| |

This natural thing, work, this thing which/Makes humanity a force of nature, work/This thing like swimming in water/like eating meat/This thing like mating, like singing/It has had a bad press through the long centuries and/Into our own times. |

| |

Bertolt Brecht |

| |

The world might have been a stage for Shakespeare but to me it is a kitchen, where people come and go and cannot stay long enough to understand each other, and friendships, loves and enmities are forgotten as quickly as they are made. The quality of the food is not so important as the speed with which it is served. |

| |

Arnold Wesker, Introduction to The Kitchen |

There is a deliciously funny passage in Vincenzo Latronico’s novel Perfection that mocks a millennial couple for their obsession with food. Hey, you may say, who doesn’t like and need food? Latronico, though, targets an aggravated consumption divorced from the basic human need for sustenance. As students, Anna and Tom made ‘salty, stodgy meals, high in calories, and all the same reddish-brown colour’. Then, suddenly, without knowing when and how it had all begun, they found themselves spending inordinate amounts of time, mental energy and money on their new-found passion. ‘Kholrabi and trombetta zucchini and greenish-yellow heirloom tomatoes would be sliced into impossibly thin slivers or rustic chunks on thick butcher’s blocks. Their preferred knives were first ceramic, then rusty Vietnamese steel, then forged stainless steel.’

It wasn’t consumerism that drove them, you understand, and their interest in food hadn’t been planted by sly marketers, oh no. ‘It was a part of their quest for freedom and pleasure – the pleasure of eating chiefly, but also the tactile pleasure of cooking slowly, and the visual pleasure afforded by the perfect plating. All their friends shared this interest. Mysteriously enough, they had discovered home-made fermentation kits, fire-roasted cauliflower and umami at exactly the same time . . . They were all learning together. Food was part of their culture, and they would discuss it among themselves in the same way previous generations had discussed films, books and politics. It helped define who they were.’

This pervasive cultural phenomenon is as hard to pin down as dumbing down and as difficult to counter. Although food culture currently enjoys a ludicrously elevated status, in certain circles, in certain overconsuming countries, few films have highlighted the ways the reciprocal exchange of cuisines can counter prejudice and encourage human solidarity. In 1987, Gabriel Axel’s delightfully delicate Babette’s Feast and John Sayles’ magisterial Matewan both did so: in the former, a gifted French chef overcomes the repressive puritanism of a Danish conventicle; in the latter, Italians drafted in as scab labour make common cause with striking miners over their campfires and the sharing of ingredients and recipes. Films that reveal the high human and creature costs of industrial food production are even rarer. Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s Our Daily Bread (2005), David Romero’s The Kitchenistas (2021), and Michael Sarnoski’s Pig (2021) merit honourable mention.

More generally, films focused on food have tended toward the darkly satirical, deploying kitchens and restaurants as the settings from which to deliver disgusted rebukes to pigs-at-a-trough bourgeois gluttony and greed. Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe (1973), Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), and Mark Mylod’s The Menu (2022) all gleefully adopt the latter approach to telling effect. Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022) also deploys food as a metaphor for avarice but shifts the locus of rapacity to a luxury yacht. As Östlund reveals the cracks in a relationship tested to breaking point when the ship sinks, he also probes those apparent in the no less fraught relations between the privileged passengers and overtaxed crew.

Alonso Ruizpalacios’ pulsing, propulsive fourth feature, La cocina, tells a more nuanced tale of love under difficult circumstances while focusing on those who prepare and serve food in mid-range restaurants. Epicureans, gastronomists, gourmets and locavores need not apply. Nor need they worry: the acclaimed Mexican writer-director is less interested in excoriating delinquent over-consumers than in examining the exploitation of immigrant workers and, if to a lesser extent, of their predominantly white, comparatively privileged serving colleagues.

