|

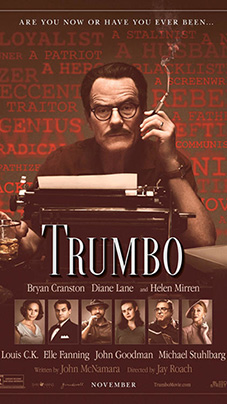

Prominent among the many American myths that need dismantling for good, and for the good of all is that of Hollywood as a hotbed of radicalism with Reds beneath it. It was always a fiction, a comforting bedtime story America told itself to ward off nightmares born of nagging doubt and gnawing fear. The corollary fairy tale depicting Hollywood as a bastion of liberalism, equally, demands alert scrutiny. The sleepiest of glances reveals an institution riddled with conservatives, riven by misogyny and racism, but still occasionally willing to look itself in the face, albeit in a distorting mirror of its own design. Trumbo, Jay Roach's breezy biopic about the brilliant blacklisted novelist and scriptwriter Dalton Trumbo, goes some way towards restoring one's fondness for Hollywood by inserting a measure of honesty into its account of itself. Though schmaltzy; as one might expect given that this is another story of, by, and for Hollywood; the film does come clean about Hollywood's craven response to censorship and political persecution, the anti-democratic activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and the wider paranoia of McCarthyism.

Jay Roach's sunny approach to such dark material jars at times but the fun he has with the famously witty writer's life, and with a series of set piece scenes in which we are invited to chuckle in recognition of the famous faces and films we encounter, is infectious. A stellar cast makes most of John McNamara's lively, if over obvious screenplay (largely adapted from Bruce Alexander Cook's 1977 biography Dalton Trumbo). Prodigiously talented lead actor Bryan Cranston plays Trumbo with convincing verve and evident relish. His versatility is seldom stretched in Trumbo, but he immediately refocused to refine his impersonation of President Lyndon B. Johnson for Roach's imminent HBO TV series All the Way. While facing down his enemies, Dalton Trumbo drew heavily on his tight-knit, hard-pressed family's support. Vital, then, that Diane Lane as Trumbo's wife, Cleo; Becca Nicole Preston and Elle Fanning as his grown-up daughters, Mitzi and Niki; and Mattie Lytak as his teenage son, Christopher, cohere on screen. They do so convincingly.

As an added bonus, Trumbo's surviving children, Niki and Mitzi, roughed up what would otherwise have been an unbearably saccharine script, not only by insisting their late father's hot temper and embattled over-reliance on stimulants be represented but also by persuading the producers to jettison a projected mushy ending entailing a cutesy rapprochement with John Wayne (David James Elliott). Louis C.K. as Arlen Hird, Trumbo's comrade and conscience; John Goodman as Frank King, a huckster producer with a heart of gold; and Helen Mirren as Hedda 'Hats' Hopper, the venomous gossip-columnist and rabid anti-Semite, deliver notably impressive additional support. Jim Denault's cinematography is crisp and the film benefits from Roach's judicious decision to build upon the firm foundations of archive footage. By switching switch back and forth between grainy black & white and brilliant Technicolor, Roach leaves us feeling we are skipping to and fro between past and present, thereby emphasising the film's contemporary relevance.

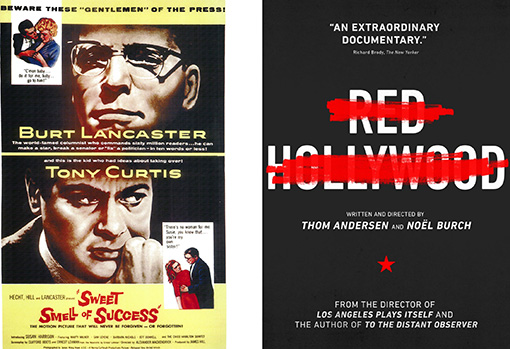

For all its virtues, Trumbo possesses neither the snarl of Emile de Antonio's more purposeful documentary Point of Order (1964) nor the snap of Thom Anderssen and Noël Burch's more intelligent essay-film Red Hollywood (1996) – films focused, respectively, on the 1954 Senate Army-McCarthy hearings and the actual social content of the films made by those blacklisted. In both tone and content, Trumbo is closer to Walter Bernstein's more light-hearted blacklist drama The Front (1976), in which Woody Allen acts as proxy Howard Price and blacklisted actor Zero Mostel plays blacklisted actor Hecky Brown. Although those films provided invaluable insights into the blacklist, and although imperishable classics such as Cy Endfield's The Sound of Fury (1950) and Alexander McKendrick's Sweet Smell of Success (1956) had earlier offered allegorical challenges to the blacklist, the refreshing, potentially cathartic candour of Roach's film nonetheless stands as an essential cross-examination of and self-examination by Hollywood itself.

