| |

'A real director is at his best when he works with material that reflects his own life patterns. At a film festival, after Pat Garrett had become the latest of his films to be emasculated by a studio, he [Sam Peckinpah] was asked if he would ever make a ''pure Peckinpah'' and he replied, ''I did Alfredo Garcia and I did it exactly the way I wanted to. Good or bad, like it or not, that was my film.''' |

| |

From a retrospective review of Bring Me the Head

of Alfredo Garcia by Roger Ebert, 28 October 2001 * |

There are some actors I'd watch in just about anything. Spencer Tracy is one, and not so long ago I made the case for why Tommy Lee Jones can do no wrong for me, even when he's in films that I otherwise shudder at even the very thought of sitting through. Another is Warren Oates, a hugely talented performer whose rough-hewn features, growly voice and offbeat screen persona saw him pigeon-holed as a character actor from his first screen appearance. But since then he has appeared in enough cult favourites to make his CV read like the programme for one hell of a film festival. Try this lot for starters: Private Property, The Shooting, In the Heat of the Night, There Was a Crooked Man..., Two-Lane Blacktop, The Hired Hand, Dillinger, Badlands, Cockfighter, Race with the Devil, China 9, Liberty 37, The Brink's Job, 1941, Stripes and Blue Thunder. On TV, he had had roles in The Westerner, Have Gun – Will Travel, Wanted: Dead or Alive, Laramie, The Rifleman, 77 Sunset Strip, The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits and Rawhide. His first role in The Rifleman and his single appearance in The Westerner were for a then up-and-coming director named Sam Peckinpah, with whom he later worked on Ride the High Country, Major Dundee and The Wild Bunch. Then in 1974, Peckinpah offered him the rare chance to play the lead role in the provocatively titled, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. It was to be the last time the two men would work together, and the only time that Peckinpah had complete creative control over one of his films.

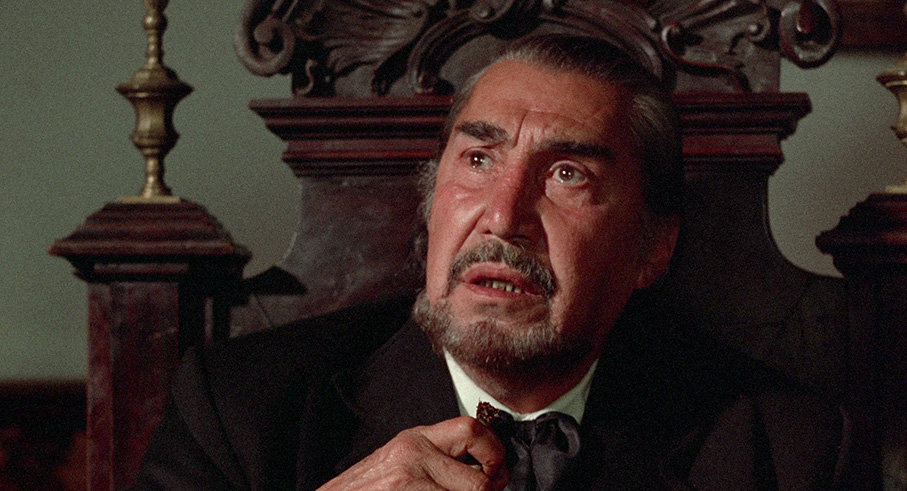

In contemporary Mexico, a powerful rancher known as El Jefe (literally ‘The Boss', played by filmmaker Emilio Fernández, who also played Mapache in The Wild Bunch) orders his heavily pregnant teenage daughter Teresa to reveal the identity of the father of her soon-to-be-born child. Only when tortured does she name Alfredo Garcia, a man whom El Jefe has treated like a son and was grooming to be his successor. El Jefe thus pledges a million dollar reward to anyone who brings him Garcia's head, the long and fruitless search for which leads well-dressed American hitmen Sappensly (Robert Webber) and Quill (Gig Young) to a seedy bar run by retired US Army officer Bennie (Warren Oates). Stonewalled by the locals, they figure they'll have more luck with the gringo manager, and after calmly punching out one of the bar's professional ladies, they slip Bennie a $100 bill and tell him where he can find them, making it clear that they're not interested in locating Garcia alive. As it happens, just about everyone in the bar knows of Garcia, who it turns out has been staying with Bennie's girlfriend Elita (Isela Vega), who reveals to a pissed-off Bennie that he was killed in a drunken car crash shortly after leaving her place. Bennie thus pays the Americans a visit and negotiates a fee of $10,000 to bring them the required physical evidence of Garcia's death, then hits the road with Elita to locate Garcia's body and claim the reward.

