|

The

term 'postmodernist' is thrown about quite a bit these days.

It's hardly surprising – the sometimes tiresomely self-aware

nature of so much recent western TV and film material seems

to be deliberately targeted at an audience who communicate in

part by referencing popular culture, some of which – Buffy,

The Simpsons, Spaced,

etc. – is already steeped in pop cultural quotation. The

self-referential nature of postmodernist cinema can extend

to the very structure of the film itself, from a seeming

awareness of the characters that they are in a film – as

in Wes Craven's Scream series – to a complete

disregard for the idea of keeping the filmmaking process

hidden. At its most drastic, that substructure will

intrude into the narrative, most recently exemplified

by Michael Winterbottom's A Cock and Bull Story (in which the original novel is amusingly described as "Postmodernist

before there was any modernism to be post about"),

where the historical drama eventually gives way to the background

story of its production, which itself includes an interview

being conducted for inclusion as a special feature on the eventual DVD release

(it was, too).

Although

generally regarded as a relatively recent phenomenon, this

practice of cinematic self-deconstruction was small-scale

popular back in the 1960s, where it had less to do with

targeting the short attention span audience, being more an

expression of the influence of the avant garde and hallucinogenic

drugs on a new breed of young filmmakers looking to shake off the traditionalist

styles of their industry predecessors and break new artistic

ground within the feature format. This was a time of radical

change, of protest and experimentation in all walks of life

and art, so why not cinema or even television? Often regarded

as just a fun TV show built around a manufactured pop group,

the cheerfully freewheeling and mildly anarchic style of

The Monkees, for example, regularly included

elements that would today be instantly identified as postmodernist.

The concept was taken a few leaps further with its

1968 big screen incarnation, Head, when writer

Jack Nicholson (yes, that one) and director Bob Rafelson

threw artistic caution to the wind by fragmenting the narrative,

employing graphics and editing techniques that drew attention

to the filmmaking process, visually and aurally referencing

a number of external media sources, and working in a critique

of the very show and characters that they were presumably

employed to celebrate. At one point, the film even stops

when one of the cast is unhappy with his dialogue and the

entire crew enters the shot to reset the scene and discuss

how to proceed.

This

sort of experimentation was by no means confined to western

cinema. The very nature of experimental film as an outsider

art form created a bond between its practitioners of all

nations, each aware of the work of the other and inevitably

influenced by them, and in the late 1960s the influence

of the avant garde was starting to spill over into independent

feature production. In Japan in 1969, you'll find no more

striking example of this than Matsumoto Toshio's Bara

no sōrestsu, or Funeral Parade of

Roses.

Everything

about the film seems to kick against established values,

whether they be those of mainstream cinema or society at large,

and to a degree that a staunchly traditionalist audience

would still be outraged by even today. For a start, most of the

lead characters are gay, and not quietly in-the-closet gay

but flamboyantly and cheerfully so, and transvestites to boot.

Most are played by gay men rather than trained actors (hooray!)

and are portrayed as feminine rather than effeminate. The

central character of Eddie, as played by the enigmatically

named Peter (no surname), is so strikingly convincing that

there are times when she – I use the feminine here deliberately

and respectfully – really does look beautiful, and I'm talking

from a (hopefully progressive) heterosexual male viewpoint. By this point, we should already have lost the self-proclaimed

moral majority, but it doesn't end here. The story at the

film's heart is a take on Oedipus Rex, Sophocles'

everyday tale of patricide and incest, but with a twist

here that is just guaranteed to offend the prudish. Oh yes,

there are also some erotically charged gay sex scenes, a

rejection of the traditional values of society, and an ending

whose violence is so shocking I actually yelped out loud.

Oh, it's great stuff.

On

the surface, this is a tale of personal rivalry between Leda,

the mama-san (the madam, if you will) of a Shinjuku gay

bar, and Eddie, the most attractive of the bar's hostesses,

both of whom are doting on drug dealer and bar regular Gonda.

