"The essence of dramatic form is to let an idea come over people without

it being plainly stated. When you say something directly, it's simply not

as potent as it is when you allow people to discover it for themselves." |

Director, Stanley Kubrick |

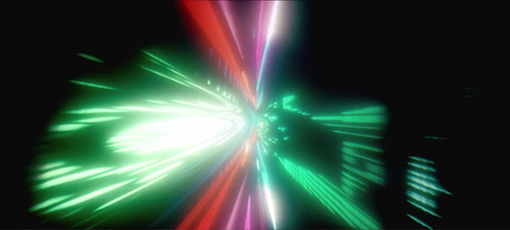

What hasn't been written about 2001: A Space Odyssey? That it was a sophisticated cover for a faked moon landing? Been there, done that. That it compelled those who saw it at an impressionable age to seek a career in film? That it certainly did; your humble narrator for one. It's probably been written somewhere that an anagram of its title is "Decoy!" say 2001 apes. There's a self-fulfilling sentence for you. I promise to try and not to go over a lot of old ground if you are already a 2001 aficionado. What I'm more interested in is this remarkable film's legacy and influence and I'd like to put to bed some odd canards that have popped up and stayed popped up when they should have been blown out of the debris airlock a long time ago. There is a common consensus about this film that it was rescued from box office oblivion by the presence of young men and women who partook of recreational drugs and got off on the extraordinary imagery not least the multi-coloured, swirling star gate that takes Bowman the hapless astronaut to an alien environment. Douglas Trumbull, one of the effects supervisors and creator of the star gate imagery says as much in one of the documentaries included in this release. Now it may be true that there were faltering steps but other sources report that 2001 was a hit from the word go (celluloid releases were widely staggered in the late 60s and under-performing movies were given a hell of a lot more breathing room to prove themselves than they are now). Critics like John Russell Taylor of The Times had at first dismissed the film and then significantly took a friend to a second viewing and made a startling discovery of his own. If you will indulge me, let's drip-feed a few choice quotations to get to the point. Taylor starts with a frank admission;

"There are times in the cinema these days when I begin to feel that perhaps I have a faint inkling of how the mammoth felt when the ice began to melt. It struck me with peculiar force this week when I took a friend to see 2001: A Space Odyssey."

Much like the effect of the mysterious alien monolith in the movie itself, the film 2001 has influenced the evolution of cinema in countless ways. Forty-six years after it was made, it's still the benchmark of almost flawless effects work. It is close to inconceivable to imagine the amount of labour that went into the making of 2001. In the last few weeks I have re-read "The Making of..." by Jerome Agel, The BFI Classic on the movie, Cinefantastique and Cinefex magazines' retrospectives on the film and the relevant sections of the enormous tome that is the Stanley Kubrick Archives. The wealth of detail available is staggering and it's as much a surprise to learn about all the ideas that were tried and failed to make the cut than it is to find detail on the extraordinary shots and sequences that actually make up this masterpiece. Did you know that Kubrick had a Perspex monolith made with the intention of it being completely transparent? This object, a real world item not some computer generated phantom, took a month to cool down (a month!) because if it cooled any faster it would shatter. It was rejected for not being transparent enough. And yet, the actual monolith then turned out to be completely black and in the real world as mundane as a piece of painted wood and painstakingly kept scrupulously clean. This is as good a metaphor for Kubrick's thought processes as any. He was open to a vast spectrum of ideas and 2001 is much more a collaborative effort with Kubrick calling the shots than it was a one-man operation. Kubrick admitted that while he didn't know what he wanted precisely, he knew what he didn't want. This meant trial and error on an unimaginable scale. No filmmaker today would be afforded that luxury and yet some still believe that creativity flows on tap and in strictly measurable quantities. If there are gods I believe in, it's the movie gods and they blessed Stanley Kubrick for most of his career and in the case of 2001, even they were awestruck. Kubrick was playing in their celestial sand pit after all.