While targeting actors, directors, producers and screenwriters' as symbols of an illusory 'Red Menace', HUAC established a climate of fear in Hollywood that stifled creative independence, did untold damage to freedom of speech and thought, and generated a climate of fear that has since abated but lives on in a corrosive culture of self-censorship. When, in September 1947, HUAC subpoenaed 24 'friendly'' and 19 'unfriendly' witnesses selected from a list of 'subversives' drawn up by the Hollywood Reporter, it set in motion a politically repressive juggernaut that crashed through American liberty and dealt Hollywood a blow from which it has yet to fully recover.

To paraphrase philosopher Noël Carol's wry comment on Direct Cinema, "Hollywood opened up a can of worms and was then eaten by them."

Trumbo does sterling work by detailing the part its subject played in many of Hollywood's finer moments as well as in its most shameful episode. There were good reasons Dalton Trumbo was Hollywood's, and therefore the world's highest paid screenwriter before the storm of McCarthyism broke. He won Oscars for Roman Holiday (1953) and The Brave One (1956) while working under pseudonyms during the period of the blacklist, successfully challenging that toxic outgrowth of McCarthyism with Exodus (1960) and Spartacus (1960), and continued to attack its legacy in films such as The Sandpiper (1965) and Papillon (1973). Whether Roach and his team designed Trumbo with the Oscars in mind only they can say. The film's easy-on-the-eye production values and light-hearted vibe suggest they did. If so, they deserve considerable credit for a brave shake of the dice: this may be a politics-lite, conventional crowd-pleasing tearjerker, but it faces down McCarthyism's lingering legacy by refusing to shy away from the awkward fact of Trumbo's controversial temporary commitment to communism.

The risk Roach takes is akin to that taken by Edward Dymtryk and Dalton Trumbo in 1943 when they named their wartime drama about a group of women pitching in together as housemates and "running the joint like a democracy" . . . Tender Comrade (1943). The film was a huge box office success but ultimately had disastrous consequences not only for Dymtryk and Trumbo but for Ginger Rogers, who starred in the film and whose mother tied herself in knots while testifying before HUAC. Lela Rogers told the committee that her daughter had been "forced" to utter the subversive line "Share and share alike, that's democracy," in Tender Comrade. Mrs Rogers also testified against Clifford Odets, claiming he had placed communist propaganda in his script for None but the Lonely Heart (1944). Mrs Rogers said: "I will tell you of one line. The mother in the story runs a second-hand store. The son says to her, 'You are not going to' . . . in essence . . . I am not quoting this exactly because I can't remember it exactly . . . He said to her: 'You're not going to get me to work here and squeeze pennies from people poorer than we are.' Many people are poorer and many people are richer. As I say, you find yourself in an awful hole the moment you start to remove one of the scenes from its context." And when you try to finger people for free expression of honest ideas.

Odets, of course, like screen tough guy Edward G. Robinson, was among those who dived for cover when the poisoned arrows of political battle began to fly. Both men amassed extensive collections of artworks when being extravagantly rewarded for their extravagant talents. In Trumbo, Robinson (gamely played by Michael Stulhberg) sells one of his paintings to help the cause of the Hollywood Ten. Odets, too, was generous with his collection. He frequently lent his works of the European masters to friends, merely asking they return them when they'd finished them. The morning after Odets, the darling of the left, buckled and named names, he returned home to find his hallway full of returned paintings. He professed to being baffled, I profess to thinking that claim bullshit. From the start of HUAC's activies, it was apparent to all – left, right and liberal centre – that that famously delusional committee was conducting a modern inquisition. It is one of the myriad ironies of that tragic political drama, that a committee established in 1938 with the aim of rooting out Nazi sympathisers would establish a neo-Stalinist show trial.

