|

Two directors we will definitely be hearing more of are Chile's Dominga Sotomayor and Scotland's Scott Graham: having delivered sublime debuts of great maturity and depth in Thursday Till Sunday and Shell respectively, both have second features in production. As last year's foreshortened 12-day Festival began, I expressed unease about cinema's continuing reliance on literary sources of inspiration, so it was particularly pleasing to hear that Sotomayor and Graham are at work again already. They are writer-directors capable of crafting daring, distinctive films from their own original scripts and, what's more, of doing so with an admirable economy of style, in response to the inner logic of the stories they tell. Sotomayor and Graham share a restrained, controlled approach to filmmaking that enables situation and character to develop organically and grow naturally, rather than arriving as fait accomplis, enshrined in plots, screenplays, or storyboards that operate as binding contracts. Sotomayor and Graham also share an acute awareness of landscape and the virtues of the long take, an interest in the small moments that mark and shape their observant central characters (both young women), and a view of adolescence as complex and conflicted – all of which pays dividends in these intimate, intense, and intelligent films.

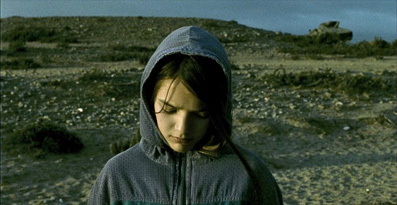

Thursday Till Sunday (De jueves a domingo) follows a petit-bourgeois family foursome's four-day journey from verdant Santiago to the arid North of Chile. Sotomayor's award-winning film opens in the dim light of dawn, with the sleeping figure of its adolescent protagonist, Lucia (13-year old debutant Santi Ahumada), in the foreground. We watch as Lucia is awoken, we watch through her bedroom window as the family car is packed for a nominal camping holiday, and, thereafter, we watch her parents' relationship disintegrate through Lucia's eyes. As the family prepares to depart, Lucia's mother, Ana (Paola Giannini), asks her husband, Fernando (Francisco Pérez-Bannen), if he really wants her to go. It is our first inkling that all is not well between the couple. Early in the journey, Fernando pulls up at the roadside. Lucia and her 7-year brother, Manuel (Emiliano Freifeld), leave food for a man whose wife was killed in a crash and who has lived on the hillside above the road ever since. It is an unsettling episode that immediately insinuates unease.

Later, we learn that Lucia's father has a hidden agenda, to visit a parcel of land inherited from his father, and we have our first hint of his duplicitous nature. Despite his superficially anarchic, democratic sensibilities (he steals fruit, he prefers the battered crate he drives to flashier cars, he lets his kids ride on its roof), Fernando is revealed as an old-fashioned patriarch who prefers his 'son and heir' over his brighter daughter. At one point, Lucia asks to drive and he initially refuses her request. Towards the end of the film, he shares his proprietorial pride in his inherited land with Manuel not Lucia. Such moments are typical of Sotomayor's psychological insight, sure grasp of detail, and tendency to reveal her story incrementally. Her style is less 'show, not tell', more 'suggest, not tell'.

Warnings about plot spoilers are, therefore, unnecessary with this beautiful film, for it is not primarily through a structured plot that Sotomayor weaves her magic, but, rather, through her use of lenses and looks, by deploying image elegantly, and by releasing information sparingly. As the family's northward journey progresses, the tension between Lucia's parents mounts, the couple's sullen silences multiply, and the landscape increasingly reflects the aridity and decay in their relationship. Working closely with her cinematographer Bárbara Álvarez (best known for her work with Lucrecia Martel on La mujer sin cabeza/The Headless Woman), Sotomayor places us in the car with the family, drawing us into claustrophobic intimacy with the characters, and revealing how Lucia reaches an understanding of what is happening to her parents. Sotomayor does this by alternating fixed-position shots within the car, where we are see things most often from Lucia's point of view, with wide-angle shots in open air, where the family and those they meet upon the way are placed against the backdrop of an alienating larger landscape. The rhythm of the journey is reflected in that of the shots, the disintegration of the relationship is reflected in the film's increasingly muted palate. The camera is placed at the service of characterization. We come to identify with Lucia, because, like her, we glimpse her parents from behind: from the backseat, over their shoulders; seeing the sides of their faces, their glances and their avoidance of glances, while eavesdropping their stilted conversations. As slowly as Lucia does, we gradually grasp that we are watching the implosion of a marriage and are riveted throughout until the film reaches its tense, if inevitable climax in an aptly lifeless lunar landscape.

Thursday Till Sunday is, of course, a Latin American road-movie, and the first film that sprang to mind as a useful comparison is Pablo Giorgelli's Las Acacias – a hit at the 2011 London Film Festival where it was awarded a Sutherland Prize, and a film I reviewed here. When I mention Giorgelli's film, Sotomayor told me: "I haven't seen it yet, but that comparison has been made. A couple of French critics called my film 'the anti-Las Acacias'." She cites among her cinematic influences Antonioni, Roy Andersson, and Cassavetes, despite his fascination with conversation. She says: "Cassavetes without words. The images are more important. What interests me is how to create a complexity that can't be explained in words, to explore how to make emotion visible. I'm always very connected with the camera. What I like about film is logical and complex mise-en-scène. I like some adaptations but I don't think they should be necessary. I'm more interested in why, sometimes, it's not necessary for the camera to move. We really only used five camera positions for the film."

Sotomayor's deft deployment of the camera and of the Chilean landscape as a shadowy presence, and her unsparing if understated depiction of the unspoken dynamics of a family, are complemented by her sensitive handling of a young woman's experience of growing up. The camera ensures that it is Lucia we empathise with. In coaxing a performance of intelligence and subtly from Santi Ahumada, Sotomayor was ably abetted by her own mother, a well-known Chilean actress who helped prepare the child actors for their parts and who cast the boys in the film. Sotomayor herself 'found' Santi Ahumada, while she playing in a swimming pool with her own sister. The Chilean director clearly identifies, as we do, with Lucia, and the mother-daughter relationship is as important to the film's success as the husband-wife one. Although Sotomayor refuses easy categorization as a feminist director, Thursday Till Sunday derives much of its power from her handling of the women and children at its heart.

As Sotomayor and I compared notes on our favourite directors, our conversation turned to two titans of Chilean Cinema, Pablo Larraín and Patricio Guzmán, and to Chile's recent history – aspects of which are brilliantly delineated in Larraín's latest film, No, one of the surefire successes of the Festival, and in Guzmán's latest, Nostaglia for the Light. Sotomayor said: "I grew up in a non-political generation. Now things are happening again, but politics wasn't part of my childhood. It just wasn't discussed at school. But there's something political about my film - its discourse, its way of discussing the world. Everything's very fragmented so the frame can't hold it all. Take the kids: everything's falling apart and the adults are trying to control them. I love the way kids can completely change what the adult world wants from them. I like their craziness and passion and honesty." It is partly Sotomayor's appreciation of that unfettered honesty, and its reflection in the film, that makes Thursday Till Sunday so refreshingly fresh. More than anything, she said, her own childhood is her foremost influence. She lived with her script for several years before it all poured out, partly from own experience: "The film came naturally from observation. I wanted to make the audience slightly uncomfortable and the journey to be without 'big moments' - to be about transitions and the connections. Some of it came from my childhood. I was obsessed with driving. I learned when I was about fourteen. It's part of Lucia's need to be independent and it was part of mine. Lucia is what her mother was 25-years earlier. She is the future." We can be thankful that Sotomayor, and Scott Graham, will be part of cinema's future.

|