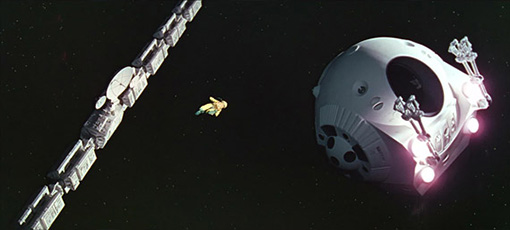

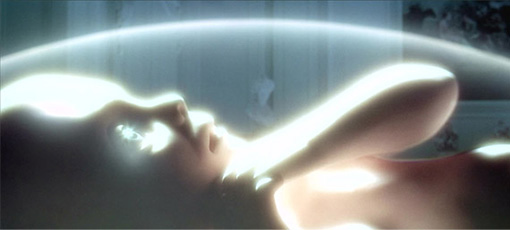

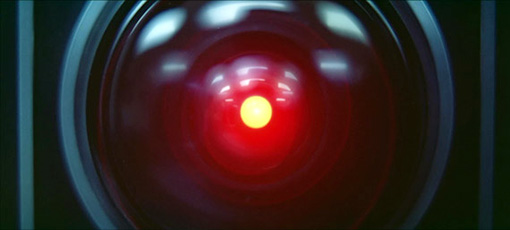

For those unfamiliar with the film, a brief synopsis is necessary but be aware. This is like trying to describe the effects of music or the taste of the garlic and rosemary soaked fat clinging to a lamb chop. Some things you just have to experience first hand. If you've not seen this movie, it really is worth seeking it out on the biggest screen you can find. While I'm obviously recommending this Blu-ray, this is a Cinerama production shot on 65mm film and I urge you to attend a theatrical showing that the BFI are planning later this year. I hope they have a pristine print. Something tells me it may be a digital projection in which case I hope the source from which the media file is scanned is pristine... History tells us that the year 2001 will be remembered more for a faith atrocity than a space odyssey but despite space exploration grinding to a halt after the last Apollo mission in December 1972, the movie reminds us that we are creatures of relentless enquiry and insatiable curiosity. There are significant practical (and depressingly economic) hurdles but we'll get out there eventually. There are four distinct sections in the film. The Dawn of Man features our ancient ape-like ancestors getting a little outside help on the evolutionary road. Contact with a black, alien monolith kick starts our use of tools. Via the most famous cut in film history – bone to spaceship (which is actually an orbiting atomic bomb but the movie doesn't tell us this) – we travel to the moon with Heyward Floyd to find another similar artifact, a monolith that now emits a pulse towards Jupiter. The Jupiter Mission Eighteen Months Later section reveals the giant space ship Discovery approaching its rendezvous with... who knows? But HAL, the on board computer is acting up playing merry hell with the crew. Jupiter And Beyond The Infinite takes a lone astronaut on a journey we will never forget...

2001 doesn't boast a complex narrative. The story is very simple. Dramatically there's a deliberate flatness to some of the performances, a commonplace aspect that Kubrick must have felt justified itself given the nature of the experience he was concocting. This is reflected in the less than compelling dialogue (the sandwich chat is priceless in its mundanity; "Anybody hungry?" "What have you got?" "You name it." "What's that, chicken?" "Something like that. Tastes the same anyway." "Got any ham?" I kept wanting to shout, "Look out of the fecking window! You're on the moon!") Concentrate on these elements and you'd be missing the point. These aspects are like subtle pound weights that anchor the dazzling images and keep the whole spectacle from floating away from our human recognition and reception. It is a movie experience of ideas and the most thrilling aspect? They're all yours. Kubrick just gave us the playground and the toys. What joys or frustrations we glean from them is totally up to us. And the catalysts on offer lead to the big questions; our place in the universe, sentient technology, philosophy, evolution, all in the premier league of human consciousness. 2001 is the bodhisattva of movies, a master there to help the student attain nirvana on his or her own. I had a rather special evening after a screening of 2001 because the girl in the row in front of me asked her friend "Well, what was all that about?" – a better opening line to a wonderful conversation I could not imagine.

