“The epic is concerned with narrative structure not

decoration. Decoration is bourgeois.” |

Lindsay Anderson |

"The head, heart and hairy area below the stomach

is what should be stimulated by cinema." |

George Kuchar |

A fortnight after watching The Deep Blue Sea screened as the Closing Night Gala of the London Film Festival, I had the pleasure of seeing Terence Davies deliver the Colin Young Emeritus Lecture at the National Film & Television School's 40th Anniversary Celebration. The annual lecture, traditionally given by graduates of the NFTS, has previously been delivered by the likes of Nick Broomfield and David Puttnam. I had expected Davies, as the man-of-the-moment, to talk solemnly about his new film. The Deep Blue Sea is, after all, Davies's first fiction feature since The House of Mirth in 2000. I had also hoped that he might say something about the industry in which he works, from time to time, perhaps even have a dig at those who'd denied him work. Boy, was I in for a surprise. Davies delivered a lecture like no other. Mischievously tearing up the rulebook, he had his startled audience in stitches with a series of clips from a few of his favourite films: Carry on Nurse, Gypsy, Oaklahoma!, The Pajama Game and Sweet Charity. Davies's unorthodox 'lecture', billed under the heading 'Always the Bridesmaid', was subtitled: 'Some of Cinema's Greatest Moments were Created by People Who Did One Great Turn before Slipping from the Limelight'.

The extracts eloquently made Davies's point for him. After watching Rita Shaw and Eddie Foy Junior's "I'll Never be Jealous Again" duet from The Pajama Game, Paul Wallace's effortlessly elegant dancing in Gypsy, and Faith Dane's unforgettable turn as Miss Mazeppa in the same film ("If you wanna stump it, bump it with a trumpet!"), it was impossible not to wonder why these abundantly talented actors didn't work more often thereafter. I also wondered if Davies wasn't having a dig after all. Although each of the clips had an irresistible zip and a zing, it was Davies's infectious enthusiasm ("Isn't that just sublime!") that made the evening so hugely enjoyable. He had the audience in the palm of his hand. Fittingly, he concluded his 'address' with the uproariously funny 'You Gotta to Have a Gimmick' scene from Gypsy, in which innocent Natalie Wood, as young Gypsy Lee Rose, is given a comic lecture in the art of stripping by three sassy burlesque dancers, by which time tears of laughter were streaming down our faces. It made me want to watch musicals, by Terence Davies.

Still smiling inside after the event, I asked Colin Young himself, who founded the NFTS in 1971, what he'd made of Davies's lecture. He said: "Well, it was a breath of fresh air wasn't it?" He paused, then, moving his grouped forefingers back and forth against his thumb in the universal gesture for inconsequential chatter, said: "Better than all that yakety-yak!" Much as I enjoyed the evening, I'm not so sure it was. There's a time for ribald entertainment and for cocking a snook at humourless puritans; a time and a place, too, for serious-minded argument delivered without a smile on its face. I was reminded of another surprising occasion when I'd hoped for more or, at least, something else from Davies. In early 2007, during a retrospective of Davies's work, I attended an NFT1 screening of Distant Voices, Still Lives – one of the greatest films ever made, full stop – after which he received a standing ovation from a full house and the British Film Institute's highest honour: a BFI Fellowship. He hadn't made a film for eight years at the time and, again, I'd hoped he'd let off steam about film financing and philistinism. Instead, he recited John Betjeman's gymkhana poem 'Hunter Trials', in the manner of Joyce Grenfell ("Oh wasn't it naughty of Smudges?/Oh Mummy, I'm sick with disgust/She threw me in front of the judges/And my silly old collarbone's bust.").

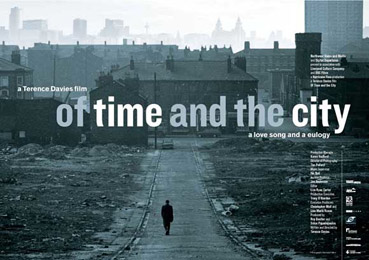

I'd intended to ask Davies why he'd decided to handle those occasions as he had. When we chatted after the NFTS event, I steered him into conversation about Humphrey Jennings in the hope of establishing a platform for my question. No sooner had Davies acknowledged Jennings's influence on his last film, Of Time and the City, and categorically refuted my suggestion that Jennings might have prompted the idea for a certain scene in his latest, than he was whisked off. Those two occasions, therefore, remain a puzzle to me. Why would this articulate, intelligent, often outspoken director, the man who once told me that he reads TS Eliot's Four Quartets every day, opt to play the court jester at the very moment when seriousness was expected? For the sheer mischievous fun of it, of course, and because he has the autodidact's irresistible urge to defy convention, perhaps also to remind us, as his early work does, that our nominally transient cultural memories remain real long after more seemingly serious ones fade. Whether or not this was Davies's way of insisting on equality between 'individual' and 'imposed' time, he certainly appreciates more than most that popular culture marks time for us, and that cinema contains time present, past and future as surely as TS Eliot's Burnt Norton; which is why his special fondness for the past is particularly curious.

Whatever the reasons for his approach to those public events, those nights seemed to hint at Davies's crowd-pleasing propensities and his reluctance to be typecast as the poet of emotional violence and dark realities. It is as if a voice in his mind occasionally whispers, "Oh Terence, for god's sake, lighten up!" Those occasions also highlight the eclecticism of Davies's enthusiasms, his democratic irreverence and endearing sense of humour, his vacillation between popular and highbrow culture, and his camp love of a certain cinema of the past. As we shall see, that last characteristic sits comfortably with his preference for the past over the present, and has shaped his handling of The Deep Blue Sea, to the film's detriment.

