|

I'm fond of titles like The Woman in the Window. They tell you nothing about the film's story or even its genre but instead give you one significant detail and invite you to speculate on its relevance and where it will lead. And The Woman in the Window has so many possibilities. It could easily, for instance, have been an alternative title for Suo Masayuki's delightful Shall we dansu?, whose main story kicks off when unhappy salaryman Sugiyama Shohei is captivated by a woman he sees standing at the window of a dance studio whilst on his way home from work by train. In Fritz Lang's riveting 1944 noir crime drama, it has a double meaning, being represented first by a portrait in a storefront window that catches the eye of college professor Richard Wanley, then later by the reflection in the very same window of the woman who modelled for the painting. This moment will prove significant not just for instigating the story that follows, but for reasons that cannot be discussed without delivering a howling plot spoiler. Be warned now, I have every intention of doing just that – a warning will be given before I do so, but to discuss what could be a major issue for anyone coming to this film for the first time, it really is unavoidable.

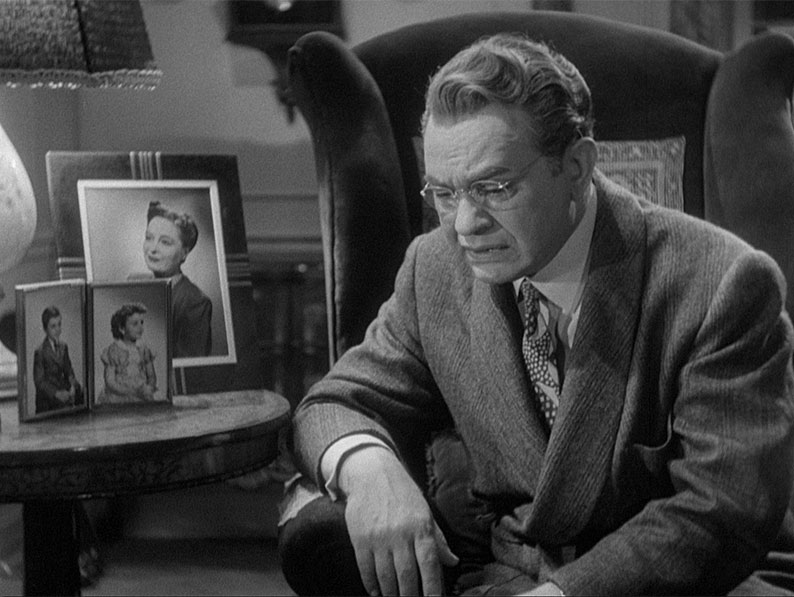

Wanley is played by Edward G. Robinson and it's a refreshing role for a man whose crumpled features and short stature saw him shoot to fame not as a romantic lead but as murderous mobster Rico Bandello in Mervyn LeRoy's 1931 gangster classic, Little Caesar. Here he's not a tough guy or even the hard-nosed investigator he has also played with aplomb, but a mild-mannered, middle-aged psychology professor with a wife and two children, and who regularly meets with two similarly aged friends at a local men's club for drinks and conversation. He is, in effect, an ordinary guy and it's a role that – perhaps unexpectedly – fits the ever-able Robinson like a glove. He's not alone here. One of his friends, district attorney Frank Lalor, is played by Raymond Massey, an actor adept at playing imposing and even sinister figures and who also completely convinces in this more relaxed role. There's almost a sense here that when the two hang out together with the third member of their friendship trio, Dr. Michael Barkstane (Edmund Breon), that their characters are closer to the actors' true-life personalities than the roles in which they are more commonly cast. This, I would argue, is this film's first real hook – when these guys sit around and chat over a drink, I quickly bought into them as real people. Even before the main story gets under way, the film had my full attention.

That Wanley is able to chill out so completely with his friends is partly down to the fact that he had packed his wife and children off for a summer vacation that his current workload prevents him from joining them on. When, during the course of their conversation, he complains that that his life has become one of routine and convention and devoid of adventure, Lalor firmly suggests that's a good thing for men of their age, one of several small pointers here to where the plot will soon head. As his companions get ready to depart, Wanley admits that his desire for adventure is purely theoretical and that if, for instance, he were to meet the subject of the alluring painting in the store window next door, he would probably mutter something idiotic and run like the Devil. Care to guess what happens next?

