|

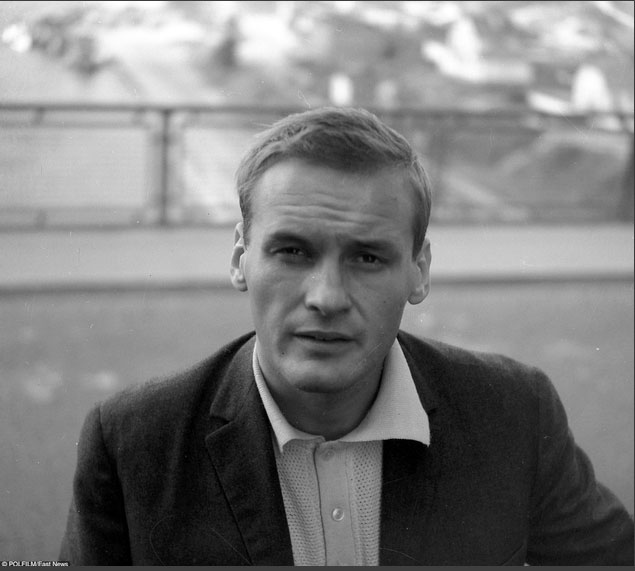

In 1960, Jerzy Skolimowski collaborated with Andrzej Wajda on Innocent Sorcerers, in 1962 with his pal Roman Polańkski on Knife in the Water. His 1967 film Hands-Up was banned for 18 years in his native Poland, from which he was also exiled by the Stalinist regime. The New York Times paired Moonlighting, his 1980 satire about the banned Solidarity movement, with Polańkski’s The Tenant as ‘the two best films ever made about exile.’ In 1984, he lost his house after the failure of Success is the Best Revenge. Following the failure of Ferdydurke, his 1991 adaptation of Witold Gombrowicz’s subversive novel about the effects of an infantilising culture, he left cinema behind for 17 years. In 2016, he received a Golden Lion Lifetime Achievement Award at Venice. Last year, he won his first Cannes Jury Prize and first New York Film Critics Award. He may not have seen it all, but he’s seen plenty. Now an exhibiting painter, he began as a published poet and unsuccessful welterweight boxer. In Prague, he went to school with Milos Foreman, Ivan Passer and Vaclav Havel. In London, he lived in the same building as Jimmy Hendrix. He has acted in films as various as David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises and Marvel’s The Avengers. As Cervantes said, ‘El que lee mucho y anda mucho, ve mucho y sabe mucho/He who reads a lot and travels a lot, sees a lot and knows a lot.’

Skolimowski’s stunning, critically acclaimed eighteenth feature, EO, represents a distillation and synthesis of all he’s learnt of cinema and life in decades of movement and risk, and in a career of breath-taking audacity, invention and originality. Thanks partly to the success of EO, London audiences will soon have a chance to view that extraordinary career in the round during a long-overdue BFI Southbank retrospective: Outsiders and Exiles: The Films of Jerzy Skolimowsk [27 March-30 April], organised by the BFI in conjunction with Kinoteka's 21st Polish Film Festival. As if that prospect were not mouth-watering enough, Kinoteka’s feast of a festival also contains a strand on Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk’s magnificent novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. Tokarczuk’s ecological satire sits alongside Václav Marhoul’s adaptation of Jerzy Kosiński’s The Painted Bird as two works closest in tone and temprement to Skolimowski’s EO. Both arose from the same fertile soil of Mitteleuropa from which EO springs and are equally infused, with the mournful melancholia of peoples all too familiar with the human capacity for cruelty. Like EO, Tokarczuk's novel (an eco-feminist-animal-rights-noir-thriller like no other. Is there another?!) fiercely argues for peaceful co-existence with all creatures with whom we share our despoiled planet. Like EO, Marhoul’s film charts an innocent’s odyssey across Central Europe while reminding us that the contending human capacities for cruelty and decency are universal and timeless. Such influences, echoes if not touchstones, merely hint at Skolimowski’s depth, range and reach.