Terence Davies's output has been famously sparse. Since finishing his autobiographical Trilogy in 1983, the 67-year-old auteur has made just five features. Two majestic films further exploring his experiences of growing up in Liverpool in the '40's and '50's – Distance Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992) – were followed by two polished adaptations of American novels – of John Kennedy Toole's The Neon Bible (1995), and Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth (2000). In his magnificent documentary about Liverpool, Of Time and the City (2008), Davies returned to the scenes and the subject of his childhood. Now, in The Deep Blue Sea, he is back in the '40s and '50s again, for another adaptation, of Terence Rattigan's 1952 play.

The past, then, has been a recurring theme throughout Davies's career, and it has served him and his audiences well – until now. In his latest film, funded by Film Four and the recently abolished Film Council, he takes several misguided steps too far in that direction. Contemporary audiences with modern sensibilities cannot follow him. As we would expect given Davies's track record, the film is stylishly shot and precisely composed. Unfortunately, despite and because of the accuracy with which Davies recreates the mood, mores and manners of post-war English life, The Deep Blue Sea lacks depth. It is beautiful, but unruffled and flat.

Before we look at how and why the film fails, and what its way of focusing on the past implies, I should stress that I approach Terence Davies with the deepest respect and will talk about the film with my heart in my mouth. Davies has more talent in his left finger alone than most directors possess, tout court. No film he makes could be less than intelligent, elegant and stimulating. Watching a Terence Davies film screened in the cinema, even one as flawed as this, will always be an experience infinitely more rewarding than that of watching the vast majority of programmes that issue from our televisions. It seems to me, though, that to damn his film with faint praise would be an act of disrespect, not only to his extraordinary gifts as a filmmaker, but to cinema itself. He has earned our undivided attention and we owe it to him to consider his work with the same honest rigour and attention to detail with which he approaches his craft. Ok, but?

Commissioned by The Terence Rattigan Trust as part of the celebration of the playwright's centenary year, the film is twisted out of shape by Davies's understandable desire to remain faithful to the spirit of Rattigan and his times. In adapting Rattigan's tale of marital infidelity with such respectful fidelity, Davies presents values at odds with ours. He also subsumes his own distinctive voice beneath Rattigan's. The Trust gave Davies carte blanche to handle Rattigan's script as he saw fit, even exhorting him to be "radical" with it. The film occasionally flares into life when he takes them at their word and roughs the play up, but he is too respectful of Rattigan to 'betray' the source material, transform it, and update it for our benefit. He opts, instead, to reproduce Rattigan's play much as Anatole Litvak did in his stagey 1955 cinemascope adaptation. Davies brilliantly recreates the stifling social circumstances and claustrophobic values of Rattigan's day – as if the Angry Young Men, Free Cinema, the British New Wave, Second Wave Feminism and the Swinging Sixties hadn't happened in the interim. Rattigan's portrayal of the repressed emotions, suppressed sexuality, stiff upper lips and clipped accents of the bourgeoisie no longer speaks to us, nor, therefore, does The Deep Blue Sea. It is rooted in a sanitized, nostaligic version of the past, and buried beneath mulchy layers of it.

Rattigan's play and Davies's film examine the vapid marriage of a vivacious woman, Lady Hester Collyer (Rachel Weisz), and a stuffy High Court judge, Sir William Collyer (Simon Russell Beale). That marriage unravels when Hester falls head over heels into a disastrous affair with rakish former RAF fighter pilot Freddie Page (Tom Hiddleston). The film opens with Hester's attempted suicide, then tells the story of her doomed relationship with Freddie through a series of flashbacks. The deck is stacked against transgressive love from the outset. Throughout the film we remain trapped within a conventional morality tale in which a woman's refusal of constraints is penalized. Careful girls, it's dangerous out there. Stay safely at home with hubby. Stand by your man. Hester and Sir William are both admirable in their different ways: in striving for freedom outside her stultifying marriage Hester shows great courage in defying bourgeois morality, while poor, rich cuckolded Sir William is compassionate and kindly to the end. Freddie, though, is an immature cad whose incapacity to reciprocate Hester's intense feelings precipitates her suicide attempt, his response to which is, at first, piqued indifference, then callous anger.

Dislike of characters must, of course, be separated away from disapproval of poor or flawed performances. The problem with the film lies primarily in the source material, but also in the miscasting of the actors and misdirection of them. Critical responses to actors are all too often inextricable from subjective judgements on their physical appearance; in this case, although the two leads look the part, the performances they were directed to deliver fall short. This is a failing in the film that flows from Davies's decision to adapt the play as a comment on Rattigan's time not ours. Again, it is the past that interests him most; more, here, than people do. Adrian Mitchell's dictum, "Most people aren't interested in poetry because most poetry isn't interested in most people," can usefully be applied to The Deep Blue Sea. This is doubly disappointing because, in Terence Davies's case, there is no need to substitute the word 'poetry' with the word 'film', because he has previously been interested in most people, and because his earlier films, ironically the autobiographical ones in particular, spoke to us with particular force and directness.

| Project, darling, project! |

|

Rachel Weisz, in the central role, treads cautiously as she follows in the footsteps of greatness. Actresses as impressive as Peggy Ashcroft, Virginia McKenna, Harriet Walter and Penelope Wilton have played the part of Hester on stage. The great Marlene Dietrich turned the role down when she was approached by Anatole Litvak, feeling that she couldn't be convincing as a woman prepared to gas herself because unable either to keep her lover or replace him. For the German-born actress considering the role in the immediate post-war years, the connotations of a death by gas might have raised certain moral questions too! The part would, ultimately, be accepted and (over)acted by Vivien Leigh. She intensely disliked her own theatrical performance opposite an ill-cast Kenneth More, who had earlier played Freddie to Peggy Ashcroft's Hester on stage.

