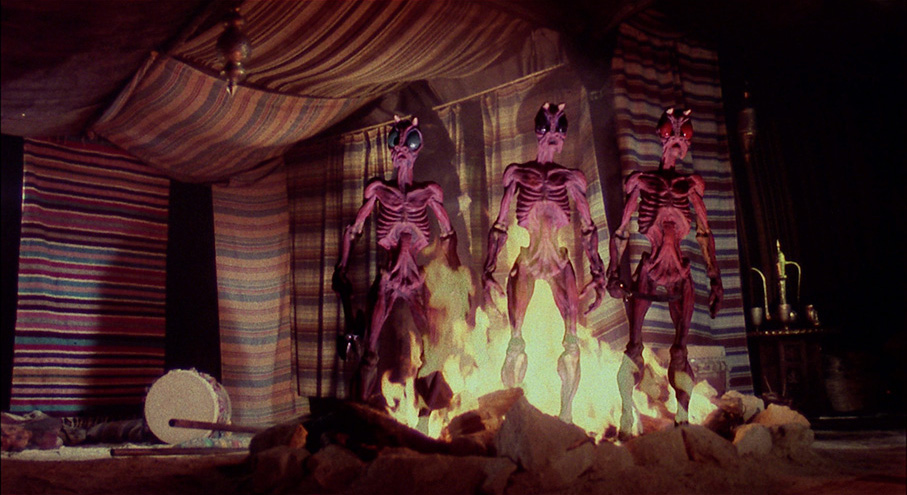

The story begins in the kingdom of Charak with the coronation of Prince Kassim, which is disrupted at the last second by a spell cast by Kassim's evil stepmother, Zenobia, who intends to put her own son Rafi on the throne instead. An unspecified time later, Sinbad arrives at the kingdom to seek permission from Prince Kassim to marry Kassim's sister, Princess Farah, but finds the city gates closed and no obvious sign of life within its walls. In the guise of a local merchant, Rafi tells Sinbad and his men that the city is afflicted with the plague and offers to entertain them until the morning when the nightly curfew will be lifted. Sinbad clearly doesn't completely trust this man, and his suspicions are confirmed when one of his crewmen is poisoned and Sinbad himself is attacked by Rafi, whom he quickly defeats. Before he can get any information from him, however, Zenobia turns up and casts a spell that prompts three demonic creatures to appear and attack Sinbad and his men.

Here the film takes its cue from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad by serving up the first battle between humans and Harryhausen creatures just seven minutes in. Drawing inspiration from the iconic skeleton battles in both 7th Voyage and Jason and the Argonauts, the demons here are genuinely unearthly creations whose grey skin is stretched over humanoid skeletal frames and whose horned heads are adorned with huge reflective eyes. These are the sort of creatures that Professor Quatermass might find inside a long-buried Martian spaceship, their demonic air enhanced by the flickering firelight that illuminates their presence. The subsequent swordfight with Sinbad is terrific, and only briefly undermined by the spectacular blue matte line that surrounds the pile of logs that will ultimately be used to defeat them.

