I hurt myself today

to see if I still feel

I focus on the pain

the only thing that's real. |

| Hurt – Nine Inch Nails |

Have you ever hurt yourself, just to see what it felt like? How about cut yourself? No? Of course not. That's famously something people who hate themselves do, a form of self-punishment that leaves a physical reminder of the inner pain that prompted the act in the first place. Or at least that's we are told. I can tell you from personal experience that it's not that simple – people harm themselves for a variety of reasons and not all of them can be written off as symptoms of mental anguish. Many of you reading this may have at least dabbled with the concept without even realising. Ever picked a scab or pressed on a bruise? Why would you do that if it causes pain or slows the healing process? And have you ever lost a filling or broken a tooth and had to wait for an appointment to get it fixed? Think back, did you just try your best to ignore it, or did you repeatedly prod it with your tongue or a finger? Did it hurt? Even if it did, I'll bet good money that you prodded it again. And again. And what about that niggling hangnail that kept catching on clothing? Did you carefully remove it with nail clippers, or did you bite it off? I'll bet it felt good when you finally got it. If none of this means anything to you then you are probably going to have some major problems with writer-director Marina de Van's debut feature, In My Skin [Dans ma peau], and even if it does, you may well find yourself out of your depth.

The potentially destructive nature of the pursuit of bodily gratification was most famously and bewitchingly explored by David Cronenberg in his mesmerising adaptation of J.G. Ballard's Crash, whose protagonists achieved sexual fulfilment by exposing themselves to the possibility of violent death and disfigurement by crashing their cars. The film was dogged by controversy on its release and prompted howls of outrage from the right wing press, which completely failed to understand (or simply refused to deal with) the subtextual thrust of the piece. But where Crash was a communal affair, the journey taken in Dans ma peau is very much a solitary one.

The story revolves around Esther, an upwardly mobile professional woman in a stable and loving relationship that nonetheless takes second place to her career. Attending a party one evening, she wanders into the garden and takes a fall, injuring her leg to a degree that necessitates medical attention. Even at this early stage, de Van throws a curve ball when Esther dismisses the fall as a minor incident and only realises just how badly she has been hurt a while later when she spots the trail of blood that she is leaving. Her initial reaction is one of horrified disbelief – a natural one to such a bad gash – but her surprise raises a question re-enforced by the doctor (played by the director's brother Adrian de Van) who eventually treats her wound. The injury should have caused her considerable pain, but until the discovery of the blood trail she had remained blissfully unaware of the damage done to her leg. So after discovering the injury, she heads straight to hospital, right? Well, no. Instead she hides the wound and suggests to her companions that they head to a bar for one last drink. Only afterwards does she seek medical advice.

It's at the hospital that the first real pointers become evident, with Esther's reaction to the treatment an unusual mix of curiosity and mild arousal, and from this point on she develops an increasing fascination with the wound. When it starts to distract her from her work, she sneaks into an empty filing storage room uses a metal door hinge she finds in a toolbox to physically attack it. She then takes things a step further by inflicting a new wound with a physicality that suggests that this is no mere scratch, something emphasised by a wince-inducing sound effect and a perfectly timed edit (or, more appropriately, cut).

This will likely prove a turning point for much of the audience, the moment when they will either go with de Van or tune out completely. The majority of those I spoke to after our cinema screening back in 2005 were willing (albeit squeamishly) to follow where de Van was leading them, and I'm guessing this had less to do with their own history of self-harm than the metaphoric level on which the film was by then clearly operating. Esther's discovery is one that she finds compelling but remains secretive about. The whole filing room incident, despite the violence of her action, has masturbatory overtones that all but the most prudish (who, let's face it, would not even think about watching such a film) should instantly recognise and possibly even directly relate to. Thus, when Esther confesses to her friend and colleague Sandrine (Lea Drucker) what she has done with the aim of sharing her discovery with someone who may at least sympathise, Sandrine's uncomfortable response prompts her to do an immediate about-face.

