| |

Q: How, in your opinion, are the influences of the United

States manifesting themselves upon Europe and in Europe? |

| |

A: Through the most emphatic garbage, an ignoble sense of money,

indigence of ideas, savage hypocrisy in morals, and, altogether,

through a loathsome swinishness pushed to the point of paroxysm. |

| |

Benjamin Péret, transition no. 13, 1928 |

The above exchange is culled from Bill Grantham's book Some Big Bourgeois Brothel, which places Gallic resistance to Hollywood hegemony, particularly French quotas on US entertainment imports, at the apex of historic Franco-American animosity. Those fearing its presence announces an imminent attack on the United States in general, and Otto Preminger's The Man With the Golden Arm in particular, need fear not. Fulsome praise of that film follows and any comments detrimental to the standing of the US below are offered in the spirit of (wary) friendship and (qualified) respect. Péret's forthright comment is prominently placed simply to ground a cursory consideration of Preminger's work in the context of views that deserve close scrutiny, but are all too often excised from public conversation by the manufacturers of consent or howled down by shrill cheerleaders of the American way of life. The US should be big enough to stand a little constructive (film) criticism.

Grantham points out that European hostility to Americanization began in the early nineteenth century, with Baudelaire, but was particularly pronounced in the interwar years. Péret's reply to Eugène Jolas's question captures the truculent tone that pervades transition's 'Enquiry Among European Writers Into the Spirit of America'. We might expect as much from a survey published during an era of angry manifestos, at the high tide of modernism, in an avant-garde journal distributed from the Parisian redoubt of Sylvia Beach's Shakespeare and Company. Deep-seated disapproval of the US, though, spread far beyond rive gauche surrealist circles and long outlived Péret. European projections of the US as a rapacious, rotten continent riddled with guns and riven with racism may smack of the pot calling the kettle black arse, but they contain a grain of truth. There is sufficient force to the picture of America as a land of surging inequality and home of crass commercial culture to make many baulk at triumphalist talk of 'the land of the free and the home of the brave'.

Novelist Paul Bourget spoke for many when, shortly before his death in 1935, he optimistically defined the difference between the two very different continents: "Equal social possibility – such is the democratic formula in America. Equal social reality – such is the formula in Europe." There was a widespread perception, back then, that the US had machines and money but no culture while Europe had culture aplenty but few machines and little money. The idea that the US lacked and lacks culture is as ludicrous as it is offensive. That mighty continent is, after all, the world in one country – as American as apple pie and french fries, one might say. It is the heartland of capitalism; the land of a thousand dances and a million songs, of the Charlston and Chattanooga Choo Choo, button-downs and bourbon, Cadillacs and Pontiacs, baseball and basketball, the blues and jazz, saxophones and vibraphones, soul and rock 'n' roll, levis and loafers, the Lindy Hop and hip-hop, Motown and hoedowns; the cradle of Albee, Algren, Dos Passos, Drieser, Lowell, Melville, Sandburg, Steinbeck, Whitman, Wharton, and a thousand others who graced the republic of letters; and, ultimately, it is the home of Hollywood, 'the dream factory'.

Similarly spurious and hostile attitudes were equally commonplace across the Atlantic. Not even gratitude for the gift of the statue of liberty long assuaged American animosity toward France. Grantham juxtaposes Péret's comment with one from F. Scott Fitzgerald: in a letter to Edmund Wilson, dated May 1921, he says, "God damn the continent of Europe. It is of merely antiquarian interest . . . France makes me sick . . . culture follows money, and all the refinements of aestheticism can't stave off its change of seat." Fitzgerald goes to the heart of the matter: Europe represented the past, the US the future, a new imperial project was usurping the old.

In a Partisan Review interview of 1947, Simone de Beauvoir said: "The idea that the choice between art and money was imposed by American society was an early and potent one for the French imagination . . . the newness of America signified a lack of tradition and roots, a source of horror to many; although, for others, precisely this characteristic contained America's mythic appeal." George Orwell located that mythic appeal in an admirable rootlessness. In a Tribune essay on Mark Twain, he mourned a lost tradition of dog-eat-dog meritocracy he found in Twain's core theme, "This is how human beings behave when they are not frightened of the sack."

For Orwell, the golden age of the American pioneers may have been wild and violent but, "at least it was not the case that man's destiny was settled from his birth, as it was in class-bound Europe of the ancient régime. He says: "the 'log cabin to White House' myth was true while the free land lasted. In a way, it was for this that the Paris mob had stormed the Bastille, and when one reads Mark Twain, Bret Harte and Whitman it is hard to feel that their effort was wasted." It is hard to feel it was wasted when watching the films of Otto Preminger. It is impossible to feel so when watching The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), his groundbreaking film set in North Side Chicago and the dog-eat-dog demi-monde of those unafraid of the sack.