Their rivalry (and the film's break with cinematic traditions)

is signaled early on as Leda looks in a mirror and the phrase

"Mirror, mirror on wall, who is the fairest of them

all?" pops up as a non-diegetic graphic, only to have

Eddie appear behind her at that very moment. This love triangle

plays almost as background detail to the everyday

lives of Eddie and his friends, as they party, take drugs,

make out, go shopping and work the customers in the Bar

Genet. In another pleasing kick against expectations, the

bar's patrons are a thoroughly manly bunch and not remotely

effeminate, none more so than Gonda (emphasised perhaps

by the casting of Yoshio Tsuchiya, most famous in the west

for his role as the young Rikichi in Kurosawa's Seven

Samurai). They also include a black US Vietnam

war veteran, itself is unusual in a Japanese film of the

period, but accurately reflective of the more international

nature of Tokyo's Shinjuku district – renowned as the city's

liveliest quarter – in which the bar is located.

Structurally, the film consistently plays games with film

technique, fracturing the narrative in a way that invites

a variety of possible readings. One sequence, for example,

is repeated shot for shot later in the film, while another

is interrupted mid-way by seemingly unconnected scenes,

only to return later to the exact moment we left it. Are

these memories, flashbacks, premonitions, or drug trips?

Perhaps they're none of these – according to director Matsumoto, this approach

was intended primarily to provide a Cubist view of the lives

of its main protagonists.

Elsewhere,

the experimentation is deliberately playful, with a wildly

distorted video image of the quelling of student anti-war

protests eventually revealed to be the result of a dodgy

indoor aerial being deliberately manipulated for Guevara,

the film's in-story filmmaker. A similar and equally successful

trick is played later on, when naturalism jarringly shifts

to a William Burroughs / Anthony Balch style cut-up sequence,

an extract from one of Matsumoto's own experimental shorts

that Guevara is playing for the gang. Brief, almost flash-frame

shots can crop up anywhere, some seemingly abstract, some

symbolic, some of them memories. Probably the most initially

disorientating style shift occurs when the narrative is put

intermittently on pause in order to interview the actors

about their roles and their lifestyle, or to show the crew

shooting the scene you have just been watching. In one respect,

it's like having a DVD of a film, complete with the standard

extras of cast interviews, behind-the-scenes footage and

earlier short films by the same director, and seeing them

blended into a single production.

But

it works. And then some. Initially, the sudden shifts in

style and tone can seem confusing and directionless, but

as the narrative unfolds and a level of consistency is maintained,

many of the seemingly abstract pieces fall into place.

Certainly a second viewing clarifies a lot, and a few of

the remaining gaps caused by temporal and cultural differences

(a 2006 UK audience cannot really be expected to recognise

a parody of a 1968 Japanese TV commercial after all) are

usefully filled in by the detailed commentary track (more

on that below). A variety of media is incorporated, including

still photographs, performance art, quotation captions,

a brief fake film trailer, and direct-to-camera critical

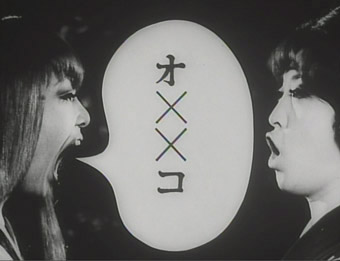

comment. At one point, Leda and Eddie stand off in mock western

gunfight mode armed with toy guns, and the ensuing trading of

insults is displayed as manga-style speech bubbles, including

a half censored word (subtitled appropriately as "c**t").

The look of the film is equally adventurous, with overexposure,

strobe lighting, solarisation and a fair few other tricks used

to sometimes deliberate and emotive effect.

It's

rumoured that the film was a favourite of Stanley Kubrick's

and that it had an influence on the look of A Clockwork

Orange, which was released just two years later. Though this

may be a stretch for the most part, there are certainly

a few small but significant similarities, not

least the speeded-up long shot of two drug dealers hiding

their wares to the accompaniment of an accelerated version of The

Can Can (reworked by Kubrick with the William Tell

Overture for Alex's two-girl sex scene). It also shares

with Kubrick's film a consistently offbeat use of source

music, with a number of scenes engagingly mismatched with

a fairground version of Ach Du Leiber Augustine,

better known to American schoolchildren and Simpsons

fans everywhere as the Hail to the Bus Driver song.