Weisz, thankfully, plays it straight. She walks through the film, aptly, as if in a daze, her pallid face always seeming startled by the feelings that have taken possession of her. Sadly, she also plays Hester as if scared of those same feelings herself; with such reserve, in fact, that the character's inner turmoil seldom surfaces. Leigh, at least, tapped into the madness inherent in desperate, obsessive love. Weisz is no Vivienne Leigh and definitely no Dietrich – How could she be? Why should she be? – but she is a talented actress who always gives of her best. If she rarely convinces us that her world has been turned inside out and upside down, she seldom puts a foot wrong either. It feels as if she is doing her professional utmost to please, but doesn't quite believe in Davies's take on Hester, particularly his emphasis on restraint at the expense of passion. She is imprisoned in the straitjacket of the play as surely as Davies is, because Davies is.

It isn't as if Davies is too much the aesthete to show us the messy, mad truth of relationships like this. He has never shied from dark truths before. Here, though, his approach to Rattigan stifles his better instincts. One early moment in the film forewarns us of the ascetic, bloodless fare that follows. After her attempted suicide, her life in ruins, her lungs full of gas and bile, Hester vomits. She does so with such prim delicacy that the credibility of the sequence and all that follows is ruined. Viewing the film through modern, post-feminist eyes, we can admire Hester's determination to satisfy the urges and appetites unfulfilled in her sexless marriage, but we baulk, as Dietrich did, at the depths of her self-destructive, supine surrender. What's more, we cannot believe that Hester would surrender to a man such as Freddie; a man who, as played by Hiddlestone, is more Biggles than Rhett Butler. This is, moreover, a stiff Biggles in a stuffed, starched shirt that only softens when conditioned by feelings of loss and remorse at the film's finale. Hiddlestone, like Weisz, is an accomplished actor with the prerequisite technical skills, as well as the obligatory high cheekbones and perfect teeth. Although Vivienne Leigh and Kenneth Moore set a high, if hammy standard in Litvak's version, the contemporary duo more than match their cinematic predecessors. They bring subtlety and understanding to certain scenes, notably the perfectly performed one prior to Freddie's final flight from Hester. There Hiddlestone unbuttons and Weisz unravels. Generally, however, Hiddlestone and Weisz lack either the depth or capacity for abandon necessary to convincingly portray the unhinged passion and incontinent emotion implied in the scripts.

They are not well served by dialogue that often verges on the comical. At one point Hester tells her husband, "I knew in that tiny moment that I had no power to resist him. No power at all." Elsewhere, Fweddie tells Hester, "I served in the Battle of Britain, old fruit, old darling." Chocs away Biggles! The love scenes, too, the first Davies has directed, are typical of the film's aesthetic: they are polished, tasteful, and anodyne. We must be grateful that Davies eschewed the Hollywood cliché in which mating couples reel against the nearest available wall before disrobing one another feverishly and formulaically, but, as we watch that scene we are all too aware that Davies is a celibate gay man who has lived alone for 30 years, and can't help wondering if this wasn't a leap in the dark for him. That sounds snippy, even facetious, but it needs saying. It may have made a difference. Then again, it might have made none. Directors don't always walk at their tallest when they tread familiar ground. Alexander McKendrick, a fusty Calvanist Scot, went to New York and made Sweet Smell of Success, one of the hippest, most knowing films ever made about sleazy urban amorality. You don't have to go to the Arctic to know it's cold there. Be that as it may, the blame for the absence of any simmering or sizzling carnal chemistry between the two leads cannot be laid at their bare feet alone.

The Deep Blue Sea is a tale of raw love and lust, so among the questions that must define it as a success or failure are the pedestrian ones: does it excite and move us? It doesn't. This is partly because neither Rattigan nor Davies give us any lead-in to Hester's infatuation. There is a lacuna in the film that overrides subjective objections about the actors: we see nothing of love's first flush, nothing of the delirious dance of mutual attraction. We are dropped into the relationship not as it explodes into life, but as it dies. It is hard for us to believe that a man as emotionally immature, bovine and fettered as Freddie could so completely conquer a woman as worldly, beautiful and bright as Hester. It is impossible for us to believe that a woman as superficially demure and self-possessed as her could be swept up by oceanic erotic euphoria. Thousands will doubtless argue that Freddie's dashing good looks, not to mention Sir William's asexuality or homosexuality, would be reason enough for Hester's excited surrender to him. We don't feel her excitement though.

| Music and minor characters |

|

Tellingly, the film's most memorable moments feature the minor characters. If there are question marks over the casting of Hiddlestone and Weisz, the actors who play the minor roles beg the question, 'Who on earth could have done better?' Barbara Jefford as Sir William's mother, Mrs Collyer; Ann Mitchell as Hester's landlady, Mrs Elton; and Sarah Kants as Hester's friend, Liz Jackson, are superb. They not only look the part, they make the parts their own. Although, Simon Russell Beale is equally brilliant as bewhiskered, bewildered Sir William, the film only really comes to life when the minor characters step forward to deliver a visceral honesty missing in the delineation of the central characters. One riveting scene shows Hester and Sir William taking tea with his poisonous mother. The judge is revealed to be a little boy lost, a Mummy's boy deep down, when he sheepishly asks: "Will you be going to Wimbledon this year mother?" He cannot intervene in the tense verbal fencing match between the two women. He can but watch as they circle each other in combative conversation, jabbing ("Oh, you've put the milk in first") and parrying, before the venomous mother strikes, delivering a viperous line that articulates the restraints Hester revolts against. She warns Hester: "Beware of passion. It always leads to something ugly." It is the defining line in the film, not least because Davies's treatment of Rattigan and direction of his leads hint that he himself has taken that warning to heart.