Trial and error on a movie set is vastly consuming of effort, money, time and materials. Kubrick's talented technicians had to create ways of shooting certain effects from scratch. I cannot imagine what wonderful stuff fell by the wayside. The shooting ratio ended up at 200:1 (I know, lovely, isn't it?), which in these digital days is chicken feed, but for a Cinerama epic, that was five hundred hours (almost twenty one days of continuous viewing) of very expensive film shot for a two and a half hour picture lock. Aside from some basic narrative components of the film, Kubrick was improvising a great deal as he went along and all hail MGM's brass for having the balls to let him. Originally the film was to have substantial voiceovers (an aspect that would have killed its mystery and allure) and there had been plans to put a monitor on the monolith, for this wonderful object to be a literal visual aid. That would have been laughed off the screen. It's Teletubby time, "...Again! Again!" And they really wanted and intended to feature extraterrestrials before Kubrick put his hands up defeated by simple logic. How do you show the unimaginable? He wisely left his extraterrestrials off screen and experimented very effectively with sound instead. The E.T. sketches in the Archive are extremely interesting not least because one of them – featuring a tall humanoid creature – is the spitting image of the first E.T. off the mothership in Spielberg's Close Encounters, the tall guy who all but disappears in a cut or two. We'll get to Spielberg a little later but here's another extract from Russell Taylor's second review of 2001...

"I admired the elaboration of the technical scenes showing the arrival of the spaceship at the space station and so on, but still tended to feel that they were overlong in reaction to the film as a whole, as though Stanley Kubrick had had so much fun devising them that he failed, when editing the film, to appreciate that they would be considerably less interesting to an audience than they were to him.

Ah, but that was where I was wrong. In the audience when I saw the film again, there were lots of children, especially boys, under 15, generally with fathers and sometimes with mothers in tow."

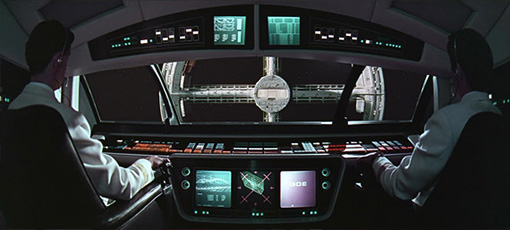

I was one of those children. I remember being spellbound by the sights and sounds (and silences) of 2001. Here were impossible images on screen. Moon bases with little areas in which people toiled. Accompanied by the famous Blue Danube waltz of old, giant Ferris wheel space stations whirled with such grace and realism; it was hard not to be utterly seduced. There were interior cockpits with computer screens and perfect views without a blue matte line in sight. As much as I have decried perfection on this site for lacking the human element, I bow to the level of superior craft in evidence on this film. Kubrick managed to take perfection to a level so far above standard that it created its own heady atmosphere and personally speaking, so deeply was it inhaled. There are several 'mistakes' in 2001 but they were either beyond Kubrick's budget to fix or judged to be included for the fun of it. Yes, the words 'Kubrick' and 'fun' are in the same sentence. Do not be alarmed. This is not a drill. For the record, here they are (or the ones I have picked up on); the eyes of the leopard shining back at you in the Dawn Of Man sequence caused by the front projection and the architecture of a feline's eye – apparently Kubrick loved the effect and so in it stayed; the food in the straw being sucked up by Heyward Floyd that drops down which in Zero G would have remained where it was (this is an easy fix, FX wise so I have to assume Kubrick meant it as an intentional 'error'); the moon shuttle and moon pod both kick up dust which shouldn't behave as if there was normal gravity which it does. The shuttle travels left to right then right to left and then left to right again which goes against traditional editing craft but hey, in a movie with arguably the most famous cut of all (directly preceded by one of the most ungainly), who am I to question conventional direction in a sequence? Ray Lovejoy edited 2001 but I suspect that cut was a Kubrick intention – I'm all too happy to be disabused of that. For some reason, the title The Dawn Of Man is in the uppercase Albertus typeface (in vogue in the late 60s. It was the default font of the Village in The Prisoner) while all others are in a simpler, narrow font. It bugs me why this is the case. If you're interested, all the continuity errors are listed on 2001's IMDb page but hey, picking holes in a movie this good is not as satisfying as it might seem to be. It's a little like criticising Johann Sebastian Bach for using paper from unsustainable forests to write his musical notation on when you really should be fainting at, praying to or simply surrendering to the utter perfection of his music. What music, what perfection.