There's been a case made by several Peckinpah scholars for seeing Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia as the quintessential Peckinpah film, it being the only one untainted by studio interference (see also the quote at the top). As Stephen Prince observes on his commentary track on this very disc, that doesn't necessarily make Alfredo Garcia his finest film, but it could well be his purest, in all that is good and not so good in that implication. It certainly feels like dangerous cinema, a film that repeatedly refuses to play to expectations or any notions of morality you'll find in standard Hollywood fare. The casting of Oates is a case in point. Peckinpah clearly had no time for good-looking, visually polished or morally upright heroes, and Bennie is the absolute antithesis of all three. A gravel-voiced sleazeball with a colour-blind sense of style who spends much of the film with his eyes hidden behind oversized sunglasses, Bennie has an eye and ear for a quick buck and doesn't care what he has to do to get it. Yet his feelings for Elita – and thus his jealousy at the idea that she may have had a fling with Garcia – appear to be genuine. What he's clearly not so good at is expressing his feelings to her. In the film's most touching and tenderly handled scene, Bennie and Elita take time out from their road trip to picnic under a tree, where they're finally honest about their feelings for each other. We're left with a sense that the marriage proposal that almost has to be squeezed out of Bennie has come a little too late, yet in the very next scene Elita is talking dreamily about sleeping under the stars and making Bennie happy, clearly determined to make the best of the opportunity Bennie's almost reluctant declaration of love presents for them as a couple.

Of course, being just 40 minutes into a 110 minute Sam Peckinpah film, any such celebration of relationship bliss is by default clouded with portent. A short while later this rolls up in the shape of two bikers (played by musicians Donnie Fritts and Kris Kristofferson), who join the couple at camp and pull a gun on Bernie so that one of them can have his evil way with Elita. What follows proves as morally problematic as the rape scene in Straw Dogs, as after delivering two defiant slaps (the second of which is returned in kind), the stripped-to-the-waist Elita not only gives in to her would-be rapist's advances, but even takes the lead in what plays like a protective fall-back to a time when she made her living this way. As a sequence, it makes for uncomfortable viewing, but it also sits oddly in a story in which it has no real narrative role, and is seemingly there only to put the first serious dent in Bennie and Elita's new-found happiness and show that if the situation demands it, Bennie is quite capable of killing without a blink of hesitation.

It's when Bennie and Elita reach Garcia's grave that the film undergoes a tonal and directional shift, and any discussion of this is going take me into serious spoiler territory, but if I'm going to talk about what makes Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia such a crucial Peckinpah film, this cannot be avoided. So, if you're new to the film and want to avoid being hit with a wall of spoilers (including how the film ends) then I'd seriously hop ahead to the final paragraph of the main review. You have been warned.

The process of opening Garcia's grave and preparing his body for beheading is a grim but never graphic or gratuitous sequence, our attention instead focussed on the dark nature and difficulty of the task and its impact on Bennie and Elita, who leads Bennie to the graveside but declines to assist him. Then, just as Bennie is about to decapitate Garcia's corpse, he's knocked unconscious by two Mexicans who are also looking to cash in on El Jefe's bounty, and who have been making such a clumsy job of shadowing Bennie that I began to wonder if the real reason that he was always wearing those sunglasses was because he was going blind. It's here that we get confirmation that the story is being told almost exclusively from Bennie's perspective, as the film loses consciousness with him and fades up with his reawakening, as he rises from the earth in which his attackers have buried him. Bennie somehow survives this ordeal. Elita does not. It's a shocking revelation that traumatises Bennie, stripping him of everything he holds dear and decimating his hopes for the better life that the bounty on Garcia's now stolen head might have brought him.

