| |

“Heard about the guy who fell off a skyscraper? On the way down past each floor he kept saying to reassure himself: ‘So far, so good. So far, so good.’ How you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land.” |

| |

Opening line from La Haine, spoken by Hubert |

| |

Understand we're fighting a war we can't win

They hate us, we hate them

We can't win, no way

No fuckin' way Motherfuckers gonna pay

Motherfuckers gonna pay |

| |

Police Story – Black Flag |

When anyone takes the considerable time and effort required to write and direct a film they are passionate about making, they must hope it will make an impression, that it will click with the critics, find an appreciative audience, and even be an at least a moderate commercial success. Rarely, however, does a film have such an impact that the leader of the country in which it was made and set arranges a special screening for himself and his colleagues to get a better understanding of the social problems they are facing.* Such was the case for the 1995 film La Haine – which translates provocatively as ‘Hate’ – the second feature from then 27-year-old French actor turned writer-director, Mathieu Kassovitz.

It's the morning after a night of rioting on the Muguet housing estate just outside of Paris, disorder that was triggered by the violent beating of local French-Arabic teen Abdel Ichaha (Abdel Ahmed Ghili) while in police custody, an assault that has left him in hospital in critical condition. With the police presence on the estate still strong, young resident Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) hooks up with his friends Vinz (Vincent Cassel), who took part in the unrest, and Hubert (Hubert Koundé), a boxer whose gym was wrecked by the rioters. With nothing productive to occupy their time, the three spend the day sitting around the estate chatting, interacting with their respective families, hanging out on the rooftop with other estate residents, chasing off a TV crew looking to make headlines out of the previous night’s disturbance, attempting to visit Abdel in hospital, and dropping in on agitated dealer in stolen goods Darty (Edouard Montoute), whose car has been burned in the previous night’s chaos. Eventually they elect to take a train ride into Paris with the aim of collecting money owed to Saïd by excitable coked-up dealer Astérix (François Levantal). During the course of their conversations it is revealed that one of the policemen lost his gun during the course of the riot, which is now in the possession of the angry and vengeful Vinz, who carries it with him and talks about using it to kill a policeman if Abdel dies.