This brings us to the original bespoke score. Alex North was a brilliant composer who'd worked with Kubrick on Spartacus. Kubrick hired North to score 2001 and he duly and dutifully delivered a score based very much on the temp track laid by Ray Lovejoy at the time. North, like all composers, dreaded it when directors fall in love with their temp tracks (music laid to give everyone an idea of the mood and emotion intended by the scene). He was right to dread it. Kubrick dismissed North's superlative score and in doing so, embraced his own temp track. It has subsequently become one of the most famous in all cinema. Children today hear Strauss' Blue Danube and announce "It's the space music!" according to Kubrick's longstanding friend Jan Harlan. The Ligeti and Khachaturian cues fit 2001 like a glove fitted by a master glovesman with a PhD in Gloveology. You cannot imagine some of Kubrick's images without these pieces of music. They are so fitting, so right, you almost pity North having to attempt to replicate them or their emotional effect. To his great credit, master composer and friend of North's, Jerry Goldsmith, recorded North's score for 2001 and it's a real head rush to imagine Kubrick's film with this version of the music knowing what was eventually decided upon had worked so well. North must have been crushed.

Non sequitur alert. Both Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg were brought up by Jewish parents. Apart from being virtuoso craftsmen I was trying to find anything that linked these two directors. That was a bit of a stretch, granted. Kubrick had no formal religious upbringing and lived his life with a burning curiosity and an open mind towards all matters spiritual, divine and extraterrestrial. Spielberg was mocked as a high-school student for his ethnicity but later aligned himself very squarely with Jewish concerns and as far as I can make out, he believes in a God or certainly a higher power within the constructs of his own religion. He has now allied himself with 'the oldest tribe in the world'. His belief in God may be, like politicians' beliefs, a sop to his maintenance of continued popularity. You can't make movies for the masses and not share the God delusion. I am saying nothing definitive here because I do not know these people but I do feel in my heart and head that Obama is an atheist but could never publically 'come out' for fear of losing grassroots' support. But that itch in the artist prompted by profound thoughts of creation and the divine has brought forth fruit, fruit as unforbidden as it can be, fruit shared and lovingly given away – in some cases to those who cannot appreciate the generosity.

In the last years of his life, Stanley Kubrick nurtured a relationship with Steven Spielberg. Both derived the considerable advantages of each other's acquaintance. Spielberg's relatively consistent commercial success impressed Kubrick to the point where I believe he asked him how it was done (as if Spielberg knew but then making resolutely reassuring films – even about the Holocaust – and having millions at his disposal for marketing and distribution probably greased those wheels). Spielberg said in an interview that he had to disconnect his FAX machine because its Kubrick-penned outpourings were keeping him and his wife up at night. A small price to pay, methinks. Allying himself with Kubrick and his reputation in the industry as one of the few truly 'great' filmmakers allowed Spielberg a sort of artistic cachet, a respect that cannot be earned, ironically, from millions of those dead presidents' faces looking out from their green paper homes. Spielberg is a giant commercially but he struggles to regard himself (or get the world to regard him) as a bonafide artist. I have no idea what Kubrick's A.I. would have turned out like but with Spielberg it was not a good fit at all. After seeing Bob Fosse's masterful All That Jazz, his Jaws star Roy Scheider asked his erstwhile director's opinion. "It won't make a cent. He dies at the end..." Scheider had to remind him that the artist's death was "...sort of the point." Spielberg's 'art' is his uncanny knack of making audience–pleasing films but his insistence on supplying an audience drama and thrills that he believes they want to see will always limit his standing in cinema history. Spielberg seems incapable of making hard narrative choices preferring always, even in the midst of horror and darkness to give his audience something to cling on to. Kubrick knows that sometimes it's important to set his audiences adrift. It's a crucial difference. Kubrick envied Spielberg's cash flow as much as Spielberg seemed to covet Kubrick's status as a full-blown artist. They are the heads and tails of the same rather wonderful directorial coin. In the most simplistic of metaphorical terms, Stanley was the man and Steven the child. And in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the man spoke to the child profoundly. As I said earlier, I was one of those children and from some research and received personal anecdotes (thank you Slarek), it seems as if I wasn't the only child who 'got it' while the adults floundered.