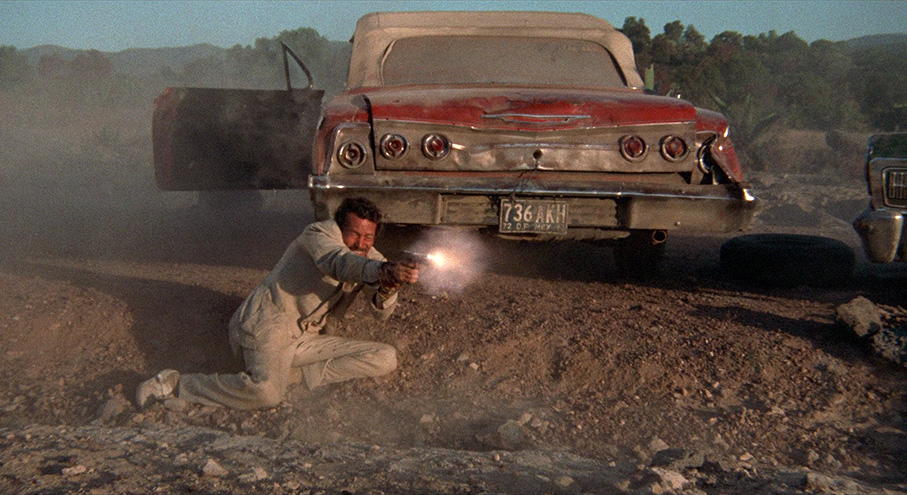

This metaphorical and literal rise from the grave transforms Bennie into an almost unwitting angel of death, his mere presence sometimes all that is required to unleash lethal mayhem on anyone from hired gunmen to a grieving mother and her family. Any expectations that he will spend the rest of the film chasing Elita's killers is quickly quashed when, after angrily stealing a car at gunpoint, he literally drives into their broken-down vehicle and executes both men. This also unites him with the titular head of Alfredo Garcia, which remains concealed from our view in a grubby and fly-pestered bag and becomes in effect Bennie's travelling companion, one to which he intermittently converses and which he fiercely protects in what plays almost like a twisted take on the buddy movie. His quest has become personal, and in the film's most morally complex and startling scene, this brings him into conflict with the gun-toting members of Garcia's family, who confront Bennie over this sacrilegious desecration and demand the head's return. For Bennie, the money has by this point become secondary to his determination to confront the man who first placed the bounty and he even offers all of his remaining money to the family by way of compensation, which they soundly reject. Just how far Bennie will go here to retain ownership of the head – or indeed if he is willing to die here to protect it – is a source of real tension , which is upped by the arrival of Sappensly and Quill, posing as lost tourists and with none of Bennie's qualms about slaughtering Garcia's family. And when the gunfight that follows (a brilliantly staged and layered sequence) leaves Quill mortally wounded, Sappensly's grief-stricken reaction appears to confirm the earlier hints that the two were much more than just partners.

At this point, Bennie still does not know the identity of the man behind the bounty, which forces him first to go through El Jefe's American intermediaries. It's a journey that sees Bennie wrestle with the seven stages of grief and seemingly take a trip back in time, via the tacky modernism of Americans' hotel suite, into a dying past that El Jefe's matriarchal rule of an architecturally timeless compound and his bond with archaic tradition represent. Given the odds against him and the increasingly dark tone of the film, it seems inevitable that this angry lone gunman is set to perish at the hands of El Jefe's small army of protectors, and the fact that he is able to complete his mission and almost make it to freedom did make me wonder if he actually survived being buried alive in that graveyard after all. Do we take his subsequent quest for vengeance at face value, or read it as the fleeting thoughts of a dying man as he slowly suffocates beneath the earth? Or has he figuratively as well as metaphorically risen from the dead to avenge his own murder and that of his beloved Elita? If these seem fanciful readings, it's worth remembering that in Peckinpah's original cut of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, the main story plays out as a flashback memory that flits through the mortally wounded Garrett's head as he falls from his horse.

My first encounter with Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia many years ago was a far from ideal one, coming to it as I did belatedly off the back of The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs, The Getaway and Cross of Iron, all of which had bewitched me not for their violence but their sheer technical brilliance. These were films that turned my understanding of how action scenes could be edited completely on its head, intercutting between simultaneously occurring events and matching slow motion shots to standard speed footage with a fluidity that precious few directors have come close to nailing since. They transformed violent mayhem into exquisitely choreographed ballets of cross-cut imagery and found clarity in chaos, no matter how complex or multi-stranded the battle. As technical exercises alone they were masterclasses, but these films also gripped on an emotional level, as sympathetic characters fought for survival or sacrificed themselves for honour or the bonds of friendship. When I first saw Alfredo Garcia, it was a different story. The film didn't feel as technically slick as other Peckinpah greats and to my then young eyes felt a little ragged and incomplete. It didn't help, of course, that I first caught it on TV at a time when the widescreen frame would have been cropped to 4:3 and the violence probably trimmed. Coming back to the film a good many years later and watching it on a far larger screen, intact and in its correct aspect ratio, the film still had a sometimes ragged quality that I initially found a little distancing, yet two days later I was watching it again, and soon found myself putting other discs on hold for further viewings. And every time I watched the film it just got better, as my eyes were opened to the wealth of intricately packaged character detail, the multiple readings offered by almost every scene, and how each interacts with and impacts on the other. Two further viewings with the commentaries later and I was left wondering why so much of what now seems self-evidently remarkable about this film had passed me by for so long. Yes, there's nothing slick or balletic about the violence here, which instead is desperate and cruel and not in any way cathartic, while its central character is one of the most complex and fascinatingly difficult you'll find anywhere in Peckinpah's cinema. The personal nature of the film is enhanced by the knowledge that Warren Oates based his performance directly on Peckinpah himself, and Oates really is superb here, immersing himself in a role that I genuinely can't imagine many other actors playing with such unrestrained conviction. He's matched at every step by Isela Vega's bewitchingly nuanced performance as the ill-fated Elita, and Robert Webber and Gig Young work small wonders with two roles that on paper were apparently one-dimensional plot functionaries. Over the course of just three revelatory weeks of repeated viewings and re-evaluation, this ragged-edged, confrontational, sometimes difficult and clearly very personal work has gone from being a movie I was never quite sure of to one of my very favourite Peckinpah films. And how often does something like that happen?