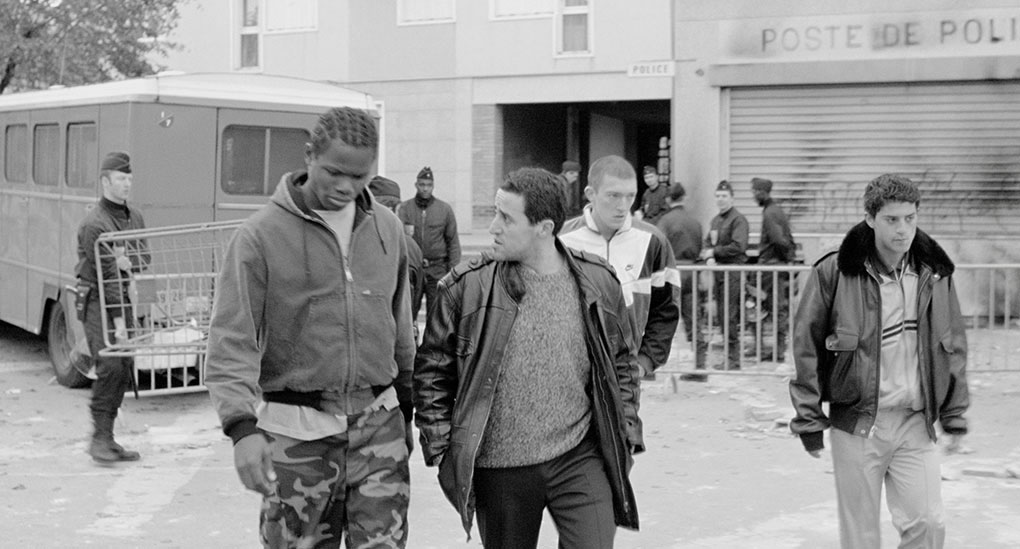

La Haine begins metaphorically as the voice of Hubert tells the above quoted joke about how it’s not the fall that you have to worry about but how you land, and the Earth is hit by a tumbling Molotov cocktail. Film convention is then usurped when what would usually be the detailed end credits play out as the opening titles instead, under which documentary footage of real Paris street riots plays out to Bob Marley’s Burnin' and Lootin'. The sequence concludes with a scene-setting news report on Abdel’s assault and condition, which is switched off mid-sentence and replaced with a black screen and a ticking clock time stamp, a clear signal that something significant is eventually going to happen. This then cuts on the loud ring of a single gunshot to a pristine monochrome shot of Saïd standing in front of the housing estate with his eyes closed, one that dollies smoothly up to his face as he opens them. The camera then switches sides and repeats the movement, this time rising over the back of the still motionless Saïd’s head and shifting focus to reveal a confrontational line of police, vehicles and dogs being unhappily observed by handful of estate residents standing behind a line of erected barriers.

In these opening minutes, Kassovitz lays out the film’s sociopolitical intentions and usurps expectations in rejecting the faux-documentary aesthetic of neorealism and kitchen sink drama in favour of a visual style that is simultaneously striking and yet somehow also true to its subject. For the most part, there are no handheld verité shots here, with the 24-hour journey undertaken by Saïd, Vinz and Hubert observed in beautifully composed static shots and smooth dolly moves. Oh yes, and the entire film is in black-and-white. An arthouse movie, then? Not a bit of it. Artistic, yes, in that all great film should be considered art, but also gripping, entertaining, deeply troubling, confrontational, and – newcomers may be surprised to learn – often genuinely and deliberately funny. But La Haine exists primarily to throw punches that it refuses to pull, and when those blows land you can feel every kilogram of the anger with which they were delivered.

Key to audience engagement here are three terrific central performances from relative newcomers Saïd Taghmaoui, Vincent Cassel and Hubert Koundé as the North African Saïd, the Jewish Vinz and the Afrocaribbean Hubert, each of whom is introduced in creative and character-defining fashion. Their names are even captioned, not with on-screen text but dietetically via details in the film’s mise-en-scène, with Saïd identified by the “Fuck the police” tag that he draws and signs on the back of a police van, Vinz by the nameplate knuckle ring he wears on his left hand, and Hubert by the promotional boxing poster on the wall of his wrecked gym. Their varying personalities are also quickly established, Saïd as a loudmouthed joker with a fondness for relating tales of his conquests and exploits, Vinz as an energetic ball of excitable anger, and Hubert as an often introspective thinker and probably the most level-headed of the three. This diversity not only torpedoes any attempt by an audience to pigeonhole the trio along racial, religious or even personality grounds, but is also accurately conveys how people with seemingly little in common can be united by their social situation against the forces being directed by the state and its wealthy paymasters to keep them down.