My father went in to 2001 expecting a Flash Gordony Star Wars. He came out befuddled. I came out of 2001 with my life's ambition decided. It is immensely odd to base one's whole life on the caprice of a ten-year-old but hey, when film loses its magic (and by god, the Bays of this world are trying their hardest to make that happen), I'll hang up my glasses and admit defeat. But while Kubrick was still working, film had its Michelangelo. Seeing the all too ordinary sequel 2010 starring a few of my favourite actors just underlined how wonderful Kubrick's original really was. And still is. Director Peter Hyams was stepping into enormous shoes. Even the details let him down (perhaps he simply couldn't afford to be a wannabe Kubrick): Sets were chipped and imperfect, there were visible wires, visible mattes and matte lines, sulphur particles in space on the surface of the Odyssey acting as if affected by gravity, cathode ray tube screens in place of the flat screens of the original and worst of all, the need to explain everything via Roy Scheider's voiceover to his wife and son. Stanley would have had none of the above. But then, if I've learned nothing else, there was only one Stanley Kubrick and his passing in 1999 closed the door on a standard in filmmaking that no digitally soaked epic has yet to come close to. I'm not saying we won't have our classics in the now and the future but we won't have any more Stanley Kubrick movies so let's cherish what we have even more. And for my money, 2001 is his true masterpiece.

A final revelatory word from Russell Taylor's considered second review of 2001... Remember that kid he was talking about?

He was, that is to say, not in the slightest worried by a nagging need to make connections, or to understand how one moment, one spectacular effort, fitted in with, led up to or led on from another. He was accepting it like, dare one say, an LSD trip, in which a succession of thrilling impressions are flashed on to a brain free of the trammels of rational thought. Nor can one put this down to his age and education: it is not, after all, a particularly childish way of seeing things. As any teacher will tell you, children tend on the whole, especially at that age, to be the most stuffily rationalistic of all, constantly demanding believable hows and whys.

No. It seems to me that what we have here, in a rather extreme form, is a whole new way of assimilating narrative.

Wow.

No, really. Wow.

And another wow! Why?

Because this is exactly what is happening in our current culture without the benefit of a Stanley Kubrick movie to introduce us to it.

The practice of teenage over-screenage has seeped into our lives, tablet by smartphone, and movies are now being consumed in vastly different ways. Perhaps there's a great filmmaker out there who will make the definitive zeitgeist defining work that will allow that very different experience of seeing a film coalesce into something new, something exciting. Not sure I'd be able to appreciate it though.

Now I know what it feels like to be a mammoth when the ice starts melting...

Here we go... First thing that strikes you is the lack of a home screen. The movie auto-plays immediately (it's a nice touch to include the music played while the curtains are closed at the start and at the end. Even the intermission – well named for 2001 – gets included). The menu choices are activated while the movie is playing which is fine but it just feels odd not to have a home screen to return to.

2001 is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.2:1 and as the pinnacle of the photochemical craft, it would be a shame to report that the print was anything less than pristine. I'm happy to say that it looks gorgeous with one tiny caveat that we'll get to in a moment. If you were really looking, you may find an odd hair or dust spot but you'd have to be really looking hard. Given the amount of white in the movie, it's a little miracle the print is this clean. Grain is more in evidence than any other so-called flaw but again, you'd have to be inches from the screen to be seriously affected by it. But there is a weird issue with a few shots and if anyone has an idea what this is, I'd be most interested to hear from you.