It's when Wanley leaves the club later that evening and stops to take another look at the portrait that the woman who posed for it, Alice Reed (an impressive Joan Bennett), makes her aforementioned appearance. Instead of fleeing as predicted, Lanley instead converses politely with her and even accepts her invitation to join her for a drink, after which he accompanies her back to her apartment to see some further sketches of her done by the portrait's artist, a rather nice reversal of the male pickup cliché of inviting a woman back to his place to look at his etchings. Jeez, does anyone else remember that crap now? The two continue drinking, and although Alice has an inescapably seductive air about her – she dresses alluringly in black and her body language and the manner in which she addresses Wanley suggests she's giving serious thought to ripping his clothes off – Wanley behaves like a gentleman, albeit one who is likely mulling the pros and cons of what could unfold later. As they struggle to open a second bottle of champagne, however, a man (Arthur Loft) unexpectedly enters the apartment, angrily accuses Alice of playing around and hits her. When Wanley attempts to intervene the man socks him in the jaw and attempts to strangle him. The diminutive Wanley is no match for this burly brute, and as he desperately reaches for something to fight him off with, Alice places the scissors they were using to prise open the champagne bottle in his hand, with which he repeatedly stabs his attacker. The man is killed, but just as the badly shaken Wanley is about to call the police the thought of what this will do to him and his family gives him second thoughts (this is not spelt out , but speculation is easy here). The equally rattled Alice reveals that as far as she's aware nobody knew that she was seeing the man and that he was so secretive about their affair that he never even told her his real name. Wanley thus suggests that he disposes of the body at some far away location where its discovery could not possibly point even the smallest finger of suspicion at them.

And it all goes smoothly and no-one ever suspects them of the crime and they go on to live happy and untroubled lives. Yeah, right. This is 1940s American cinema, this is film noir, and this is director Fritz Lang on ferocious form. And Wanley is an ordinary guy with no practical experience of criminal activity who has to dispose of a body without leaving a single piece of evidence anywhere. What could go wrong? Oh boy, you name it. What follows is a lengthy but nail-chewingly brilliant sequence in which Wanley has to smuggle the dead man out of the apartment and into his car and drive it to a distant location for disposal, and rather than try and fool us into thinking he'll pull this off without a hitch, Lang and producer-screenwriter Nunnally Johnson (whose script was based on the novel Once Off Guard by J.H. Wallis) instead elect to highlight all of the things that could help identify him as the killer. If that wasn't enough, when the body is discovered the victim is identified as wealthy business promoter Claude Mazard, and his murder thus makes the national news and becomes the subject of a major police investigation.

The Woman in the Window is one seriously tense film, with the wind-up delivered by the above detailed sequence sustained once the police investigation gets under way, the details of which Lalor – who as district attorney is effectively in charge of the case – just can't resist sharing with his closest friends, unaware that one of them is the man his team are looking for. Indeed, so close and long-standing is their friendship that every time a clue crops up that should theoretically make Wanley a suspect, Lalor and Barkstane laugh it off as unfortunate coincidence, a state of affairs you just know can't last. Then if things weren't already complicated enough, up pops Heidt (Dan Duryea, here laying a template for a range of sleazy characters he would play in the years to come), a crooked ex-cop who was working as Mazard's bodyguard and is now looking to blackmail Alice with what he knows and has (correctly) surmised about her and Wanley.

Structurally, The Woman in the Window really knocks it out of the park, repeatedly winding us up to the point where Wanley or Alice seem doomed, then offering a small glimpse of hope that it resoundingly dashes, sometimes by playing with our expectations and by fooling us into believing that a scene is going one way before pulling the rug from under our overconfident feet. Lang's direction is precise and bristling with purposeful camera angles and movements that drive the narrative forward but rarely draw attention themselves (a shot of Alice and Heidt that you expect it to cut to mid-shot but stays wide in order to catch Heidt's reflection in a mirror when he stands up is a rare example). He's ably aided by cinematographer Milton Krasner (who later worked on Lang's Scarlett Street and Robert Siodmak's The Dark Mirror, two other 40s noirs of serious note) and first-time editor (and producer-screenwriter Nunnally Johnson's daughter) Marjorie Fowler, who does a fine job of building pace and tension but also has the unenviable task of trying to disguise a handful of (still visible) continuity errors, plus a frankly outrageous jump-cut when Wanley and Alice are discussing the blackmail problem whilst being symbolically photographed through fence railings that look portentously like the bars of a jail cell. We can only presume that Lang didn't get the coverage he needed to cover the join, but the continuity of sound and camera movement just about carry it anyway. This is why editors are even a great director's best friend.