Another one of those films that I remember as being visually gritty that has been completely transformed by the 4K restoration and 1080p HD presentation on this Arrow Blu-ray. The image is sharp and the detail crisply rendered, the contrast balance is generally good even on dimmer interiors and often exceptional when the action moves outside into daylight, and the black levels are solid throughout, though do sometimes suck in some surrounding detail in darker scenes. The deliberately drab colour palette is nicely reproduced, and while bright colours are rare, when they do appear – on costumes, car bodywork and tacky hotel décor – they are richly rendered without feeling over-saturated. A fine level of film grain is visible throughout, and there are precious few traces dust spots or damage. A handsome job.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono track is in solid shape without hitting any dynamic highs – there's not much in the way of bass punch, but dialogue, music and effects are clearly reproduced, there's no sign of damage, and no trace of background hiss during quieter scenes.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also available.

If you're planning to read the following in a single session, I'd grab a coffee and a sandwich, as few discs I've ever had the pleasure of reviewing have the sheer number of quality special features included here and I've convered them in some detail. Ready? Here we go.

Sam Peckinpah: Man of Iron (94:15)

Directed by Paul Joyce in 1993, this terrific documentary (which I still have somewhere on VHS tape from when it was originally broadcast) explores Peckinpah's life and film career through interviews with many his key collaborators, and includes archive photos and interview footage, plus to-camera readings from Peckinpah's writings by Jason Robards. This is a warts-and-all work that both celebrates Peckinpah's considerable talent but also explores his darker side, with particular focus on his battles with producers and studios, the personal demons that drove him to drink and drugs, and his treatment of women on and off screen, an aspect of his personality that Joyce does come close to labouring. The director's most loyal associate (and one-time lover) Katherine Haber has some of the most revealing stories (the one in which she nearly took a bullet in the head one night is downright alarming), though it's screenwriter and graphic artist Jim Silke who really seems to get to the heart of what made his close friend tick, and when movingly recalling Peckinpah's final days, director Joyce widely lets him tell the whole story uninterrupted. Scottish screenwriter Alan Sharp (whose credits include The Hired Hand and Ulzana's Raid, as well as Peckinpah's The Osterman Weekend) provides a dissenting voice, while Daniel Melnick appears to be one of the few producers that Peckinpah didn't try to drive off the set and still has good memories of working with him. Some of the best material is supplied by the actors and crew members: James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson discuss a lyrical scene in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid that they had to sneak out and film for free on their day off when the studio wanted to cut it; L.Q. Jones suggests the first assembly edit of The Wild Bunch ran for close to eight hours; editor Garth Craven reveals that he and Peckinpah became so close that the director claimed they were like a married couple; Ali MacGraw admits that she loved Peckinpah but remains eternally glad that she wasn't in love with him; and the extraordinary, fired-up R.G. Armstrong animatedly recalls how the director prompted him to deliver a key scene in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid with the appropriate degree of righteous fury. It's marvellous stuff and the perfect introduction for newcomers to this singular filmmaker and his body of work, though animal lovers will have a small meltdown when producer/screenwriter Gordon Dawson reveals how the cutaways of chickens being used for target practice at the start of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid were filmed.

|

|

The 'remastered' version of the documentary (left) and the original aspect ratio (right) |

It's worth noting that although the film was shot on 16mm film and originally broadcast in the then standard TV aspect ratio of 1.33:1, the content has been cropped and reframed here to (almost) fill the widescreen 16:9 frame, which also softens the image somewhat. This is not a practice I'm remotely fond of, but thankfully much of Joyce's interview material was shot wide enough to accommodate this without cramping the picture, and many of the film clips have been replaced with screen-filling HD upgrades of the same. The name caption graphics also appear to have been given a garish makeover.

The John Player Lecture: Sam Peckinpah (47:23)

An audio-only recording of an interview with Peckinpah conducted at the National Film Theatre shortly after the release of The Wild Bunch. As tended to be his way when interviewed, Peckinpah talks slowly and deliberately with sometimes extended thoughtful pauses, though he does loosen up as the talk progresses and even provides a couple of light-hearted responses to questions in the later stages (when asked how he created the effect of bullets hitting actors and spraying blood, he responds, "We shot them. A little brutal, but…"). And there's some great stuff here, as Peckinpah discusses the thinking behind a memorable sequence at the start of the film, the importance of wardrobe to the characters and the tone, the thinking behind his use of slow motion and his early experiments with the technique, his concern that cuts made to the film would make the violence more appealing, his frustration with producers, becoming typecast as a director of westerns, and a good deal more. Early on he is comically dismissive of Warren Oates, describing him as "that shabby actor" and claiming that he tries "to get as far away from him as possible," only to then reveal that Oates is in the audience with his (then) English wife Vickery Turner. I also learned here that Peckinpah was a big fan of Alain Resnais' Last Year in Marienbad. It's sometimes a struggle to hear the questions, despite the effort that's been made to boost their volume, but you still get the drift of what was asked from Peckinpah's responses.