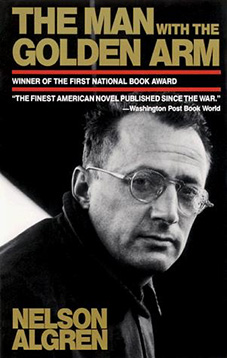

For many Europeans, the perceived threat to the old world from the new arrived in the guise of a destructive, dynamic force moulding the universe in its own image: the America of mass production, Moloch, and the machine age. Frankie Machine, the forlorn junkie hero of The Man With the Golden Arm symbolizes both the America dream and the failure of the idea that 'all men are created idea'. Preminger's film, adapted from a novel by Nelson Algren, a European manqué and great American outsider, is of special interest in that it represents both classical Hollywood and an essential corrective to its lacunae. It has much to say within the interrelated debates surrounding Franco-American relations, the relationship between the auteur and industrial film production so essential to the development of modern film criticism, and the relationship between machines, money and images so central to cinema.

| Godard & Co and Preminger |

|

While eruptions of antagonism between totemically European France and the US predate the birth of cinema, it is in cinema that transatlantic mutual suspicion have been most prominently and symbolically expressed. Expressions of love for American culture were, naturally, manifest in cinema too. Everyone who loves cinema must be grateful for America's contribution to the seventh art but none have been as grateful as the cinephiles of post-war Paris, who divided up the city's ciné-clubs and cinemas, along aesthetic or ideological lines, like Chicago gangs staking out territory during prohibition. Equally grateful to the Americans for liberating their city, conscious of the deep debt liberty owed the US for its contribution in two world wars, and racked with guilt about collaboration, they embraced all things American with passion. Few went as far as Jean-Pierre Melville (who drove a Cadillac, wore a Stetson, and named himself after the author of Moby Dick), but the critics of Cahiers du cinéma who rose from those cinephile ranks, and who'd been starved of American films during the war, worshipped at the altar of Hollywood.

The iconoclastic set of ideas grouped under the rubric la politique des auteurs initially arose from the Cahiers critics' attacks on mainstream French cinema (le cinéma de papa) and then broadened out to encompass a concomitant defence both of Hollywood and the cultural legitimacy or specificity of cinema. Hollywood, a mass production system for mass consumption, caused various theoretical problems for the young Cahiers critics, clashing as it did with the traditions of literary criticism and assumptions about art from which they began. Their ineffective solution was to foreground those directorswho, like Preminger, carved out freedom from within the confines of the studio system, demonstrated thematic consistency, and expressed themselves in mise-en-scène choices such as long takes and deep focus. As Andrew Sarris noted, auteur theory was also an exercise in exploration and discovery, in finding auteurs within the studio system. It is partly because he was the archetypal insider-outsider that Preminger became such a significant, even mythic figure for the critics of Cahiérs du cinema - every bit as important for the 'Hitchcocko-Hawsians' of the French New Wave as Samuel Fuller, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, Frank Tashlin, et. al, but, perhaps, for more complicated reasons.

Preminger sits on the fault line between mainstream, classical Hollywood and anti-hegemonic independent cinema. Even while working as a contract director at Twentieth Century Fox he had fought for his independence. After his fourth Hollywood film, In the Meantime, Darling (1944), he had begun producing his own films and by the time he came to make The Man With the Golden Arm he was already firmly established as an independent director-producer. Andrew Sarris called him a "director with the personality of a producer."

By the 1950's the decline of the studio system and legal challenges to the monopoly of the major studios had levelled the playing field and encouraged a trend towards independent production. This was the salvation of Preminger's anchor company, United Artists. Founded in 1919 by Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffiths, UA was a not-for-profit distribution company that refused to consolidate to survive and doggedly faced down the rigged racket of vertigal integration through a series of crises. It was seldom plain sailing.

With the company close to bankruptcy, its surviving founders Chaplin and Pickford relinquished control in 1951 and UA began financing as well as distributing and promoting films, and became the first studio without a bricks and mortar 'studio'. At its best, the company was exemplary of an independent ethos. As Preminger said: "Only United Artists has a system of true independent production . . . After they agree on the basic property, i.e. the projected film, and are consulted on the cast, they leave everything to the producer's discrimination."

