|

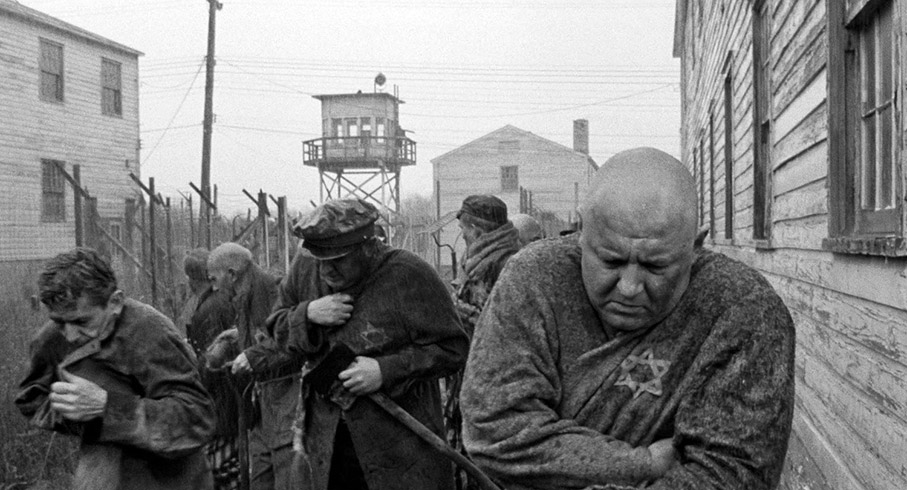

New York City, the early 1960s. Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger) runs a pawn shop in East Harlem. Haunted by his memories of his time in a concentration camp and the deaths of his wife and children, he seals himself off from all but basic human contact. But this cannot be sustained for ever...

The Pawnbroker, written by Morton Fine and David Friedkin from a novel by Edward Lewis Wallant, is a film of definite significance other than simply through its merits, which are considerable. It shows Hollywood filmmaking at a point of change, not just in the way films were made but in terms of subject matter and how that subject matter could be treated, for an adult audience. That doesn’t always translate to commercial appeal, and The Pawnbroker struggled to find an audience. There’s no doubt that it’s a tough watch. But it remains one of the peaks of Sidney Lumet’s long and prolific career, and also of Rod Steiger’s.

Lumet had begun as an actor before moving into direction after his War service, at first on stage then from 1950 in television. He crossed over to the big screen with 12 Angry Men in 1957. The Pawnbroker was shot six years later (29 September is a Saturday in the film, so the film is set in 1962). Throughout his working life Lumet took on commercial assignments as well as more personal work, and with so many films there are inevitably a number of duds. (In the booklet for this release, Jim Hemphill singles out 1974’s Lovin’ Molly, and it’s fair to say that his MPAA X-rated 1968 Tennessee Williams adaptation Last of the Mobile Hot Shots (aka Blood Kin) has vanished into obscurity – it may never have been released in the UK.) But even eight films in, several of Lumet’s hallmarks were already in place: an emphasis on almost-documentary realism, often based in his native New York City (he was born in Philadelphia, but grew up in the Lower East Side of Manhattan). His filmmaking style tended to the self-effacing, sometimes deceptively so, and often in the service of his cast. He was one of the great directors of actors in American cinema, and you’ll never, or almost never, find a bad performance in any of his films, from the leads to the smallest bit parts. His films often tackle sometimes difficult issues. This sometimes brought him into conflict with the censors, of which more later.

While Hollywood films had tackled the Holocaust before – The Diary of Anne Frank, for example, or Judgment at Nuremberg (which included actual concentration camp footage, which Lumet declined to do) – The Pawnbroker was the first to deal with the subject from the point of view of a survivor. Nazerman is a broken man from what he went through, some of which we see in flashbacks. The film shows him beginning to make connections with other people again, even if the result is more pain. The film isn’t remotely sentimental about this, and Nazerman isn’t played for easy sympathy. It’s a tribute to Steiger, and the make-up artists, as to how convincing he is in the role, given that he was in his late thirties when he made the film. Without the ageing makeup, he plays his younger self in the flashbacks. His final soundless scream was modelled, Steiger said, on Picasso’s Guernica. Steiger regarded this scene as possibly his greatest work as an actor, and says so in the interview included on this disc.

Steiger was attached to the film from the start. Arthur Hiller was one of the directors initially attached before Lumet came on board. (Stanley Kubrick, Karel Reisz and Franco Zeffirelli, strangely enough, were among the others offered the film.) Lumet had worked with Steiger before in television and initially favoured James Mason for the role. He feared that Steiger was too larger than life as an actor to play Nazerman, but fortunately Steiger reined himself in, all the best for this film.