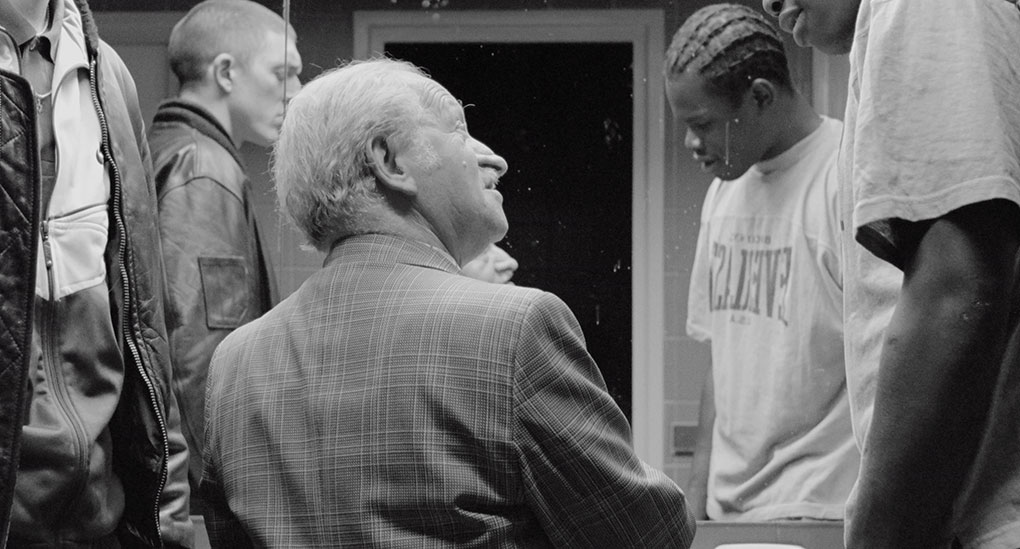

Kassovitz has stated repeatedly in interviews that the film is not anti-police but against a system that allows police brutality to propagate, a claim reinforced by two key scenes in the film. The first comes when Saïd is arrested after he, Hubert and Vinz kick off at the hospital after being refused permission to see their now comatose friend. As Vinz and Hubert risk arrest themselves by continuing to angrily protest, no-nonsense French-Arabic detective Samir (Karim Belkhadra) forcefully intervenes, then drives Vinz and Hubert to the police station – which was also ransacked in the previous night’s riot – to secure Saïd’s release. It becomes clear that Samir used to have a strong relationship with the kids on the estate but feels now that he is fighting a losing battle. He certainly appears to command a degree of respect from Hubert and Saïd – tellingly, Vinz, who at this point still carrying the secreted gun, is the only one who declines to shake his hand when he parts company with the trio.

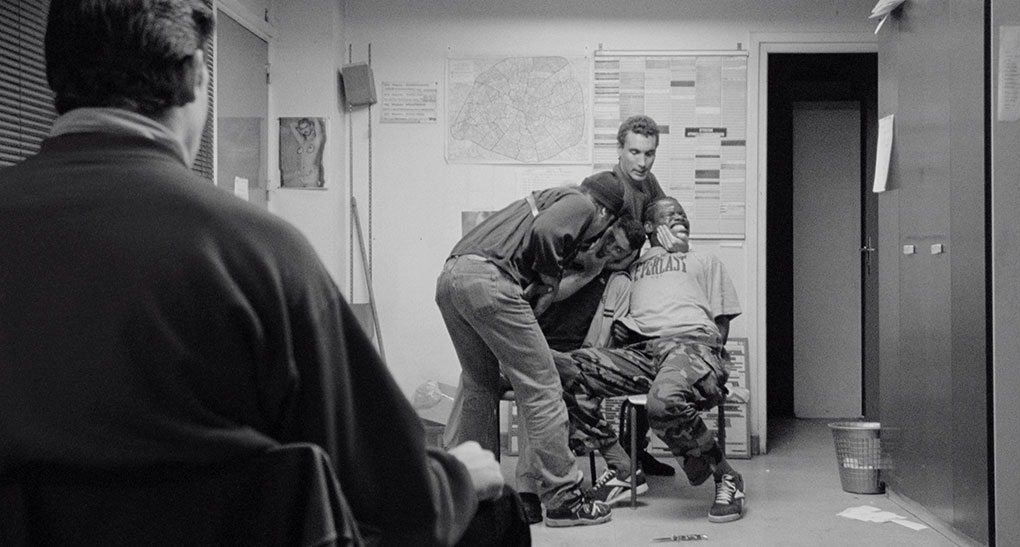

This message really hits home after the three leave the upmarket apartment building in which Astérix is house-sitting. The police are lying in wait outside, presumably having been called by the building’s other wealthy (white) occupants, and instantly pounce on Hubert and Saïd but make a less aggressive effort to restrain Vinz when he attempts to slide out behind them, which allows him to break free and make a successful run for it. The scene that follows is the toughest in the film to watch but is crucial to the point Kassovitz is trying to make and is backed up by plenty of documented real-life cases. Saïd and Hubert, both handcuffed to wooden chairs, are effectively tortured by two of the arresting detectives for their own amusement, one of whom pauses briefly between assaults to cheerfully explain to a new young third member of their team how to carry out these abusive techniques. Each shot of this watching junior detective is telling, from the barely concealed disbelief lurking just beneath his coldly troubled expression to the small despairing shakes of his head and the look he shares with Hubert as the session draws mercifully to a close, brief eye contact that shame forces him to be the first to break. We’re left to ponder on whether he will eventually develop the courage to make a stand against such practices or end up so brutalised by them that he becomes the very thing he seems to (too) quietly despise.