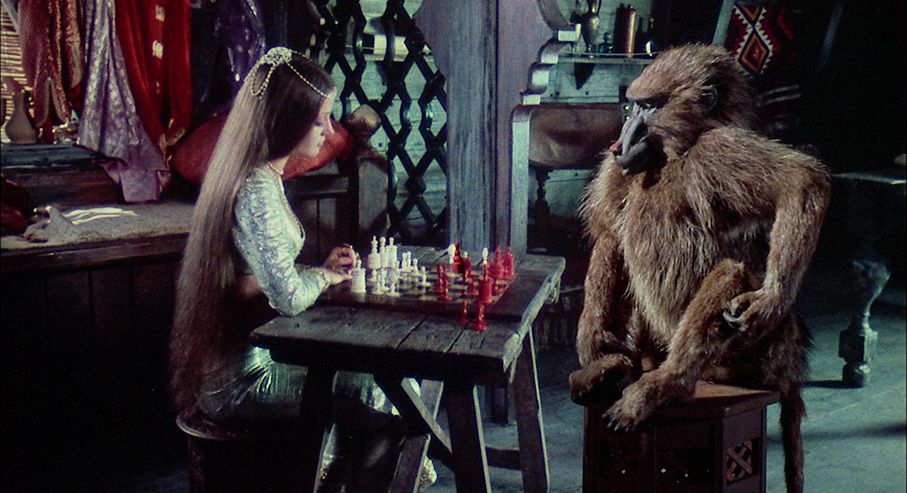

As the men make their escape, they are joined by Princess Farah and ominously observed by the cloaked Zenobia. The following morning, Sinbad learns just what happened in that opening scene, that Zenobia transformed Kassim, the rightful heir to the throne of Charak, into a baboon. Sinbad reasons that only a master magician would have a hope of reversing such a powerful spell, and legend has it that such a man exists in the shape of ageing Greek sage Melanthius, who lives a reclusive life on the remote and reputedly haunted island of Casgar. They prepare to set sail, but in a moment of fury, Farah lashes out at Zenobia and inadvertently reveals their plans, prompting her and Rafi to give chase in a boat rowed by a golden mechanical minotaur known as the Minaton. Sinbad and his crew make their way to Casgar, successfully navigate the dangerous waters around its shores and locate Melanthius, whose loyal daughter Dione takes an immediate liking to Kassim despite his baboon form, and he responds in kind. Melanthius suggests that that there may be a way to combat such sorcery, and that the answer lies within an ancient Arimaspi shrine in the land of Hyperborea. Initially reluctant, Melanthius agrees to accompany Sinbad, but the party's every move is being shadowed by Zenobia, who remains in close pursuit and becomes determined to reach the shrine before them.

Like its immediate predecessor, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger feels more focussed on the adventure than the showpiece scenes. Despite expectations created by Sinbad's early battle with the trio of skeletal demons, a couple of the creature encounters feel less fantastical than those in the first two films. These include the now extinct but historically documented sabre-toothed tiger from which we can assume the film draws its title, and an oversized version of an existing creature in the form of a giant walrus, a creature I found myself quickly sympathising with as it attempts to defend its territory against the nets and spears of Sinbad's crew. The giant wasp that Melanthius's foolhardy experimentation unleashes is a very different story (the crew claim it's a mosquito, which it bloody well isn't), as there can be few who do not duck and flap their arms at the appearance of a wasp of regular size and greatly fear its sting, making the prospect of being attacked by one that's a large as an angry dog with wings and a stiletto-sized stinger an easy one to respond to, particularly when the sequence in question is as excitingly assembled as the one here. Some of the most beguiling animation is of the baboon Kassim, whose every appearance is peppered with the sort of small and often engagingly human touches that suggest this was Harryhausen's favourite task on the film. When the crew later team up with a cooperative Troglodyte on Hyperborea – the animation of which is up there with Harryhausen's best – the kinship that develops between it and Kassim is as convincing as that of any human equivalent in the film.

The mission itself is leant a degree of urgency by the news that if Kassim is not crowed in the waxing and waning of seven moons then he will lose the right to be Caliph forever, and Melanthius's assertion that that the longer Kassim remains cursed, the more of his human qualities will be lost. Adding a degree of balance to this is a practical constraint placed on Zenobia's power, the source of which is a magical potion of which there is a limited supply, restricting its use and at one point backfiring on her, when the liquid is spilt after she has physically transformed and she is unable to ingest enough to fully return to human form.

Visually, the film is not quite as consistent as its predecessors, the main culprit being the decision to shoot the wider exterior shots on location and some of the close-up inserts in the studio against a matted background and with less naturalistic lighting, resulting in sequences that sometimes switch between realism and artificiality on a shot-by-shot basis. Patrick Wayne (that's Big John's boy) is an engagingly cheerful and energetic Sinbad, and Margaret Whiting walks a fine line of malevolent melodrama as Zenobia, but for me the show is stolen by Patrick Troughton's enthusiastic turn as the ageing Melanthius, his second outing for Schneer and Harryhausen following his role as the tortured blind man in Jason and the Argonauts. I also distinctly remember the bewitching teaming of Jane Seymour and Taryn Power (Tyrone's daughter) as Farah and Dione sending my teenage hormones hopping like bionic fleas, particularly the sequence in which the two take time out to sunbathe naked on a rock and have to scramble for their modesty when the Troglodyte first puts in an appearance.