In

the end, it's easy to see what would excite someone like

Kubrick – a resolute outsider and a true visionary, working

in an system that he somehow managed to force to dance to

his tune – about a film that ticks almost every box of the

Outsider Cinema check sheet. It's daring, exciting, innovative,

shocking, funny, occasionally a little frustrating, but

an absolute must-see for anyone who believes that true cinema

should challenge and confront rather than simply placate.

This

appears to be another of Masters of Cinema's licenses from

Toho in Japan, adapted for the UK market with English subtitles

on the film and extra features. As with some other Toho

licences (The Naked Island, Humanity and Paper Balloons),

the transfer is strong in some areas, but weaker in others.

The strengths include the clarity of image and the clean print, which is excellent, but the trade-off is a

sometimes narrow contrast range and black levels that fall

more into the realm of dark grey. Once again, the intention

appears to have been to preserve shadow detail – crank the

brightness down on your TV and you'll get better blacks,

but lose all detail in darker areas and scenes. Occasionally,

the image has an overexposed look, but this is clearly a

deliberate artistic decision by the director and his DoP

– the suggested innocence of the dominant whites in the

opening sequence, for instance, works particularly well,

and looks great here. The picture is famed in its original

4:3 ratio. As with the simultaneously released Fantastic

Planet, this is an NTSC disc, avoiding any conversion

issues.

The

original mono soundtrack betrays the age and low budget

a little, with a very slight background hum and some clipped

trebles, but is otherwise more than serviceable.

The

subtitles are clear and largely well translated, though

do sit a little high in the frame. Interestingly the borrowed-from-English

Japanese phrase "gay boy" is translated on the

extras as "gay man" but on the film as "queen."

The

absolute prize here has to be the Commentary

by director Matsumoto Toshio, which is conducted in Japanese

but very well subtitled in English. Matsumoto is a busy

talker and proves a wealth of detail on just about every

scene, including the origin of all quotes, details on every

guest appearance (and there are many), the specifics of

how scenes were devised and shot, how individual people

were cast, and the various cultural and media references,

which frankly few if any would pick up on today without

these pointers. He also explains some plot points that I

completely failed to register even two viewings in, and

the sheer volume of information provided here added greatly

to my appreciation of the reasoning behind the film and

its structure.

There's a Director Interview

(22:54), also in Japanese with English subtitles, which

although inevitably has some crossover with the commentary,

does expand usefully on the information provided there,

especially when talking about the casting process or his

own influences and graduation to feature film production

(this was Matsumoto's debut feature).

The

Original Japanese Trailer (3:27)

is an eye-opener in itself, from its opening 25 second silent,

static close-up of Eddie, to the nudity and sensationalist

sales pitch, promising that you will see "actual sexual

perversion exposed!" Despite its age, I'd be surprised

if even Queer as Folk would feature a trailer

as erotically suggestive as this. One warning – it does

include footage from the final sequence, which you should

definitely not see in advance of the film proper.

The

Poster Gallery contains reproductions

of 10 of the original posters.

And

finally we have the expected, typically well produced Masters

of Cinema Booklet, which contains

two detailed and interesting essays – in Timeline for

a Timeless Story, filmmaker Jim O'Rourke examines the

cultural lineage that led to the film, while Roland Domenig

places it in the context of the Art Theatre Guild. These

essays are particularly well selected as they build on rather

than reproduce information found on the disc itself.

Funeral Parade of Roses is a splendid

choice for the Masters of Cinema label, a film whose appeal

is completely outside of the mainstream but which deserves

a place in cinema history for its boldness of technique,

plus its unashamed and warmly sympathetic approach to characters

and situations that are too often the victim of idiotic

caricature. Issues with contrast and black levels aside,

this is another fine release for MoC, for the film itself

and a richly informative commentary track. Recommended.

|