"We

thought we'd start start slowly and build up to

a crescendo of lies." |

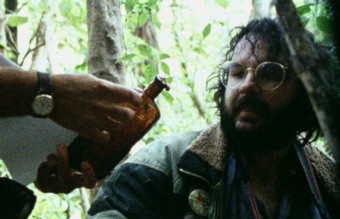

Co-director

Costa Botes |

Being

the victim of a prank can prompt a variety of reactions,

from tolerant amusement to outright anger. Most of us

dislike being deceived, but to be completely and successfully

hoodwinked into believing that something is true and

then be told it's not can actually be humiliating.

The more you believe in what you are told, the more

extreme your reaction to being fooled is likely to be.

Thus when landscape artists Doug Bower and Dave Chorley

revealed that the crop circles that had been appearing

all over the southern counties were made not by visitors

from other planets but by the two of them with a pole,

a rope, a board and a few beers, many of those who had

effectively built their own ludicrous religion around

these seemingly mysterious apparitions simply dismissed

this and continued to believe that at least a sizeable

number were made by flying saucers. A couple

of years back some enterprising English farmers even developed

a nice sideline arranging tours of crop circles that had appeared on their

land for American tourists who were daft enough to take

M. Night Shayamalan's ridiculous Signs

seriously.

On

31st October 1995, a documentary was aired on New Zealand

television that proved something of a revelation. It was sparked

by the discovery of a chest full of film cans by noted

Kiwi film-maker Peter Jackson (yes, he of Bad

Taste, Braindead, Heavenly

Creatures and The Lord of the Rings)

in a shed located in the garden of the house of an elderly neighbour,

film that has been shot early in the 20th century by

an until then virtually unknown film-maker named Colin

McKenzie. At a time when the world was celebrating 100

years of cinema and the good people of New Zealand were being

asked to search their attics and cellars for films that

would shed more light on the country's own cinematic

past, this was exciting stuff. McKenzie was a genuine

innovator, building and mechanising his own movie cameras,

creating his own film emulsion and colour stock, almost

accidentally inventing the tracking shot and the close-up,

and even delivering evidence that local inventor and

aviator Richard Peace was ahead of the Wright Brothers

in the realms of manned flight. McKenzie had even supplied his own sober epitaph

– as a war cameraman, he had laid down his camera to

help and injured man and unknowingly filmed his own

death. But the most extraordinary

discovery was his epic feature Salome – the first film that

truly deserved that classification – which was

uncovered when the programme's co-directors Peter Jackson

and Costa Botes mounted an expedition into the New Zealand

bush to search for the remains of the film's extraordinary

sets.

Astonishing stuff.

Except none of it was true. Jackson and Botes had hoodwinked

much of the viewing public into believing what they

dearly wanted to believe. They were aided in their quest by the authenticity

of their footage, the programme's convincing documentary style, sincere

interviews with established industry figures such as critic Leonard

Maltin, actor Sam Neill and Miramax boss Harvey Weinstein

(who cheerfully announces that he will be cutting an

hour from Salome for its US distribution),

and an accompanying article run in the respected weekly

current affairs magazine The New Zealand Listener. When

the hoax was revealed, the reaction was largely one of

anger at having been so effectively hoodwinked, several

complainants announcing that they would never trust

a television documentary again.

Which

is fair enough, if you think about it. We believe what

we see in a documentary not because it re-enforces information

already known to us, but because we implicitly trust

the genre as factual. Its codes and conventions

mean that a documentary work is instantly distinguishable

from a fictional one, and when the style is used to

present fiction in a documentary way it is usually done

in comedic fashion, making alert viewers aware that the genre is in fact being sent up, as in

Rob Reiner's landmark mockumentary This is Spinal

Tap. Without these comic indicators, however,

all we are left with to distinguish between fact

and fiction is common sense, and there are two problems

here: a) fact can be notoriously stranger than

fiction; and b) modern society is so overloaded with

ridiculous bullshit that a fair proportion of any audience

for any fake documentary will swallow it without question, in much the same way they do the fabricated or ludicrously exaggerated twaddle in tabloid newspapers.