There's so much to enjoy in each instalment of the Sinbad trilogy that it feels somehow criminal to start rank ranking them against each other, even in terms of personal preference. That 7th Voyage remains my favourite and Golden Voyage runs it a close second should not be seen as a negative reflection on Eye of the Tiger, which is still a richly entertaining and imaginative adventure tale with a string of standout sequences, strong story development, engaging characters and some of Harryhausen's most captivating creature animation. Oh man, what's not to love?

As the oldest of the films in this set, the natural expectation is that The 7th Voyage of Sinbad will have suffered the most from wear and tear and thus not look as good as its more recent brethren. Well buckle up people, as that's not what you get, not by a long shot. The result of a meticulous new 4K restoration by Sony, the 1080p 1.66:1 transfer on the Blu-ray in this dual format set is little short of spectacular. The sharpness and detail are intermittently eye-popping – and this is a film whose every costume and piece of set dressing benefits from that level of clarity – and the contrast balance is as close to perfection as you could hope for, nailing the black levels without sucking in any surplus shadow detail. A fine film grain is visible, which does sometimes coarsen a little on the process shots, which also sees the background detail soften slightly, but this is par for the course with this process and is never an issue. The only real concession to the film's age is a slightly warm colour palette, but this still allows for vibrant reproduction of brighter colours – check out the blues on brighter skies or the oranges and reds of the lighting in the dragon's lair – and there's not a dust spot or scratch or trace of damage to be seen. Watching the film with my girlfriend, I lost count of the number of times she exclaimed excitedly, "Wow! Look at that!" A superb restoration.

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad also boasts an impressive 1080p transfer in the film's original 1.66:1 ratio, this time from a 2K restoration, also by Sony. The warmly toned palette regularly bursts with colour when the costumes, locations and interior lighting command, really showcasing Ted Moore's sometimes painterly lighting camerawork. Although background detail sometimes softens a tad on the process shots, the film grain remains surprisingly consistent (the quality of film stocks had doubtless improved in the intervening years) and the contrast is once again spot-on. The image is clean and there are no compression issues, even in a sequence set in fog at night, a real litmus test for quality digital transfers.

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger also sports a hugely impressive 1.66:1 1080p transfer from a 2K Sony restoration, one whose detail is so sharp in places that you risk cutting your eyeballs. The contrast is once again perfectly pitched and the colours are often as rich as the contents of Sinbad's treasure chest. The image is largely clean, but there are a surprising number of dust spots and even the occasional scratch on some of the process shots, which I'm assuming were on the background plates or were picked up in the process of creating the original mattes and would require a frame-by-frame restoration to remove.

The original mono soundtracks for all three films have been supplied as Linear PCM 1.0 mono tracks, but we also have DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround remixes for all three films, and while the mono track is the one you would have heard in the cinema, I cannot recommend the 5.1 remixes enough. The music scores sound wonderful, the sound effects are more vivid and even the dialogue is noticeably richer and clearer. There is also some detectable sound separation, and the tracks have a vibrant, full-bodied feel that really do the visuals justice. Try watching a musically scored action scene with the mono track selected and then switching to the surround track midway through – you won't want to go back.

As you would expect, optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are included for all three films.

THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD

Audio Commentary

Licensed from Sony's 2008 50th Anniversary Blu-ray release, this commentary track is a valuable inclusion, primarily for the presence of the late, great Ray Harryhausen, who's joined here by visual effects artists Phil Tippett and Randall William Cook, Bernard Herrmann biographer Steven Smith, and compere Arnold Kunert. Essentially, this is Harryhausen outlining his working methods and techniques and explaining how specific sequences were created, while Cook and Tippett reflect on his influence on their careers (check out the other extras in this set to get an idea of just how inspirational his work was for these men and a good many other luminaries in their field) and Smith provides some welcome detail and background on composer Bernard Herrmann's contribution, some of which is duplicated in his stand-alone interview elsewhere on this disc. There's so much good stuff here it would be almost redundant for me to start selecting bits to highlight – just know that if you're a fan of the film then this is an essential extra, and there is plenty of material here that you'll not find replicated elsewhere in this set.