These days, you'd hope, Hester would just tell Mrs Collyer to fuck right off, but Davies is too determined to honour Rattigan, and, to a lesser extent, David Lean's 1945 tearjerker Brief Encounter, to allow us that satisfaction. Lean's classic is cited twice, firstly when Hester and her husband sit opposite each other in their lounge, just like the Hammonds; then again in the cliff-hanging moment when Hester hovers on the Tube platform edge, contemplating suicide a second time. In the latter scene, Davies reprises Lean's use of a revolving barrel to imitate the lights of a passing train. Lean's film hangs over Davies's like a post-war pea-souper. The influence of Anthony 'Puffin' Asquith's Rattigan adaptations, The Browning Version and The Winslow Boy, is apparent too. At the LFF Press Conference for the film, Davies confessed that he dislikes the present. He loves the past though, a version of it anyhow, particularly the cinematic past represented in melodramas and musicals. The religious fervour of his boyhood was long ago superseded by evangelical love of movies (his conversion taking place after seeing his first film, Singing in the Rain, aged seven). The film is sandwiched between references to Derek Jarmans Blue and Orson Welles's Citizen Kane, but it is the string-laden musicals and 'women's pictures' he watched with his sisters in the '40s and '50s that determined his approach in The Deep Blue Sea.

When I interviewed Davies in 2008, just after his poetic documentary Of Time and the City was released, I asked him what his plans were. At that time, he was embroiled in a fruitless struggle to secure funding for an adaptation of Lewis Grassic Gibbon's Sunset Song, so we talked about that project. He also told me that he would love to make a musical. He is scheduled to work on a stage adaptation of Chekhov's 'Uncle Vanya', with which we wish him well, while hoping that he will return to film quickly. A first musical might be the way forward for him. If his enthusiasm for that form were given full rein, and if he were given the opportunity to create a world distinctly his own, he would surely produce something magical. In The Deep Blue Sea, his talents are constrained because confined within Rattigan's world, and even his sure touch with music occasionally deserts him.

In the opening scene of the film, in which Hester attempts suicide, images are overwhelmed by noise: for ten minutes the subtleties of the sequence are drowned out by Samuel Barber's 1939 Violin Concerto. Davies loves violin strings and clearly intended to tug at our heartstrings here, but the music merely irritates, or, to be precise, the loudness of it does. It pins our ears back. Jean Epstein, writing about the use of music in The Cinema Continues (1930), said: "One cannot look and listen at the same time . . . Music which attracts the attention . . . is simply disturbing." Of course, Epstein was writing in the twilight of the silent era, but one would hope that a filmmaker with Davies's normally attentive ear wouldn't fall so readily in line with mainstream cinema's tendency to deafen audiences. In this scene he bludgeons us into sign-posted submission. It's all so different to the subtle but powerful use of music in his earlier films, as we'll see shortly.

This is not the first time Davies has overplayed his hand. He did so in a similarly flamboyant way in the otherwise magnificent Of Time and the City. The lustrous images of that film are complemented by a soundtrack composed of judiciously selected radio recordings (BBC comedy Round the Horne, Grand National coverage, the football results), music (Handel, The Hollies, Mahler, The Spinners), elegiac poetry (Donne, Dickinson, above all Eliot's Four Quartets), quotations (Chekhov, Engels, Joyce) and Davies's voiceover narration – recorded in a single day. As the film's component parts collide and collude, before cohering into a greater whole, its juxtapositions provoke associations of feeling and thought that reinforce yet others, to powerful effect. But that packed soundtrack, particularly Davies's rhapsodic narration – by turns angry and arch, witty and whimsical – overwhelms everthing else. We often crave silence, that the images might speak.

In The Deep Blue Sea, Davies's admiration for Rattigan, musicals and melodramas drives a wedge between us and the film. Just occasionally, however, Davies returns to realities we can all recognise. One of the lodgers in the shabby house in which Hester and Freddie secretively conduct their affair, Mr Miller (Karl Johnson), stands in for Rattigan's sublimated signals about the lot of gay men in the Britain of his day. He plays a doctor struck off, we assume, for his homosexuality. Davies and Johnson depict Miller as a man hiding behind a mask of quiet dignity which cannot conceal his resentment and pain. When Sir William, with Hester's wellbeing at heart, enquires about Miller's medical qualifications, Davies allows Miller to snap angrily at the judge and declare that respect is something to be earned, not offered with the tug of a forelock.

It is as if the minor characters stand in for what Davies is straining to say, torn as he is between his capacity for heart-stopping realist vignettes and his love of broad-brush melodrama. The Davies of old, the Davies we know and love, surfaces during a fraught exchange in a dimly lit hallway. Shortly after a letter from Sir William theatrically reveals the affair, and Hester's true identity as Lady Collyer, Hester happens upon Mrs Elton as she gently comforts her invalid husband. Now Davies, through Mrs Elton, offers us the kind of home truth that could have come straight out of his earlier films: "You know what real love is? It's wiping someone's arse . . . and letting them keep their dignity, so you can both go on." If only Davies had not been so moved by admiration of Rattigan and his play that he rigorously policed his own voice, we might have been treated to more scenes and more dialogue with that kind of punchy force.

| Disappointment and betrayal |

|

History offers no conclusive proof as to whether it was the late Keith Butler or the late John Cordwell who shouted "Judas" at Bob Dylan during his now legendary 1966 gig at Manchester's Free Trade Hall, but both were intensely involved in the folk movement and would have been equally outraged when Dylan defied folk tradition to play the electric guitar, loudly, then more loudly still in angry reaction to that singular vocal intervention. In an erudite article in the London Review of Books, Adam Phillips uses that incident as his entry point into a counter-intuitive meditation on the positive, transformative aspects of betrayal. As Phillips notes, that famous accusation hastened Dylan's break with the past and strengthened his resolve to change, thus transforming pop culture. In similar ways, we are asked to believe, Jesus and the world were transformed for the better by Judas's betrayal. Phillips also reminds us that childhood development functions much like this, with each stage of natural growth perceived by the child as "a breach of trust, a loss of entitlement, a diminished specialness." We mature through a series of parental 'betrayals'; we learn and grow by 'betraying' our parents, in leaving home for instance.