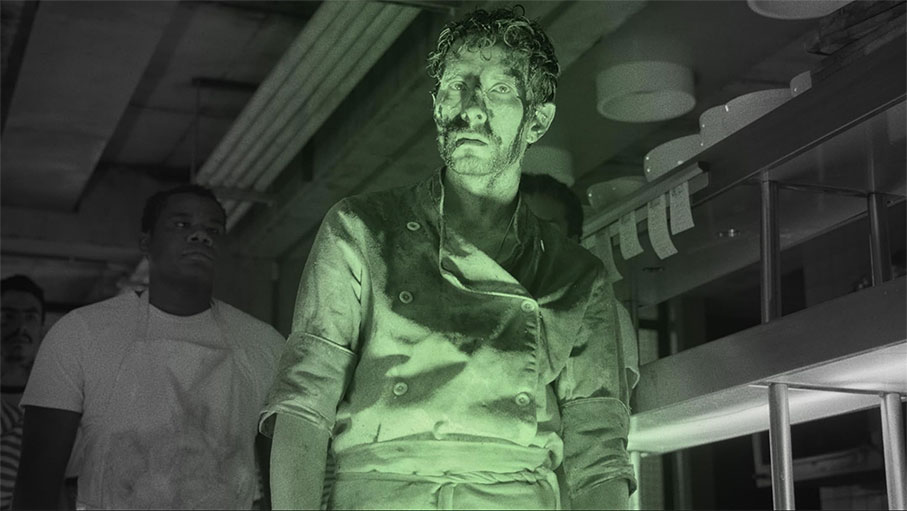

Shot in limpid black & white (though enhanced by flashes of green), La cocina takes us behind the swing doors of The Grill, a fast-food restaurant on or just off New York’s Times Square tourist trap. Ruizpalacios drops us deep into the labyrinthine subterranean complex where the fast, frenzied hard work is done – by largely undocumented Latino and Latina kitchen staff pushed to the edge of sanity by the threat of deportation as well as the impossible pace of their work.

The film opens with a quote from Thoreau’s essay Life Without Principle: ‘The world is a place of business. What an infinite bustle! I am awakened almost every night by the panting of the locomotive. It interrupts my dreams.’ La cocina continues at a gentle pace with a collage composed of slow-motion footage of the Staten Island ferry and still images of rough sleepers on Times Square. Picking up the thread of thwarted dreams, we follow a Mexican immigrant, Estela (Anna Diaz), as she makes her way to The Grill in search of work. She secures an interview with middle-manager Luis (Eduardo Olmos) by stealth and, thanks to fortuitous staff shortages and connections from back home, is immediately thrown into the fray. Once in the kitchen Estela must live on her wits and find her feet unaided by those buzzing around her – for while the kitchen can only function when the cogs in the machine work together, it is also a dog-eat-dog world of lone struggle and zealously guarded, colliding fiefdoms .

As the orders pile up during the lunchtime rush and the swirling chaos of the kitchen spirals out of control, sous chef Pedro (Raúl Briones) and his girlfriend, waitress Julia (Rooney Mara), seek (often erotic) solace in one another. Although Julia is carrying his child, Pedro reluctantly provides the $800 she needs for an abortion. Meanwhile, the conflicts, prejudices and tensions of the kitchen are intensified when takings of $832 go missing. We are drawn into the growing atmosphere of suspicion when an investigation into the missing money throws yet more fat on the frying pan. A flood caused by a faulty drinks machine swells the rising tide of stress and suggests that The Grill – symbol of the rapacious, remorseless soul-destroying machine of capitalism – is a sinking ship.

Although La cocina is noisy and thrillingly kinetic, Ruizpalacios sensibly concedes us pause for breath and thought during a central scene of quiet lyrical reflection. When the midday surge subsides, beer and cigarettes are shared in the back alley where the kitchen waste piles up. Pedro challenges four of his colleagues to share their dreams too. When his turn comes around, eloquent Nonzo (Motell Gyn Foster) tells the enigmatic tale of a migrating Neapolitan mariner aided by a mysterious burst of green light. Is this the elusive light of maritime legend, said to shoot out hope when the sun sinks behind the horizon and featured in Tacita Dean’s The Green Ray (2001)? Be that as it may, it appears to Nonzo’s Neapolitan twice and it will appear again late on in La cocina.

Rooney Mara, an elfin-faced modern day Mia Farrow, plays Julia as a streetwise battler who hides her vulnerability behind a façade of facial steel and a smokescreen of rapid-fire tough talk. By granting Julia agency, Ruizpalacios champions pro-choice rights and challenges those who would force ‘the unwilling to bear the unwanted.’ Elsewhere, he allows for moments of rare masculine tenderness. At one point Pedro uses a hoja santa leaf from his mother’s garden in Puebla to lovingly craft a lunch for Julia. In another scene, tears fall from his eyes as he contemplates losing her. Such moments reveal a gentler, softer side to Pedro – a volcanic ball of fire habitually on an even shorter fuse than his equally hard-pressed co-workers. His nervous effervescence is, it must be said, unsurprising given that his dreams of a son, a life with Julia, and a coveted green card hang precariously in the balance and, ultimately, vanish before his ineffably sad, salt-stung eyes.