It all builds compellingly to a point where you genuinely can't imagine how Wanley and Alice will be able to escape their looming fate, and then…

And then…

OK, major spoiler warning here. I just can't sign off on this review without discussing the film's final twist, and that means giving away the ending. If you've never seen the film then I'd skip to the technical specs, which you can do by clicking here. If you have seen it then you'll know full well what I'm about to cover and probably already have views of your own on Lang's decision-making here. It's also a twist that I find myself responding to differently now to how I did when I first saw the film many years ago, and it's worth outlining why. So, warning delivered, here comes the spoiler.

When I first saw The Woman in the Window back in my late teens, I still clearly remember my reaction to the film's final twist. I was seriously pissed off. Let me be clear, I loved the film and was utterly gripped by its story and characters, but just when everything seemed hopeless and the film had delivered the darkest of noir endings, Wanley wakes up and it was all a dream. What? A dream? You have to be kidding me! I would imagine that this will be the reaction of a fair few who come to the film for the first time from a modern perspective, when "it was all a dream" has become one of the lamest of all lame cop-out twists, one that hit its nadir in the first episode of season 10 of Dallas when it was revealed that the whole of the previous season was a dream, something that outraged the fans and gave haters a very big stick with which to mockingly beat the series.

Coming back to The Woman in the Window, this time aware that this final twist awaited me, was still a hugely enjoyable experience, and watching it a third time after taking on board the comments made about the twist in the special features, I was able to view the film in a slightly different light. If you accept that the adventure that Wanley embarks on is a dream born of middle-aged male fantasy, then the film becomes an intriguing exploration of the very things outlined in Wanley's earlier conversation with Lalor and Barkstane, particularly about what men may desire but elect not to act on when they settle into a routine, as well as Lalor's warning about how a single moment of carelessness can lead to downfall. This also makes sense of the young and attractive Alice's instant fascination with this crumple-faced and far older man that she meets on the street and knows precious little about, as well as the seductive overtones of her behaviour when Wanley accompanies her back to her apartment, something he would probably never do in real life anyway. It also ties into Wanley's opening college lecture, titled "Some Psychological Aspects of Homicide," in which he makes a case for morally differentiating between premeditated murder and killing someone in self-defence, and does so in front of a blackboard peppered with key words from the psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud, whose name is writ large and one of whose most famous works was The Interpretation Of Dreams. And once Wanley wakes and is approached outside by a woman whose face is also reflected in the window containing the portrait, he does indeed mumble something and run away as he told his friends he would. In the film's defence, it's probably also worth noting that this may be the first time the "it was all a dream" twist was used in a major American motion picture (I'll bet money that I'm wrong there, but it's certainly an early adopter) and that it thus wouldn't have been the cliché on its initial release that it later became, although it apparently still got up the noses of a number of contemporary critics. It does, however, provide a useful get-out clause for a film whose ending would otherwise have fallen foul of the restrictive production code – no-one needs to be punished for a crime if the crime in question never really took place.

Where the above interpretation does have a potentially negative impact on the film is that it robs the unfolding drama of its sense of danger because no matter how invested you are in Wanley as a character, if you know that that the threat is just a product of his imagination, it's hard to get as wound up by the story a second time around. At least that's the theory. What really struck me about my first viewing of the film in some while was that even knowing that this was later to be revealed as a dream and that Wanley is never really in danger, it's so convincingly performed and so beautifully plotted and directed that I still found myself getting wound up by every unfortunate turn of events. Just the concept of placing the hapless Wanley close to the centre of an investigation into his own wrongdoing provides its share of tense moments, as he is drip-fed confidential information on a case whose every breakthrough seems to implicate him, evidence Lalor is effectively blind to because the two are such close friends and the very idea that Wanley could commit such a crime is just not on his radar.