Preminger took full advantage the freedom United Artists afforded him. Like independent producer Sam Spiegel – another Austrian émigré, fellow graduate of the University of Vienna, and stablemate at UA - Preminger was a tough Jewish non-conformist who despised small-minded bigots. He gained the nickname 'Otto the Terrible' for his fiery temper and combative disposition, both of which he exercised liberally in his confrontations with the National League of Decency. Founded in 1933 by Catholic Archbishop John McNicholas, the League aimed to 'purify' cinema, protest against films deemed to constitute "a grave menace to youth, to home life, to country and to religion," and enforce the antediluvian Motion Picture Production Code, the infamous 'Hays Code'. Preminger was having none of it.

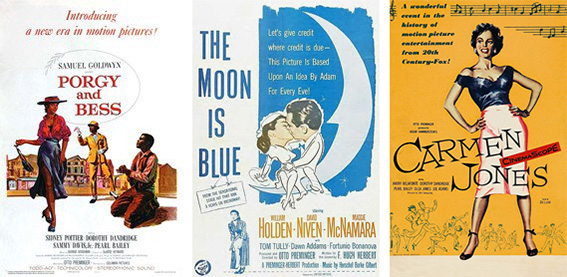

It is hard to underestimate the important of Preminger's single-minded refusal of constraints. Put bluntly, he advanced the cause of freedom of speech and changed film history. From his first film as an independent director-producer, The Moon Is Blue (1953), onwards he courageously swam against the tide of Hollywood censorship. That film was banned in several states, shown only to adults in Chicago, and released without the Hays Code's Seal of Approval because, look away now children, Preminger refused to remove the purportedly risqué words 'virgin', 'pregnant', 'seduce', and 'mistress' from the script. He again refused to capitulate to censorship by using the taboo words 'rape', 'sperm' and 'sexual climax' in Anatomy of a Murder (1959). The film was eventually released with the seal and the Hays Code was dead in the water. Preminger opposed institutional racism with equally efficient definance in Carmen Jones (1953) and Porgy and Bess (1959) – the first Hollywood films with all black casts. He also challenged homophobia and McCarthyism in Advise and Consent (1960), which contains the first Hollywood scene set in a gay bar and stars blacklisted left-wing actors Will Geer and Burgess Meredith. And, as if that were not enough, Preminger dealt McCarthyism a further, fatal blow by hiring and openly crediting screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, most prominent of the Hollywood Ten, for his work on Exodus (1960).

| The Man With the Golden Arm |

|

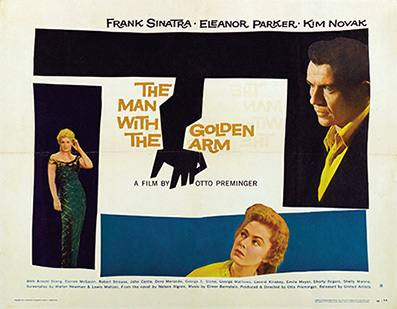

In The Man With the Golden Arm, Preminger contemptuously tears up the Hays Code's widely derided inventory of verboten subjects and lenthy list of 'Don'ts and Be Carefuls', systematically defying the Code's prohibition on representations of drug use and sympathetic treatment of criminals and women 'selling their virtue'. It is to United Artists credit that they backed him all the way. Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (1945) had broken fresh ground in its treatment of alcoholism but never before had heroine addiction been treated by Hollywood and seldom again would it be handled with such craft and compassion, insight and intelligence.

Junkie card sharp Frankie 'The Dealer' Machine returns from prison to his North Side Chicago haunts, his cold-water flat, and his neurotic, wheel-chair-bound wife 'Zosh' (Eleanor Parker). Although he's kicked his habit inside and is determined to set his life in order, his attempts to secure steady work as a jazz drummer are threatened at every turn. Frankie's skint, the local cops harass him at every turn, his old boss Schwiefka (Robert Strauss) wants him back at work in his gambling dens, pusher Louie (Darren McGiven) wants him hooked again, and Zosh, who trades on his guilt over the car crash that incapacitated her but is secretly able to walk, wants him back in her pocket. Sympathetic ex-squeeze Molly (Kim Novak), adoring punk mate Sparrow (Arnold Stang), and friendly neighbour Vi (Doro Merande) all root for Frankie, but the odds are stacked against him. Before long he's on the gear again, implicated in a murder, and forced to fight for his life by going 'cold turkey'.