Counterbalancing these scenes is a strain of intermittently bizarre but primarily character-based humour that springs from encounters that Vinz, Saïd and Hubert have over the course of the film’s 24-hour timeframe. These include the hyperactive Astérix with his whirling nunchucks and Russian roulette trickery, an elderly Russian Jew (Tadek Lokcinski) who emerges unexpectedly from a toilet cubicle to relate a lengthy tale of being unable to take a shit when being transported to Siberia with a friend in a cattle car (“Why’d he tell us that?” asks a mystified Saïd after the man has departed), and the trio’s bumbling attempts to steal car whilst being advised by a cheerful passing drunk (Vincent Lindon) who has taken an enthusiastic interest in their endeavours. There’s an almost Buñuelian moment involving a cow that only Vinz sees, and touch of class war metaphor when the three miss the last train home from Paris and drop in on a late night exhibition of avant-garde art, where they help themselves to the buffet food but soon come in conflict with the middle-class guests and organisers before making a noisy and defiant exit.

Strong though the film’s content is, a key reason why it is so impactful is down to how beautifully it is shot, directed, sound mixed and edited. Kassovitz admits in the special features that he dislikes cutting between shots and favours covering sequences in single takes, which are executed here with real artistry through impeccably framed, often deep focus static shots and fluidly executed dolly and Steadicam moves. The second half switch to longer lenses and a shallower depth of field when the three men reach Paris was apparently a pragmatic decision forced by budget restrictions, but this subtle visual shift gives the two halves of the film their own distinct identity without breaking the overriding stylistic continuity. This subtle style switch is triggered by one of the most celebrated shots in the film, a dolly-zoom of Hubert, Vinz and Saïd on a balcony with the bustling Paris in the background that retains the framing whilst dramatically shifting perspective and greatly narrowing the depth-of-field to remind us to focus of the film is these three young men and not on the famed city that they are visiting. Equally championed (much to Kassovitz’s irritation, as he was not completely happy with the result), is the aerial shot that seems to float over the housing estate to the hip-hop mix being blasted through a speaker by the resident DJ (played by real-life DJ Cut Killer). What always struck me about the shot was not its bravura technical execution but that it feels as if the camera is being carried through the air by the sound waves of the DJ’s mix, almost as if we could see as well as hear the music as it washes over all apartments and residents of the estate.

La Haine is one of those rare, special films that it is difficult to say a single original word about, so extensively has it been analysed and studied and written about over the 30 years since it exploded onto cinema screens across the world, and I’ll freely admit that I’ve just skimmed the surface of what makes it such crucial and thrilling cinema. I first saw it when we screened at the cinema based film society that I used to run, by when it had already won Kassovitz the Best Director prize at Cannes, the award for Best Film at that year’s Césars, and become the most talked about French film of the year. It played to a packed house, and the buzz of positive discussion amongst our patrons afterwards was electrifying. Perhaps my favourite comment, and the one that has stayed with me, came from a friend who grew up on a London housing estate with its own share of issues, when he memorably remarked, “That gun was like a bomb waiting to go off the whole way through the film.”

From that thrilling first cinema viewing to this new UHD release, I’ve had absolutely no qualms about this charged, confrontational, superbly performed and brilliantly made film. It remains a towering achievement for such a young filmmaker, one of the genuinely great works of late twentieth-century cinema, and one whose underlying message in these days of fascist populism and increasingly militarised police forces (I’m looking at you, America) feels even more frighteningly relevant than ever.

To quote the presentation notes in the accompanying book, “La Haine has been restored in 4K resolution using the original 35mm camera negative by Le Pacte and Hiventy, with the supervision of director of photography Pierre Aïm. It is presented here in High Dynamic Range with Dolby Vision in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.” The resulting UHD image is everything you would hope it would be, a pin-sharp, gorgeously detailed monochrome 4K transfer with fabulous grading of the greyscale contrast. La Haine was always a great looking film but not since its original cinema release have I seen it looking as good as this, and with no trace of wear or dust and the picture completely stabilised in frame, in some ways it looks even better here. A fine film grain is visible, but is nowhere near as pronounced as the subject matter may lead you to expect, and certainly belies the claim I;ve seen made that it was shot in “grainy” black-and-white. A genuinely outstanding job thgat the grabs here genuinely do not do justice to.

The sound mix of La Haine is one of its many strong points, and here it has been mastered and restored using the original magnetic tracks and is presented both in Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround. The original mix was a stereo one, and if you’re looking for authenticity that’s the track to go for, and you’ll have no complaints here – it boasts crystal clarity, a strong tonal range with well-defined trebles and solid bass levels, distinct and appropriately targeted frontal separation, and no traces of wear or damage. The 5.1 track is essentially the same mix, but with ambient sound subtly spread to the rear speakers. Pleasingly, both tracks retain the film’s switch from stereo to mono when the lads head to Paris and the switch back to stereo in the later scenes.