There are several shots in The Dawn of Man sequence (see one above) in which the sky is broken up by a kind of smearing tiled effect. When the camera moves, this smearing doesn't so it's been photographed and is not part of the actual negative or print. If it were, it would obviously stay in the same position in frame. On closer examination, you can see this smearing on the land parts of the picture too on both sides of frame. It is present on a significant number of shots in the whole Dawn Of Man sequence. We all know this sequence was shot with front projection so it has been suggested that the irregularities are caused by the uneven application of the 3M reflective material of the screen. If I accept this, I have to accept that so did Stanley Kubrick and that's where I'm having a major problem. Given the default perfection of the shots in this incredible film, it seems utterly impossible to me that Kubrick would have 'passed' these shots as they are presented here. Is there any way that this smearing was significantly reduced on projected prints so it was hardly noticeable? This is one mystery of 2001 that I would like someone to solve.

The audio on offer is extensive. In English you have the PCM rendered in Dolby Digital 5.1. To be faithful to the original final mix, I'm assuming that no re-mixing was done. You want to feel the sub rattle your bones while Bowman is going through the star gate? The sub-woofer gets a little work here but not at a frequency to have one's socks well and truly gusted away. This is a theatrical surround track mixed in 1968. The surround speakers feature mostly ambient sound while the sub woofer is underused and most of the mix emanates from the centre. It is a very good mix to be sure. I just would have liked to have been vibrated a bit more by the journey at the climax. No putting that sentence on any posters...

The Audio is also available as a Dolby Digital 5.1 mix dubbed into French, German, Italian and Spanish and there is a whole host of multi-lingual subtitles; English SDH, French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, German SDH, Cantonese, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Italian, Italian SDH, Korean, Norwegian and Swedish. I wonder why only English, German and Italian speakers get the luxury of the enhanced subtitle experience?

With the obvious exception of the audio elements, all Extra Features are 480p standard definition and with an aspect ratio of 16:9 unless otherwise stated.

Feature Length Commentary with Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood

It's hard to figure out if both actors are interacting (I suspect not) as there is no 'dialogue' between them, no awareness of each other's presence. I'm assuming they were recorded separately and whoever had the most interesting thing to say about the scene being shown at that moment was edited in. Gary Lockwood (let's not forget he was a famous astronaut to Star Trek fans too) is the more insightful in terms of his own character and his relationship with Kubrick. He said that Kubrick's curiosity coupled with his intellect made for a great director. That's a pretty good combination. I wouldn't go to Gary for natural history expertise. He called the tapirs at the start 'hyena type animals'. He got a lot of flack for announcing the movie a masterpiece to the press but has since been proved right. In expounding on what alien life might look like he cites two of the oddest examples; he says they may all look like "Rock Hudson... or Bela Lugosi." Warren Beatty at the premiere recognised the movie's brilliance by simply saying to Lockwood "You're lucky..." Smart man, that Beatty. Kubrick apparently hired Lockwood because "You can do a lot by not doing a lot." Fair enough.

If Lockwood is the frontiersman, his co-star Dullea is lighter and is, presumably unintentionally, centred on his own performance. This isn't a bad thing but you do get the sense his actor's ego is getting a vigorous massage. There's still plenty of really silly 'saying what's on screen' which is starting to drive me a little crazy. When we see the first still of Dullea in the star gate, the actor says (I kid thee not) "Hullo, that looked like a still!" His chatter over the Louis XVI hotel room alien zoo scene was an attempt to explain the rationale behind the idea. I found it a little by the numbers. He imparts lots of fascinating facts, no question but there is a sense that Dullea is far more centred on the essence of his own role. He has no compunction in informing us that Kubrick thought he was "...a wonderful, wonderful actor." But he does tell us that the person on the movie who did the tiniest amount of work but had the greatest effect in the overall was of course Douglas Rain, the voice of HAL, who spent nine hours recording his lines. And that old age make up? It took twelve hours to apply but it looked significantly better than his repeat appearance in the sequel. On the whole it's an informative and interesting commentary slightly tripped up by many descriptions of what we're looking at and a concentration on the role of the actor (that's hardly a surprise). Next time, liven things up and get the guys physically together.

