| |

"Not to have seen the cinema of Satyajit Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon." |

| |

Akira Kurosawa |

That's some accolade, the quote above, especially considering who it was delivered by. What true film enthusiast in their right mind would not immediately hunt out the work of a filmmaker who has been so championed? That sounds like the cue for a confession...

In retrospect I'm not sure how I managed to get through so many years of film viewing of material from every corner of the globe (can globes have corners?) without seeing a single work by a man widely regarded as one of the most important and talented filmmakers of the twentieth century. I certainly can't come up with an even remotely convincing excuse. After all, I spent almost every spare hour during the holidays in my college years at either the National Film Theatre or one of the many independent cinemas that London used to thrive on, and can't believe that at least a couple of Ray's films weren't showing during that time and know for a fact that a sprinkling of them have had TV screenings in the intervening years. And yet I've clearly blown every opportunity that presented itself. I'd love to lay out a kind of chaos theory-driven plot to explain how every single such chance has been missed by a unique combination of fate and circumstance, but I can't. That's not to say this isn't how it happened, of course, I just can't recall or remotely justify why I've arrived at this point with no Satyajit Ray films in my viewing experience.

This does, at least, offer me the chance to approach Artificial Eye's two three-film collections of Ray's work from the perspective of an eager newcomer rather than a learned cineaste (something I'd frankly never have the arrogance to claim myself to be), a position at least a portion of you will also find yourself in. Thus, while other reviewers will be able to tell you in some detail how these films fit into Ray's filmography and the development of his style, I'm looking at them as discovered cinema, films by a single director but independent of his other work, including the titles that have helped to define his career. For some this will leave my coverage wanting, for which I apologise, but you'll have no trouble finding the missing references elsewhere. I'm here to represent the first-timers, those who, like me, are on a path of discovery, and believe me this is cinema worth discovering. Knowing of Ray's films for so long and finally getting to see them is akin to having a box stored in the attic that everyone tells you that you should open but that you continually neglect to examine, and when you do so you find it crammed with fabulous treasure.

One aspect common to all three films that I was fascinated by and that I'm sure has been covered in a number of essays on linguistics, is the mix of Bengali and English in the dialogue, often in mid-sentence. Key points are often made in English following a Bengali build-up, while at other times the split seems almost poetically arbitrary, as in the proclamation by newspaper publisher Bhupati in Charulata: "My favourite smell," (in Begali) "the smell of printing ink" (in English). As someone who has become fascinated in recent years with the English language and the origins of specific words and phrases, this made me realise how little I know about this former colony and how the language of the occupier over time infected that of the native people.

And so to the films themselves.

| Mahanagar / The Big City (1963) |

|

If you're going to discover the work of a great director for the first time then this is the way to do it, with one of the fims that defines his talent and status. It's like coming the work of Ozu through Tokyo Story, a comparison I do not make lightly or randomly.

On the surface, Mahanagar is a tale of consequences of tradition-breaking in a society where tradition is valued and largely adhered to. But if you think that makes Mahanagar a specifically Indian story then you'd be wrong. The central characters, the Mazumdars, are in many ways a typical middle-class Indian family. The husband, Subrata (Anil Chatterjee), works in a bank while his wife Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee) tends to the house, looking after their young son Pintu, Subrata's ageing parents, and his unmarried sister Bani. Money is increasingly tight, however, and concerned that her husband is carrying the burden of being the sole wage earner, Arati decides that she will also look for paid employment, something that meets with the initial disapproval of the whole family.

Now if at this point you find yourself questioning my claims that this is not a specifically Indian story then I'd suggest a quick bit of social history revision. There are precious few cultures which have not been structurally patriarchal for much of their history, and the present equality of opportunity and status enjoyed by even the most progressive of societies is a relatively recent development, and one that many (men) still only begrudgingly accept and even vocally challenge. Back in 1963 when Mahanagar was made, the story could just has easily have been set in Japan, and could make for confrontational drama today if located in a devoutly Muslim society. And lest we get too smug in a country where women are now running companies every bit as calously as their male counterparts, a reminder of our not so distant past comes when Subrata tries to gently dissuade his wife's course of action by telling ther that "The English have a phrase – a woman's place is in the home." Crucially Arati's decision triggers no open arguments or heated exchanges, just hesitant uncertainty from Subrata and low-key disapproval from his parents. Only Pintu's refusal to communicate on the first day of work comes even close to melodrama, and that soon dissolves when he contemplates the toys the extra income might buy him.