Also included is an “alternative score” by Asian Dub Foundation, which was recorded live at the Royal Festival Hall in London on the 19 January 2025 and mixed by Bernie Gardner at Warm Puppy Studios and is presented here in Linear PCM 2.0 stereo. This is a tricky one for me to discuss as I’m still not sure what the background to the composition and recording of this track was, and my opinion of it thus remains a little mixed. First up, I should state that I’ve always liked the music of Asian Dub Foundation and the score here is up to the group’s usual standard, and the fact that it exists means it absolutely should be included in what is as close as dammit to a definitive disc release of the film. Yet here’s the thing. The reason why I put quote marks around the term “alternative score” – which is how its referred to in the accompanying book – is because the film in its original form does not have a traditional music score, save for the Bob Marley title track and the diegetic music heard within the film. In the special features, Mathieu Kassovitz makes the case for why he did not want a non-diegetic score, and for me the film has always worked perfectly without one. Adding a score, even a decent one, thus flies in the face of those intentions, and for someone who knows and deeply admires the film in its original form, the addition of music where there was previously none simply feels all wrong. It over-emphasises the impact and intention of key moments and pushes you, sometimes unsubtly, towards a specific emotional response in scenes that worked perfectly well without such a push. It practically screams “don’t stand in the way of these boys as they mean business!” as Vinz, Hubert and Saïd walk purposefully down a hospital corridor to visit Abdel, and even adds sinister pulses to the torture scene to make sure that you register that what’s happening here is essentially evil. You’re free to choose which version you prefer, which I applaud, but for me this track – impressive though much of it is if listened to in isolation – severely diminishes the effectiveness of a previously sublime work.

Optional English subtitles are available and are activated by default when either version of the film is played.

This BFI package consists of two discs, one 4K UHD and one Blu-ray, and unlike many such UHD releases, the Blu-ray is not a 1080p replica of the UHD but a separate disc devoted to additional special features. This, I should note, is one of the reasons for my delay in posting this review, as when we requested the review disc, only the UHD arrived, and I quickly realised that a substantial number of the special features detailed in the press release were missing, and thus had to wait until I could secure the second disc to proceed with the review.

It should also be noticed that almost all of the special features here have been carried over from the 2022 BFI two-disc Blu-ray release, and several date back further to the 2004 10th Anniversary Optimum/StudioCanal DVD release, and are thus in standard definition rather than HD.

UHD SPECIAL FEATURES

Audio Commentary

In one of four special features from the tenth anniversary Optimum DVD (technically, it should have been called the ninth, but hey-ho), this English language commentary by writer-director Matthieu Kassovitz is an essential companion to the film. As well as revealing how individual sequences were filmed, he relates the story of 17-year-old Makomé M'Bowolé, who was shot in the head and killed by a police inspector whilst handcuffed to a chair, an incident that triggered a series of riots in France and inspired Kassovitz to write La Haine. Every bit as shocking is the story of Abdel Ahmed Ghili, who plays Abdel Ichaha, the young victim of police brutality that triggers the riot in the film and is seen only in a single photograph featured on news broadcasts. It’s revealed here that Abdel was snatched off the street by police after confronting them about their treatment of his girlfriend, then taken to a basement room on the estate and set on fire, and still bears the serious burn scars that he was left with. Kassovitz outlines how he and his collaborators earned the trust of the people on the estate on which they planned to shoot the film by living there and getting to know the residents for a few months before filming a single scene, and describes the process of making it as an amazing experience. He has some specifics about working with his three leads, reveals that the young boy who has the long speech about Candid Camera was not an actor, that the boys playing skinheads who assault Saïd and Hubert were actually skinhead hunters, explains why a film that he always planned to be black-and-white was shot in colour and processed in monochrome, and affirms that he was determined from the outset to make the film it look as good as possible. He talks about the music played by the estate DJ, the breakdancers, the cow, the story told by the old man in the public toilet, why the time stamp title cards were included, where crew members (himself included) were deputised to play small roles, and so, so much more. A hugely informative and frankly riveting commentary.

