|

More than once I’ve noted that the first hook of a film is often the intrigue that even the briefest summary of its plot inspires. So with that in mind, try this one for the 1965 Japanese drama, A Story Written with Water (Mizu de kakareta monogatari):

A twenty-something office worker is having reservations about his upcoming marriage.

There you go. I’ll just bet that has you rushing out to buy this Radiance Blu-ray. As it happens, you should, as there’s much more to the film than that skeletal narrative description might suggest, just as there would be in any real-world equivalent (the disc itself is also seriously impressive, but I’ll get to why in the technical specs and special features below). That it was based on a novel – by popular Japanese author Ishizaka Yōjirō, no less – should not theoretically come as a surprise, as this is just the sort of tale that the written word tends to be more adept than film at portraying with any level of sophistication. Yet in the hands of director Yoshida Yoshishige – aka Yoshida Kijū – working from a screenplay by himself in collaboration with Ishidō Toshirō and Kora Rumiko, it feels like a story that was designed for cinematic telling from the ground up. Before I expand on the above, however, I should note that doing so in any meaningful way will lead me into what could be considered spoiler territory, so if you’re new to the film and have read little about it, feel free to skip to the penultimate paragraph of this review or click here to do so automatically. For those who stay with me, I’ll initially be keeping spoilers to a minimum, and will give a second warning before discussing the more revelatory issues.

The film opens in a manner that establishes characters and situational information with deft economy whilst dropping small pointers to a backstory that will become clearer over time. As the shutters close at the Ueda Bank, the many suited employees continue with the administrative work of the day. When one of them, Shizuo (Irikawa Yasunori), opens the top drawer of his desk, he discovers an envelope that we know from his reaction he did not place there himself. Inside is an unsigned, hand-written note with the intrusive question, “Shizuo, is Yumiko really a virgin?” With not an audible word spoken, we’ve been told the names of the lead character and his girlfriend, and that their relationship is possibly the subject of gossip or jealously on the part of at least one of Shizuo’s co-workers. From the way Shizuo subtly scans the busy and expansive office, he clearly doesn’t know who the author of the note might be, and it has clearly given him pause for contemplative thought.

When Shizuo leaves work, a woman that we can assume is Yumiko (Asaoka Ruriko) is waiting to pick him up in her car. As Shizuo approaches he is surprised to see a man we soon discover is Yumiko’s father Denzo (Yamagata Isao) in the rear seat, having cadged a lift from his daughter. In the conversation that follows, it is revealed that a man named Yamazaki – later identified as Shizuo’s immediate boss – has proposed to Shizuo’s mother, whom we can thus assume from this is either a widow or a divorcee. When Yumiko states that a woman in her 50s is still desirable these days, Denzo scoffs and retorts, “How can you talk such rubbish with a straight face?” Yumiko responds by suggesting that her father might be a little jealous of Yamazaki-san. Prophetic words, as it turns out.

When they drop Denzo off, Shizuo wonders who lives at the house he is heading towards. “Just some old lady,” Yumiko responds, but her expression suggests she may know more than she’s letting on. We then follow Denzo as he makes his way through the spacious garden of the abode to a building in which he is able to secretly meet with a woman, who turns out to be Shizuo’s mother, Shizuka (Okada Mariko). It emerges that the two had a clandestine affair ten years earlier, one that Denzo is now keen to revive, something Shizuko remains uncertain about, despite having agreed to meet him in secret. It’s also here that we learn for the first time that Shizuo and Yumiko are soon to be married, information that we once again first deduce from what is inferred rather than openly stated. From the moment we first meet her, there’s a melancholia to Shizuka that is directly reflected in Yoshida’s deft direction, as the camera peers down at the uneasy Shizuka’s neck, almost as if she feels embarrassed to face us, then drifts away from her hands and she withdraws from Denzo’s touch to glide across the texture of the tatami matting to the discordant notes of Ichiyanagi Toshi’s unsettling, almost avant-garde score. On a first viewing, this sequence is oddly discomforting, but second time around it takes on a whole new meaning, a trait it shares with many of many of the first-half scenes.