It's here that Esther realises that her new fascination is something that she needs to keep to herself and that others would negatively judge her by. Later, at a poolside social gathering, a group of male colleagues playfully attempt to disrobe her to throw her into the water, and her reaction is one of screaming panic, as they come perilously close to exposing her dark secret. Her frantic, desperate pleas for help fail to move Sandrine, whose initial concern and later alarm at the physical result of her friend's action have just been further coloured by her jealousy at the news that Esther has just landed the sort of managerial position that Sandrine has been seeking for some years. From this point on their friendship is effectively over. More direct in his response is Esther's boyfriend Vincent (Laurent Lucas), who reacts angrily on learning that her wounds are self-inflicted, in much the way he might if he discovered that she had been secretly using a class-A drug. It's a reaction born from a genuine concern for her wellbeing, from his fear at the harm she is doing to her body and where it might ultimately lead.

The obsessive, damaging relationship metaphor is at its most devastating in the film's supremely uncomfortable and uncompromising centrepiece. Required to attend a business dinner with her new boss Daniel (Thibault de Montalembert) and two important clients (Dominique Reymond and Bernard Alane), the teetotal Esther is persuaded to take a drink and then starts to completely lose control of her obsession. Disorientated by her surroundings and the chatter of her fellow diners, she hallucinates her left forearm as a lifeless object detached from her body and lying on the table before her like a rolled-up napkin. After quietly retrieving and reattaching it, she pinches its skin and brutally stabs at it with a steak knife while a state of increasingly agitated fear and confusion that she tries her best to hide but that does not go unnoticed by her companions. When the dinner concludes, she checks into a nearby hotel for what is essentially an urgently driven and fiercely passionate sexual liaison, not with another man or woman but with her own flesh, an encounter gruesomely realised with her teeth and a stolen dinner knife. There is no musical accompaniment to this sequence, no attempt to impose a surrealistic tone, with the moans and cries of sex replaced by the sounds of biting, chewing and cutting, as Esther attacks her own body, blood drips onto her face, and self-harm edges into the realm of cannibalism. It is a scene of quite extraordinary intimacy and deeply disturbing reality, and one that proved too much for a good part of the audience at our cinema screening, who turned their heads away and mumbled into their handkerchiefs. Or so I was told. I, you see, could not take my eyes off the screen for a second. Only afterwards did I question what that said about my own reading of what had just occurred.