The film is not specifically about Arati's decision to work but the ways in which it highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the family unit. Following his initial discouragement, the very next morning Subrata is scouring the newspaper in search of possible positions, a sign of his devotion to his wife that prefigures the uplifting determination and unity of the film's final scene. But Arati's position as a saleswoman for a company selling knitting machines, plus the money it makes her, awakens a sense of independence and control over her own destiny that challenges Subrata's traditional role as the family wage-earner. It also has a knock-on effect on Subrata's father Priyogopal (Haren Chatterjee), a retired teacher of some standing whose sense that his useful days have passed results in him touring the homes and workplaces of his ex-students in search of monetary hand-outs so that he may contribute to his own keep.

Key to why the film engages so effectively is that it never shouts at its audience or allows its characters to do likewise to each other. There are no kitchen sink explosions of anger, and characters and situations that time has made familiar rarely play out in the expected manner. Arati's job, for example, involves making door-to-door sales pitches, a favourite method in both film and theatre of humiliating a character through their profession, but not only is Arati welcomed into the homes that she visits, she quickly learns to enjoy the work. Likewise, there will be few who will react with surprise that her male boss Himangshu Mukherjee takes something of a shine to her, but it soon becomes clear that his interest is solely a professional one born of his admiration for her skills as a saleswoman. Later, a potential confrontation between Subrata and Mukherjee dissolves even before it has the chance to start when the two hit it off almost immediately and Mukherjee offers Subrata a job.

The drama is exquisitely developed and layered at every turn by the unfolding parallel stories. Arati's confidence appears to grow almost at the expense of both Subrata's and Priyogopal's self-esteem, which comes to a head with a family decision, one that fate then intervenes to reverse in a way that it would be unfair to reveal here. The character-centric handling of each of the three story strands, together with a string of beautifully nuanced and low key performances, invite full engagement with them all. Whatever your views on the family roles as defined here (and the ending should give you plenty to cheer for in its positive view of how this is changing), you really feel both Arati's sense of empowerment and the emasculative humiliation Subrata and Priyogopal suffer as a result.

Technically, the film is a subtle wonder to behold. The filmmaking may not be eye-catchingly fancy, but Ray's use of emotional close-ups, locked-on-character dolly shots and beautifully timed edits can't help make you wonder if we've actually moved forward since then, while his use of frame space and depth to locate multiple characters within the Academy ratio and comment on their relationship to each other in the context of the moment is consistently impressive. The film also contains one of the most perfectly realised camera movements I have seen in years, a mid-shot of Arati talking up her husband to an old friend that unexpectedly goes on the move, tracking slowly past her and coming to rest on the concealed Subrata, the cheerful face of Arati's companion faintly reflected in the glossy black pillar situated to his left. There's a sizeable paragraph of meaning that can be read into this scene and the purpose and effectiveness of this shot alone.

Mahanagar is one hell of a film to discover the magic of Satyajit Ray's cinema through, an intelligent, progressive and emotionally compelling drama of changing times and shifting gender roles, and one that is tied neither to its place nor – thanks to its subtle performances and note-perfect direction – its time.

| Charulata / The Lonely Wife (1964) |

|

Even if you know the translation of the Indian title in advance, the opening scene of Charulata has the instant hook of intrigue. A woman who may or may not be the title character breezes quickly through a large house (her movements accentuated by some briskly executed tracking shots), calls a servant into action, and exchanges a book she has been reading for another in a manner that makes it uncertain whether she is doing so surreptitiously. She then takes a pair of binoculars and spies on a man who is making his way down the street outside, moving rapidly from window to window to keep track of his movements. She continues to train the glasses on him as he enters the house and walks past her without even acknowledging her presence, completely lost as he is in the book he is reading. Title aside, it would be difficult to judge their relationship to each other or exactly what's going on, but one of the many things I'm learning about Satyajit Ray as a filmmaker is that every shot and scene and seemingly casual moment he puts in a film is there for a reason, and the thinking behind this opening sequence becomes clear in the scenes that immediately follow.