We then return to Shizuo and Yumiko as the latter breaks with pre-marital protocol by driving them to an onsen ryokan,* and as Shizuo contemplatively soaks in the communal bath, the camera swoops up and around the room and takes us back to a visit he made with his parents to this very same bathhouse as a child during the war. In the first of several such flashbacks we get to see how close Shizuo was to his mother from an early age, but also get our first glimpse of the cause of Shizuka’s widowhood when Shizou’s father Takao (Kishida Mori) suddenly chokes and starts coughing up blood. It’s in these flashbacks to Shizuo’s childhood that the seeds of his later uncertainty about his impending marriage are shown to have been sown, and which continue to impact him mental state even after he and Yumiko are married.

It's here that I have to issue that second spoiler warning, and those looking to go into the film for the first without foreknowledge of its central theme may wish to skip ahead to the penultimate paragraph or click here to do so automatically.

Before I proceed, it’s worth remembering that A Story Written with Water was made in 1965, and although Japanese filmmakers were working under different rules to those constraining their western counterparts, Yoshida still approaches the morally tricky subject at the film’s core with an impressive level of restraint and sly suggestion. And when I say morally tricky subject I mean it – almost 60 years later, this remains a touchy area for cinematic exploration, and for some will still be a taboo that has no place in film storytelling. Regular visitors to this site will be unsurprised to learn that I am not one of those people.

If you’ve made it this far then there’s a chance that you’ll have guessed that the issue I have so far been dancing around relates to the relationship between Shizuo and his mother, the suggestion being that it may be or have been an incestuous one. Yet while Yoshida’s does gently steer us towards this interpretation, the deliberately inexplicit nature of his approach allows for alternative readings, raising questions that linger even after the film has come to a close. Have Shizuo and Shizuka actually had a sexual relationship, or did they are they struggling with incestual desires that they have refrained from acting upon? Alternatively, is Shizuo just an over-protective mother’s boy, a young man so devoted to the widowed Shizuka that the prospect of finally having to leave the nest troubles and even potentially terrifies him? A case can certainly be made for the latter, notably late in the story when Shizuo pleads with Shizuka not to see Denzo again and confesses to her, “I was afraid to get married, in case something happened to you while I wasn’t around. I couldn’t bear the thought.”

Yet the small but significant signs that both have had a sexual relationship or have had incestuous desires are peppered throughout the film, moments that are often innocuous in isolation but collectively making an inferred case for the prosecution. The indicators are varied: the young Shizuo teased by his friends, who comment on his mother’s beauty and ask him if he still sleeps with her; Shizuo’s admission to Shizuka that he’s thinking of cancelling the wedding because “it just feels wrong”; the lingering look that passes between the two as Shizuo pauses on the stairway on his way to bed the same evening; his claim to the geisha (Yumi Keiko) that Denzo has set him up with that “sex and marriage don’t always mix very well”; his lack of sexual desire for Yumiko even at her most amorous; a grim late film proposal that he makes to Shizuka that suggests they are both harbouring a shared dark secret. Repeatedly, the film draws a line between Shizuo and Shizuka when it comes to their physical engagement with their respective partners, with the overture to a sexual encounter between Yumiko and Shizuo switching to Denzo simultaneously kissing and fondling Shizuka as she only tentatively responds or stares distractedly into space.

The nearest the film comes to an explicit suggestion comes during an accident-induced dream, during which Shizuo lowers himself onto a bed on which Yumiko is provocatively lying and moves to tenderly kiss her, only to have his wife transform into his mother, an image that Dhizuo responds to with alarm. But once again, is this a manifestation of the guilt he feels for sleeping with Shizuka or a Freudian desire that he has never acted upon? The clues are all there and remain inconclusive, being ultimately left to the viewer to make up their own mind. One point on which there appears to be no doubt is that Shizuo was sexually abused as a child, not by his mother but her friend Misako (Kayo Kimiko), an incident that occurs when Shizuka asks her to look after the house while she nips out to the shops. Although the film flips the paedophile stereotype by making the abuser female, her smiling request to Shizuo that he not tell his mother about this will have a familiar ring, and Shizuo’s cold refusal to respond when she enters his room, puts her arm around his shoulder and cheerfully tells him about her upcoming marriage suggests this is far from the first time he has been molested by her.