What, you might ask, has this to do with Terence Davies and The Deep Blue Sea? Well, to begin with, the argument that the dialectics of betrayal play an essential part in human growth can be extended to film criticism, which, similarly, develops through a series of 'betrayals' – of earlier theories, influential movements and sanctified directors. The ideas elaborated by Phillips also provide a useful way of assessing the film's reception and a way to understand the widespread praise that greeted the film. He says: "Many of our uncompleted actions are uncompleted because they are forms of betrayal; failures of nerve that we have re-described to ourselves as commitment, loyalty, integrity or kindness. We are often loyal when we fear disillusionment." The film is so deeply flawed that we can only assume the more effusive reviews were shaped, or, more often, knocked out of shape by commitment to British Cinema, loyalty and kindness to Davies, and fear of disillusionment. That would be understandable. Davies has long been regarded by many, this reviewer included, as Britain's finest living director, so it was inevitable that much hope and goodwill was invested in The Deep Blue Sea after Davies's lengthy absence. A sense of guilt might have played its part too. Perhaps some critics asked themselves if they mightn't have done more to shame potential backers into digging deep for Davies. Anyway, the impatient excitement with which the film was anticipated, the general admiration and affection felt for Terence Davies, was such that a general, if generally guarded positive critical reception duly arrived, on cue, almost as a fait accompli.

My own feelings towards Davies and the film are similar to those Keith Butler and John Cordwell must have felt towards Dylan and his electric guitar: a mixture of admiration and disappointment. I, too, had hoped for great things from this great director, and was saddened to find merely an intimation and imitation of former glories. Had this been a film by anyone other than Terence Davies I might have been inclined to make light of its failings and praise it for its professional polish. As Adam Phillips says: "Once there is the possibility of betrayal a great deal has already happened: there can only be betrayal if there is a history, a real relationship of affinity. Betrayal is only possible when there is something to betray." Turning the film over in my mind since I first saw it at the London Film Festival, an uneasy, albeit mild sense of betrayal arose in response to Davies's departure from certain standards he himself had earlier set and from a certain way of representing our past that he previously embodied. Of course, betrayal cuts both ways, and reluctance to write about the film as I really saw it, warts and all, set in too, since to do so seemed to betray Davies. Phillips came to my rescue with an argument that overcame my sense of discomfort and disloyalty at taking the film to task.

Whether you think of The Deep Blue Sea as a failure or the best thing since sliced bread, those of us who have regarded Davies's films as the best of British cinema can speak of a deeper, more important level of betrayal than his or mine: that of our national film culture by those who refused this most gifted of directors the funding his talents deserved, and who thereby denied him the opportunity to work for so long. They must shoulder a share of the responsibility for the film's failure, since its failings flow partly from Davies's enforced absence from filmmaking. As the old adage suggests, 'practice makes perfect'; even someone as gifted as Terence Davies can learn from risks taken and mistakes made. Even skills as rare as his can be refreshed and refined by being consistently applied. They weren't and, consequently, he returned to filmmaking slightly rusty, reliant on familiar directorial tropes and techniques, and, as we shall see, prone to repetition.

Terence Davies is, of course, a victim of his own success. He is the magician surrounded by open-mouthed admirers, all calling out: "Ooh, do that again." Ever eager to please, he does. The Deep Blue Sea opens with a skillfully executed crane shot. The camera glides across the charred remains of bombed-out buildings, before climbing the peeling wall of a terraced house to close in on the film's heroine, who is framed in an upstairs window. As the gentle lilt of the BBC shipping forecast fades, to be replaced by the increasingly strident second movement of Barber's Violin Concerto, Davies then details Hester's attempted suicide in the dingy flat within. As the opening scene takes us deep, then deeper still into the past, it also returns us to Davies's directorial past. Those familiar with Distance Voices, Still Lives will have felt a frisson of recognition as they watched The Deep Blue Sea begin, for its opening sequence echoes the crane shot with which his earlier film began. On that occasion the camera frames a neat terraced house, it is bucketing down with rain, we watch a woman in an apron (the mother, played by Freda Dowie, foil to a psychotic father played by the late Peter Postlethwaite) as she stoops to collect three pints of milk from her front doorstep, we hear a familiar sound: "The shipping forecast for today and tonight: Iceland, Bailey, Faroes . . . Fair Island, Cromarty, Forties." The law of diminishing returns dictates that we are less affected by the repeat performance in The Deep Blue Sea; the trick is familiar already and the magician begins to look slightly shabby, a little disreputable now that his brilliant, deceptive arts have been revealed.