Set in 1870s Calcutta, the story centres around the title character, known by those close to her as Charu, the beautiful and intelligent wife of political newspaper publisher and editor Bhupati. Bhupati loves his wife but is passionate about his work, which he regards as Cahru's only rival for his devotion. Aware of and concerned for his wife's loneliness, he invites his older brother Umapada and his wife Manda to stay with them, and a short while later the family receive a surprise visit from Bhupati's younger cousin Amal, an aspiring writer with a carefree attitude that Bhupati is looking to curb by seeing him married. Suspecting that Charu has literary aspirations, Bhupati encourages Amal to spend time with her and determine whether she has a talent that is worth nurturing, a process that sees the relationship between the two move beyond that of simple friendship.

The development of the relationship between Charu and Amal is the core of the drama and is handled with the same sort of beguiling but inexplicit suggestiveness that was to characterise Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love 36 years later. A shared interest sparks a bond that grows through a series of innocent encounters and stolen glances that evolve into lingering looks, the suggestion of a love affair that neither party will openly admit to being involved in. There's even a period of jealous hurt when Amal has an essay published before Charu, one he had written in her notebook and promised would remain there. The key scene in this beguiling process sees Amal become lost in the rediscovery of his love of writing as Charu sits on a swing, sings to him and watches him through her binoculars. It's a sequence justifiably celebrated for its technical handling, for the camera that stays locked in close up on Charu and moves with her as she swings and sings directly to the audience (a sequence that is directly referenced in the 2005 Bollywood film Parineeta), for the immaculately framed angle on Amal as Cahru swings in the background, and for Charu's point-of-view shots of the prone figure of Amal as he works on his essay.

Bhupati is never sidelined by Charu and Amal's story, and while in the early stages he is easy to admire for the passion he has for his work and his cheerful anti-government stance, later we get to feel for Bhupati the man as he is effectively betrayed by everyone close to him, whether it be through their actions or their emotions. It's this subtle shift in focus that provides a two-pronged emotional climax to the story, and as Charu weeps in despair and vocally betrays her feelings for Amal, it's the pain of the man who inadvertently witnesses this display that cuts the deepest.

Charulata has been cited – and I can't vouch for this beyond the anecdotal – as Ray's favourite of his own films, the only one he would not make changes to had he the chance to remake his entire oeuvre. Having been so blown away by Mahanagar I was somehow expecting a lesser work, but Charulata matches it at every turn, making each shot and edit count for the characters and the story, particularly the emotionally charged use of close-ups and character-locked camera moves. Like Mahanagar, Charulata is an object lesson in dramatic development and emotional engagement, a beautifully told and ultimately heart-rending story that once again feels in no way locked to a specific place or time.

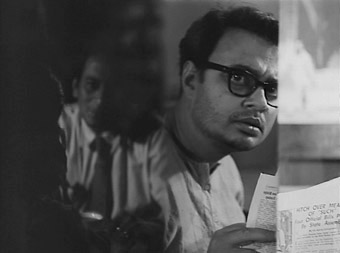

The hero in question is Arindam Mukherjee, one of India's most popular film stars who is so named for the roles that he plays, and he's about to undergo a journey both physical and emotional. As the film opens, he's preparing to depart for Delhi to collect a prestigious award, a journey he elects to do by train when all available flights are booked. Times have obviously changed, as it's hard to imagine a major Bollywood star of today sharing travelling space with the hoi polloi, but being recognised and approached by the public he arrogantly dismisses at the start of the film does not seem to present a problem for him.

Once the journey gets under way, the story focus widens to include a collection of characters worthy of an Agatha Christie murder mystery, strangers on a train destined to interact in ways that could prove quietly life-changing. The first compartment Arindam is offered brings him into polite but immediate confrontation with Aghore Chatterjie, an elderly journalist with an intense dislike of the film industry, and he quickly transfers to the company of a family made up of mildly star-struck Manorama, her unwell and smilingly silent daughter Bulbul, and her successful industrialist husband Haren Bose, another man who holds the film industry and its practitioners in low regard. Also on board are Pritish Sarkar, the owner of a small advertising firm, who with the help of his wife Molly is looking to score a deal with Bose. There's also cheerily upbeat couple Ajoy and Sefalika, and Aditi, young proprietor and publisher of a magazine written exclusive by women. Finally, introduced almost as background detail but remaining a curiously enigmatic presence throughout, is a silent but contented swami who shares a compartment with the Sarkars, who are so wrapped up in their own issues that they hardly even notice his presence.