Wired up like a coiled spring, Pedro clashes with the loud-mouthed bullnecked head chef (Lee Sellars) – who places him on a three-strikes-and-you’re-out warning. He also locks horns with Max (Spenser Granese) – the monoglot bigot of a steak chef who screams ‘Speak English’ when his multilingual colleagues joyously trade salty insults in Arabic, Spanish and French. Pedro steadily works his way through his warnings and, as the film lurches to its cataclysmic conclusion, he finally, inevitably, snaps.

Pedro smashes the machine that spews out orders, invoking Mario Savio’s famous Free Speech Movement speech: ‘There comes a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!’

The Grill’s owner, Rashid (Oded Fehr), is as baffled as he is appalled by Pedro’s actions. ‘You have stopped my world’, he screams, ‘Why?’ He then goes to the nub of the matter by asking what more the workers want than to be fed and paid? Ruizpalacios directs that question at us. He invites us to think through the unpalatable gap between working and living; between the anomie, alienation and hollowness of modern life and the different, better world we might create. The chasm separating customers and consumers on the one hand, wage earners and workers on the other is implicit in every frame of the film.

If the film can seem melodramatic and theatrical, so too can working life in kitchens. If the film often appears messy, that’s because kitchens are messy. If characters drift in and out of focus, that’s because they do in kitchens too. If the acting occasionally appears overwrought, that’s because overworked kitchen staff tend to be overwrought too. For all its nominal imperfections, La cocina has more heart and soul than a thousand bang-bang thrillers or oh-my-sir-you-make-me-blush period dramas. Ruizpalacios’ laudable anger at society’s contemptuous treatment of those who do our dirty work, put food on our plates, and keep our cities running ensures that we, too, side with the underdogs.

As the racist rhetoric of populist right-wing parties takes hold across Europe and the States and scapegoating of ‘the other’ becomes enshrined as government policy, La cocina could not be timelier. It is squarely on the side of the precariat, those forced to flee their native lands and work in the gig economy, those demonised by Donald Trump’s cruel and bigoted campaign of deportation and harassment. It joins a growing body of extraordinary contemporary films that highlight the migrant experience: Pawel Pawlikowski’s Last Resort (2000), Tom McCarthy’s The Visitor (2007), Ben Sharrock’s Limbo (2020), Sally El Hosaini’s The Swimmers (2022), Agnieska Holland’s Green Borders (2023), and Laura Carriera’s On Falling (2024), to name but a few.

Essential though such interventions are, La cocina does something perhaps even more daring and urgent than to demand dignity for an abject and marginalised immigrant underclass. It dares us to dream of a world where work and play exist as one, even of a world without work. It insists that neither history nor the history of toil have ended, reminds us that work is deliberately and disastrously under-represented in the dominant culture, and asks why that might be the case.

Nanni Moretti’s Aprile (1998) ends with a beginning – in a kitchen. Torn between his urge to document contemporary Italian politics and his desire to make a kitsch 1950’s musical about a Leftist pastry chef, Moretti dithers until the film’s final sequence. In the musical that finally begins just before the credits roll, the staff of Moretti’s kitchen shimmy and sway to the joyful strains of Yma Sumac’s ‘Bo Mambo’. Their pristine white aprons contrast with the bold colours of their gingham uniforms and of the food they are preparing. It is work, but not as we know it, yet.

The contrast between Moretti’s playful closing flourish in Aprile and Ruizpalacios’ judicious use of neo-realist black and white in La Cocina could not be greater. The Italian maestro and his Mexican counterpart, though, share a commitment to recording contemporary political realities aligned with a desire to see workaday drudgery infused with play. And Ruizpalacios, also ends with a beginning – in a kitchen. Pedro burns his bridges in The Grill, but we feel sure that his energy and spunk will ensure he makes a fresh start, with or without Julia.

Ruizpalacios’ decision to shoot in black and white and La cocina’s muted monochrome tones create an atemporal atmosphere reminiscent of Alfonso Cuarón’s Oscar-winner Roma (2018). Both films are Mexican masterclasses in slow-burn brio. It feels as if Ruizpalcios is sifting the past (particularly his own) to see what lessons might be learned there – as Cuarón did in Roma, Guillermo del Toro did in Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and Alejandro González Iñárritu did in Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths (2022). Ruizpalacios and the Three Amigos certainly exchange ideas and influences so they often pull in the same direction.

