"If an actor is going to let the role come to them,

they can't resent the fact that I'm willing to wait

as long as that takes. You know, the first day of

production in San Francisco we shot 56 takes

of Mark and Jake – and it's the 56th take

that's in the movie." |

David Fincher, perfectionist, and Kubrick-esque, multi-take director |

I know several industry professionals who scoff at any director

that needs more than ten to fifteen takes with a well rehearsed

cast and a good crew. Yes, one can readily appreciate Steven

Spielberg's need for over seventy takes of Bruce the shark

smashing through the window of a half submerged Orca while

a very wet and exhausted Roy Scheider rams an oxygen tank

into its mouth... seventy times. Bruce was hardly Anthony

Hopkins when it came to stagecraft. There are no animatronic

sharks in Fincher's meticulously detailed Zodiac and like its star Jake Darko (I can't even read or pronounce

Gyllenhaal) I am at a loss to discover what tiny subtleties

in performance are different from one take to the next.

Is there a mystical dimension that nestles in a director's

imagination, one where his/her movie resides and the actors

have to match this vision almost, one might say, absolutely?

Then again, you have to admire the balls. Multi-taking directors

like Fincher and Kubrick could be winding us all up... not

if their films are evidence against, they're not. These

are film-makers of rare talent and are deserving of the

time and effort afforded them. Let them shoot take... after

take, after take, after take...

You

know those movies in your life? The ones you can revisit

time and time again and still retain an echo of the experience

you had when they first knocked you out? Sometimes repeated

viewings actually encourage fresh ideas to the forefront

of your mind. That certainly happens if the feature has

been written with care and directed with real passion. Curiously,

my favoured twenty or so are a mixed bag ranging from out

and out classics to dumb actioners all the way around to

rom-coms. For fear of violent ejection from this site's

contributors' list, I will not name any save one of these

films (my street credibility will become avenue angst if

you know what's number eight on my list). I will proudly

say that, publicly, the chosen one is Alan J. Pakula's All

The President's Men. There is nothing in that movie

(nothing) that qualifies it as a moving as in 'in motion'

picture. The spine and various ribs of the piece are conversations,

simple conversations between people, not an explosion in

sight. There is no 'action' per se. It's two guys slogging

forward because they have grasped a small trace of fibre

that when pulled at the right time will unravel the entire

US government. How Pakula managed to make a taut as taut-can-be

thriller is down to riveting historical fact, sympathetic,

unfussy direction, clever structural plotting and earnest

performances. Let's not forget the dynamic slow burn of

the screenplay, initially written and subsequently disowned

by scriptwriter William Goldman after his producer (Redford)

went behind his back and hired the real Woodward and Bernstein

to draft a – in places – fictitious script. I don't know

why this movie is so exciting to me but I'm not its only

rabid fan.

David

Fincher should be well known to anyone reading anything

on a movie site with the word 'outsider' in the URL. It's

true that we've yet to review one of his movies here (if

he insists on taking so much time between projects... Zodiac is our first) but I have to say that (1) I was utterly floored

by Fight Club (the only 'Hollywood' movie

in the last decade to truly blow my socks off), (2) I reviewed Alien 3 positively (just for my own amusement

but I really did like it), (3) I loved The Game despite the ending's slight implausibilities and (4) still

champion Se7en despite being regarded by

my nearest and dearest as a sick whacko because I have seen

the movie many, many times. (5) I saw Panic Room as more of a technical exercise (it was OK but not a genuine

Fincher movie in my eyes, more like marking time and having

some fun with animating coffee pot pixels). Fincher is one

of 'those' directors, a person who takes his job very seriously

and produces meticulous work whether it's portraying a man's

life unravelling or in this case, several men's lives un-spooling

like dropped film reels on the hunt for a serial killer.

Few

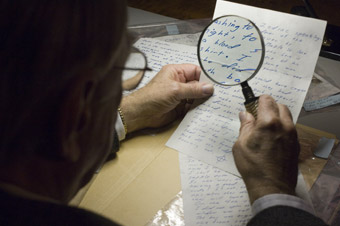

signature Fincher moments are present and correct. There

are graphics (of the serial killer's coded letters) splayed

out on police station's walls as the actors move through

them like the Ikea nesting instinct scene in Fight

Club. The digital interludes and scene settings

are so indistinguishable from reality that it's folly for

me to even suggest that they must have been shot in the

past on a camera from the future (the all-digital Viper,

a camera sans film, sans tape). The digital effects are

flawless and there are over 200 shots digitally enhanced

in the movie. Try as you might, you will not find one photographically

unreal pixel in the lot. What is starkly noticeable is Fincher's

visual style that seems to have not so much settled down

as taken out a mortgage – pray the pipe and slippers are

not the next step. He was once quoted as saying that there

were probably only two ways to shoot a scene... and "...one

of them was wrong." Fincher seems to have grown up

in the blink of a Viper's eye. He's now visually quoting

the major directors, (the Fords and Hitchcocks) anti-flaunting

and teasing out his own 'invisible technique'. To help secure

the facts of the real police cases he's dramatising, Fincher

felt it necessary not to embroider the action with directorial

flourishes. The mundanity of the staging gives credence

to the facts of the tale. Which is fine! Except when it

really isn't...