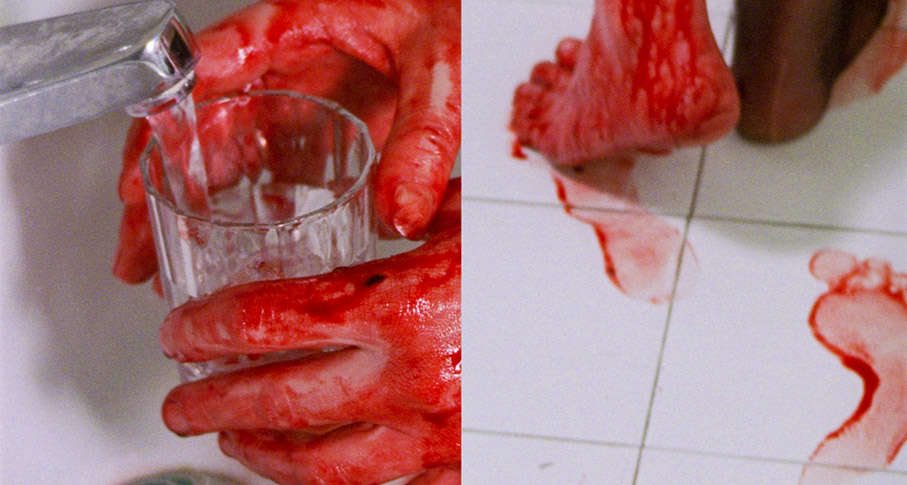

Even at this stage, Esther remains concerned about how Vincent will react, and to that end stages a car crash in the vain hope that he will believe that the injuries were caused by the accident. It counts for little, as from this point on she is trapped in a spiral of self-destruction, a violent love affair with her own flesh that only she cannot see is destroying her. By the time we reach the finale, which de Van presents as a split-screen montage of grimly suggestive and ultimately blood-soaked close-ups and almost ghostly looks into the camera, you can pretty much select your own metaphor – abusive relationships, sadomasochism, the deadening effect of the corporate world, incest, drug addiction... There are plenty more to choose from and all of them work, because despite what many will regard as the dissociative nature of Esther's obsession, there are too many familiar touchstones along the way for us as viewers to remain at arm's length. We may not understand exactly why she does what she does, but to a certain degree many of us have been there too or know someone who has, whether it be a destructive or unhealthy relationship that only we were unable to see the harm in, or a dependence on drugs, alcohol or even cigarettes that feels fine while indulging in but is slowly tearing away at the body inside. When Esther cuts a square of skin off of her leg and attempts to preserve it, the relationship analogy is impossible to ignore – not properly cared for, it withers and dies, becoming a treasured memento to be mournfully pressed against her breast like the body of a deceased child. It is no doubt these subtextual readings that prompted a female friend after our cinema screening to say to me: "What she was doing was really horrible, but in a funny sort of way, I knew where she was coming from. Does that make sense?" To me it did. Perfectly.

De Van's real trump card is in casting herself in the lead as Esther. This is no cost-cutting compromise but a bold and very deliberate decision that effectively eliminates any potential barrier between directorial vision and performer interpretation, as well as quashing any worrying doubts about what the director put her lead actor through. De Van is a compelling screen presence, and it's her confidence and unwavering commitment to the role that sells Esther as real. If the film itself is a million miles from a Hollywood product, then de Van's performance is likewise divorced from its mainstream counterpart. There is no ego at work here, no manufactured image to project, no self-censorship and seemingly no fear. Whether trailing a camera over her own naked and injured body in the shower or exploring the elasticity of her skin while sitting in the bathtub, de Van's matter of fact and sometimes unflattering presentation of her own flesh is at the same time both startling and yet crucial to why the film is so damned effective, as is the almost brutal physicality that she brings to key scenes. This is most clearly evident in the sequences of self-mutilation, which she throws herself into with a such conviction that it never for a second feels like a performance – indeed, there are times (particularly the hotel scene) when the audience is very much put in the position of a voyeur, which makes the scenes themselves all the more troubling to watch. Equally effective are the smaller, low-key elements of de Van's portrayal, her moments of realisation, confusion, fear and spaced-out delirium, all of which are communicated so believably that the line between acting and experience all but dissolves.

In My Skin is confrontational cinema in all that is positive in that term. On the surface, it's a body-horror story about the exploration and destruction of flesh and a discovery of emotional feeling through physical pain. Yet if viewed on a metaphorical level, as it inevitably must be, this is one of the most charged and confrontational films of 2000s to date. Twenty-one years after it first arrived in UK cinemas it's lost none of its impact or relevance, and returning to it after a break of many years I found myself once again pulled completely into de Van's world. Perhaps due to my age and my own now distant experiments with self-harm, this time around her story touched and moved me in ways I wasn't expecting, though this is partly down to what I learned from the interview with de Van on this very disc. Here, she reveals a crucial fact that I was previously unaware of, that the scenes in which Esther bites and cuts her body and chews on her own flesh were recreations of acts of self-harm that de Van had previously inflicted on herself for real. For me, this added a whole new layer to her decision to play the role and is a key reason she was able to depict these difficult scenes with such conviction – she wasn't just performing these acts, she was re-living them.