Introducing a recent BFI retrospective of Alain Tanner’s brilliant work that he himself curated, Cuarón spoke of its huge impact on his filmmaking friends. In Charles, Dead or Alive (1969), Salamander (1971) and Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (1976, co-directed with John Berger) Tanner sifted through the wreckage of May ’68 and asked how we might best respond to the disenchantment of seeing history move in the wrong direction. Cuarón, who named his first son ‘Jonah’ in honour of Berger and Tanner’s film, also spoke of Tanner’s conviction that the apparent collapse of the big dreams can generate a new radical politics based on small everyday actions, disobedience and individual acts of resistance. Cuarón stressed Tanner’s belief that work, play and politics can and should be combined – as Christopher Zalla does in Radical (2024), which owes an obvious debt to Berger and Tanner’s Jonah. Films beget films and initiate interesting conversations across time.

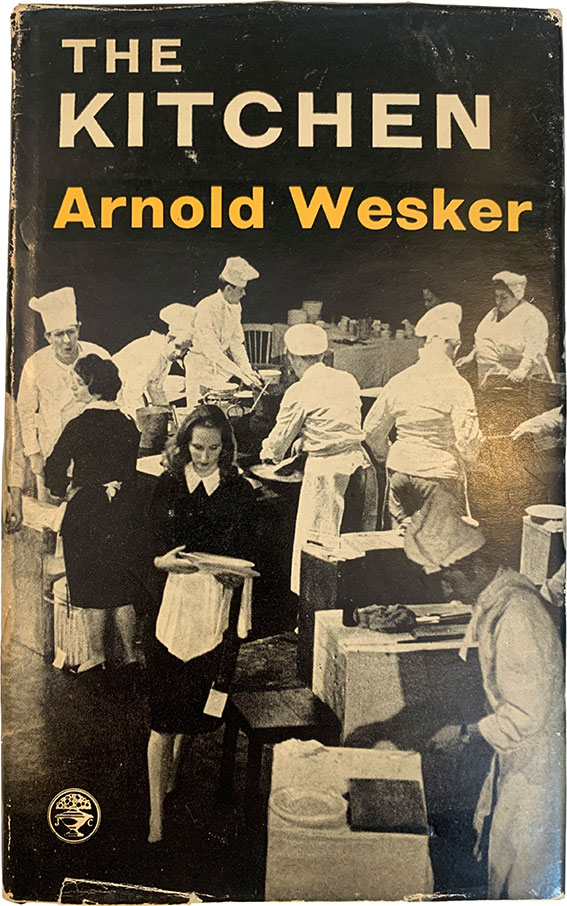

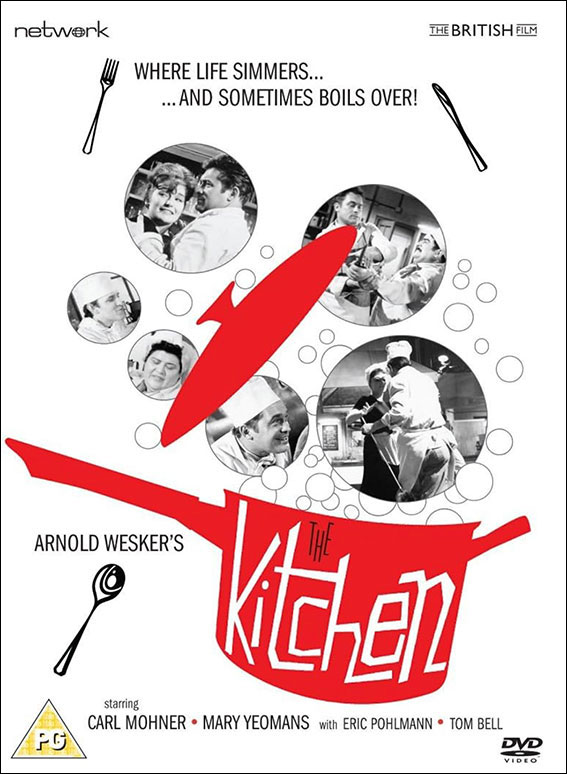

La cocina is raised to great heights by Juan Pablo Ramírez’s restless camera and elegant cinematography; by the mesmerizing performances of Briones, Mara and the entire ensemble cast; and by the agile, expertly executed choreography that steers the 20-odd actors through a confined space with seemingly effortless ease. The film owes its greatest debt, though, to its script and the source text – Wesker’s The Kitchen. Ruizpalacios graciously acknowledges the importance of the play to his film by granting Wesker equal writing credits. He follows Wesker’s lead by inserting a meditative interlude into La cocina, much of the film’s dialogue is transferred verbatim from the play into the film – the thematic concerns and stylistic panache of which mirror Wesker’s. A word about that groundbreaking work, therefore, seems appropriate.