Whether this ending does serious harm to an otherwise great film or is a daffy final twist to a tale that bristles with surprisingly and nerve-shredding turns of fate will be very much down to the taste of the individual viewer. For myself, I've learned to live with and see fascinating things in a plot twist that the first time around had me screaming in disbelief. And I'm sorry, but the rest of this remarkable film is just too damned good to let a single narrative decision – even one on this scale – detract from what Lang and his collaborators otherwise achieved. My advice is to live with it, learn to embrace it, and enjoy what remains one of the finest and most compelling of Lang's American movies, and a masterful early example of a now-beloved subgenre of the crime movie that had at this point yet to be given a name.

An excellent 1.37:1 1080p transfer with a few imperfections, all of which are clearly down to the variable condition of the source material. For the most part, the contrast is very nicely balanced, the detail is crisp and a fine film grain visible throughout. It's clear that more than one source was used for the restoration, however, which results in a few noticeable shifts in quality, sometimes midway through a shot – in one, the fine detail on the fittings in a room all but vanishes as the quality drops suddenly, only to return to form a few seconds later. There is also some occasional minor picture jitter, and a more spectacular jump towards the end of the film, plus a single instance of brief but spectacular damage when Wanley is thinking twice about calling the cops after killing Mazard. But these are small distractions in an otherwise strong transfer.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack also has a couple of small pops in line with the above-noted damage, but is otherwise in good shape, with clearly rendered dialogue, music and effects within the expected age restrictions in the dynamic range, and very little trace of background hiss or fluff.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary by Imogen Sara Smith

Wow. No matter how much you may have read into every aspect of The Woman in the Window, I have a feeling that film critic and historian and author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City Imogen Sara Smith is going to open your eyes to a hell of a lot more. This is a fascinating commentary in which Smith provides a shedload of information on the film, the director, the screenwriter/producer, the cinematographer and the lead actors, but also peppers this with interesting trivia – I was unaware, for instance, that one of Wanley's only briefly seen kids is played by a young Robert Blake – and observations that could easily be dismissed as over-analysing, but which are all persuasively argued and make perfect sense given Lang's obsession with detail. Smith picks up on some casual sexism in the script, makes an interesting case for the sub-subgenre of 'Portrait Noir' and inevitably has her own opinions on the final twist. There's tons more, all good. An excellent extra.

Framed: A Video Essay by David Cairns (22:25)

A typically thoughtful video essay by the soft-spoken Cairns, who verbally lays out his case under extracts from the film, some of which are more relevant than others to the points he is making. He discusses the theme of destiny in Lang's cinema and life, producer-screenwriter Nunnally Johnson, actors Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea, Hollywood Freudianism, the problematic shoot, and more. Like Smith, he picks up on how the straw boater hat worn by Mazard becomes a key motif in the film (this may sound fanciful, but it really makes sense), and makes a pertinent point about how the final twist was the only solution to an impossible problem in a Hollywood film of its day.

Original Theatrical Trailer (1:43)

A briskly paced trailer that darts all over the film's timeline with its chosen extracts.

Booklet

As soon as I saw that the lead essay in the booklet that accompanies the film was by Eureka and Indicator regular Samm Deighan, I knew I was in for a damned fine read and it didn't disappoint, though it's worth knowing that Deighan reveals the film's final twist up front and proceeds to discuss the film from the viewpoint of how this affects the action that precedes it. Short version – don't even glance through this before your first viewing of the film. Once you have seen it, however, I can almost guarantee that this essay, in common with Imogen Sara Smith's detailed commentary, will enhance your appreciation of the film and prompt you to view elements of it in a new light. This is followed by another fine essay on Lang and The Woman in the Window by freelance film journalist and writer Amy Simmons, with particular focus on the character of Alice. Also included is a sizeable collection of poster reproductions and – a valuable grab this – three pencil drawings of early concept art.

Although one of the earliest examples of a subgenre that had yet to be recognised as such, The Woman in the Window is widely acknowledged now as classic of film noir, and any issues anyone might have with the final twist should not take away from the brilliance of what precedes it, in whichever light you choose to view the film. Despite some small imperfections in the material used for the restoration, the transfer is otherwise impressive and the special features, though limited in number, all contributed greatly to my appreciation of the film. Highly recommended.

|