Thus the BBC were able in 1957 to sell the idea of spaghetti

trees as an April Fool joke, and in 1977 Anglia Television

screened Alternative 3 (the very film

that influenced Botes to kick this project off in the

first place), which convinced its audience that personnel

involved in a British space mission had mysteriously

vanished from their homes. Then in 1992, a BBC production titled Ghost

Watch was able to convince its audience that they were watching

live coverage of a poltergeist at work in an ordinary

suburban home. The BBC banned outright The War

Game (1965), Peter Watkins'

devastating look at the effects of nuclear war, on the

basis that it was propagandist, but it seems more likely

that it was the sometimes frighteningly realistic documentary-like

approach that really rattled the corporation's executives. After all, look what

happened back in 1938 when Orson Welles presented War

of the Worlds as a radio news broadcast...

Forgotten

Silver uses all the tricks of documentary –

old photographs, archive film footage, expert

and witness interviews, newspaper clippings, evidential

documentation, museum exhibits, a soberly delivered

and authoritative voice-over, vérité

footage of Jackson and his team in search of the Salome sets, and footage of the reconstructed film's

premiere – to mount a largely convincing portrait of

an extraordinary historical figure. But to anyone

with even a small knowledge of the development of cinema,

the clues are not so much scattered about as hurled

at you, and many of them are outrageous enough to provoke

outright laughter: McKenzie's traction-engine powered

camera; the newspaper headline 'Two Men Arrested: Smut Charges Brought'

after his first colour film test included shots of bare breasted native girls;

the Russian Cultural Attaché named Alexandra

Nevsky; the idea that McKenzie invented the tracking

shot because his first mechanical camera was powered

by and mounted on a bicycle, and that he did likewise with the close-up because he

was infatuated with the lead actress and just kept moving

the camera closer to her; the world's first example of candid camera through

MacKenzie's work with the terrible silent comedian Stan the

Man; and Leonard Maltin's

hilariously straight-faced suggestion that Stan's on-camera

police beating foreshadowed the Rodney King tape by

60 years; the utterly ludicrous digital enhancement

that reveals the date on a newspaper in a key piece

of archive footage.... the list goes on.

The

ideal way to come at any such work would be with no

foreknowledge of the trick that is being played on you,

but October 1995 has come and gone and the film has

become famous precisely because of its mockumentary

status. The principal pleasure of Forgotten

Silver thus comes from knowing exactly what Jackson

and Botes are doing and marveling at the skill with

which the fakery is executed, from the authentically

lit and faded archive photos to the recreation of a

variety of old film footage, complete with the sort of flicker

and damage you'd expect to find on film rescued from

decades of neglect and shabby storage. Every sincerely

delivered line, cheerily enthusiastic interview and

increasingly outrageous claim becomes irresistibly funny,

with even the more somber moments, such as McKenzie's

self-filmed demise, raising a knowing smile because of

the skill with which the particular cinematic style

is parodied.

Forgotten

Silver is a gem, a mockumentary executed with

real invention, considerable technical aplomb and a

mischievous sense of humour. Crucially, though it has

considerable fun with its subject, it never sets out

to mock it, openly celebrating both early cinema and

the enthusiasm and inventiveness of its pioneers. Most

of all, though, despite the very hard work involved

in its creation and the very small budget that the film-makers

were working with, Jackson and Botes are clearly having

the time of their lives, and irresistibly bring to mind

Orson Welles' claim that film-making is "the biggest

electric train set a boy ever had."

Although

apparently shot on 35mm, the picture here exhibits a

sometimes considerable amount of grain, but where elsewhere

this might be a source of complaint, here it genuinely

adds to experience, as it effectively distances the

film from the pin-sharp sheen of a Hollywood product

and looks very much the low budget, shot-on-the-fly

documentary it claims to be. Of course, this description

refers to the supposedly 'new' footage (interviews,

Jackson, Botes and their team in search of the Salome sets) – the rest consists of a combination of real and

fake archive footage and photographs, some of which

which have been deliberately aged and damaged. Given

all this, Anchor Bay have done a solid job on the transfer

– framed at 1.66:1 and anamorphically enhanced, the

contrast is strong, black levels very solid, and the

colour, though muted in places, is just right for the

material. A very slight flicker is visible occasionally,

but this may well have been deliberate. Given its minute

budget and deliberately low-rent feel, this is a good

as you'd expect the film to look.