That almost-documentary realism is to the fore in The Pawnbroker. While Nazerman’s shop is a studio set (designed by Richard Sylbert with much emphasis on bars and grilles, emphasising Nazerman’s entrapment), there are scenes shot on the real streets of New York, sometimes with, you suspect, hidden cameras. Although Lumet had made one film in colour (his second feature, Stage Struck, 1958), The Pawnbroker was, like all of his other films to date, shot in black and white. Boris Kaufman, who had shot four of Lumet’s previous features, turns in exemplary work. By 1963, when The Pawnbroker was shot, there was still a sense that black and white was more suited to more realistic subjects, due to the ability to use closer to natural light and without the types of saturated colours more appropriate to historical epics and musicals. However, during the mid-1960s as country after country’s television services began broadcasting in colour, black and white – at least in English-language studio pictures began to decline. Lumet clearly favoured monochrome, and used it as long as he was able to: his next film, The Hill (1965) was also black and white. He wanted to make The Deadly Affair (1966) in black and white, but Columbia vetoed that, so cinematographer Freddie Young shot the film in muted, sometimes monochromatic colour, by “flashing” (pre-exposing) the film.

Another wind that was blowing in filmmaking in the 1960s was the influence of the French New Wave. Lumet, and his editor Ralph Rosenblum, convey Nazerman’s memories by means of jagged “flashes”, sometimes only a couple of frames long. At four points in the film, these initial flashes expand into extended flashbacks. This technique was avowedly influenced by the films of Alain Resnais, in particular Hiroshima Mon Amour. (Resnais used the same technique in Muriel, which premiered in the USA at the New York Film Festival about a month before The Pawnbroker started shooting, so it’s possible that Lumet might have seen it.) One of these flashback sequences was the reason for the difficulties The Pawnbroker had with the censors.

You can see nudity, often but not always fleeting, in later silent films (such as the very first Best Picture – or “Best Production” as it was then called – Wings) and in some of the films of the Pre-Code era. With the enforcement of the Production Code in 1934, such material vanished from the films of the major studios (though not in some films, independent productions which bypassed the Code and went out without its Seal of Approval, such as Child Bride (1938)). By the 1960s, the Code had weathered challenges from directors such as Otto Preminger and Billy Wilder. It seemed less and less fit for purpose, especially in comparison to films from other countries which were able to deal with more adult subject matter without having to sanitise it. And gradually taboos were being broken and in 1967 the Code was replaced with a ratings system. Some taboos were still in place by the time The Pawnbroker was made in late 1963, and some remained there for the time being. (Language, for example: you’d imagine that some of the characters would have used stronger words than they are heard to use here.) The Pawnbroker is notable as one of the earliest American films with characters who are at least hinted at being gay (shown, not told). However, its particular breakthrough happens just over an hour in.

Nazerman’s assistant Jesus Ortiz (Jaime Sanchez) has a girlfriend (Thelma Oliver, billed as “Ortiz’ Girl” in the credits but her character name is Mabel in the novel) who is, the film implies, a prostitute. She works for Rodriguez (Brock Peters) a racketeer who runs the pawn shop as a front and to launder money – something of which Nazerman is (wilfully?) ignorant. Ortiz is trying to raise money to set up his own shop, and Mabel offers herself to Nazerman to earn some more. In this scene, Mabel bares her breasts, and this causes a frenzy of flashbacks to Nazerman’s time in the concentration camp, where he was forced to watch his wife Ruth (Linda Geiser) prostituted to the Nazis, and she too is seen nude. The Legion of Decency condemned the film while acknowledging its merits – their condemnation was in order to deter the makers of less distinguished films from including nudity. After initially rejecting the film, the Production Code Administration finally gave the film its Seal of Approval after minimal cuts, but again it was an acknowledged exception to its ban on nudity. Some Jewish groups urged a boycott of the film as they found it anti-Semitic (and a non-Jew playing the lead role, may not have helped). Black groups thought the film encouraged stereotypes as its black characters are pimps, racketeers and a prostitute.

The Pawnbroker premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in June 1964, winning Steiger the Silver Bear as Best Actor and the film an Honourable Mention the FIPRESCI Prize. However, the film’s content, downbeat as well as controversial, deterred many distributors, and the film didn’t get a US release until April 1965, and it was over a year later that it was released in the UK. Steiger won the BAFTA Award and gained the film’s only Oscar nomination, for Best Actor.

Lumet directed many more films in the remaining forty-three years of his career, in several genres, not all of them successful. Time and again he returned to his home city for inspiration, often dealing with characters on both sides of the law. The Pawnbroker remains one of his major works.

The Pawnbroker is a dual-format release from the BFI, comprising a Region B Blu-ray and a Region 2 DVD. A checkdisc of the former was received for review. It’s now a 15. Among the extras, Ten Bob in Winter is a PG.