Kris Kristofferson Songs

Four songs written and performed by Kris Kristofferson as part of his interview for Man of Iron, parts of which appear in the documentary itself, here presented in full and in the original aspect ratio. The songs are One for the Money (1:26), Sam's Song (3:03), Slouching Towards the Millennium (4:09), and Sunday Morning (4:01). A treat for fans of Kristofferson's music, less so for those whose tastes do not run that way, but it's still good to see them here.

Commentary by Stephen Prince

Film scholar and author Stephen Prince – whose books include Savage Cinema: Sam Peckinpah and the Rise of Ultraviolent Movies – kicks off this impressively busy commentary with the proclamation that while Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia may just be the ultimate Sam Peckinpah movie because it was made without any studio interference. There's loads to digest here, and the background information, observations and analysis offered up by Prince not only serves as a fine introduction to the film for newcomers, but should give even long-standing fans of the film some food for thought. Areas covered, often in some detail, include the role of religion in Peckinpah's films (which Prince links directly to madness and perversion), the use of mirror shots in this film, its mix of rage and tenderness, its rule-breaking and occasionally ragged editing structure, the use of slow motion and sound effects, changes made to the original script, Peckinpah's hatred of Richard Nixon, how some elements and motifs are reflected in other Peckinpah films, and a plenty more. Background information is provided on the actors, individual scenes are deconstructed in film-school detail, and while he really lays into the biker/rape scene (and I do get where he's coming from), he is full of praise for the tender picnic scene in which Bennie and Elita bare their souls to each other. He salutes the work of Warren Oates and Isela Vega, but lost a whole bunch of credibility points with me by dismissing Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid – my favourite Peckinpah film, at least in its original director's cut – as "a mess." What, seriously? Still a great track, though.

Commentary by Paul Seydor, Garner Simmons and David Weddle

In the second, equally enthralling commentary track, documentary filmmaker and record producer Nick Redman plays host to three key writers on the cinema of Sam Peckinpah: Paul Seydor is the author of The Authentic Death & Contentious Afterlife of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: The Untold Story of Peckinpah's Last Western Film and Peckinpah: The Western Films – A Reconsideration; David Weddle wrote the first book I bought on the director's work, Sam Peckinpah: 'If They Move ... Kill 'Em!'; and Garner Simmons gave us Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage, and was on set for much of the shooting of Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia and even has a small role in it. As you would expect, this is even busier than the previous commentary, as all three men have plenty to say about the film and are sometimes overlapping and complimenting each other. Some of the areas covered include the origins of the film, information on those cast in some of the smaller roles, how the film was a reflection of Peckinpah's battles with studio execs (this film's executive producer Helmut Dantine plays a criminal money man here and is shot by Bennie), the notion that the story is driven almost exclusively by women (this is convincingly argued), thematic similarities to Under the Volcano, and even the thinking behind the gradual soiling of Bennie's white suit. In complete opposition to Stephen Prince, they all praise the biker/rape scene and outline in some detail why they believe it works and its inclusion was justified.

Theatrical Trailer (1:58)

A pretty good trailer that's loaded with spoilers, and even includes the film's final shot.

And that's just the first disc. If you're debating whether to buy the currently available Limited Edition of Arrow's Blu-ray release of the film or hanging on for a standard Blu-ray release that may never appear, then disc 2 of the Limited Edition release should make your mind up for you. This, good people, is one of the key reasons that this review is so late in arriving, as when I popped the second disc into my player I genuinely had no idea of just how much content I was going to have to watch to write about it with any authority. And this was content I loved watching. Indeed, I'm willing to go out on a limb and suggest that it collectively constitutes one of the best special features I've ever seen on the Blu-ray release of a single film.

Few clues are provided to the extent of the material included here from the disc's static menu, which suggests that there is only one special feature here, a director's cut of Man of Iron. Well, it is and it isn't. You're offered the choice of playing this cut or exploring its contents, and neither will initially reveal just how much has been put onto this disc. In a self-filmed introduction, director Paul Joyce explains that much of the interview footage that he shot didn't make it into the 94-minute cut of Man of Iron, and while this is far from unusual, instead of discarding the unused footage, he transferred all of the rushes onto Beta video tapes that he kept hold of through eight house moves and three marriages. The good people at Arrow were unsurprisingly excited by this news, and had all the tapes – which were still in fine shape – transcoded into high definition video files. And they're all here, in their unedited form and original aspect ratio (which also means they are visually sharper than the enlarged enlarged material used in the 'remastered' version of Man of Iron), complete with off-camera questions and the occasional restart, and collectively they run for close to 9 hours. Yes, you read that right. But there's more. There's also a brand new, 43-minute interview with actor David Warner, a nine-minute interview with director Paul Joyce, and a newly shot, 8-minute introduction by Katherine Haber, who also provides new 2-3 minute introductions for each of the archive. That's over 10 hours of material on this one disc alone. 10 hours! If that seems intimidating, know that the interviews themselves are all compelling and revealing, and while some of the material here is in the documentary, so much more is not.