Even before the 'unfriendly' 19 had splintered; first into 11, and then, after Bertolt Brecht's flight to Europe, into the refusenik Hollywood Ten; certainly long before the blacklist banished many from their profession and destroyed countless lives; two signals had been transmitted, both received loud and clear, that would reverberate down decades: the ancient warning, "Confess, submit, or we'll break you," and its modern manifestation, "You'll never work in this town again." Although, he refused to bend, Dalton Trumbo argued that both sides of the friendly/unfriendly fence were equally victims of the blacklist. Among the many victims we might name were Louis Adamic, Bartelby Crum, Mady Christian, Madelyn Dmytryk, John Garfield, Francis Otto Mathiessen, E. Herbert Norman, William K. Sharwood and Francis Young – all driven either to early graves or suicide by innuendo and intimidation.

In an often-quoted comment culled from his Screen Writers' Guild Laurel Award acceptance speech of 1970, Trumbo said: "The blacklist was a time of evil, and no one on either side who survived it came through untouched by evil . . . it will do no good to search for villains or heroes or saints or devils because there were none . . . in the final tally we were all victims because almost without exception each of us felt compelled to say things he did not want to say, to do things that he did not want to do, to deliver and receive wounds he truly did not want to exchange."

Jay Roach appears to take a different view. He clearly regards Dalton Trumbo as exceptional – the brave one, standard-bearer of rugged American individualism and shining embodiment of principled opposition to unscrupulous intimidation. With considerable justification, Trumbo presents Hedda Hopper, Edward G. Robinson, Louis B. Mayer (Richard Portnow), and J. Parnell Thomas (James DuMont) as villains of the piece; Kirk Douglas (Dean O'Gorman), Otto Preminger (Christian Berkel), John F. Kennedy (Rick Kelly) and Trumbo himself as its heroes. The above-mentioned speech, delivered while Trumbo was directing Johnny Got His Gun (1971), an adaptation of his own anti-war novel of 1938, contains commonplace truths about the human condition ('Which of us can say how we'd respond to dark, testing times of which we have no knowledge?'). It also testifies to Dalton Trumbo's elegant generosity in offering an olive branch to those he had every right to despise.

In Peter Askin's deft documentary Trumbo (2007), based on the play Red, White, and Blacklisted by his son Christopher, he delivered a contrasting comment perhaps more representative of his general feelings. Reflecting on the jokes he often made about Robert Rich, the 'front' who received Trumbo's Oscar for The Brave One, he said: "I can make no more jokes about Robert Rich. They turn sour on my tongue. I can invent no more jokes witticisms about the Oscar he did not collect because that worthless golden statuette is covered with the blood of my friends. I cannot laugh about it any longer because my belly is filled with the poison of the blacklist, my head is filled with its grief, my ears roar with its rage and its injustices, and my heart, for the first time is filled with something very close to hate."

When Trumbo said that he may have been thinking of the likes of Whittaker Chambers, the lying turncoat informer who first named names for HUAC, of Hester McCullough, the McCarthyite zealot who named Paul Draper and Larry Adler and ruined their careers, and of now forgotten ordinary citizens whose only crime was to take a dim view of injustice, racism and political repression. Nelson Algren was certainly thinking of them when he wrote in Non-conformity, his thunderous response to McCarthyism: "When we can make a half-hero out of a subaqueous growth like Whittaker Chambers, and a half-heroine out of a broomstick crackpot like Hester McCullough, and then place a government employee under charges because unidentified informants alleged 'his convictions on the questions of civil liberties extended slightly beyond that of the average individual', it is a time to call a halt."

Whether Hollywood responds to Roach's gamble with a gamble of its own by garlanding Trumbo with Oscars remains to be seen. It seems unlikely it would decline this rare, homegrown opportunity to wipe the slate, reach for redemption, and take a first faltering step toward truth and reconciliation. It is impossible to second-guess the Academy but the look and feel of the film will not have done its chances any harm. If Hollywood doesn't award Trumbo an Oscar or two, it will have committed a crime against its own better self if not a crime against film culture. And as blacklisted writer Abraham Polonsky says at the close of Anderssen and Burch's Red Hollywood: "All films about crime are about capitalism, because capitalism is about crime. I mean 'quote unquote,' morally speaking. At least that's what I used to think. Now I'm convinced."

|