Redefining Rebellion (4:47)

Film critic and programmer Kaleem Aftab provides a brief but concise and insightful examination of what makes La Haine such an important and remarkable work, and notes that it shows how the elites use their police enforcers to try and control those who have taken to the streets in protest against them. He highlights how Kassovitz uses the architecture of the estate and the film’s two most celebrated shots to make sociopolitical points, identifies the trio of working-class protagonists as a fighter, a joker and a politician, and opines that, “there is a mischievous celebration of rebellion makes La Haine the most radical film of French cinema.”

Screen Epiphany: Riz Ahmed introduces La Haine (13:54)

In the first of two included special features recorded remotely during the 2020 pandemic lockdown, acclaimed actor and director Riz Ahmed recalls discovering La Haine by chance at a formative age and being blindsided by it, summing up its blend of authenticity and stylish visuals as Raging Bull meets Italian neorealism. He talks about how contemporary it still feels, how revelatory it was to discover that there were films out there about lives like his and people who looked like him, notes that it does not wallow in self-pity or the tragedy of inner-city life and is frequently hilarious, and explores its influence on his own work, specifically the then-upcoming Mogul Mowgli. Evocatively describing the film as “a swaggering, unapologetic, heavily stylish, deeply authentic, and still incredibly powerful and timeless social critique,” he signs off with the advice, “Please watch this film. If you haven’t seen it, it might just change your life.”

Interview with Mathieu Kassovitz (35:26)

Another special feature delivered by Zoom call in 2020, this interview with Mathieu Kassovitz by Kaleem Aftab has surprisingly little crossover with the Kassovitz commentary, and where the same territory is covered it is almost always expanded on here. Kassovitz talks about his intentions for the film and how shocked he was at the way his black and Arabic friends were treated by the police as a kid, how budget restrictions helped to shape how the film was photographed, the reasons why he opted for black-and-white instead of colour, and how flexibility on location helped deliver one of his favourite shots in the film. He reveals that he knew how the film would end and begin before writing the screenplay, outlines how he secured the rights to use Bob Marley’s Burnin' and Lootin' for the opening title sequence, and has an interesting dual view take on the police and security guards who turned their backs on him on the red carpet at Cannes after he won the prize for Best Director. When asked how he felt about the reaction of politicians – including far right candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen – to the film, his response is an instant and rousingly contemptuous, “Fuck ‘em!” Absolutely.

25th anniversary trailer (1:37)

A “coming soon” trailer for the 2020 4K restoration that was the basis for the transfer on this UHD disc, one initially driven by hip-hop before switching to anticipatory time-bomb ticking.

BLU-RAY SPECIAL FEATURES

A welcome inclusion here is a trio of early short films by Mathieu Kassovitz, which can be watched individually or in chronological sequence via the Play All option.

Fierrot le pou (7:35)

A dorky young white man (played by Kassovitz himself) with no talent for basketball repeatedly tries and fails to throw his ball through the hoop at one end of an empty gym. When a similarly aged black girl (Fabienne Labonne) enters for a practice session of her own and starts scoring with almost every throw, the young man tries all the harder, seemingly keen to impress a girl whose arrival he appears to have anticipated and who flashes him the occasional amused but friendly smile. It’s all to no avail, at least until he lets his imagination take over. An object lesson in what can be done with the short film format, a simple idea, and not a single word of dialogue, this 1990 directorial debut from Kassovitz stylistically prefigures La Haine in is use of purposefully framed and smoothly executed dolly shots, and includes an absolute belter in which the camera moves around the young man as he tries to focus his attention for his next shot, and the girl comes into frame far behind him at the exact second that she scores another hoop. The title is clearly a play on Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 Pierrot le Fou, with the translation amusingly switched from Godard’s “Pierrot the fool” to “Fierrot the louse.”