To give you a taste, I'll list the interviews in the order they appear on the disc, and highlight a few of the areas covered in each that did not make into the broadcast cut of Man of Iron.

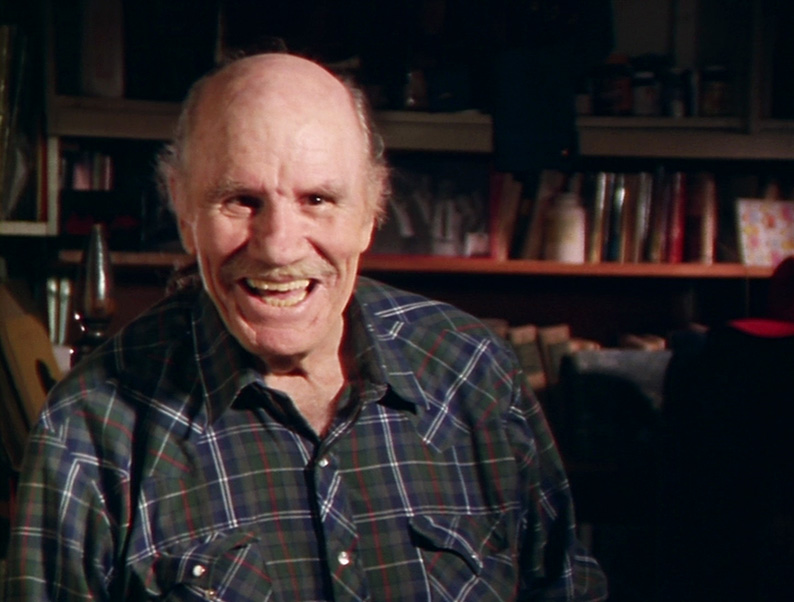

R.G. Armstrong (30:47)

So fired up was Armstrong in the documentary that I was seriously excited by the prospect of seeing more of this interview, and it doesn't disappoint. The actor talks about his work on Major Dundee, tells a wonderful story about a chicken wrangler hired for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, recalls Peckinpah's stock cast members being described in the press as his "walking wounded," enthuses about the way Peckinpah could prompt actors to stretch themselves, remembers seeing him throw rocks at producers, and says of the excitement of working with the director, "We were like the Wild Bunch when we shot a fucking movie!" He's also one of several interviewees who impersonates Peckinpah in loudly confrontational mode.

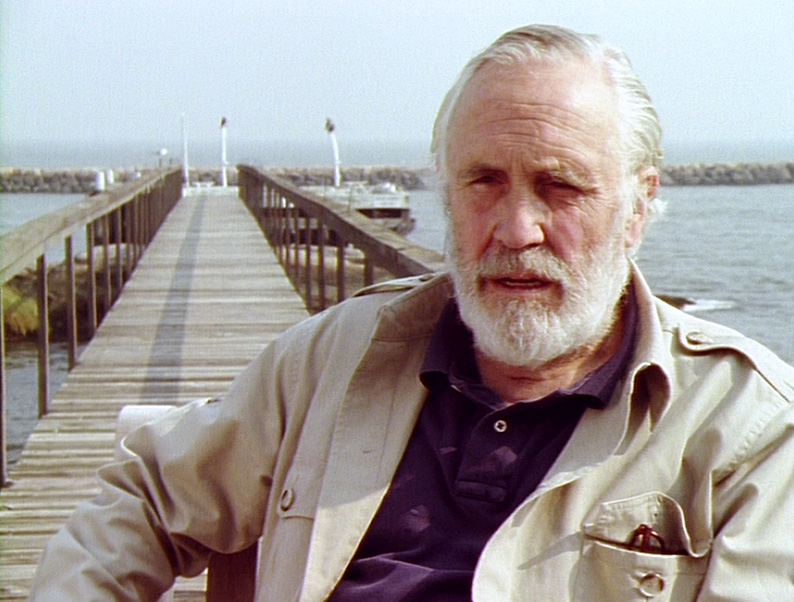

James Coburn (39:10)

The laid-back and wonderful growly-voice Coburn recalls first meeting and working with Peckinpah on Major Dundee, reveals how the sequence in Pat Garrett in which he shoots his own mirrored reflection came to be, talks about researching film archive material with Peckinpah in preparation for Cross of Iron, dismisses Convoy as "a disaster to begin with" and a film that was "based on a terrible song," and remembers balling out a producer on the set of Cross of Iron, a move that made producer-hating Peckinpah smile. Particularly engaging are stories he tells about when Peckinpah met Federico Fellini, and when peckinpah dazzled the Japanese by writing haiku at a party hosted by Toshiro Mifune. He also states emphatically, "Sam made a film, he didn't shoot a script."