Davies's signature tracking shots are replicated in the film too. Interviewed by Kevin Jackson for The Independent in 1988, Davies said: "A track is incredibly powerful and intimate. It draws you into the film emotionally . . . because we read from left to right, a camera track left to right indicates a forward movement; a track in the opposite direction suggests a journey back in time." Let's compare two tracking shots. In Distant Voices, Still Lives Davies created the closest thing to a perfect film poem ever made in England. In one sublime scene, subtly stitched together by a stirring rendition of 'Love is a Many Splendored Thing', the camera moves from a rain-drenched posy of upturned umbrellas clustered like lily pads (a homage to Singing in the Rain), before gliding slowly up the glistening wet walls of a cinema. Then, after a cut so deftly handled that it doesn't break the movement's seamless rhythm, the camera moves over the heads of an audience, before finally zooming in from the shadows to reveal the faces of two sisters, Eileen (Angela Walsh) and Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne). They are sobbing into their hankies, presumably as they watch William Holden and Jennifer Johnson on the screen. Each time I watch that scene, I cry too – at its exquisite beauty. It moves us because it reflects on cinema's capacity to move, because tears move us to tears, but also because it is one of the most perfectly executed and elegant camera movements in film history.

A prominent flashback sequence in The Deep Blue Sea, filmed in the disused Tube station at Aldwych, replicates the scene from, or, rather, a cliché of the Blitz. The dull boom of a bomb burst silences those huddled together below ground. A curtain of dust and fine rubble falls from the tunnel roof onto the tracks. After a stunned silence, the defiant cockneys break into disgnified, if subdued communal song. As they sing 'Molly Malone', the camera tracks, from right to left, down the length of the platform, before settling on Hester and Sir William as the far end. This single-shot track, like the one in Distant Voices, Still Lives, is flawlessly executed, but it feels matter-of-fact. Actually, it amounts to a distortion of fact. All the stock characters of London wartime life are gathered here: policemen, ARP wardens, nurses, sailors, soldiers, workers. They are carefully arranged and suitably clothed. It is as if Davies had commissioned The Imperial War Museum to put on a show. Because we are not offered any grounding context for it, because the film has not introduced us to the people we see, it doesn't work. It should move us deeply, as deeply as Humphrey Jennings's London Can Take It! does and for similar reasons, but, like so much of the film, it feels staged; so mannered and stylized that we merely marvel at the skill of it all, without having anything to bite on emotionally.

| Communal singing as class solidarity |

|

Davies's attuned ear and keen eye have regularly combined to serve up magical meetings of music and image. Even that knack lets him down here, although, granted, it does produce the most ravishing scene in the film: the one in which Freddie and Hester are silhouetted against the backdrop of a pub's rich woodwork and glittering glasswork as they dance, as if in a swoon, to Jo Stafford's exquisite torchsong, 'You Belong to Me'. Elsewhere, unfortunately, the pub sing-alongs that achieved such impact in Distant Voices, Still Lives feel slightly stale. Again, as in that set piece at Aldwych Underground station, we look and listen to a Britain we recognise but can't enter. Because the ordinary citizens of London exist beyond the film's claustrophobic interior, we are offered no reason for empathy with the communal singers. With the grounding context of community entirely absent, these are just songs, and staid ones at that. Few will be moved to tears by 'How 'Ya Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm'. Many thousands, however, this writer included, have been moved to tears by the pub sing-alongs (to 'That Old Gang of Mine', 'Brown Skinned Girl' and 'If You Knew Suzie') in Davies's masterpiece. It isn't a matter of the quality of the songs primarily, but of connection to the singers. We are moved by the singing Scousers in Distant Voices, Still Lives – even when they sing 'What a Rotten Song' – because we have been introduced to them already. We feel we know them. We feel we are them.

The music in The Deep Blue Sea doesn't compare favourably, either, with its use in the centrepiece of Davies's Of Time and the City, his enraged meditation on the folly of destroying terraced streets, and a community spirit built up over generations, in order to re-house people vertically, in Brutalist tower blocks. Footage of houses being demolished flows into footage – largely lifted from fellow NFTS alumnus Nick Broomfield's early documentaries, Who Cares (1971) and Behind the Rent Strike (1979) – of newly built high-rise flats in Liverpool's Everton Valley, before, finally, in the aftermath of social dislocation, we observe the bewidlered faces of the re-housed. All this to the sound of Peggy Lee singing 'The Folk Who Live on the Hill'. The effect is bleak but, simultaneously, breathtakingly beautiful and deeply moving, because the social and historical context is there.

If our national past is to be portrayed accurately, the importance of music and movies in shaping a shared sense of community, what Benedict Anderson called "a deep horizontal comradeship," must be taken into account. Distant Voices, Still Lives did so like few others. It is full of perfectly pitched references to popular culture, showing how it provides both individual emotional sustenance and, to some degree, the binding glue of communal cohesion. Music is central to the success of the film, which represents a rare attempt to present a truth about working class life untainted by institutional forms of rhetoric. John Osborne, reflecting on Pen Tennyson's Ealing Classic, The Proud Valley, on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs, pointed to the use of communal singing as a metaphor for class solidarity. Music binds in much the same way in Distant Voices, Still Lives. Although solo singing is used to moving affect too, as when Doreen (Pauline Quirk) sings 'Dreamboat' and Dave (Michael Starke) sings 'Up the Lazy River'. As the Liverpudlian poet Paul Farley notes in his superb BFI Modern Classics monogram on the film: "The popular music that saturates (it) as much as any coral filter means viewers are not only offered an accurate period 'sound world' to inhabit, but they are also invited to bring their own memories to the table." The Deep Blue Sea is a sumptuous banquet for and about the select few, while Distant Voices, Still Lives was a feast of memory to which all of us were invited.