Cauchemar blanc (10:31)

Four racist white men – René (Yvan Attal), J.P. (Jean-Pierre Darroussin), Barjout (Roger Souza) and Berthon (François Toumarkine) – wait in their car as French-Arabic local Farouk (Abderrahmane El Kebir) passes on his moped, then pursue him to a local estate with the intent of doing him serious harm, but bungle their efforts at every turn. Things, however, are not quite what they seem… The racial prejudice and violence that so angered the young Kassovitz and ultimately gave birth to La Haine is tackled in boldly inventive fashion in this 1991 short film, with the racists and their ignorance and illogical prejudices mercilessly mocked, only for a late-film twist to bring home just how dangerous these wretched people and the attitudes that drive them can really be. The message is simple but most effectively and disturbingly communicated – their rhetoric may be ridiculous, but the threat to civilised society that they represent is no joke and needs to be taken seriously. There’s also a nice bit of commentary here about how those witnessing such crimes should react versus how things too often play out instead. The title translates as "White Nightmare," which is deliberately open to multiple readings.

Assassins… (12:17)

The latest in a long line of contract killers (Marc Berman) attempts to initiate0 his younger brother Max (Mathieu Kassovitz) into the family business by involving him in a hit taken out on elderly Mr. Vidal (Robert Gendreu) by his own son, but the inexperienced Max is initially not prepared for what this requires him to do. Made in 1992 and the only film of the three here in colour, this is a structurally simple tale that metaphorically addresses the real world problem of violent behaviour and being passed down through generations and how a callous disregard for the welfare others is often learned rather than natural behaviour. As with the previous two films, it’s very well made and acted, and while retrospective awareness does play a part here, I couldn’t help thinking that it plays a lot like the test run it effectively proved to be for Kassovitz’s 1997 feature Assassin(s), which he expanded on the central concept again cast himself in the key role of Max.

10 Years of La Haine (83:30)

Made in 2005 to mark the tenth anniversary of the film and graded primarily in black-and-white, presumably in partial sync with the film’s visual aesthetic, this French documentary appears to have been adapted for a past UK DVD release (it isn’t on the above-mentioned 10th Anniversary disc), at least if the burnt-in and Anglicised English subtitles are anything to go by (one derogatory comment is translated as “bollocks”). Mastered in standard definition and visually a touch rough around the edges it may be, but it provides the sort of thorough coverage that all films of this calibre should receive. Linearly structured, it explores in considerable detail the background to, writing, preparation for, shooting, and release of La Haine, as well as its acceptance in the Cannes Films Festival, the subsequent flurry of press attention this triggered, its unexpected selection for competition, and Mathieu Kassovitz’s Best Director win. Built around interviews with Kassovitz, producer Christophe Rossignon, actors Vincent Cassel and Hubert Koundé, associate producer Alain Rocca, cinematographer Pierre Aïm, unit production manager Sophie Quiédeville, camera operator Georges Diane, and sound mixer Vincent Tulli, it also includes footage of news stories and TV interviews with Kassovitz conducted after the film’s Cannes selection and release. Inevitably, there is some crossover with the other on-disc special features, but the duplicated subjects are often covered here in more detail or from a different viewpoint, and there is so much that is unique to this documentary that it proves every bit as essential as the Kassovitz commentary and is a consistently arresting and educational watch.

Casting and Rehearsals (18:39)

Handheld video footage of snippets from a small number of casting conversations (they’re too relaxed to be called interviews) and the rehearsal of several scenes, not always with the actors who ultimately played the parts (Kassovitz stands in for Vincent Cassel on more than one occasion). Of interest to see these scenes in their uncooked form before they were infused with the emotion and energy that the actors brought to the performances they give in the film, this one is in standard definition and framed 4:3 with fixed English subtitles.

Anatomy of a Scene (6:37)

A behind-the-scenes featurette focussed on the filming of a single sequence, one that involves a stunt and some practical effects and one you shouldn’t know more about before watching the film for the first time. Kassovitz outlines the practical reasons for storyboarding the sequence in advance, and in a neat confirmation of my friend’s comment about the film, actor Hubert Koundé succinctly describes La Haine as “a film about an atom bomb.”

Behind the scenes (5:53)

A scattergun montage of material of Kassovitz and his three main actors chilling out, goofing around, and chatting to the DV camera operator in the apartment on the estate in which they were living prior to and during the making of the film. The camaraderie between the actors and director is clearly evident, but this seems like it was shot before filming actually started.