Garth Craven (20:16)

Peckinpah's regular editor recalls first working with the director on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, identifies Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia as one of Peckinpah's most personal films and one that he as an editor is most proud of, and confirms that the making of Pat Garrett was a crisis from beginning to end.

Gordon T. Dawson (31:22)

Dawson recalls his first job for Peckinpah ageing the costumes on Major Dundee, and how his wardrobe duties on The Wild Bunch prompted Peckinpah to help him to become a screenwriter and producer by way of thanks. He's one of many who comment on the director's phenomenal attention to detail (there's an engaging story involving a donkey and vultures to illustrate this). "There's nothing sadder than to see Sam without a picture," he remarks. "It was a king without a kingdom."

Michael Deeley (9:49)

A brief chat with Deeley that expands on the material included in the documentary and does include a couple of revealing gems, my favourite being that when he budgeted Convoy, he included a fund to cope with "some degree of chaos" based purely on Peckinpah's past reputation.

Katherine Haber (51:19)

Unsurprisingly, this is one of the most extensive interviews here, and is packed with interesting titbits that didn't make it into the documentary. The tone is set by the news that her move to the US following her work on Straw Dogs was initiated by a phone call from Peckinpah ordering her to "get your fucking arse over here," there's plenty on his unpredictability and knack for keeping everyone on their toes, and the hidden mic story from the documentary has a creepy postscript here. She still remembers working with him as a wonderful time and a great learning experience.

Monte Hellman (30:56)

Hellman remembers being asked to help with the editing of The Killer Elite after Peckinpah had seen and been impressed by Hellman's directorial debut, Two Lane Blacktop, and how despite being in an almost constant drunken stupor, Sam would still have brilliant ideas after watching the edit at the end of each day. His discusses his (uncredited) work with Rudy Wurlitzer on the script for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, directing Peckinpah in China 9, Liberty 17, and there's an amusing tale a botched attempt to hook Peckinpah up with Federico Fellini – in his own interview, James Coburn outlines how the two directors did finally meet.

L.Q. Jones (42:17)

The lively and upbeat L.Q. Jones describes Peckinpah's films as being about people who have outlived their usefulness, and talks about the way he handled actors and technicians and how everyone acts to a different carrot (others also talk about him knowing how to push each person's button). He reveals (to my considerable surprise) that his three-time film partner Strother Martin was terrified of Peckinpah and includes an anecdote to illustrate this, and cannily predicts that a few years from now film scholars will be rediscovering and championing the director's work. How about that?

Kris Kristofferson (36:43)

Strapped to a guitar that he intermittently plucks, Kristofferson suggests that he and Peckinpah hit it off from their first meeting in part because they were both drunks, suggests his role as the biker/rapist in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia was to the detriment of the film, and reveals that Peckinpah visited the set of Heaven's Gate, another film that was recut and ultimately wrecked by the studio that funded it. There's a telling moment when an off-screen Paul Joyce says, "Can we talk about Convoy," and Kristofferson groans an involuntary, "Oh God..." and he reveals that he has always identified with Peckinpah and even saw him as an older version of himself.

Ali MacGraw (31:32)

An engaging Ali MacGraw is open about the speed with which her relationship with Steve McQueen developed on The Getaway, how McQueen and Peckinpah understood each perfectly, how Peckinpah reacted when she was unable to pull off a reaction to something she couldn't see, and the fact that she has stronger memories of him than of her own father. Convoy gets another caning here, being dismissed by MacGraw as "a dreadful movie," and despite hating the way Sam treated people who irritated him and the effects drink and drugs had on him, she still has great affection for a man who "became part of my life at a very difficult period."

David Melnick (41:26)

Producer David Melnick provides some useful information on the prep and development of Straw Dogs, reveals that the completion bond guarantors had director Peter Collinson (he of The Italian Job and Fright) waiting in the wings to replace Peckinpah if he should screw up, and that Susan George became terrified of doing the rape scene and would only do so if Melnick was present at all times – it's nice to hear that after half a day's shooting he was no longer required, so relaxed was everyone about the scene by then. Peckinpah's love affair with alcohol is recalled as one of the film's problems ("Sam's idea of not drinking was only to have wine before breakfast"), and there's an entertaining anecdote about how Peckinpah used to wind up the editor by demanding a shot that they would swear they didn't have and then instantly finding it where he'd planted it earlier.