2001: The Making of a Myth (43' 08")

James Cameron hosts a broad appreciation of 2001 from where Captain Kirk and the Gorn went mano a mano (Vasquez Rocks). What is it about that location and science fiction filmmakers? Everyone's on board including writer Arthur C. Clarke, Con Pederson, Douglas Trumbull and Brian Johnson (the effects maestros) and scientific advisor, Fred Ordway. It's nice to see UFO's Commander Straker himself, Ed Bishop, admitting that he and Kubrick were on different wavelengths and that his opinion of Kubrick's method was "excessive..." Hmm. Dan Richter, the mime artist who played the lead ape named 'Moonwatcher' talks about how they prepared for The Dawn Of Man sequence. Editor Ray Lovejoy waxes lyrical about the romance of real film editing, something he believes that computers cannot provide. I can fully sympathise. Extracts from A Look Behind The Future are used and in one dodgy moment, a shot of Kubrick directing remotely on the centrifuge set is cut in to appear as if it was in the editing room (a shot of the Discovery has been matted on to the screen Kubrick was looking at which originally comprised of a TV image of Lockwood in the centrifuge). I have to say that the filmmakers obviously had a problem clearing the rights to use the original score even over the clips from the actual movie. The electronic facsimiles are frankly embarrassing. In fact the gorgeous images are laid low (assassinated even) by the falseness of the music. I'm sure it's not the composer's fault but it just shows what the wrong music can do to an astounding image – utterly belittle it.

Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick: The Legacy of 2001 (21' 25")

Famous directors and craftspeople line up to acknowledge 2001's effect on their lives and careers. There's an unintentional bit of enormous arrogance from, of all people, George Lucas, who says in the introduction how inspirational the film was and that "...if he could do it, I could do it." Lucas is no Kubrick. That's accepted, isn't it? 2001 made science fiction respectable. There's a lovely dialogue exchange reported by Spielberg that Kubrick told him that he wanted to change 'the form' of cinema. Spielberg, correctly in my view, came back with "Didn't you already do that with 2001?" On a personal note, this Extra contains one of the only uses of the word 'awesome' that doesn't set my teeth on edge.

Vision of a Future Passed: The Prophecy of 2001 (21' 31")

With the same participants as Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick, we get a little more specific and start to look at 2001's legacy in terms of futuristic technology. It's quite startling to realise how much we take for granted in the year 2014. What glories Kubrick may have produced, with a Hubble Telescope? Kubrick had no way of knowing what our own planet looked like from space. There were some concerns that the surface of the moon might have been just dust ready to swallow any craft or astronaut unlucky enough to land on it. There is an interesting re-use of John Williams' score for JFK dotted all through this Extra. FX pioneer Richard Edlund makes the point of the advance of computer power but as this Extra was made just before the disc was released in 2007, there's something almost quaintly out of date about his remarks.

2001: A Space Odyssey – A Look Behind the Future 4:3 (23' 11")

This piece was aimed at America's advertisers or rather the introduction and coda were. The actual 'Look Behind The Future' is nestled in between. Look magazine's publisher Vernon Myers introduces the Saturn rocket and the Apollo missions and suggests a way of preparing the world's populace for the space age. Shot during the shooting of 2001, this lovely effort of prediction shows us 1966's version of a MacBook Pro – gorgeous! A typewriter in a briefcase with a phone attached. Brilliant. Kubrick's technical advisors are front and centre in this fascinating glimpse behind the scenes. The narrator tells us that the story starts on the moon... Uh... Maybe it did in 1966 but not anymore (let's not include the title shot). We get a look at the Discovery's centrifuge in action. We see Arthur C. Clarke in New York overseeing the making of the real LEM, the Lunar Excursion Module. Actor Kier Dullea grants an interview and the relentless sixties cheerful music dates the Extra like no other aspect.