The film was shot in black and white 35mm. The Blu-ray transfer is in the correct aspect ratio of 1.85:1 (Lumet never shot a film in Scope). Contrast and greyscale seem spot on, and there’s plenty of filmlike grain and occasional softness seems due to the original shooting.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. The mix is an example of Hollywood expertise, with dialogue, sound effects and Quincy Jones’s score well balanced. English hard-of-hearing subtitles are available. Some German dialogue is intentionally left unsubtitled.

Audio Commentary

This was recorded in June 2021 and features Lumet’s biographer Maura Siegel and Annette Insdorf, writer of Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust, and who lost relatives to the Holocaust. Both women approach the film from their particular areas of interest, but there’s much of interest as Spiegel in particular discusses Lumet’s filmmaking style and production and censorship history. They also point out such things as Morgan Freeman’s screen debut towards the end, as an uncredited extra.

Rod Steiger Interview (112:34)

Steiger was interviewed by Tom Hutchinson on stage at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank) on 23 August 1992, following a showing of The Pawnbroker. Steiger is on entertaining form, beginning by calling out Simon Callow (who had recently directed him in The Ballad of the Sad Cafe and cut one of his scenes out) in the audience, and says “beat that” to Warren Beatty because he had just fathered a child at the age of sixty-seven. However, he also talks about his mental health issues, such as his long-term clinical depression. As with other such interviews when they become disc extras, extracts from some of his films are edited out, and Steiger also asks (not always audible) questions from the audience. This interview plays as an alternative audio track to the main feature, and lasts almost as long as it does, with the film’s audio taking over after it finishes.

Now and Then: Quincy Jones (21:12)

Between September 1967 and June 1968, Canadian-born but British-resident broadcaster Bernard Braden conducted 330 interviews with prominent figures of the day in many different fields, for a proposed television series called Now and Then. The idea was that the interviews would be followed up two years later to see how the subjects’ plans had panned out. The series was never completed or broadcast, and the unedited interviews – shot on 16mm colour film – are now in the BFI National Archive and the BFI have used several of them as disc extras. This time, on 26 April 1968, it was the turn of Quincy Jones.

Jones was in London working on the music for McKenna’s Gold. He discusses his early career, beginning as a teenager when Ray Charles (two years older but still a teenager himself) acted as a mentor. Jones talks about his musical influences and the state of the musical industry at the time. As for his film work, he says that he wasn’t sure that The Pawnbroker needed a music score, but his work is a highlight. The interview is unedited, including the clapper board at the start of each new film reel and it ends abruptly in mid-sentence.

Ten Bob in Winter (12:08)

Another example of a BFI extra that’s not specific to the main feature but relates to some of its themes, more or less tangentially. In fact, this is Lloyd Reckord’s short film’s second appearance at least on a BFI disc: you can also see it on their release of Look Back in Anger, in their Woodfall: A Revolution in British Cinema, one of the major Blu-ray releases of 2018.

Ten Bob in Winter was made in 1963 for the BFI Experimental Film Fund. Some of its experimentalism may have been forced by circumstances: there’s no direct sound, just a music score and narration provided by writer/director Lloyd Reckord. One sequence becomes a series of still photographs. The film was shot in black and white 16mm, and very grainy it is too. The story is a simple one of a ten-shilling (“ten bob”, hence the title) note and its journey through the hands of three men, reflecting on class prejudice in the Caribbean community in West London. Jamaican-born Reckord (1929-2015) was primarily an actor, and in the history books for being one of the participants in the earliest known interracial kiss on British television, in 1959. He was also a stage director but this is one of only two occasions he directed a film. The other was another short, Dream A40, two years later, which the BBFC banned for its gay theme: the kiss this time being between two men.

Image gallery (5:09)

A self-navigating gallery with one poster design, plus front-of-house and production stills.

Trailer (2:16)

A spoiler-heavy effort rather heavy on the quotes, in the hope that the critical notices would draw in audiences to what was clearly a tough sell.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, in the first pressing only, runs to thirty-two pages. There is a spoiler warning at the start, so read it after watching the film if you haven’t seen it before. It begins with an essay by Jim Hemphill, who places the film as one of several of Lumet’s dealing with characters in acute moral crisis and unable to save others, or themselves. There are no easy answers. This is something Hemphill links to an incident Lumet recalled from India when he was there as a GI in 1940. He also suggests that many of Lumet’s hallmarks as a film director were developed in his television work, often broadcast live with multiple cameras, often working on multiple assignments at once. Maura Spiegel provides an overview of Lumet’s life and career. Nicolas Pillai talks about Quincy Jones, from his early career as a musician and arranger, with a brief look at his score for The Pawnbroker, which mixes both jazz and classical motifs. The booklet also includes full film credits, notes on and credits for the extras, plus stills.

A tough film that does not leave the audience with any easy answers, The Pawnbroker is a major film of mid-1960s American cinema, both for its merits as well as its place in the breakdown of film censorship.

|