The Secrets of Sinbad (11:23)

Master visual effects supervisor Phil Tippett, the man who gave us ED-209 and Verminthrax Pejorative (look it up, people), reveals that he used to steal 8mm copies of Harryhausen films in order to watch them over and over again, and recalls how he met and became friends with the man who inspired him to pursue a career in visual effects. He discusses why Harryhausen preferred to work alone, the recognisable aspects of his animation style, and how he became an inspiration for the next generation of visual effects artists. He also describes him as "a fun guy, as long as you didn't ask him how he really did things."

Remembering the 7th Voyage of Sinbad (23:31)

A 2008 interview with Ray Harryhausen, who traces his career from his first interest in stop-motion animation, and breaks with his earlier secrecy about his working methods to outline the technical challenges presented by some of his most celebrated sequences and how he overcame them. In the process, he highlights a detail on one of the creatures in Golden Voyage that I hadn't picked up on, and a technical issue that hadn't occurred to me regarding the colour temperature of the film. A most welcome and informative inclusion.

A Look Behind the Voyage (11:52)

A 1995 Columbia Tristar featurette on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, with contributions from Ray Harryhausen, producer Charles H. Schneer and lead player Kerwin Matthews. Initially the focus is on Harryhausen and his early career, though this proves to be a prologue for discussion on various aspects of the film's production, all of which is of considerable interest.

Super-8 Version (31:16 total)

I'm starting to think that someone at Indicator has a big box of these tucked away in their loft. If you're new to the concept of cut-down, 8mm film versions of popular features of the day, then I refer you to my review of Indicator's release of The New Centurions, where I talk about them in more detail. Here, rather than a compressed version of the whole film, we have four separate extracts, which are presented as a mixture of colour versions with sound and silent black-and-white, whose dialogue appears as huge translucent captions that almost obliterate the picture.

Music Promo (2:23)

This one caught me completely by surprise. On the film's release, Columbia Pictures commissioned a 45rpm single titled Sinbad May Have Been Bad, But He's Been Good to Me with the intention that it be played in cinema lobbies and offered as prizes in competitions. It's the sort of song that was doubtless targeted to appeal to the younger viewers of the day, has nothing except the name Sinbad in common with the film it was written and recorded to promote, and has lyrics like, "He brings me many treasures, he knows just how to please." I'll just bet he does. Nowadays the studio would have no shame at all about plastering this all over the end credits.

The Music of Bernard Herrmann (26:52)

Music historian and Bernard Herrmann biographer Steve Smith takes on a useful trip through this hugely talented composer's career and covers in some detail what it was that made his soundtracks so special. He reveals that Herrmann initially turned down the offer to score The 7th Voyage of Sinbad but was immensely proud of his work on the film, and handily deconstructs the music for specific sequences.

Isolated Score

It's rare that I champion this sort of extra feature, but in lieu of a dedicated soundtrack album and given the brilliance of Herrmann's score, this one is seriously welcome. Sounds great, too.

Birthday Tribute to Ray Harryhausen (0:57)

A personal birthday message to Ray Harryhausen from Phil Tippett, who lists all of Harryhausen's films at a breathless speed, then sings Happy Birthday with a group of armed and animated skeletons.

Trailers x 3

This is Dynamation! (3:26) is an enthusiastic promo for the film's effects, some of which are deconstructed to give an idea how they were done. Cool. We get to see the trailer again in This is Dynamation! Commentary (4:47), where director Brian Trenchard-Smith introduces and comments on it for Trailers from Hell, and includes a recommendation for Harryhausen's book, An Animated Life. The Re-release Trailer (1:46) is a decent enough sell that focuses on the film's showcase scenes, of which there are many. The narrator certainly sounds enthusiastic.

Image Gallery

74 manually advanced slides of promotional stills and poster artwork.

THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD

BFI Interview with Ray Harryhausen and Charles H. Schneer (90:10)

We're warned up front that the quality of this audio recording of an interview conducted at the National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) in 1970 with Ray Harryhausen and Charles H. Schneer has some technical issues, but as the opening caption suggests, the content is far too valuable for anyone who cares to be bothered by that. This is all great stuff, and stands apart from the commentary on 7th Voyage and the Guardian interview on the Golden Voyage disc by way of Schneer's contribution, which is substantial, informative and often entertaining. My favourite story revolves around them having to sneakily shoot plates for It Came from Beneath the Sea of the Golden Gate Bridge from inside a bakery truck when official permission to do so was denied (I'll leave it to Schneer and Harryhausen explain why), and I laughed out loud at the idea that Harryhausen's response to Schneer's insistence that they needed to trim the budget of that film was to reduce the number of legs on his giant octopus by two. There's plenty more, all well worth hearing. Plasma TV owners will be pleased to learn that this plays as a commentary track on the film to avoid screen burn issues.

Golden Years (37:03)

The lovely Tom Baker talks about his early acting career and recalls working on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad with great affection, particularly his encounters with Ray Harryhausen – "It was so nourishing to be in a room with him" – with whom he subsequently became friends. He has a number of engaging stories about the shoot, and his journey from jobbing actor to building site worker to landing the career-changing role as The Doctor in Doctor Who is covered in enthralling detail. He does tend to shoot off at tangents when a new anecdote pops into his head mid-sentence, but full marks to those who shot the interview for letting it run without cutting any of this out, as it's always entertaining. I was particularly amused by his comment about how he has left his strict religious upbringing behind – "I don't mix with Christians now," he says, then recalls that "they always looked shifty."

Golden Girl (15:05)

Caroline Munro recalls landing her role as Margiana in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad through her connection with the film's screenwriter, Brian Clemens, with whom she was working on Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter, and her experience working on the film itself. She enthusiastically praises her fellow performers (she was clearly bewitched by John Philip Law, whom she describes as "beautiful"), reveals that they had a dialect coach to help with the Middle-Eastern accents, and outlines how the Kali combat sequence was blocked and rehearsed.

The Harryhausen Legacy (25:32)

A virtual Who's Who of visual effects artists – including Bob Burns, Phil Tippett, Ken Ralston, John Dykstra, Dennis Muren, Rick Baker and many more – are joined by directors John Landis, Joe Dante and Frank Darabont and legendary Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forrest J. Ackermann in a tribute to the extraordinary influence Harryhausen had on them and their peers. Almost all seem to have been inspired to enter the business after watching the Cyclops scene in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, and there are appreciations galore of Harryhausen's work and what continues to make it so special today. I was personally thrilled to hear Blade and Hellboy effects supervisor, Kevin Kutchaver, cite Talos slowly turning his head in Jason and the Argonauts as one of those moments that everyone remembers. Damned straight.

Super 8 Versions (29:07)

Once again, four sequences from the film on 8mm in a mixture of colour and monochrome, sound and silent.

Isolated Score

While it may not quite hit the "oh wow!" heights of Bernard Herrmann's superb score for The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, Miklos Rosza's musical accompaniment for The Golden Voyage of Sinbad is still thrilling and lively enough to make you want to jump aboard a ship and set sail for mysterious lands, and it sounds great here. As ever you'll have to know where the music falls to avoid sitting in silence for extended periods.

Theatrical Trailer (2:47)

A fast-cut and slightly trippy trailer with a deadly serious narrator. Just about every creature and major action scene is given brief representation.

Image Gallery

A manually advanced gallery of production stills, concept artwork, behind-the-scenes photos and other promotional material. There are loads to see here – I counted 148 slides, and many of those contain more than one image, all in crisp HD.

SINBAD AND THE EYE OF THE TIGER

The Guardian Interview with Ray Harryhausen (85:28)

Another audio interview whose content more than compensates for its occasionally distracting technical issues, this interview with Harryhausen by film writer and critic Philip Strick was conducted shortly after Clash of the Titans had opened in London. By this point in his career, Harryhausen was talking openly about his once secretive working methods, and does so in some detail here, and while some of this is duplicated elsewhere in this set, it's still all of considerable interest. Understandably, perhaps, there is a good deal of focus on Clash of the Titans, models from which Harryhausen has brought with him and talks about, sometimes in a way that makes you wish this had been captured on video as well. Great stuff, nonetheless, and once again it runs as a commentary track to the film to avoid plasma screen burn-in. Thank you.