With EO, Skolimowski adds Isabel Huppert to the steady stream of heavyweight actors he’s worked with down the years (Alan Bates, Claudia Cardinale, Robert Duval, Vincent Gallo, Gina Lollobrigida, John Hurt, Jeremy Irons, Nastassja Kinski, Jean-Pierre Léaud, David Niven, Michael York, Susannah York, Elli Wallace, etc). Huppert, who has seamlessly replaced Jeanne Moreau as the ice maiden of French film, performs her box office function with a spiky aplomb as an Italian heiress. Not even Huppert, though, can have presented Skolimowski with greater nervous challenges than those presented by the notoriously stubborn protagonist of EO, a light-grey-furred, ring-and-liquid-eyed donkey, or, to be precise, the six Sardinian equids who comprise the fictional whole. Being simply and naturally themselves, animals do not and cannot act. Being often simple creatures also, many actors can only play themselves. That said, the erratic behaviour and individual characteristics of animals can cause problems all of their own. Few actors, as far as I’m aware, excrete or urinate on set. Fortunately, Skolimowski says, carrots can work miracles.

Au Hazard Balthazar

Mere mention of donkeys inevitably calls forth thoughts of Robert Bresson’s revered masterpiece Au Hazard Balthazar, which Jean-Luc Godard famously described as ‘the world in an hour and a half’ and which was recently ranked 25th in Sight & Sound’s ludicrous ‘Greatest Films of All Time’ poll. Skolimowski saw it upon its release in 1966, after it pipped his own Walkabout to Cahiers du Cinéma’s Film of the Year accolade. It is the only time he has ever wept in a cinema, he says, never before, never since. EO takes its lead from Bresson’s morally pessimistic tale of human cruelty, but Skolimowski’s equally effecting film stubbornly refuses to be shackled to mere imitation.

There are clear parallels between the two films; most obviously, both contain vulnerable female leads and viscous male antagonists, feature donkeys passed from hand to hand, and insist that those beautiful beasts of burden deserve our pity and respect. Inevitably, they also share similar detailing: the beatings, braying, carts, carrots, circuses, hay, hooves and so forth. The two films could not be more different stylistically though, nor could the contrast between Bresson’s rigorous asceticism and Skolimowski’s vigorous flamboyance be more marked. Bresson’s film is rooted in place and punctuated with silence whereas EO is a clamorous road movie restlessly on the move, Bresson’s minimalist parable is shot in limpid black and white while Skolimowski’s expressionist fantasia splashes colour across the screen with abandon, Bresson’s realist narrative traces a conventional chronological arc where EO proceeds in a serrated series of picaresque vignettes. Susan Sontag argued that Bresson’s distinctive form was ‘designed to discipline the emotions at the same time that it arouses them: to induce a certain tranquillity in the spectator.’ Skolimowski’s is designed to destabilise our emotions: to induce in us a profound sense of unease.

As the opening credits roll in Au Hazard Balthazar, the elegantly elegiac cadences of Schubert’s Sonata No. 2 soothe us before we’re disturbed by the unmelodious scene-setting bray of a donkey. EO opens with a blaze of crimson, a booming surge of sound, and a disorientating scene that initially appears part violent struggle, part sexual encounter but finally reveals itself to be a play-dead circus act. Eo’s trainer Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska) appears to love him, and he seems to return her feelings. On this level, EO reads as a heartrending love story and forsaken Eo’s odyssey as one long journey toward reunion with her. The flashback sequences in which Eo seems to be mournfully recalling her are among a number of discordant anthropomorphic notes that nonetheless emphasize the theme of loneliness. More generally, the film respects the rights and inscrutable interiority of animals. More generally, as Manohla Dargis neatly put it in the New York Times, ‘Skolimowski reminds you that Eo is an animal, not a prop or a plushie, a comic contrivance or a child substitute.’