The film steps straight into immortality with one of the most scintillating, high-octane title sequences in the history of cinema.* Fusing the jaggedly abstract, neo-cubist work of graphic designer Saul Bass and a rasping jazz-blues score from composer Elmer Bernstein, it immediately announces the film's debt to Film Noir and replicates the disorientated fragmentation of the addict's disordered psychology. The film never skips a beat from then on. As the narrative gathers pace, each scene heightens the tension we feel as Frankie struggles with his addiction and is knocked off kilter by the successive events that floor him. The film has the epic grandeur of greek tragedy and the intimate intensity of a haiku. Although it surrenders to a happy ending, of sorts, (in the novel Frankie hangs himself, in the film he survives) the darkness of damaged lives is there throughout. If Zosh is less sparky, more drippy than the shrewd woman Algren imagined, and if Vi is regrettably transformed from Algren's sassy, streetwise sister-in-arms into a pinched matron, each character, otherwise, rings with truth. The casting decisions Preminger made paid extraordinary dividends.

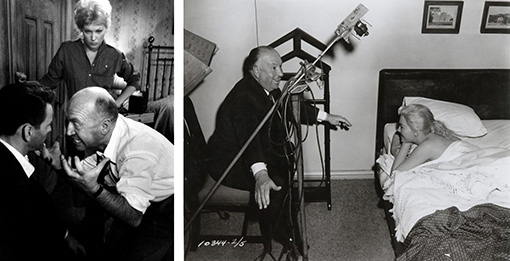

Frank Sinatra narrowly beat Marlon Brandon to the part of Frankie Machine, thereby securing revenge for having been pipped to the lead role in On the Waterfront a year earlier. The wounds were still raw on both sides when the two men were united in Guys and Dolls immediately after Sinatra's stint for Preminger. Two different styles of acting locked horns as well as two giant egos. Sinatra hated "all that method acting crap" almost as much as he hated Brandon and the two men only spoke to one another through intermediaries during a famously fractious shoot. Sinatra said: "I don't buy this take and retake jazz. The key to good acting on screen is spontaneity and there's something you lose with each take."

Fresh from having matched Montgomery Clift and Burt Lancaster stride for stride in Fred Zinneman's From Here to Eternity (1953), Sinatra's confidence in his own acting ability and approach was sky high. He makes the part of Frankie Machine his own by investing him with the same wounded, almost boyish vulnerability he'd brought to Angelo Maggio in Zinneman's film. It is a captivating performance that speaks volumes for his approach. Eleanor Parker and Doro Merande were, perhaps, sold short by Preminger's decisions to water their characters down, but Kim Novak's brittle, ice-maiden aloofness is as well suited to the role of Molly as it would later be to that of Madeline Elster in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958).

In a film of flawless performances and star turns, Arnold Stang's personification of Sparrow the likable, if oily grifter who dotes on Frankie bears special mention. There are clear echoes of Stang in Dustin Hoffman's portrayal of con artist 'Ratso' Ritzo in John Schlesinger's Midnight Cowboy (1969), a United Artists film that reworks the friendship of Frankie and Sparrow in that of Ratso and Joe Buck. Alexander 'Sandy' MacKendrick's Sweet Smell of Success (1957) is another United Artists film that was clearly influenced by The Man With the Golden Arm. The setting may have switched from Chicago's North Side to New York's Broadway but the same portrait of kicking-clawing-biting dog-eat-dog urban cynicism is present in both films. Emile Meyer plays a corrupt cop in both. Both are punctuated by Elmer Bernstein's thunderous jazz crescendos and enhanced by hip-speak that shows Nelson Algren and Clifford Odets at the height of their powers. There are even echoes in individual lines: for instance, Frankie says "I'm the kinda guy, boy, when I move, watch my smoke," Sydney Falco says "Watch me run a 50-yard dash with my legs cut off."

In his invaluable survey of Preminger's work, The World and It's Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber & Faber, 2008), critic Chris Fujiwara argues that the film tempers Algren's critique of American society. He says: "Preminger chooses to concentrate not on the "noir" motifs of doom and entrapment (elements which Algren's book emphasized), but on the hero's moral regeneration." Actually, Algren equally emphasized the socio-political forces bearing down on his characters and the damage they do to themselves. They share the "great, secret and special American guilt of owning nothing, nothing at all, in the one land where ownership and virtue are one," but they also "looked all day within upon some ceaseless horror there: the twisted ruins of their own tortured, useless, lightless and loveless lives." Preminger does copious justice to Algren's dazzling picture of the marginalized and maligned.