Ray spends a good half-hour just sketching this characters and allowing them to energetically interact, and he frankly could have spent even longer, so engaging are they and their exchanges. The various reactions to Arindam's presence are of particular interest, from the feverish Bulbul's unbroken gaze to her father's disapproving bluster, dismissing the Indian film industry with the proclamation that "Our motto seems to be produce more and produce rubbish," which elicits the amused reply, "That's why family planning is so important." A short while later it's Bose himself who prompts a smile when he reacts with disbelief to the dining car's limited drinks menu. "Darjeeling is next door," he remarks to the ever-smiling steward, "and you don't serve tea?"

But it's once Arindam gets into conversation with Aditi that the journey's narrative purpose unfolds. Expressing a disinterest in his work and profession, she is nonetheless persuaded of the value to her magazine of an interview with the actor by new friends Ajoy and Sefalika. Arindam politely declines, but later seeks her out precisely because of her lack of interest in him and his work, needing someone to talk to about the bad dreams and unhappy memories that have begun to plague him. In a series of revealing flashbacks, Arindam recalls the people and experiences that first drove him forward and the once-cherished friends who were lost in the wake of his self-centered ambition. Although not as instantly engaging as the inter-character banter, the flashbacks – of which there are several in succession – nonetheless prove to be the heart of the movie, positive experiences tainted by regret that collectively paint a portrait of a man who is increasingly aware of the moral and personal price he has paid for his success. Aditi initially adopts her role of patient listener in order to secretly make notes for the exclusive article she now plans to write, a process she all but abandons as she and we begin to understand and sympathise with the man beneath the movie star persona.

Regarded as a lesser Ray work by some (and by that I mean it's seen as a very fine film rather than a great one), Nayak may not quite hit the dramatic heights of Mahanagar and Charulata, but it's still a compelling, sensitive and impeccably made work, one whose lively collection of secondary characters and sub-plots are worth the admission price alone. And I may be new to Ray's cinema, but I'm guessing that there aren't too many in his cannon that can boast a vividly realised dream sequence in which the dreamer finds himself terrorised by skeletal arms growing from a landscape of bank notes.

Well, there's good and not so good news here. The good is that, save for the odd scratch and a few end-of-reel dust spots, the prints are largely clean, the detail is generally clear, and the contrast, though variable in place and strong enough on occasion to swallow up the shadow detail, is largely pleasing. Charulata appears to have suffered the most over the years, having more dust and scratches, the odd bit of frame jitter, and a few shots whose sharpness has slipped a little, but it's still very watchable. However, all three films are NTSC to PAL conversions and this is quite visible at times, with judders on some fast movements of characters or camera, a very slight softness to the picture on all three films (at least on a large screen – this notices considerably less on a smaller TV) and some giveaway diagonal jaggies and fine detail definition issues. Upscaling the DVDs to a large high-def screen does tend to exaggerate these issues further. The quality of the films themselves means that it's surprisingly easy to ignore this for much of the time, but it's still a shame that true PAL or HD masters weren't available for this set.

The limited dynamic range of the soundtracks betrays the age of all three films, and once again it's Charulata that comes off worst here, with a background crackle that gets a little boisterous at some of the reel changes. Nayak is free of this, but there were clearly some sound recording issues at a couple of the locations, where room acoustics on wide shots affect the volume and clarity of the dialogue.

Only the same brief biography of Ray on all three discs.

One of the small advantages of coming late to a great director's oeuvre is that you know there's plenty more material out there just waiting for that always special first viewing experience. As an introduction to the cinema of Satyajit Ray, this three-film set is a terrific collection that should win anyone over, and certainly has me fired up for volume 2. Existing Ray fans may find their delight at seeing the films released on UK DVD tempered a little by the NTSC to PAL conversions.

|