The

Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack is often centre-weighted,

but many of the sound effects and some of the music

is spread effectively across the front speakers. The

clarity of the mix is admirable, and the base notes

of Plan 9's subtly parodic score are very sturdily reproduced.

The

are two absolutely essential extras included here that

make this disk worth buying for any fan of the film. The

first is the documentary Behind the Bull:

Forgotten Silver (21:52) which, despite

its brief running time is packed with information about

the making of the film. It features interviews with Jackson,

Botes and their collaborators, as well as public reaction

to the first screening and a priceless look at how some

of the faked footage looked before the ageing effects

were applied. Of particular note is the staging of Richard Pearce's

first flight, a combination of models and blue

screen work that would easily have been recognised as

such were it not for the battered condition of the final

footage. Equally eye-opening is the creation of the ruins of the Salome sets, which was achieved by piling trees and greenery onto the steps

of the National War Memorial, which is situated right next to a

main road. This is a terrific and tightly packed extra

that really gives a sense of both the work involved in

creating the film, and the fun that was had by those involved.

This extra is presented 4:3 but, somewhat mysteriously,

anamorphically encoded.

Secondly

there is a Feature Commentary by co-director Costa Botes. Despite intermittent (but

thankfully short) gaps, this is again fairly loaded with

detail. Even when pointing out the obvious, Botes'

deadpan delivery is entertaining, as with his description

of Jackson in the opening scene "leading people up

the garden path, quite literally," or when commenting

on the interviews with himself, Johnny Morris (playing

a film archivist), Harvey Weinstein and Leonard Maltin:

"Here I am telling lies. Johnny's telling more lies.

Now we get to someone semi-famous telling even bigger

lies. Now here's someone really famous, and when he tells

a lie people tend to sit up and listen." There is a

little duplication of some material from the documentary,

as in establishing the essential truth of much of the

Richard Pearce sequence, but for the most part this is

all fresh stuff, ranging from the factually interesting

– his discovery after the film was complete that the Australian

Salvation Army Film Unit had actually made a feature length

film in 1906, two years before their fake claim for Colin

McKenzie – and the amusingly anecdotal, as with his dismissal

of Jackson's suggestion that they interview up-and-coming

film-maker Quentin Tarantino for the documentary because

he just wasn't that well known.

Also

included are a selection of Deleted Scenes (8:52), which though not really adding to the story

in any major way (though the interviews detailing Colin's

dealings with the Chinese are interesting) are fun to

watch, especially the footage of the intrepid film crew

on location in the New Zealand bush, pondering on what

they may find – knowing what they were up to, just watching

them stumble through their improvisations (and in one

case try not to laugh) has its own pleasures.

Forgotten

Silver is probably Peter Jackson's least widely seen

film, which is a huge shame as, along with his first feature Bad Taste, it is the one that most obviously

reflects the director's love affair with cinema and the

joy he takes in the process of its construction. This

is film-making for the sheer fun of it, and Jackson and

Botes are masters at conveying that to an audience, at

least one that is in on the joke. And lest we, as film

enthusiasts who can spot the absurdities at a thousand

paces, mock those who were taken in by the film on its

first screening, I have an anecdote of my own. Last year,

I taught a class in documentary film for 16-20 year-olds

who were relatively new to the codes and conventions of

the genre, and after several weeks of screening key documentary

works and prompting them to shoot and edit some footage

of their own, I screened Forgotten Silver for them.

I revealed little about the film in advance, just that

it told an extraordinary tale and was co-directed by the

by now internationally renowned Peter Jackson, the idea

being to ask each one of them afterwards at what point

they had twigged they were watching a carefully constructed

lie. None of them did, and they were genuinely gobsmacked when

I told them the truth. I like to think that in spite of

the considerable pleasures to be had from the film when

you know it's all a fake, Botes and Jackson would draw

some pleasure from knowing that their deliciously well-executed

jape, given the right audience and set-up, is still capable

of being taken at its word.

|