Colour deleted and extended scenes (17:21)

A special feature carried over from the Optimum DVD that remains of considerable interest for two very different reasons. The first is the fact that these scenes are, as stated in the title, in colour rather than the black-and-white of the feature. Kassovitz has confirmed that he always wanted to shoot the film in black-and-white, but reveals in the commentary that they couldn’t get the funding to do so. The compromise they eventually struck with funding body Canal+ was that they should shoot the film in colour, and if it turned out well then a black-and-white version would be given the go-ahead, if not then the film would be released in colour. I have to presume that Kassovitz and his cinematographer Pierre Aïm shot the film with that goal of a black-and-white release in mind, and in the 10 Years of La Haine documentary Aïm explains how he was able to create such rich monochrome prints from colour negative stock. No such postproduction processing has been applied to the extended and deleted scenes here, which provides us with a rare opportunity to see how the film would have looked had it been released in colour (spoiler alert – nowhere near as good). The second reason this collection is of interest is, of course, for the content that didn’t make the final cut, which includes: Vinz becoming mesmerised by a homeless man who appears to have died in the street and whom passers-by are completely oblivious to; the police attempting to prevent the estate residents from leaving the building while the mayor tours the area, which inevitably leads to a confrontation; an extension of the nighttime rooftop scene in which Vinz trots through a few philosophical clichés and Saïd fools his friends into thinking he has taken a fatal fall; the full version of the switching off the Eiffel Tower sequence that includes the jubilant yells from the cast and crew when the lights actually go out; shots of all three friends dancing individually and together in front of a graffiti covered concrete wall (in the film we get only a brief glimpse of Vince’s dancing); and an unedited four minutes of those extraordinary breakdancers demonstrating their skills.

Also included is Selected scenes with afterwords by Mathieu Kassivitz (10:11), in which a selection of the above scenes are each followed by Kassovitz briefly explaining why they were cut from the film.

Two short trailers have been included. Trailer 1 (0:29) intercuts The opening image of the Earth being hit with a molotov cocktail and Hubert's accompanying "so far, so good" story with a memorable rapid camera move from later that hurtles towards the trio and ends with Vinz pulling the found gun on the audience. Trailer 2 (0:38) is brilliantly edited selection of very brief snippets from the film set to time bomb ticking that gradually increases in volume and ends with a different loud noise than I was expecting.

80-Page Book

Kicking things off here is a 1995 Director’s Statement in which Mathieu Kassovitz lists some of the things that he hates and cites the incident that gave birth to this film. This is followed by a compelling essay by professor in film studies at King’s College London, Ginette Vincendeau, who draws direct comparisons between La Haine and Ladj Ly’s 2019 Le Misérables (also excellent), looks at their portrayal of life in the French banlieues (suburbs), and discusses the minor role played by women in Kassovitz’s film. Up next is an interview with Mathieu Kassovitz, conducted by Kaleem Aftab for the May edition of Sight & Sound. Unsurprisingly, there’s quite a bit of crossover here with the on-disc special features, particularly Aftab’s video interview with Kassovitz, but the increased detail here means that it reads like an expansion on what was discussed there, which makes it essential reading. Freelance writer and film critic Steph Green then takes an intriguing look at the role played by rap and hip-hop music in the film in an article that was also originally published in the May 2020 edition of Sight & Sound. In a well-researched and detailed article first published in the November 1995 issue of Sight & Sound, Keith Reader explores the portrayal of life in the banlieues in French cinema, after which is a perceptive essay by Kaleem Aftab that focusses on the friendship between Saïd, Vinz and Hubert and the ways in which it is conveyed by the film. Full credits for La Haine are followed by the original Sight & Sound review of the film by Chris Darke and short but welcome interviews with Mathieu Kassovitz, actors Vincent Cassel, Hubert Koundé and Saïd Taghmaoui, and producer Christophe Rossignon from the film’s 1995 press book. As ever with BFI booklets, credits are also provided for the special features and a brief synopsis of each, plus detailed analyses of each of the three Kassovitz short films.

A personal favourite film that I could have written so much more one were it not for the fact that, due in part to external forces, I’m way, way behind on my site work and have a ton of discs screaming out for my attention and demanding to know why I spent so long on this one. I was blown away by La Haine the first time I saw it and that view hasn’t altered one iota in the decades that have passed since that electric cinema viewing. It’s had some decent disc releases over the years, but this combined UHD/Blu-ray package from the BFI is easily the best yet, for the immaculate 4K restoration and transfer, and for the plethora of top-notch special features. It thus gets our highest recommendation.

|