The Princess Diaries (11:38)

The still beguiling Jane Seymour recalls landing the part of Princess Farah, how half of her role was given to Dione when Taryn Power came on board, and although she remembers it as a fun shoot, she has a few stories about how tough it also was at times. She talks about the problems caused by her braided hair, how Harryhausen was secretive about his working methods, and how she became typecast in ethnic roles in the UK, partly as a result of her work here. She also admits to not being a fan of the film when she first saw it, but now appreciates its influence on the next generation of filmmakers.

Ray Harryhausen Interviewed by John Landis (11:52)

Director and hyper-enthusiastic Harryhausen fan John Landis chats with the man himself about Jason and the Argonauts, which is clearly a Landis favourite. Harryhausen explains the technique of stop-motion animation, recalls what for him were the most challenging scenes to create, and Landis salutes the amount of personality that Harryhausen invests in his creations.

The Harryhausen Chronicles (57:56)

A comprehensive 1997 trip through Ray Harryhausen's career, narrated by Leonard Nimoy and with plenty of clips from the films under discussion. Of particular interest are the extracts from Harryhausen's early work with dinosaur models and his fairy tales for children, and even includes footage from unfinished work. Harryhausen himself is interviewed, as are his regular working partner Charles H. Schneer and James and the Giant Peach director Henry Selick, special effects supervisor Dennis Muren, and that Star Wars fellow, George Lucas. If you're somehow new to Harryhausen's work, this is a great place to start.

Isolated Score

A chance to catch Roy Budd's music score without the dialogue and effects if you can be patient during the silent sequences between. There is a lot of music in the film, however, and it's a typically fine score.

Theatrical Trailer (2:13)

Not the slickest or the most seductive trailer in this set, this was made at a time when those charged with providing the narration for trailers sounded as though they were doing so under duress.

Image Gallery

Another impressive collection of production stills and posters.

Booklet

This is one of those times, like the literary extras that have accompanied some of Arrow's prestige box sets, where the word ‘booklet' fails to justify what you actually get, which in this case is 78 pages of entertaining and knowledgeable reading material relating to all three films. You want details? All right, then. Following an opening quote from Guillermo del Toro and the credits for the first film, we are treated to the first of three excellent essays by Michael Brooke on the films and their gestation, one that concludes with the news that The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was one of the first films that he saw at the cinema, which prompted me to turn 13 separate shades of green in envy. This is followed by The 7th Voyage of Sinbad: An Oral History, in which Jeff Billington has compiled extracts from a range of interviews with the film's key personnel (including Harryhausen, Schneer, director Nathan Duran and lead actor Kerwin Matthews), to explore the genesis and making of the film in fascinating detail. Happily, it's the same story for all three films, with the credits for each followed by a detailed Michael Brooke essay and Jeff Billington's An Oral History compilation of interview clips. Following these, we have an essay with the intriguing title, Sinbad Goes to Mars, in which Billington has again compiled extracts from interviews with Ray Harryhausen, Charles H. Schneer and screenwriter Kenneth Kolb in which they discuss a proposed sequel to Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger that was looking to cash in on the success of Star Wars by adding a science fiction twist to the tale. Rounding things off is another short compilation of interview snippets exploring the Dynamation process, which again was edited by Mr. Billington. There's not a wasted word anywhere in this terrific read, and it's liberally illustrated with film stills, behind-the-scenes photos, posters and conceptual artwork.

That I'm over a week late with this review has surprised no-one close to me, not just because of continuing difficulties resulting from my day job and my home situation, but because my love of Harryhausen films forbade me from just knocking off a couple of paragraphs for each title and adding a quick summary of the special features, which alone took me almost a week to watch and review. Indicator have delivered some superb releases since their relatively recent arrival on the UK home entertainment scene, but this has to be their most glorious achievement to date. Three terrific movies, all handsomely transferred from top-notch restorations, and enough quality special features to keep you busy until this fine distributor's next set of releases arrive, and probably beyond. I genuinely can't praise this release highly enough, and given that it's limited to a run of just 6,000 copies, I'd grab one as fast as you can scrabble the cash together. As close to a definitive release of all three films as you could hope for. Highly recommended, and then some.

|