Ruizpalacios discovered Wesker’s The Kitchen during his days as a student at RADA. Not long arrived in London from Mexico at the time, he supported himself with a string of menial jobs (the dread phrase ‘the gig economy’ had not yet been coined). One such was in the Rainforest Café, a long-defunct West End restaurant not dissimilar to The Grill, and he says Wesker’s text helped him through a dispiriting time there. Clearly that experience stayed with him down the years and he shares a few of the valuable life lessons it taught him in La cocina.

Nobody better understood Wesker’s intentions than the legendary critic Kenneth Tynan. Reviewing the play in the Observer, Tynan said: ‘The thronged, clangorous, ill-ventilated kitchen in which Mr Wesker’s play takes place is a metaphor for the dehumanising world of commercialism and mass-production. The Kitchen achieves something that few playwrights have ever attempted: it dramatises work.’

When the play opened at the Royal Court in 1959, Wesker was immediately labelled an ‘angry young man’, but then so was every male playwright even remotely critical of the moribund class relations that disfigured Britain in the late 50s and early 60s. The ‘angry young men’, of course, were neither particularly angry or young. Their anger, such as it was; arising largely from an embattled, fragile and unstable masculinity as it did; was often directed against women. No mention was made of ‘angry young women’ back then – despite the best efforts of Shelagh Delaney, Anne Jellicoe, Doris Lessing and others. And despite much fashionable talk of ‘kitchen sink realism’ and ‘gritty’ representations of working-class life, an equally loud silence surrounded the world of work.

Prior to Wesker’s play and James Hill’s 1961 film adaptation of it, the thing most people did most often remained eerily absent from stage and screen. Arthur Seaton might have worked a lathe in a factory, but the focus of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) was squarely on the weekend not the working week, on consumption rather than production, on leisure not labour – a metaphorical distance from the lived experience of working people coupled to the geographical one helpfully highlighted in John Krish’s phrase ‘That Long Shot of Our Town from That Hill’.

Then as now, middle class actors and directors called the shots. If the supremely talented, criminally underrated James Bell brought his working-class experience to The Kitchen, and Albert Finney brought his lower middle-class experience to Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, they remained the exceptions that proved the rule – at least until later in the sixties, when social mobility and the pop aristocracy shifted the goal posts. It is, nonetheless, impossible not to look back nostalgically to a period when working-class men and women forced their way into the cultural industries and introduced their accents and (aspects of) their lived experiences into the wider culture.

Since then, associational cultures and class solidarity have largely collapsed due to deindustrialisation, systematic assaults on organised labour, homogenising consumerism, rampant individualism, sharp elbows and so on, but there has seldom been a greater need for collective cultural and political resistance to spiralling local and global inequality. Nor has there ever been a greater need for neo-situationist individual action to reclaim our lives from the boredom and monotony of McJobs.

Call it what you will – cannibal, choke point, crony, extractive, gangster, monopoly, surveillance, hyper, late or post capitalism; the spectacle or the machine, market Stalinism or techno-feudalism, if you prefer – the dominant dispensation continues to rob those of us who work for a living blind. They do so partly by reducing work to deadening routine, partly by hiding work away as a guilty secret. Excising waged labour from screens small and silver has always benefitted those happy to portray millions of us simultaneously as work-shy benefit thieves and happy shoppers.

Such ideological slop has been compounded by the capture of culture and the commanding heights of the economy, hell, even our capacity for independent thought by Big Business, Big Pharma, Big Oil and Big Tech. The staggering shift of wealth and power from labour to capital facilitated by neoliberalism since Wesker’s heyday has ensured that cameras and keyboards are increasingly placed at the service of elites. Today, despite tokenistic attempts to increase class diversity in the cultural sector, nepo babies and undeserving rich kids supported by the Bank of Mummy & Daddy still predominate. Our culture consequently reflects their concerns.

La cocina discredits that sorry situation and goes some way to correcting an imbalance that disfigures our culture and delimits our capacity to dream. This angry, tender-hearted, cumulatively moving tour de force shows us what dehumanising, low-waged, precarious work looks like while challenging us to imagine how fulfilling, enjoyable and creative work could be. Arising from its director’s own experience of service industry work, created by a cast and crew as diverse as its protagonists, La cocina is an exhilarating, often heart-stopping white-knuckle ride through the lives of others that provides us with nourishing food for thought and leaves us crying out for more.

|