Aptly, Eo is liberated from the circus by animal rights activists as it is declared bankrupt, and, after the first of his several trips in box trailers, arrives at a state-sponsored equestrian centre. Here, he gazes upon a frisky Arab stallion being put through its elegant paces in the training ring. The horse repeatedly kicks at its stable door, perhaps in a bid to escape, perhaps to reach a nearby mare. As with so much that happens in the film, we are left to draw own conclusions and invited to impose our own thoughts on the donkey. Startled by the horse’s agitation, Eo comically tips over a trophy cabinet and is consequently sent to a donkey sanctuary. Here, he pines for Kasandra, too depressed to eat the carrots offered to him, and here his innocence meets its match - in the kids with learning difficulties he gives rides to. Kasandra tracks him down to the sanctuary and feeds him his favourite carrot muffin. When she reluctantly departs on her partner’s motorbike, Eo sets off in pursuit. He finds himself deep in a darkling forest reminiscent of the one in Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead, at the mercy of hunters like the ones killed one by one therein. The hunters’ fluorescent lazer beams come to rest on Eo’s hide. We fear for him, but he escapes unscathed, leaving a dead fox behind on the forest floor. As he views the poor creature's corpse and as he tiptoes through an overgrown Holocaust graveyard, we wonder again what Eo must be thinking. We can but suppose he'd conclude, as we must, that the whole wide human world has gone stark staring mad.

After a brief interlude of freedom in the woods, on a hilltop at dawn, and in an eerie tunnel that seems to stretch for miles, Eo is again re-captured – lassoed by council workers in a small town as he stands braying at tropical fish trapped in a tank. Skolimowski forces us to think about freedom and imprisonment throughout. Eo is rescued again, by a kind-hearted Anarchist with whom he watches a roughhouse local football match. He is adopted as a lucky mascot by the home team’s triumphant supporters, but their club house is viciously attacked by brutish away fans – who subsequently beat Eo to within an inch of his life. Moved to an animal hospital, he is nursed back to life by a veterinarian faithful to the Hippocratic oath. Eo next finds himself in a fur farm, where he exacts revenge on behalf of the emaciated mink and foxes being held in cages and slaughtered there - by kicking their killer and tormentor in the head.

Revenge is another recurring theme in EO, as it is in Tokarczuk's above-mentioned masterpiece. It occurs again after Eo is added to a consignment of horses due to be transported to the slaughterhouse, there to become salami. The transporting lorry driver, having lured a desperate female migrant into his cab with offers of food, also meets a sticky end. Rescued once again, this time by a loose aristocratic drop-out or defrocked priest (Lorenzo Zurzolo), Eo travels home with him to the palatial villa recently sold off by his voluptuary stepmother (Huppert). Again, we’re left to imagine what might’ve occurred between the two before he left home. We’re left in little doubt, though, where the sizzling sexual charge between them might lead. Abandoned once again by one who seemed to love him, Eo wanders forth, finally, at the film’s close to mingle with a herd of cows and meet his final destiny.

As that brief plot synopsis should suggest, Skolimowski keeps us guessing throughout the film - shuffling scenes like a cinematic card sharp, always keeping aces up his sleeve, playing wild cards at will. His jagged narrative seldom lets us settle. Godard said that while Bresson’s other films were ‘straight lines’ Au Hazard Balthazar (starring his second wife Anne Wiazemsky) was composed of ‘concentric circles, overlapping one another.’ EO is full of concentric circles too, and sharp edges. Aside from Polańkski, Godard is the director to whom Skolimowski is most often compared, but the comparison hinges exclusively on their energetically inventive improvised films of the sixties. Just as Godard did, Skolimowski values spontaneity. He constructs his film from whatever is to hand and springs to mind. Startlingly, a robotic dog lurches into the film at one point. Why?, we wonder. Why not?, he’d presumably reply. Skolimowski holds fast to two commandments: 'Not to be boring. To be aesthetic.' EO is never boring, occasionally jarring, often dazzlingly beautiful, always riveting. It is infinitely more pacy, rapidly edited and surreal than Bresson’s muted work, more Godardian we might say, and more explicitly political in its implicit demands for animal rights