What is Out There? (20' 42")

Starting with a long clip from the film (Heyward's taped message to the astronaut inside HAL's red mind space), this is Kier Dullea's show about the possibility of extraterrestrial life. A tiny niggle; Dullea sort of reads from a piece of paper on his knee and then looks up into camera. Surely a more professional way could have been found to help him along with his lines? The casual and continual looking down at notes makes the whole thing seem too stagey. When he's quoting it's entirely acceptable but not when he's presenting. The surprise in this Extra is the fact that Kubrick had originally planned to start the movie with a talking head prologue, a series of experts musing on the subject of extraterrestrials. Aren't we lucky he didn't go with that idea... Dullea intersperses his presentation with quotes from the scientists interviewed for 2001.

2001: FX and Early Conceptual Artwork (9' 28")

Douglas Trumbull takes us through the origin and application of a few FX shots. Kubrick's wife Christiane introduces some of what must have been a prodigious amount of artwork for the 'Infinite' section of the movie, surely the hardest scene to realise. Kubrick's direction to his artists was priceless. "Show me something that doesn't remind me of anything else in a colour that doesn't exist..." You have to love this man. There's artwork in here that suspiciously echoes the final gravity challenged rocks and boulders of Cameron's Avatar. I'm not suggesting anything here except for the odd coincidence. And that Cameron hosted the main documentary on this disc.

Look! Stanley Kubrick! (3' 15")

Kubrick's early photographic efforts are showcased here with a charming look at the still photographic start of a glittering career. Inventively cut to a jazz score Howard Moon would adore, this zips along showing off the young Kubrick's gift for composition and mood. What a vastly different world it was in the late 40s...

Audio Interview with Stanley Kubrick, 1966 (1 hour 16' 30")

Director Stanley Kubrick, with physicist Jeremy Bernstein, discusses his whole career ending on the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey in this 1966 audio interview. The fairly affable Kubrick is open and informative about his childhood, schooling and career, including some info on 2001. He reveals he was taught to play chess at 12 years old and when a young man in New York, played strangers for a quarter a game in Central Park. He said you could make a few dollars, enough to buy food. This revealing tidbit is loaded with subtext. Despite being 'Stanley Kubrick' he was all too aware of how much things cost. He couldn't have had too poor a childhood (his father was a doctor) but it is significant to me when someone reveals this kind of economic awareness. He states that learning to solve problems in photography gave him a basis of problem solving across all areas. It surprised me to find out that he didn't have good enough grades to go to higher education. This was less to do with his rampant idiocy (hmm) and more to do with two things; the first was that he only applied himself to stuff he was interested in and secondly in 1945, there was a huge influx of soldiers returning to their loved ones after the Second World War so competition was fierce. In trying to explain what he liked about collaborator Arthur C. Clarke, he gets so flowery he asks the interviewer to "...clean this up. It sounds like crap." As a Kubrick 101, this interview is just the ticket. Add it to the Playboy interview, which I'm sure you can find online (it's in the Archive and The Making Of...) and you have a comprehensive account of everything Kubrick has to say on the subject of 2001.

Theatrical Trailer (1' 51")

Richard Strauss' Also Sprach Zarathustra throttles up to full power and accompanies some of the more extraordinary images from the movie. This may sound very odd but there are spoiler shots in the trailer but only if you'd seen the film before. How's that for a piece of thinking right out of 2001's philosophy department? It's a little grubby but hey, it's an old trailer.

This is a cracking disc of one of the most influential and staggering films of all time. With that tiny caveat about the mysterious front projection smearing out of the way, you're not going to get a better transfer for our 2K HD TVs. I can't help but wonder how it might scrub up on a 4K screen. The 65mm negative (I hope) is being treated like gold in some armed guarded vault. Maybe I'll live long enough to see that too. But for now, this version of the film is more than enthusiastically recommended for fans and newbies alike.

|