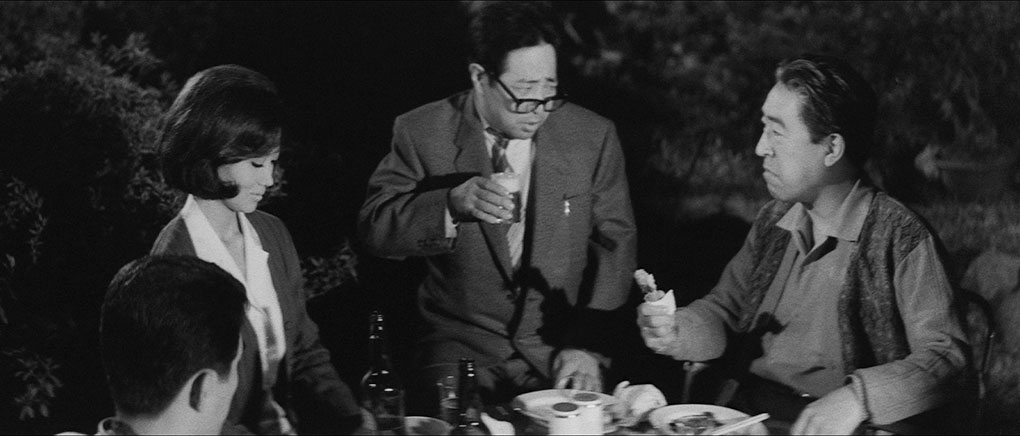

I’ll be honest and admit that I never quite worked out what the workplace dynamic was between Shizuo and Denzo. The request made by Yumiko at a family garden party to her father to help Shizuo’s immediate boss Yamazaki seems to indicate Denzo holds a top position in the Ueda Bank. Yet when Shizuo unexpectedly hands in his notice later, Yamazaki assumes he is leaving to work with Denzo at “the department store,” which suggests that he manages a different company altogether. Either way, Shizuo’s relationship with him is a complicated one. The polite deference that he shows to a man who is far higher up the business ladder than himself masks a deeply rooted dislike of the man, one fired by the knowledge that Denzo was sleeping with his mother back when his father was dying in hospital. Of course, if you accept that Shizuo and Shizuka were incestuously involved, you could chalk this resentment up to simple jealousy, yet when Shizuo later asks mother to stop seeing Denzo and consider marrying the lovelorn Yamazaki, it becomes clear that he’s not troubled by the idea of his mother dating again, but the fact that she’s sleeping with Denzo. His resentment bubbles over when he confronts Denzo directly about the timeline of his affair with Shizuka, raising a morally troubling question that so angers Denzo that he crashes the car in which the two are travelling. The accident and its aftermath are prime examples of how thoughtfully and intricately various scenes are connected, with the crash itself foreshadowing a later event and landing Shizuo in hospital, where his needs are tenderly dealt with by Shizuka in a direct reflection of the way she cared for her terminally ill husband. Read what you like into the fact that when they then turn to look at the troubled Yumiko, it plays like a mirror-image rerun of the time Shizuka and Tako did likewise to the young Shizuo after sharing a loving kiss while the latter was dying in what could almost be the same hospital bed. A Story Written with Water is one of the rare, special films about which I feel I could continue writing until my fingertips were worn raw, and believe me, I‘ve only scratched the surface in my scribblings above. Yoshida’s direction is impeccable throughout, often invisible but with the occasional, always purposeful flourish that is suggestive and meaningful in a manner unique to cinema as a medium of artistic expression. The economy of his storytelling is also admirable, bypassing events that would normally be the basis for showcase scenes. Thus, despite 50 minutes of uncertainty about whether it will even take place, we see nothing of Shizuo and Yumiko’s wedding, being clued into the fact that it has just taken place by a roadside photo taken by Yumiko and Shizuka’s sadness at her son’s departure. Later, the news that Yumiko has reached the end of her tether and moved out of their apartment through is almost casually dropped as part of a conversation between Shizuo and Denzo. The performances are pitch-perfect, with Okada Mariko in particular expressing so much through a look or her posture that the spoken word almost becomes a secondary means of communication, and Ichiyanagi Toshi’s unsettling, borderline experimental score and Suzuki Tatsuo’s monochrome scope cinematography are key to the film’s consistently disquieting tone. As for that enigmatic title, all I will say is that water plays a subtly relevant role throughout, in a manner that only really resonates on a second viewing.