I compared Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Deep Blue Sea not just because the one reveals the flaws in the other, but also because they embody different approaches to the past. Harlan Kennedy's review of Davies's earlier film makes manifest the differences between the two films. Kennedy wrote: "For Davies, the past is not a foreign country in the sighing, elegiac sense . . . for Davies, if the past is a foreign country it's guerrilla territory; not a sedate outpost of our existential empire but a Vietnam of the mind. There, emotions are not languidly picked over with a calf-gloved hand; they come out of the shadows, raw and ungloved, and pick you over." The same cannot be said of The Deep Blue Sea. To put it bluntly: it is a heritage film just as surely as his earlier film was an anti-heritage film. I'll close, therefore, with a few thoughts framed by the ground-breaking theories laid out by my old Film Studies tutor, Andrew Higson, whose work on the slew of '80s films that he defined as 'bourgeois heritage' helped establish the term 'heritage' as the stuff of sound-bite journalese. Heritage theory remains all too relevant. David Cameron's philistine comments on cinema and his asinine decisions about film funding are underpinned by heritage ideology. Deep as we are in another recession, it is worth restating Higson's case, which casts considerable light on Davies and The Deep Blue Sea.

Writing about the Rattigan centenary celebrations in The Guardian,* David Hare decries what he called, "a national festival of reaction," in terms redolent of heritage theory. He dismisses the re-writing of thesbian history that has positioned Rattigan as a hard-done-by victim of cultural change, a martyr shamefully overlooked due to the belated opening up of the British stage to working-class voices in the '50s. Hare says: "Of course, you must expect it: in rightwing times, rightwing art flourishes. In the London theatre, the Donmar Warehouse has prospered by seeking out religious mystic playwrights of the last century like TS Eliot and Enid Bagnold . . . At the cinema, The King's Speech has swept all before it . . . And on television the nation has been sitting down to an Edwardian fiction, Downton Abbey, in which the upper classes are revealed, to the astonishment of the grateful viewer, to be quaintly caring about the welfare of the lower."

Hare continues: "Those of us who lived through the Thatcher years will remember how, for the first time, the powerful and successful were encouraged to develop an ugly vein of grievance. To the beaming approval of the Prime Minister, fabulously wealthy business folk took to telling us how little appreciated they were, and how intolerable it was to carry an equal burden of taxation and misunderstanding. With Cameron in charge this wheedling tone of self-righteous privilege is back in the public discourse. The attempt to turn Rattigan into a martyr is simply its cultural equivalent." If Davies repeats techniques honed during his own filmmaking history in The Deep Blue Sea, he does so as history repeats itself more obviously than usual in the wider world. Heritage, like Rattigan, never really went away; if it had done, it would now be back with a vengeance.

In Dissolving Views, an anthology he himself edited, Andrew Higson pointed out that heritage films represented an "effort to carve out a space for British, or English, films in a market dominated from the mid-1910s by the American film industry." Starting from the premise that the ruling class is as overrepresented in cinema as the working class is underrepresented, he argued that heritage films present, market and naturalise a nostalgic, reactionary and stylised version of Englishness. Ring any bells? Heritage, Higson argues, has its antecedents, notably in the output of Gainsborough Studios, but was, essentially, a by-product of Thatcherism. De-industrialisation and the aggressive wave of privatizations in the '80s were accompanied by a concomitant policy of cultural de-nationalisation (entailing the founding of Channel Four in 1982, the abolition of the Eady Levy in 1984, the Cable and Broadcasting Act of 1984, and the Broadcasting Acting of 1990); all of which prepared the ground in which heritage grew. Meanwhile, abroad, international recession accelerated Britain's decline as a global economic power, a process exacerbated by the intensification of globalization and the growth of multi-national corporations. As Higson says in Fires Were Started – British Cinema and Thatcherism, such changes "disturbed traditional notions of national identity," notions already threatened by 'the empire coming home' – in the form of multiculturalism, and the 'the chickens coming home to roost' – in the form of the social unrest ignited by growing inequality and record levels of unemployment.

Amidst the upheaval and uncertainty of the Thatcher years, and an increasing assertiveness within local nationalisms, a desire arose for the comforting 'certainties' of heritage and the re-assertion of a version of the national past that excluded both the working class, the gay and black communities, and provincial or 'other' Britain. In their essay 'Great Britain Ltd' (which introduces the anthology Enterprise and Heritage: Crosscurrents of National Culture), John Corner and Sylvia Harvey argued that, under the circumstances outlined above, Thatcherism cast around for ideological strategies to fuse the old and new, tradition and modernity; hence 'enterprise culture', to denote dynamism and change, and 'heritage culture', to stitch together a frayed and unravelling nationalism. To paraphrase Voltaire: "If heritage didn't exist, it would be necessary to invent it."

What Andrew Higson called "the heritage cycle of films" included Chariots of Fire (1984), A Passage to India (1984), Room with a View (1986), Howard's End (1992), Sense and Sensibility (1996), Pride and Prejudice (2005) and, most recently, The King's Speech (2010). It also includes works for television such as Brideshead Revisited (1981), Jewel in the Crown (1984), Pride and Prejudice (1995), and, most recently, Downton Abbey (2011). The list is long, and, especially in the year of the Dickens bi-centenary (with TV and film versions of Great Expectations, et cetera), will continue to grow. I would add The Deep Blue Sea to it. Like those films, it creates and re-creates an elitist, exclusive past. As Patrick Wright says in On Living in an Old Country, this is the past "purged of political tension" and, therefore, ready for appreciation as visual display by means of "an obsessive accumulation of comfortably archival detail."

The set piece sequence on Aldwych Underground station in The Deep Blue Sea is a case study of that tendency. So, too, is the earlier scene that affords us our first glimpse of Freddie and Hester together. Freddie poses in front of carefully arranged and polished golf trophies and clubs. He beams at Hester, his teeth gleaming like the trophies, as the sun shines on the green landscape beyond. It might be a photograph used in a 1952 advertisement for Brylcreem or Harris Tweed. In keeping with heritage cinema, the period detailing is faultless throughout the film: every button on every coat, every advertising prop, alley, car, costume, hairstyle, hat, flat, house, pub, pub song, and street says: "Welcome to the 1950s."