Bob Peckinpah (17:55)

Peckinpah's cousin Bob expands on the family history lesson he provides for the documentary and admits to being proud of Sam's talent, and pleased that his fame means that everyone now knows how to correctly spell the family name.

Jason Robards (27:21)

This is a choice addition, as none of it appears in the documentary, where Robards becomes Peckinpah's mouthpiece and reads from his letters instead. Unsurprisingly, the focus is on The Ballad of Cable Hogue, but Robards also discusses first working with Peckinpah on the TV drama Noon Wine and reveals that it was Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn who first made him aware of his work as a director. It was he that introduced Peckinpah to Sergio Leone (whom Sam then pissed off by stealing one of his girlfriends), and he was apparently best man at Robards' wedding, where this director of tough westerns was apparently reduced to tears.

Tom Runyon (3:54)

The owner of a restaurant regularly frequented by Peckinpah, Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw has a brief but jovial conversation with MacGraw about his small role in The Getaway and delivering one of the film's most memorable lines.

Mort Stahl (32:19)

Satirist Mort Stahl gripes a bit about liberal values but still has some interesting things to say, and it was his production company that tried to set up the film adaptation of James Gould Cozzens' Castaway that Peckinpah had wanted (and was slated) to direct. Stahl was also originally slated to play one of the American hit men in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia – personally I'm more than happy that Robert Webber and Gig Young landed those roles.

Alan Sharp (30:16)

The Osterman Weekend screenwriter Alan Sharp takes a dim view of Peckinpah's behaviour towards producers, recalls working with him on a script that he wasn't particularly happy with in the first place, and comments on their lack of rapport, the poor state of Peckinpah's health and his obsession with keeping transcripts of everything that was said, just in case... Although largely down on Peckinpah the man and the purveyor of what he regards pathological violence, he does later describe him as "a wonderfully fluent filmmaker" and a dynamic editor, and makes comparisons to David Lynch in this regard.

Jim Silke (50:18)

As someone who was close to Peckinpah right up to his last days, Silke has plenty of engaging stories and observations that didn't make it into Man of Iron. I learned here that Peckinpah was fired from The Cincinnati Kid for shooting nudity, that making a movie was as important to him as the movie itself, that the grumpy vagueness of his interview persona was generally put on, and that Silke set his kitchen on fire because he was becoming so immersed in the lead character when writing Castaway. There's lots more of interest here.

Robert Visciglia (19:32)

Visciglia, who comes across here as a Mafia Wise Guy, tells an interesting tale about his memorable first meeting with a post-punch-up Peckinpah and claims that he never gave actors specific direction but found ways of setting them up to play the sequence the way he wanted (this is repeated several times elsewhere). He also recalls how much he was hurt by Peckinpah's decline, because "His talent was my friend," and backs up another widespread claim when he remarks that Sam loved making films – "You couldn't get the camera away from that man."

David Warner (42:45)

This new interview with David Warner is a most welcome addition, in part because Warner worked with Peckinpah on three films, but also because he is such an engaging interviewee. The tone is set by the story of how he was cast in The Ballad of Cable Hogue but nearly lost the job because of a panic attack about flying, only to have Peckinpah go to great lengths to get him there by alternative means and even hold up filming for a couple of weeks until his arrival. He explains why he is not credited for his crucial role in Straw Dogs and seems to never have had a problem with Peckinpah, saying of their working relationship, "He was always very gentle with me." He also suggests that the director didn't ever seem to know how to end his films, and confirms a story told elsewhere that the ending of Straw Dogs was improvised by Dustin Hoffman and himself. He even shows the medal he was given by Peckinpah for his work on Cross of Iron – these film completion medals are mentioned in other interviews, so it's nice to actually see one.

Paul Joyce (8:34)

In a newly shot interview, Joyce outlines in more detail than in his introduction how Man of Iron came to be made, and reveals that he knew Peckinpah and almost worked with him – for a while Joyce had the rights to what later became The Wicker Man, and the idea that Peckinpah might have been that film's director plays mad games with my head.

Also exclusive to the Limited Edition is an extensive collector's Booklet containing new writing by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and numerous reprints including interviews and more, but this was not available for review.

Peckinpah's most personal and unmolested film is in some ways his most challenging but, if you give it a chance or three, is also one of his most rewarding. Just as The Wild Bunch and The Getaway were great studio films, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia has all the hallmarks of inventive and risk-taking independent cinema. To see it restored to this quality would alone be cause for celebration, but Arrow have not just gone the extra mile with this superb Blu-ray, they're run around the world and swum all of its oceans. Seriously, how many single-disc releases can you think of that boast over 15 hours of extra features, including two excellent commentaries and a lorry-load of enthralling interview material? This is a brilliant release that comes with our very highest recommendation.

* http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-bring-me-the-head-of-alfredo-garcia-1974

|