EO contains overlapping concentric circles and no end of dead ends, detours, digressions, twists, turns, and a few false starts too. All of which is consistent with Skolimowski's boredom with conventional narrative and commitment to bold experimentation. If he makes another film, he says, he's determined to break conclusively with what Peter Wollen called 'narrative transitivity' – 'a sequence of events in which each unit (each function which changes the course of the narrative) follows the one preceding it according to a chain of causation.' ' With EO he has already taken his first steps toward the anti-narrative impulses of counter-cinema and the avant-garde. Ten years ago, in reflex reaction to the technical virtuosity of Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel's documentary of sailors at sea, Leviathan, I made an overwrought, overstated case for it as, paradoxically, both proof proper of cinema's second coming and harbinger of a new digital dawn. Despite André Bazin’s preference for fiction and insistence on the indexicality of photography, that film seemed to me, then, to validate his claim that cinema’s cardinal virtue lies in its capacity to represent reality (or, as, we might now say, the reality of representations of reality at least). Leviathan seemed to make manifest Dziga Vertov’s assertion that the camera-eye is more perfect than the human eye.

I’m half tempted to say the same of EO, such is its equally impressive use of the full range of cinema’s accumulated techniques and tools: close-ups, colour saturation, dissolves, drone shots, dutch angles, fades, fish-eye lenses, flash photography, reverse motion, slow motion, strobe lights, tinting, tracking shots, zooms – film’s full kit and kaboodle. Above all, the constant close-ups. Bazin regarded the close-ups in Carl Dreyer’s Joan of Arc as ‘a documentary of faces.’ To which idea, Roger Leenhard impatiently replied, ‘Ah, the sacrosanct close-up . . . the means of psychologically delving into a character, of going into the soul with a camera’ Wrong, he argued, ‘An exaggerated close-up of a face is not psychological and complex but lyrical and elementary.’ And nowhere more lyrical and elementary than in EO. Without the anchor of close-ups, of Eo's face and eyes, the film would tug free of its moorings, lose its bearings, and bob haplessly and helplessly on a heaving sea of engulfing images. As Jean Epstein said in 1921: ‘No painting. The danger of tableaux vivants in contrasting black and white . . . Impressionistic corpses. No texts. The true film does without.’ So, just photogénie, pure cinema. ‘The hills harden like muscles. The universe is on edge. The philosopher’s light. The atmosphere is heavy with love. I am looking.’

Now, nothing succeeds like excess. Cinema continues to extend its limits while drawing on all that’s been tried and tested in its history. Films beget films and there are many scenes in EO that send us back through cinema’s history. When Eo clatters across a deserted town square, Bela Tarr’s Satantango springs immediately to mind, as Eo peeps through the grills of his trailer at wild horses running free, Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames gallops into view, a waving meadow of wheat recalls Lynne Ramsey’s Ratcatcher, a moonlit river sends us back to Charles Lawton’s Night of the Hunter, and so forth. EO also sends us back, on a loop, almost to film’s first steady steps, to Soviet Montage Theory and the stance on the importance of editing that Vertov shared with Serge Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Esfir Shub. Eisenstein called montage ‘the nerve of cinema’. Paul Rotha called editing ‘the intrinsic essence of filmic creation’. The two terms are no more congruent than Eisenstein’s emphasis on the collision of images is with Pudovkin’s on their continuity, but, semantics aside, those Soviet pioneers agreed, as they developed the vocabulary of film language step by step, that montage to be the very beating heart of film.

Skolimowski’s cinematographer Michal Dymek and composer Paweł Mykietyn have deservedly garnered plaudits, but his Film Editor Agniezka Glinska deserves huge praise for her work. EO takes Eisenstein’s ‘montage of attractions’ to new heights, and it came as no surprise to hear Skolimowski consistently cite the ‘Kuleshov Effect’ to illustrate the core principle of montage. Take a man’s blank, expressionless face. Cut that image with one showing a bowl of fruit and the spectator will read hunger there; with a woman in a coffin, grief; with a woman in a state of undress, desire. Skolimowski edits and intercuts images of the donkeys in EO to similar effect: Eo’s equally inscrutable face becomes a canvas onto which audiences paint their own perceptions and prejudices, even as Skolimowski dabs on layers of his own. Faced with a blank face, we are obliged to supply emotions and thoughts of our own, which is why nobody can watch EO with a blank mind or hardened heart.