Heritage cinema replaces the social and cultural present with mythical versions of the past; the past, as Higson says in Re-presenting the National Past, "displayed as visually spectacular pastiche, inviting a nostalgic gaze." In heritage we detect the troubled breathing of a class and a society in retreat from an uncomfortable present and taking refuge in a comforting past, much as Davies does. That may seem odd given that the social circumstances of gay working class men has markedly improved since he was a boy. Davies's nostalgic view of the past, though, is shaped not by social realities but, rather, by a sense that the present is vulgar. For him, our films aren't as spectacular or sparkly, our clothing isn't as well made and elegant, our popular song isn't as witty or literate and we can't sing anymore. For Davies, time stopped somewhere in late '50s or early '60s. The warning signs were there in his last film. He sums his own attitude up, in his own words, in Of Time and the City, in the testy moment when he snaps, "yeah, yeah, yeah," over an image of The Beatles, thereby cynically dismissing the tastes of whole generations. The heartfelt rancour and aggression of that sneer reveals the depths of Davies's curmudgeonly distaste for the modern and modish.

As Of Time and the City begins we find ourselves beneath 'The Dockers Umbrella', as Liverpool's Overhead Railway was called. The world's first electrified elevated railway, it was demolished in 1958, so, as Davies intones first the closing lines of A.E. Houseman's 'Blue Remembered Hills' ("The happy highways where I went/And cannot come again"), then of Shelley's 'Ozymandias' ("Round the decay/Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away") the scene is set for all that follows, in his own and his native city's history. Davies, who left Liverpool in 1973, literally cannot return, for the streets of his childhood were demolished during 'slum clearances' and industrial Liverpool was swept aside by Thatcherism. So, Davies flees a troubling present (a city he no longer recognizes) into a comforting past (Liverpool at a safe nostalgic distance). His is now an outsider's perspective on working class Liverpool's past. His abundant talents have enriched our lives. They have also carried him a long way from his roots. His audiences and his interests now lie beyond Liverpool. Davies is the embodiment of embourgeoisement.

To return to heritage theory, if The Deep Blue Sea is heritage writ large, Davies's earlier films represented a coherent challenge, intentional or otherwise, to the distorting narratives of heritage films. They proposed different versions of Englishness and the past, whilst yet displaying many of the hallmarks of heritage cinema. They sat within a group of films that Phil Powrie labelled 'alternative heritage'. This cycle of films presented the past in costumed detail like heritage proper, however, whereas heritage films leapfrogged recent history, the 'alternative' current tended to focus on the war and post-war period, insisting, in one way or another, that the English past was a cupboard full of skeletons; implicitly insisting, too, that all was not well in Albion in 'the present'. 'Alternative heritage' consists of largely autobiographical films (often referring to the war, often directed by gay men) such as the Terence Davies and Bill Douglas trilogies, John Boorman's Hope and Glory [1984], Derek Jarman's The Last Of England [1988] and, of course, Davies's Distant Voices, Still Lives.

Davies and Douglas, Boorman and Jarman, were all products of the egalitarian Butler Act of 1944, part of a generation offered opportunities for personal progress though education. They gratefully seized that opportunity and an artistic sensibility shaped by it as surely as their memories of the war. The similarities between Davies and Douglas are particularly striking: both found in film an escape from violent fathers and poverty, both grew up gay and were surrounded by intolerance, both were nurtured by the NFTS, both made cathartic trilogies about their childhoods, both subsequently stood by their cinephile principles as painstaking perfectionists, only to fall foul of funding bodies demanding quick results and returns, both were marginalised by an infantalised culture scared off by their adult messages, both made films that remain among the crowning glories of British cinema, rising to their full heights to stand at the pinnacle of world cinema.

Of course, these directors were not alone in challenging the complacent assumptions of heritage cinema. Another group of films, generally set in the present or recent past, also portrayed the darker truths of a damaged, post-imperial and heterogeneous Britain. These films, unlike heritage, were more interested in people than buildings and costumes. They were also more interested in working class life in the urban 'now', than, for instance, in rural middle-class life in days gone by. It has long been a commonplace that British cinema can be divided down the middle, with heritage cinema on the one side and Social Realism on the other. That oppositional tendency, often discussed in relation to the work of Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, can trace its ancestry back to the Griersonian documentary movement, Free Cinema and the British New Wave. It includes films such as My Beautiful Launderette (1985), Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1986), Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1988), Brassed Off (1996), The Fully Monty (1997), Trainspotting (1996), Ratcatcher (1999), This is England (2006), Neds (2011), and Sket (2011).

Whether or not we agree with the late John Orr's bold claim that, "Film is at its most effective when it challenges national identity, when, far from confirming it, it points out our contradictions or frailties of perception, when it unveils discord or division," we can see that the audio-visual battle lines are constantly being drawn and re-drawn. On one side stand the likes of Derek Jarman, Mike Leigh, Peter Mullan, Lynne Ramsey, and Terence Davies. On the other side stand heritage directors such as James Ivory, Tom Hooper, Hugh Hudson, David Lean, and, now, Terence Davies. It is as if a cultural civil war were constantly being waged, with the past as booty. The distance between Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Deep Blue Sea – like that separating A Room at the Top and A Room With a View – is the distance between competing versions of the past and of national identity. With The Deep Blue Sea, Terence Davies has defected to the enemy camp. The film should feel epic, but it looks like decoration.

* http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/may/31/terence-rattigan-theatre-reaction-martyr

|