Yes, the style may respect the truth he's telling but in

so doing, Zodiac becomes little more than

a very standard police procedural (oh, it hurts me saying

this), one that stands or falls on the interest you have

in the real case and the believability of the actors. Fincher

is simply not at home despite some very obvious stylistic

tics – I smiled at the two very 70s logos at the start of

the movie, all scratches in place. Despite his small, wry,

casual remark on the Fight Club DVD ("if

we can only find a way of doing without the actors..."),

Fincher is extremely adept at getting great performances

from his overworked, overtaken thespians. The performances

in Zodiac are very convincing and the case

(a decade plus hunt for a serial killer who terrorised San

Francisco in the 70s) does have its moments.

If

his directorial skill and overwhelming stylistics do peek

out with a "Boo!", it's in the violence. The casual

and mundane bloodletting in Zodiac (three

serial killer killing moments on screen) is as straightforward

and horrific as you can imagine. I was primed for their

in-your-face nature but each of the kills has that same

nail biting intensity that so saturated the first five minutes

of Cronenberg's History of Violence. The

double stabbing is terrifying because of the extraordinarily

effective reactions, not the viewing of the blade penetrations

themselves. It was the first time in a cinema, I completely

imagined what it must be like being repeatedly stabbed.

Utterly horrific. Utterly terrifying.

The

case sparks the interest of San Francisco Chronicle reporter,

Paul Avery, played with an amiable, spaced out wiriness

by the master of amiable, space out wiriness, Robert Downey

Jnr. Downey is fascinated by a colleague's grasp and enthusiasm

for puzzles, the staff cartoonist played by Gyllenhaal.

The two men are drawn to open up to the Zodiac killer and

over many years allow their lives to be poisoned by his

morbidity and fear-mongering and talent for staying at large.

Clues come and go and the actual police procedural is conducted

by the detective whom Steve McQueen cited as a model for

his character Frank Bullit in, er, Bullit.

Mark Ruffalo plays Detective Toschi with a rogue determination

that makes him the most human copper this side of Sergeant

Dixon. If you don't know who that is then it's OK. Some

history can stay in the past. There is a sense in all of

Ruffalo's scenes that what you are watching is the real

deal. This is police work in all of its frustration, difficulty

and minutiae – all of which are appreciated within the movie

– and none of the Martin Riggs mega-stunts. It's about time

a policeman was a human being on screen.

Ruffalo's partner is sensitively played by Anthony Edwards

(so good not to see him embarrass himself as he did as Thunderbirds'

stutterer Brains). The lesser driven of the pair of detectives,

he is worn down by the chase/case and as the years drag

on, he is yanked back from the brink allowing his family

to take precedence over the relentless search for the killer.

The reporter and detective that stay magnetically attached

to the Zodiac nursing a great obsession to reveal this man

and lock him up are further galvanised by Gyllenhaal's cartoonist

whose life falls apart while he pores over case files and

newspaper cuttings pulling the kids in as researchers. The

movie is based on the cartoonist's two published books on

the Zodiac and to be fair to the material (a wealth would

be a relevant adjective), a two and a half hour movie was

never going to do the cases justice. But Fincher's narrative

is still sure footed as the details are scattered before

us like widely strewn jigsaw pieces. The director's command

of his story is absolute (structurally the film doesn't

drag or demand the viewer's IQ to be measured in hat sizes).

You have to be on the ball. But there's still that awful

word I used earlier; 'standard' and it's haunting this review.

I

used to resent getting school reports with the word 'satisfactory'

on them. It felt demeaning, worthless. I was of the school

that you either noticed me or hated me. I wanted to be thrown

out of my maths class or revered as a Hawking (such naiveté).

Disinterest was not an option. And so I find myself at the

feet of a director whose latest film drew admiration but

not effervescent praise. Zodiac does what

it does with intricate care and startling moments of 'wow!'.

It's a work of intelligence and passion with astounding

attention to detail.

But

for me, Zodiac's story (movie-wise) never

truly warrants the lavish attention and care spent on it.

I hang my head but that's my take (my first take) on David

Fincher's contemplative procedural. I'm curious about what's

next...

|