The film is often cited as being part of the New French Extremity wave, but this is a classification that de Van herself rejects. Frankly, I'm in her corner on this one, as extreme though some of the content may be, the film is not designed specifically to shock and confront its audience and is told from a very personal perspective. It is, as de Van says in her interview, an attempt to confront her own issues on film and (successfully, as it turns out) finally exorcise them and free herself from them. Although she has continued to direct works of real interest, in this one extraordinary piece of writing, directing and acting, de Van takes us to even darker, more intimate and personal places than the rightly celebrated Crash dared. As former site reviewer Lord Summerisle remarked to me as we left the cinema after that first screening, "Cronenberg must be really jealous."

This UHD/Blu-ray edition of In My Skin has – for me, at least – been a long time coming, as the film was previously only available on disc in the UK as a DVD put out by Tartan Video back in 2005 under its original French title of Dans ma peau. When Tartan went into administration three years later, even getting hold of that disc became a task and a half, so all hail Radiance for this most welcome upgrade. The Limited Edition package features a new 4K presentation of the film that was produced by Severin Films in association with Cité de Mémoire/LTC Patrimoine and is presented in 4K on UHD and in HD on Blu-ray.

The restoration process itself was a little unusual. To quote the caption that precedes the film:

Although the film was shot on 35mm celluloid in 2002, the dailies were transferred to tape and the movie completed in HD. In order to remaster the film for UHD in 2025, Cité de Mémoire/LTC Patrimoine scanned the individual takes that were used in the movie in 4K and reassembled the cut digitally.

The assembly was then delivered to Severin Films for colour correction and restoration. The final 4K master was approved by director of photography Pierre Barougier.

That last sentence is especially important, as it confirms that the 4K transfer here is has been confirmed by the cinematographer as being how the film is supposed to look.

So how does it look? Well, let's get the obvious out of the way and state that both the new Blu-ray and UHD transfers included in this release represent a substantial leap over the anamorphic SD transfer on the Tartan DVD. Detail is far crisper, the colours more distinct, and the contrast better graded, plus, of course, the film now plays at its correct frame rate of 24fps instead of the 25fps that was the PAL DVD standard. When it comes to the differences between the new Blu-ray and UHD transfers, it's not quite so clear cut, and I'd argue that's down in part both to the film's chosen aesthetic and the strength of the Blu-ray transfer. On wider shots, there's very slight softness to the image that results in it have an almost identical look on both formats, although the Dolby Vision HDR brings out slightly more detail on the UHD. Where the UHD really shines is on the close-up shots, of which there are many, where the detail is really sharp, brighter colours (such as the blue of Esther's blue bathrobe or the deep red of the blood in the finale) really pop, and the contrast grading is top notch. A word of warning, however, as this does mean that the close-up shots of wounds and Esther's slow removal of the blood-stuck hospital bandage are all the more wince-inducing, so convincing is Dominique Colladant's remarkable special makeup work. The HDR really helps in the more darkly lit shots in the finale, improving the shadow detail without having to inappropriately brighten the picture, and the warm tones of the artificially lit interior scenes that I remember from our cinema screening remain, while the daylight exterior shots have a pleasingly naturalistic look. As you might expect, the image is clean and is consistently stable in frame, and a fine film grain is visible without being intrusive.

The soundtrack is presented in DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround on both discs, and for much of the film it's a distinctly front and centre mono affair, which is appropriate for scenes in which dialogue is delivered, or sounds are made by characters in otherwise quiet rooms. In busier locations such as restaurants, supermarkets and street exteriors, the ambient sound widens and becomes more inclusive, and Esbjörn Svensson's sparsely used score makes full use of the 5.1 sound stage. The mix is very clear and boasts a strong but never distractingly attention-grabbing tonal range.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default but can be switched off if your French is up to the job. The Blu-ray disc is coded region B, but the UHD is region free, and the film is framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The majority of the special features here are new to this release, with only the commentary track and the trailer ported over from the earlier Tartan DVD release. While the commentary is included on both the UHD and the Blu-ray discs, all of the other special features are on the Blu-ray disc only.