If you’re looking for a cheerful tale you’ve come to the wrong film, but if it’s a bold, discomforting, precisely structured and beautifully handled one that questions the values of the traditional family unit and the then dominant societal patriarchy you’re after, then A Story Written with Water is definitely for you. There are so many moments throughout this remarkable film that I was captivated by and could talk about at length, but there’s one in particular that really struck on my first viewing and has had me pondering endlessly since. It occurs when Shizuo visits his mother just before his wedding and she presents him with a parcel containing his essays, drawings and diaries from his schooldays to give to Yumiko once they are married. On top of them is a small box, which Shizuka almost sheepishly reveals contains Shizuo’s umbilical cord. Far from being jolted or even repulsed by this news, a fascinated Shizuo opens the box, and in a question that neatly combines biology with philosophy and the film’s central themes, asks his mother, “Is this part of your body, or part of mine?”

I don’t know exactly who was responsible for the restoration sourced for this region B encoded Blu-ray but they’ve done an amazing job, as have Radiance with this genuinely excellent 1080p transfer. There are a couple of dark night-time scenes where almost all detail is lost in the gloom, but I have the sense that this was an intentional move on the part of director Yoshida and cinematographer Suzuki Tatsuo, as was the enhanced brightness of the post-crash dream sequence. Otherwise, the image quality is divine, with pitch-perfect contrast, a generous tonal range, and very crisply defined detail throughout – on close-ups, you can often see the skin pores on actors faces. Framed in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, image is also clean of dust and only oaccsionally displays very faint traces of wear.

The original Japanese language soundtrack is presented here as Linear PCM 2.0 mono, and while there are the expected tonal range restrictions, the dialogue and especially Ichiyanagi Toshi’s score are both clear and there are no obvious signs of damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default.

Yoshida Kijū (2:46)

Filmed in Tōkyō in 2008, this introduction to the film by director Yoshida Yoshishige Kijū directly addresses the film’s central themes, and thus, in common with all of the special features here, this should ideally not be watched until after you’ve seen the film itself. He does talk briefly about wanting to address the patriarchy and male chauvinism of Japan of the day, and reveals that he saw the film almost as a Greek tragedy. As we lost Yoshida in 2022 at the age of 89, this is a most valuable and welcome grab.

Okada Mariko (11:33)

Lead actress Okada Mariko, who plays Shizuka in the film, recalls wanting to become a director herself until she ended up marrying Yoshida Kijū, and discusses their decision to break with the Shochiku studio and start making films independently, and how this led to them making A Story Written with Water. She reveals that Yoshida didn’t tell her how to play her character and let her portray Shizuka as she saw fit, admits that the first day of shooting is always the scariest, and assures us making movies is her whole life. A hugely welcome inclusion.

Jennifer Coates (21:42)

Author and scholar Jennifer Coates impressed me from the off by using the Japanese convention of family name first when referring to the Japanese actors and filmmakers, a convention I always respectfully follow in my reviews of Japanese films, this one included. She notes up front that director Yoshida wanted the spectator to have some ownership of his films, to which she responds by examining the themes of A Story Written with Water, as well as discussing key aspects in their historical context. She also offers an intriguing reading of the title, one that would not otherwise have occurred to me.

Trailer (3:25)

Wow. Given that the prime purpose of this original Japanese trailer was to sell the film, its makers have taken a real risk by going full arthouse with its imagery and the more experimental elements of Ichiyanagi Toshi’s score, as well as adding a few captioned poetic philosophical musings. There are also a couple of whopping spoilers (including one that even I have not been explicit about), so definitely steer clear of this until after you’ve seen the film.

Also included is a Limited Edition Booklet featuring new writing by scholar and author Alexander Jacoby, but this was not available for review.

Despite my love of Japan and Japanese cinema, the constraints on my free time and the sheer number of discs sent to us for coverage over the years means that A Story Written with Water was my introduction to the cinema of Yoshida Kijū, despite my so far unsuccessful efforts to catch his acclaimed and intriguingly titled Eros + Massacre (Erosu purasu gyakusatsu, 1969), and frankly, I was blown away. This is the polar opposite of sensationalist filmmaking, instead tackling a potentially difficult issue with remarkable reserve, subtly suggesting what others would loudly proclaim. The result is a beautifully handled film with impeccable performances, one that while admittedly bereft of cheer, almost immediately drew me back for a revealing second viewing and has stayed with me since. The restoration and transfer of the Radiance Blu-ray is superb and the special features are all spot on. Not for everyone, I know, but this still gets my highest recommendation. Note, though, that this is a late review of a Limited Edition Blu-ray that appears to be selling fast, so make sure to grab it while you can.

The Japanese convention of family name first is used for Japanese names throughout this review.

|