Nobody presented the case against the American way of life more courageously, consistently or precisely than Algren did in Nonconformity, his angry, articulate response to McCarthyism. Written in the early 1950s, as the raw wounds of his relationship with Simone De Beauvoir healed, it was prompted by the scaring experience of working with the tyrannical Preminger on The Man With the Golden Arm. Before we rush to congratulate the US on its capacity for self-criticism, it should be noted that Nonconformity was never published in Algren's lifetime. Of his brief time in Hollywood, he joked: "I went out there for a thousand a week. I worked Monday and got fired Wednesday.

The guy that hired me was out of town Tuesday." Billeted by Preminger in Sinatra's suite at the Chateau Marmont, Algren was almost immediately arrested with Hollywood grifters and, although Preminger bailed him out, he quickly withdrew from the film. So ended what Algren called, "my war with the United States as represented by Kim Novak."

Neither Algren and Preminger nor Algren and Hollywood were likely to form fast friendships. It surprised nobody when all parties went their separate ways after The Man With the Golden Arm, but it's a crying shame nonetheless. Algren regarded artistic endeavour as intrinsically rebellious and was contemptuous of those who played "the game of seeing who can serve the heaviest tip the fastest." He identified with the casualties of consumer capitalism, whom he regarded as his country's moral barometer and whose only crime, he felt, was to own nothing, in a land of milkshakes and money where ownership and virtue are one. It's easy to imagine Algren smiling, ruefully, at Mignon McLaughlin's aphorism: "Every society honours its live conformists and its dead troublemakers." Fortunately, we can look forward to two new documentaries on the great outsider, Algren and Nelson Algren: The Road is Nothing, the Road is All, both of which were completed last year. Kurt Vonnegut, another troublemaker, called Nonconformity, "A handbook for tough, truth-telling outsiders who are proud, as was Algren, to damn well stay that way." Few were tougher or more brave than Algren.

Otto Preminger was one of the great, undervalued directors of America cinema. Algren was one of the great, underrated American writers of the 20th Century. In honour of two supremely talented mavericks, I defy reviewers' convention and leave the final word to Algren. Here he is, at length, eloquent as ever, on his native land:

"We live today in a laboratory of human suffering as vast and terrible as that in which Dickens and Dostoevsky wrote. The only difference being that the England of Dickens and the Russia of Dostoevsky could not afford the soundscreens and the smokescreens with which we so ingeniously conceal our true condition from ourselves. So accustomed have we become to the testimony of the photo-weeklies, backed by witnesses from radio and TV, establishing us permanently as the happiest, healthiest, sanest, wealthiest, most inventive, tolerant and fun-loving folk yet to grace the earth, that we tend to forget that these are bought-and-paid-for witnesses and all their testimony perjured . . .

Do American faces so often look so lost because they are most tragically trapped between a very real dread of coming alive to something more than merely existing, and an equal dread of going down to the grave without having done more than merely be comfortable? If so, this is the truly American disease. And would account in part for the fact that we lead the world today in insanity, criminality, alcoholism, narcoticism, pyschoanalysm, cancer, homicide and perversion in sex as well as perversion for the pure hell of the thing. Never on the earth of man has he lived so tidily as here, amidst such psychological disorder. Never has a people lived so hygienically while daily dousing itself in the ritual slopes of guilt. Nowhere has any people set itself a moral code so rigid while applying it so flexibly. Never has any people possessed such a superfluity of physical luxuries companioned by such a dearth of emotional necessities. In no other country is such great wealth, acquired so purposefully, put to such small purpose. Never has any people driven itself so resolutely toward such diverse goals, to derive such little satisfaction from attainment of any. Never has any people been so outwardly confident that God is on its side while being so terrified lest he be not. Never has any people endured its own tragedy with so little sense of the tragic."

Network have released The Man With the Golden Arm on Blu-ray and DVD, making this the film's UK Blu-ray premiere. Naturally we were hoping to cover the Blu-ray release, but the DVD was sent out for review so we'll have to do with that for now. The image is certainly cleaner than I've seen it in the past on TV screenings, and the contrast is generally well balanced, with solid black levels and no burns-outs on the whites. The detail is pretty good (see the grabs below), but on a good sized TV the sharpness is a couple of notches shy of what DVD is capable of delivering on a well restored film of even this vintage and beyond. The picture is framed 1.66:1 and is anamorphically enhanced.

The Dolby 2.0 mono soundtrack has a slightly more restricted dynamic range than expected, resulting in voices that sound as if they're coming from a low-fi speaker rather than an HD surround system. There's no major damage to contend with. Optional English subtitles are available.

The only included extra feature is a rolling Image Gallery (2:28) consisting of posters, press stills and those garishly colourised front-of-house photos.

|