Audio Commentary by Marina de Van

Conducted in French with optional English subtitles, this 2005 commentary track by writer-director-lead actor Marina de Van is certainly a busy one, with de Van barely pausing for breath throughout. She talks a lot about the central character and her motivation, and deconstructs the thinking behind some scenes, all of which is of considerable interest. Perhaps inevitably, given her very personal attachment to Esther, there's little discussion of the technical or even artistic aspects of the filming. What does surprise in retrospect is the fact that the self-harm was based on de Van's own experience gets no mention. I'm guessing it took the passing of time for her to open up about this aspect of the film.

Marina de Van (26:20)

A newly filmed interview with writer, director and lead actor Marina de Van, who is open from the off about the film's autobiographical element, revealing that while the scenes of self-harm were faked for the film, they are accurate recreations of her own experience with self-inflicted bodily injury, the details of which will likely widen a few eyes. One of the reasons she gives for making this her first film was that she hoped it would provoke her to stop self-harming, which it did, though not for the expected reason. She reveals that the film was made out of hate (this claim is explained), and that she cast herself in the lead role because she believed that another actress would have a judgemental view of the character and would fail to understand her thinking and motivation. In preparation, she spent a year working with acting coach Marc Adjadj, who was also on set to effectively direct her and the other actors while she focussed on her performance, a task that her brother Adrian took over when Adjadj was unavailable. She cites the business dinner scene as her favourite, rejects the idea that the film is part of the New French Extremity movement, is critical of Claire Denis' controversial 2001 erotic horror feature Trouble Every Day (which she describes as "inappropriate"), but does admit liking the confrontational films of Gasper Noé. While she is pleased that In My Skin is still being discussed so long after it was made, she's disappointed that no-one ever asks her about her subsequent features. The interview is conducted in French with optional English subtitles.

Pierre Barougier (21:52)

An interview with the film's director of photography, Pierre Barougier, whose recollections of first meeting de Van and being introduced to material to help him get into the world of the central character, are peppered with interesting details. He reveals that he and de Van spent weeks pre-shooting the film with a video camera, which enabled them to plan the film's visuals in advance, freeing de Van to focus on her performance during the shoot itself. This put a great deal of responsibility on Barougier when filming began, and he admits that de Van became so involved in her character during the supermarket sequence that he momentarily lost her as a director. He explains the thinking behind the use of split screen during the opening titles and the gruesome finale and admits that he now finds the film a tough watch in places, suggesting it inspires an attraction-repulsion feeling in the viewer. "My wife never saw it," he reveals, "and she doesn't want to see it."

Marc Adjadj (20:16)

An audio interview with renowned acting coach Marc Adjadj, with whom de Van worked closely to develop her character and brought on set to help direct her and her fellow actors. He's full of praise for de Van's intelligence and commitment, and outlines how they first met, how he became involved in the preparation for In My Skin, as well as how he worked with her during the filming. He notes that for the first three days of shooting, the cast and crew were wondering who he was and wanted to kick him out, describes how he collaborated with de Van on specific scenes, and salutes the contribution to the film and de Van's performance made by editor Mike Fromentin and special effects makeup artist Dominique Colladant.

Student Shorts

Two short films made by Marina de Van while at the La Fémis film and television school have been included here.

Bien sous tous rapports (11:53)

Made in 1996, this was Marina de Van's first short film for La Fémis, and it wastes no time in establishing her willingness to confidently walk where few filmmakers feel remotely comfortable treading. A girl enters her family home with a boy that we quickly realise she has only recently met, and after introducing him to her parents and her two brothers, she takes upstairs him to her room. Here she quickly overcomes his shyness and starts to fellate him, only to have the family burst in and demand that she stop, something she is clearly unwilling to do. The boy reacts with startled disbelief to this intrusion and is promptly sent on his way, and the family then gathers downstairs to watch and a secretly filmed video of the encounter as the parents berate their daughter for her poor technique and posture. And if you think this tests the limits of taboo, just wait until you see where the story goes next, and I've not even mentioned that the video the family watch of the daughter fellating her pickup appears to be unsimulated. Interpretations will vary, but for me Bien sous tous rapports – which I believe translates as Good in All Respects, a surprisingly appropriate title – plays as critique of extreme parental control and attempts by adults to shape the behaviour and personalities of their offspring, a theme that was later examined in equally provocative fashion in Yorgos Lanthimos's 2009 Dogtooth [Kynodontas].