If EO can consequently be cartoonish at times, we’re sent back through film history again, to the streetwise buck-toothed wabbit with a Brooklyn accent who first sank his teeth into a carrot in 1940, paused, faced his sworn enemy, the shot-gun totting Elmer Fudd, and uttered three of the cheekiest, most defiant words in the whole of film history. In a piece on cartoon culture titled ‘What’s Up Doc?’, Jonathan Rosenbaum considered the principle of comic dynamics underpinning much of the violence in Hollywood cartoons: ‘the formal function of cool understatement in relation to comic mayhem is surprise and contrast . . . in establishing calm centres in the midst of slapstick hurricanes.’ Rosenbaum mentions Buster Keaton’s poker face in this context, but he might just as easily have cited Chaplain’s, Stan Laurel’s, Oliver Hardy’s, or a thousand others. In EO, our beloved donkey is the calm centre in relation to the surrounding mayhem and malevolence.

In the same piece, Rosenbaum inadvertently explains much about EO when he quotes animator Pete Burness’s comments, to wit, ‘In the American cartoon, death, human defeat, is never presented without being followed by resurrection, transfiguration.’ Just as Eo gets knocked down but gets up again and again, a cartoon character can be flattened by a steamroller but rise immediately, intact and full of life. ‘So’, Burness concludes, ‘it seems obvious that the American cartoon, rather than glorifying death, is a permanent illustration of the theme of rebirth.’ In European independent film culture, particularly in Central European culture something different and more honest more often happens; people and animals, cup your ears kids, die. Balthazar dies. Joan of Arc dies. No happy ending. The End. ‘Thank god there are so many different types of cinema,’ Skolimowski says, ‘If we didn’t have Hollywood productions, we probably wouldn’t appreciate artistic films and vice versa.’

What contribution might Skolimowski’s kinetic experimental film make to change? One cineoutsider reviewer recently grouped Glass Onion, The Menu and The Triangle of Sadness as three films, released last year, in which retributive justice is seen to be done and the undeserving rich get their comeuppance. Each of The Banshees of Inisherin, The Triangle of Sadness and EO contain harrowing scenes in which violence is done to donkeys. Are films featuring the guilty perpetrators and innocent victims of capitalist rapacity not two sides of the same coin? Might they not operate as metaphorical and satirical weathervanes? The status quo might have tightened its grip in recent years, but there are signs that a backlash against those who profit from cruelty to animals, from climate change and social collapse, is under way. Perhaps entitled nepo babies and greedy carnivores alike might soon be consigned to the dustbin of history. Be that as it may, we might as well add three recent documentaries on the lives and conditions of animals to our lists of films – to make a troika of trios: Stray (dogs), Gunda (pigs) and Cows (yep, cows).

Skolimowski is at pains to point out that EO was conceived long before those three films were made, but films like them and his own, which view the world, as it were, from below point to a significant shift in attitudes to other animals. Given that we are now ensconced in the sixth extinction epoch, given the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, perhaps people are beginning to value survivor species more. The rise in veganism and vegetarianism, once derided as faddish left-wing self-indulgence, suggests there is a growing recognition that what we eat and that how we treat other species has profound human consequences.

If that is so, I’d like Nicolas Geyrhalter’s forensic dissection of industrial food production, Our Daily Bread, which left us in no doubt about the depredations of the extractive economy, played its part in the advance. EO can only add to the number of sentient citizens who side with all exploited, maligned, marginalised, maltreated creatures - regardless of their species or race. Maybe it will soon become fashionable to turn, as the animals in Kornél Mundruczó's White God do, on those who rain cruelty down upon the powerless. Skolimowski and partner, co-producer and co-writer Ewa Piaskowska say they were 'trying to offer a voice to the voiceless, to those who couldn't speak for themselves,' which is, after all, what great art has always done. EO may or may not be harbinger of cinema's rebirth but this bold, brave, dazzling, fiery, feisty, original blaze of a film uses images and sound as teeth and lips to bite with - and few who see it will remained unmarked or unmoved.

|