Rétention (15:10)

In her second film for La Fémis, de Van lays some of the groundwork for her debut feature by also taking the lead role and having no qualms about what she was prepared to show and do in the role. Here she plays a troubled woman living alone in a squalid apartment in which she is tormented by the sound of other, possibly imagined occupants of the building, of whom she appears to be terrified. When they start banging loudly on her door and trying to force their way in, she breaks out through a window and flees into the street, where she suffers a complete mental and physical breakdown. A straightforward enough premise, perhaps, but executed in a manner so mind-bogglingly troubling that I can't be sure that my description is even remotely accurate to de Van's intentions. Her refusal to self-censor is as evident in her unabashed presentation of her own body as it is in the content of the film, as she sits on a toilet and brings herself to violent (and possibly defecation-triggered) orgasm by shuffling rosary beads in her right hand, and later tears at her flesh to the point where she seems to be pulling her internal organs apart. Given her frank admission in the interview on this disc, I did find myself wondering if the self-harm scars visible on her legs were the real deal.

Manuela Lazic (12:05)

This interview with writer Manuela Lazic is one of those special features that pops up every now and again where the interviewee makes some of the exact same observations about the film as I have in my review, making it look almost as if I simply transcribed her words. In my stout defence this time around, I should point out that the above review has been updated from my now 21 year-old coverage of the 2005 Tartan DVD release of the film, including the comments that Lazic eloquently makes here. It's certainly nice to know that I'm not the only one who read Esther's obsession as a passionate relationship with her own skin. Lazic also makes a good point about the compassion that the film shows for Esther, and that despite – or more likely because of – the autobiographical aspect, de Van shows that Esther's obsession is ultimately a dangerous dead end.

Bleed Like Me: Eroticism, Flesh and Violence in the Films of Marina de Van (10:39)

A visual essay by Morena de Fuego (aka Valeria Villegas Lindvall) and Eme Erre (aka Mauricio Rodríguez) – who credit themselves here as Morena de Fuego X Eme Erre – on de Van's early work up to and including In My Skin, one that leans into an intellectual reading that I suspect will intrigue as many as it leaves cold. There are some interesting points made here, notably the observation that de Van's cinema is one of transgression, and that her films are as visceral as they are intellectual, and I did like the suggestion that her work is "an unbearable cinema of the senses."

Trailer (1:37)

A straightforward but effective enough trailer that gives a flavour of what Esther is doing to herself and the reaction this new obsession has on others without showing anything too graphic.

Also included is a Limited Edition Booklet featuring new writing by critic Savina Petkova and archival writing by Marina de Van, but this was not available for review.

Even with the hindsight of passing years, it's clear that In My Skin was never going to find a large audience, something reflected in our film society screening, which attracted the smallest attendance of that season, with many of our regulars revealing that they felt unable to deal with this subject matter, let alone its realistic handling. But for me, the film remains great outsider cinema in every respect – daring, provocative, utterly committed to its vision, a very personal project that disturbs with real purpose, warning of the danger of self-destructive obsession whilst allowing us to sympathise and even empathise with the addict. If you are seriously squeamish then you are still probably going to have a problem with the film, but if you're prepared to go where the multi-talented de Van wants to take you, then I can promise that this is a journey you will not forget in a hurry.

Radiance has done the film proud with this superb new Limited Edition UHD/Blu-ray release, which features a top-notch 4K restoration and transfer, and a terrific collection of special features, including two of de Van's student shorts. Not an easy watch, but if you're game, a rewarding one, and this release gets our very highest recommendation. |